A Little History

Society and Culture

The 1890s were both the final decade of the 19th century and the end of the Victorian era. Queen Victoria, who had reigned in England since 1837, died in January of 1901. Because her reign lasted for about 63.5 years, there were many people alive at this time who had never known life without Victoria as queen.

In America, this time, during the late 19th century, was also known as the Gilded Age (considered to range from about the 1870s to the early 1900s). When you gild something, you cover wood, stone, or a much cheaper metal with a thin layer of gold for decoration. To some people, this represented an era where apparent prosperity and economic growth for some layers of society covered up more serious problems of poverty and inequality beneath the surface. Much of the decade would actually be marked by economic depression. In 1899, newsboys in New York went on strike to protest changes to the cost of the newspapers they were selling. (This event was depicted in fictional form in the Disney movie Newsies in 1992.)

Sometimes, the 1890s is also called the Gay Nineties or Naughty Nineties (in the United Kingdom) because of some of the more daring forms of art and entertainment available, such as Oscar Wilde plays, and because of some of the social scandals that took place during the decade.

During this decade, there were 45 states in the United States. Oklahoma would be added in 1907. Arizona and New Mexico would remain territories until 1912, still growing out of their “Wild West” image.

Society was becoming more industrialized and urban. Populations had already started shifting from the countryside to the big cities, and factories were increasing production of consumer goods. New technological developments were changing people’s lives. Use of electric lights was increasing, although, particularly in rural areas, many were still using oil lamps. Other new technological developments were beginning to make daily life easier. Changes to the design of bicycles led to a sharp increase in the popularity of bicycling. Wilhelm Rontgen, a German physicist, discovered x-rays. There were also new developments in producing moving pictures, like the kinetoscope.

People were generally optimistic about the future and changes in their lives. “Progress” would be a good way to describe what many people were looking for and what they prided themselves on achieving. Society still had its problems, but life was improving in many ways, and people involved with social movements were pressing for further change. Some of the changes they wanted would still be a long time coming, there was a sense that society as well as technology could improve, that it was just a matter of time and effort. The “Progressives” were pushing for women’s suffrage, a minimum wage, and other labor laws, such as safety regulations and limits on child labor.

Childhood

For many, being a child during these years was difficult. Child labor, even for rather young children, was still legal in the United States and would remain legal, in some form, for many more years. Children growing up on family farms would naturally engage in farm chores, supervised by parents and older siblings, but as the country became more industrialized, children were increasingly used in factories. Children were also used in coal mining, which had its own dangers and health risks. Poor families and immigrants often relied on money that their children earned to help make ends meet, and industries profited from their cheap labor, which made it difficult to keep rules and limits in place for the children’s welfare.

The practice of sending homeless or parentless children on “Orphan Trains” (typically called “Baby Trains” or “Mercy Trains” at the time) from the big cities on the East Coast of the United States to live and work on farms in the Midwest (or even further west) began in the 1850s and continued until the 1920s. The theory was that living in the country and working on farms would be more wholesome for them than remaining in crowded cities. For many of them, it did work out, and they lived better lives that they would have had otherwise. However, some were simply exploited as a source of cheap labor.

Children from more affluent families were more likely to focus on education rather than working, although many did not pursue higher education. In those days, not many jobs required college degrees, and more people could get decent jobs with a high school education or less. (Back when I was studying journalism, my teacher explained that newspaper articles are traditionally written at about an 8th grade reading level (roughly age 13 or 14 in the United States), partly to make them accessible for different age groups and reading abilities and partly because, for a long time, that was about the standard education level of adults who could read.)

It was common for babies to be delivered at home rather than in a hospital, and in the case of families who lived in rural areas, it was more likely that the birth would be attended by family members or women from neighboring farms than by a physician. Infant mortality rates were higher during this period than in modern times because the level medical care available wasn’t as good, antibiotics like penicillin had not yet been developed so infectious diseases were more likely to turn deadly, and there were less vaccines for preventing diseases in the first place. It was fairly common for families to lose at least one child in infancy. This is also part of the reason why the overall life expectancy was lower.

It wasn’t that adults would always die at a much younger age (although that did happen sometimes because of diseases or accidents); it was also that quite a lot of people didn’t make it to adulthood, or even out of early childhood, in the first place. Remember that an “average lifespan” for a decade is an “average” number (the “mean” in math), not the most common number by itself (the “mode” in math). The difference is important because, to find out what age an adult would likely live to once they reached adulthood, you would have to focus on the average age at death only for those who reached adulthood, not including infants and children. Using the lifespan chart for England and Wales on the page I linked, predicted average lifespan at birth around this time was in the 40s, but predicted average lifespan for those who reached their 20s during the same period was in the 60s, which is a significant difference. Adding in the infant mortalities brings down the average overall and can give you a false picture that no one ever lived to see their grandchildren, which was not the case. So, if a person managed to survive some of the riskier points of life, such as early childhood or the child-bearing years for women, their odds of living to what we might consider a more normal lifespan might be better than you think. Of course, that’s “if.” People who lived at this time period would have been aware of the dangers of diseases and other risks for themselves and their children, and they would have known that even if they survived to adulthood, they might well lose a child someday. The good news is that, during the coming 20th century, new medicines and vaccines helped to save many lives that would otherwise have been lost, giving this generation’s grandchildren and great-grandchildren a far better chance in life than they had.

Literature

During this decade, Oscar Wilde published The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), Bram Stoker published Dracula (1897), and H. G. Wells published The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), and The War of the Worlds (1898).

In late 19th century Britain (also in areas with heavy British influence, including Canada, Australia, and sometimes the United States), many children’s stories were published in magazines that were printed every week or month. At the end of the year, shortly before Christmas, many children’s magazines would publish a collection of favorite stories, articles, pictures and games that had been published that year. These collections were called “annuals,” and they were often marketed as ideal Christmas presents for children. Later, during the early 20th century, the annuals also included some new stories that hadn’t been published yet. This practice continued up until World War II, when many of the annuals could not be printed because of paper rationing. Some of the annuals from the 1890s are:

- Blackie’s Children’s Annual – published in Scotland

- Nistor’s Holiday Annual – some pages contained moveable parts

- The Girls’ Own Annual – Printed from 1880 to 1940 and marketed to middle-class girls.

Children’s Fiction Books

General Fiction

Captain January (1891)

A lighthouse keeper adopts an infant girl after saving her from a shipwreck. For the first years of her life, the girl’s real identity is unknown, so the lighthouse keeper calls her “Star.” However, some of the townspeople begin to question the old lighthouse keeper’s fitness to take care of Star, and the girl’s real identity is discovered. By Laura E. Richards.

This book was later adapted as a silent movie in 1924 and a sound movie with Shirley Temple in 1936.

The Carved Lions (1895)

A sad story about a lonely girl at a harsh boarding school. By Mrs. Molesworth.

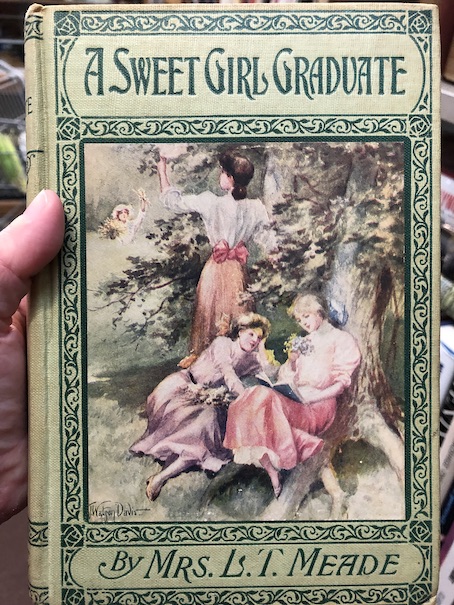

A Sweet Girl Graduate (1891)

A drama about a poor girl who attends a ladies’ college in England, confronting class differences and toxic friendships and the obsession some of her fellow students have with the memory of a popular student who died. Later editions were published under the title Priscilla’s Promise. By Mrs. L. T. Meade.

Series

Children’s book series from the 19th century about the Carr family, especially their daughter, Katy. 1872-1890.

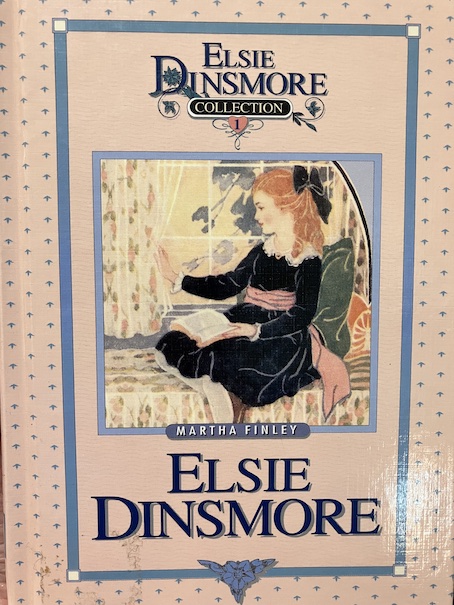

Elsie Dinsmore

A young girl struggles to become close to her widowed father after he returns from an extended trip in Europe. The stories emphasize Christian values. It was a highly popular series during the 19th century. By Martha Finley. 1867-1905.

The original stories take place in the American South before the Civil War and contain language and situations that would be inappropriate for modern children. The books have received criticism for being too preachy and for having an abusive father. However, revised editions of the books were published in the late 1990s, and there were Elsie Dinsmore dolls to go with the books. I’ve never read any of these, either the old or the new. I hadn’t even heard of them before I started researching children’s books from this period, although I later discovered some books for children and adults that reference this series, including some adult mystery books by Elizabeth Peters..

The Five Little Peppers Series

A widow and her five children do their best to support themselves, eventually finding a wealthy benefactor. By Margaret Sidney. 1881-1916.

The Little Colonel Series

A Southern colonel disowns his daughter for marrying a Yankee, but they later reconcile when the colonel meets his young granddaughter and recognizes her as a kindred spirit. By Annie Fellows Johnston. 1896-1914.

This is one of the series that I think demonstrates how much the Civil War and its aftermath were still on people’s minds. This was a very popular series in its time, and Shirley Temple starred in a movie version of the first book in the series in 1935. I’ve seen the movie but never read the books.

Mildred Keith

A tie-in series with the Elsie Dinsmore series. Mildred is a cousin of Elsie. The series emphasizes similar Christian themes. Mildred and her husband end up becoming abolitionists and support the union during the Civil War. This series was also revised and reissued during the early 2000s. By Martha Finley. 1876-1894.

The Three Margarets Series

Three cousins are all named “Margaret” after their grandmother. However, all three girls have grown up in different places and in different circumstances, they all have different personalities, and on the surface, they seem to have little in common other than their first name and the fact that they’re cousins. The Margaret who goes by Margaret is quiet and bookish. The Margaret who is called Peggy is brave but clumsy. The Margaret who is called Rita has a Cuban mother (they emphasize this in the story, and there are some stereotypes surrounding it) and has a fiery and dramatic personality. When the three Margarets are brought together by their uncle one summer so he can get to know them and they can get to know each other, they bond with each other, and it changes their lives. By Laura E. Richards. 1897-1904.

Humor

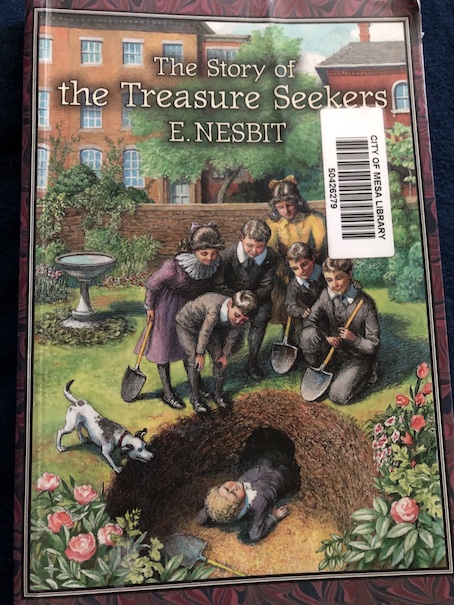

The Story of the Treasure Seekers (1899)

The Bastable children try various schemes to help their father when the family needs money. Part of the The Bastable Children Series. This book is public domain and available on Project Gutenberg. By E. Nesbit.

Adventure

Captains Courageous (1897)

A spoiled rich boy, Harvey, is rescued by a fisherman at sea after he’s washed overboard from the steamship he was traveling on. Nobody on board the fishing boat is impressed by the spoiled Harvey or believes him when he tries to explain how wealthy and important his family is and why they need to take him to port immediately. Instead, he gets his first taste of discipline and is immediately put to work until the fishing boat makes port again. Harvey’s adventures on the boat begin making a man out of the spoiled boy, and the friends he makes are rewarded for rescuing him. By Rudyard Kipling.

The Jungle Books (1894)

The book contains different stories about animals in India. The story about Mowgli, the human boy raised by wolves, was later made into a movie by Disney. By Rudyard Kipling.

Moonfleet (1898)

A story of smugglers and treasure. By J. Meade Falkner.

Series

The first of the Stratemeyer Syndicate series. Three brothers, Tom, Sam, and Dick Rover, have adventures and solve mysteries while attending a military boarding school. 1899-1926.

Fantasy

The Adventures of Mabel (1896-1897)

Mabel is a little girl who gains the ability to talk to animals and has adventures with fantastic creatures. By Rafford Pyke (Harry Thurston Peck).

The book is available online through Internet Archive.

The Book of Dragons (1899)

A collection of stories about different types of dragons. By E. Nesbit.

The Reluctant Dragon (1898)

The people of a village are terrified of a dragon, but a young boy becomes friends with it. By Kenneth Grahame.

Series

A series of collections of classic fairy tales. By Andrew Lang. 1889-1910.

Mystery

Series

Historical Fiction

Picture Books

A word of warning: I seriously debated about telling you about some of these, because of the racial aspects of books from this era, but they are historical, and it’s worth telling you where they fit into the general family of children’s literature. (Kind of like a relative with a somewhat checkered past, who everyone agrees was a cute kid but nobody really wants to talk about around the dinner table now.) Books from this era had a long-lasting impact on culture and children’s literature, both positive and negative. On the negative side, this is the era when the term “golliwog” was coined. If you don’t know what that is, I’ll define it for you, but understand that caricaturing people isn’t nice. If you wouldn’t want it done to you, you shouldn’t do it to others. I’m not an apologetic for this type of literature. It just is what it is. Fun in some ways, nostalgic for some, but not fun or really kind to everyone. The lack of kindness is the problem. I only explain so you’ll understand. You have been warned.

The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls and a Golliwogg (1895)

I don’t know if any company still makes golliwog toys anymore, but you can still occasionally find them in antique shops. Please, don’t make any yourself. Expect criticism if you do. Read on.

The plot of the book is pretty straight-forward. This story is told in rhyme, and it’s about a pair of wooden dolls and their adventures with other toys. They go outside on a winter’s day, and after having some fun and adventures, manage to get back to their toy shop before anyone realizes that they’ve been gone. Toys with lives and personalities of their own are classic themes in children’s literature, but what makes this story problematic is the introduction of the Golliwogg.

In the context of the story, the Golliwogg is actually a nice character, a toy who lives in a toy shop with other dolls, although the wild-eyed appearance is somewhat horrifying. For awhile, it was popular to make toys designed after him, and there were earlier dolls that looked like this, like the one that inspired the character. Basically, they’re rag dolls that look like blackface minstrels, typically with wide, staring eyes and thick red lips that look kind of like clown lips. In spite of its looks (or maybe even because of them?), this image became so popular that it was also used to market products, like candy. They were considered perfectly acceptable toys for children through the mid-20th century (possibly longer, in some places), and there are people who are still alive in the early 21st century who had them as children and feel nostalgic about them.

Around the time of the Civil Rights Movement, people started to question the appropriateness of these toys and the messages that they were sending to children, and they lost popularity. Today, many people who didn’t grow up with them find these toys and similar images offensive and upsetting. There are apparently some people who seriously collect these toys because of their nostalgic or historical value, including this man, but I do not recommend making new ones or giving them to children. It takes emotional maturity to understand the past, put it in perspective, and deal with it appropriately. Many people use dolls to help teach children how to treat smaller children or to act out their future lives. Teaching kids that it’s okay to look at people like they’re ugly jokes is not the wisest decision. Even if you don’t mean it as an insult, it’s better not to give the impression that you do. Think before you act. If you find one of the antique dolls, treat it with respect. No matter who you are, these toys are older than you, and they’ve been through quite a lot. The author of this book, Florence Kate Upton, said that she was upset by what her character turned into once it got out of her control.

This book is public domain and on Project Gutenberg. This book is actually a first in a series, and later, the famous children’s author Enid Blyton also wrote books with golliwogs, although hers weren’t as nice as the original character in this book.

The Comic Picture Book (1898)

A collection of funny stories about animals. By W. B. Conkey Company.

Little Black Sambo (1899)

I don’t want to do an actual post on the book, especially not one with pictures, but it’s worth a brief description to explain why. When people talk about racism in children’s books, this is a classic one to bring up.

The plot itself isn’t too bad although it’s a little surreal. The story takes place in India (apparently), and a boy named Sambo gets some snazzy new clothes. However, while he’s wearing them, he gets chased by tigers. To keep them from eating him, he offers them his nice new clothes. Tigers are apparently very vain, so they each grab a different article of clothing and put them on. Then, they start arguing over which of them looks the best, and they start chasing each other around and around in circles until they finally melt into butter (because, wherever this story takes place, tigers are apparently dairy-based). So, Sambo is able to get his clothes back, and he takes the butter home so that his mother can use it for pancakes. Seriously, that’s the plot.

So, why is this book a problem? It’s partly about where it takes place (Does “Little Black Sambo” really sound like a name from India to you? His parents, I kid you not, are named Black Mumbo and Black Jumbo. Yeah, I see what you did there.), but it’s also largely about the pictures. The pictures vary in style between different editions of the story, and ones that are drawn like realistic human beings who might actually live in India aren’t too bad. It’s the ones where the characters are designed to look like caricatures of black people (which make no sense for India and are pretty appalling), kind of like a golliwog, that are the problem. The Wikipedia page has some examples to show variations in the style.

I was born in the early 1980s, and I never actually saw a copy of this book as a child. It’s public domain now and available through Project Gutenberg (prepare yourself for horrible illustrations if you look). However, my mother described it to us once, telling us that there used to be a restaurant called Sambo’s which capitalized on the story by selling pancakes with “tiger butter.” I asked if there was anything special about “tiger butter”, like cinnamon stripes or something to make it tiger-like, but apparently not. As far as my mother remembers, it was just butter. This seems like a missed opportunity to me.

Some people who grew up around the mid-20th century or earlier may still have some fond memories of this story, probably associated with pancakes. I’ll admit that the idea of turning tigers into butter for pancakes is kind of cute. However, if you’re going to tell a story set in India, the people should look like people who might live in India, and if you’re going to sell something called “tiger butter”, it should have stripes, because otherwise, it’s just butter. Some people have attempted to save this story by producing editions with better drawings and different names for the characters.

Children’s Non-Fiction

Gladsome Hours: Lesson Book for Little People (1890)

Contains the alphabet, spelling words, and short stories for reading practice. Edited by Capt. Edric Vredenburg.

Children of the Decade

Children born in this decade in the United States:

Popular 1890s Names – Most would be names that we would consider “classics” in the early 21st century, like: Mary, Anna, Margaret, John, William, and James.

They were young around the time the Wright brothers built and flew their first airplanes during the early 1900s. Their earliest memories would be from a time before aviation existed.

All of them would have been alive during World War I (1914-1918) and would have remembered the event afterward. Those who were born in the first part of the decade would have been old enough to actually take part in the war, and possibly some born toward the end of the decade, if they joined in their teens. All of them would have called the war “The Great War” throughout their childhood because World War II had not yet occurred.

They were born before women in the United States could vote. None of their mothers had the right to vote at the time of their births or for their entire childhoods. They would later be adults when women’s suffrage was granted, and girls born in this decade may have been among the first women to vote in the United States after the ratification of the 19th Amendment (although some western states had women voting even before that).

They lived during a time when people not only did not have television but also did not have home radios (which were invented and popularized in the 1920s). If you wanted music at home, you had to either learn to sing or play an instrument yourself, listen to a family member who could, or use a phonograph (early record player) to play a record. Phonographs commonly were of the wind-up variety, so no electricity was needed. They were adults by the time home radios were invented.

They would have been in their 20s and 30s during the 1920s and Prohibition. Some of them were flappers (or Bright Young Things) during that period or frequented speakeasies, although that would largely depend on their individual personalities. People who were more daring, had more of a desire to be “modern,” or had less concern for rules and laws (especially those who enjoyed pushing the limits of society) would be more likely to engage in these activities. People who were more shy or more conservative in their habits and those who truly believed in the cause of Prohibition would not have gone to speakeasies and would have been less daring in their clothes and personal habits. A good number of people would have also fallen between these groups in their habits, more modern and maybe a little daring in some ways but not in others. (For example, wearing some of the latest fashions but not the more daring ones and sneaking an occasional drink quietly at home, which was possible for those who still had alcohol at home from before Prohibition began or those who knew how to make their own, but not going to speakeasies.) There are variations in human behavior in every period of history.

They would have been in their 30s and 40s during the Great Depression. By then, many of them would be married with children of their own and could have been among those who lost their jobs or were struggling to find work while still providing for their families. Their children’s lives may have been marked by poverty, uncertainty, and movement from place to place as their parents searched for work.

They would later have been in their 40s or 50s during World War II. Some of them may have sent their sons overseas to fight. These people were parents of the “Greatest Generation.”

They would have been middle-aged or older adults at the beginning of the Cold War and witnessed the beginning of the technology race and the invention of space flight. Most of them would not have lived to see the end of the Cold War, which happened when they would have been in their 90s, almost 100 years old for those born early in the decade.

They would have been in their 60s and 70s as the Civil Rights Movement took place. When they were children, schools were segregated by race. Their children’s schools would also have been segregated. Their grandchildren would likely have been among the first to attend desegregated schools.

They would have to have lived to be at least in their 90s in order to have witnessed the time people gained the ability to access the Internet and send and receive e-mail from home computers.

Children born in this decade would also have read books from the following decade, the 1900s, in their youth. However, children who were old enough to read some of the books published in the early part of this decade when they were first sold would have been born in the preceding decade, the 1880s.

Children’s Authors Were Children, Too!

Everyone was young once, and I’d just like to take this opportunity to remind readers that authors born around this time would have grown up like other children of their time, witnessing the same events and reading the same books as they grew up.

Children’s authors born in this decade:

Esther Forbes – June 27, 1891 – Author of Johnny Tremain (1943)

J.R.R. Tolkien – January 3, 1892 – Author of the Lord of the Rings books (1937-1955)

Maud Hart Lovelace – April 25, 1892 – Author of the Betsy-Tacy books (1940-1955)

Robert Lawson – October 4, 1892 – Author of Ben and Me (1939) and Rabbit Hill (1944)

Lucy M. Boston – December 10, 1982 – Author of the Green Knowe fantasy books (1954-1976).

Richard and Florence Atwater – December 29, 1892 and September 13, 1896, respectively – Co-authors of Mr. Popper’s Penguins (1938)

Alice Dalgliesh – October 7, 1893 – Author of The Courage of Sarah Noble (1954)

Lois Lenski – October 14, 1893 – Author of Strawberry Girl (1945)

James Thurber – December 8, 1894 – Author of books and stories for children and adults, my favorite of his children’s books is The 13 Clocks (1950)

Laura Bannon – 1895 – Author and illustrator of Patty Paints a Picture (1946) and Katy Comes Next (1959)

Carol Ryrie Brink – December 28, 1895 – Author of Caddie Woodlawn (1935) and Two Are Better Than One (1968)

Betty Smith – December 15, 1896 – Author of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1943)

Enid Blyton – August 11, 1897 – Author of The Famous Five series (1942-1963) and many other children’s books

Ludwig Bemelmans – April 27, 1898 – Author of the Madeline series (starting in 1939)

Scott O’Dell – May 23, 1898 – Author of Island of the Blue Dolphins (1960) and Sing Down the Moon (1970)

H.A. Rey – September 17, 1898 – Co-creator of the Curious George series (1941-1966)

C. S. Lewis – 29 November 1898 – Author of the Chronicles of Narnia (1950-1956)

Claire Huchet Bishop – December 30, 1898 – Author of The Five Chinese Brothers (1938) and Twenty and Ten (1952)

Erich Kästner – February 23, 1899 – Author of Lisa and Lottie (1949) and Emil and the Detectives (1929)

E.B. White – July 11, 1899 – Author of Stuart Little (1945) and Charlotte’s Web (1952)

P. L. Travers – August 9, 1899 – Author of the Mary Poppins series (1934-1988)

Jean de Brunhoff – December 9, 1899 – Author and illustrator of the Babar series

Other Resources

Documentary Films

CrashCourse

CrashCourse is a YouTube channel with fun educational videos on a variety of topics and different periods of history. The videos are fairly short for educational lectures. Most are less than 15 minutes long. These videos are intended for teenagers and older, so be aware that there may be topics and language inappropriate for younger children.

- Imperialism: Crash Course World History #35

- Expansion and Resistance: Crash Course European History #28 – Discusses the Opium wars and includes an explanation of the racial attitudes that evolved to justify imperialism and colonization.

- American Imperialism: Crash Course US History #28

- Gilded Age Politics:Crash Course US History #26

- Growth, Cities, and Immigration: Crash Course US History #25

This Mysterious Event Led to the Spanish-American War

The sinking of the Maine.

THE ULTIMATE FASHION HISTORY: The 1870s – 1890s

An educational lecture about clothing in the late 19th century. Discusses the introduction of the bustle, which replaced the hoop skirt in women’s fashions, and leg-of-mutton sleeves. About 20 minutes long.

For more about 1890s culture:

The People History: 1890 to 1899 Important News, Key Events, Significant Technology

Lists of 1890s children’s books:

19th C. Classic Children’s Books You Might Have Overlooked

A table of authors of 19th century girls’ series books and their works. The books range across the 19th century.