A Little History

Major Events and Culture

The 1860s were part of the Victorian era. Queen Victoria, who had reigned in England since 1837, died in January of 1901. Her reign would last for about 63.5 years.

In the United States, this was the decade of the Civil War (1861-1865). The American Civil War was the bloodiest war in the history of the United States and left permanent marks on American society and culture. One of the results of this war was that slavery was made illegal in the United States. Even after slavery was abolished, black people in the United States didn’t have the same rights as white people or equal treatment for many years. It wasn’t until about 100 years later, during the Civil Rights Movement, that real progress was made in eliminating segregation and securing civil rights for minorities. President Abraham Lincoln was shot by an assassin at Ford’s Theater in 1865, as the war came to a close. It was the first time that a US President was assassinated.

One of the more unusual side effects of the Civil War was the rise in spiritualism in the United States. Spiritualism already existed as a movement, but many people had lost friends, relatives, and loved ones in the war, and some of them became obsessed with the afterlife and communicating with the dead. Mary Todd Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln’s wife, was one of the people who believed in spiritualism, having lost her young sons to disease and, later, her husband to assassination.

Meanwhile, society was becoming more industrialized and urban. Populations had already started shifting from the countryside to the big cities, and factories were increasing production of consumer goods. New technological developments were changing people’s lives. At the end of the decade, 1869, the United States’ First Transcontinental Railroad was completed, linking the East Coat to the West Coast and making travel across the country faster and more comfortable.

Children

For many, being a child during these years was difficult. Child labor, even for rather young children, was still legal in the United States and would remain legal, in some form, for many more years. Children growing up on family farms would naturally engage in farm chores, supervised by parents and older siblings, but as the country became more industrialized, children were increasingly used in factories. Children were also used in coal mining, which had its own dangers and health risks. Poor families and immigrants often relied on money that their children earned to help make ends meet, and industries profited from their cheap labor, which made it difficult to keep rules and limits in place for the children’s welfare.

The practice of sending homeless or parentless children on “Orphan Trains” (typically called “Baby Trains” or “Mercy Trains” at the time) from the big cities on the East Coast of the United States to live and work on farms in the Midwest (or even further west) began in the 1850s and continued until the 1920s. The theory was that living in the country and working on farms would be more wholesome for them than remaining in crowded cities. For many of them, it did work out, and they lived better lives that they would have had otherwise. However, some were simply exploited as a source of cheap labor.

Children from more affluent families were more likely to focus on education rather than working, although many did not pursue higher education. In those days, not many jobs required college degrees, and more people could get decent jobs with a high school education or less. (Back when I was studying journalism, my teacher explained that newspaper articles are traditionally written at about an 8th grade reading level (roughly age 13 or 14 in the United States), partly to make them accessible for different age groups and reading abilities and partly because, for a long time, that was about the standard education level of adults who could read.)

It was common for babies to be delivered at home rather than in a hospital, and in the case of families who lived in rural areas, it was more likely that the birth would be attended by family members or women from neighboring farms than by a physician. Infant mortality rates were higher during this period than in modern times because the level medical care available wasn’t as good, antibiotics like penicillin had not yet been developed so infectious diseases were more likely to turn deadly, and there were less vaccines for preventing diseases in the first place. It was fairly common for families to lose at least one child in infancy. This is also part of the reason why the overall life expectancy was lower. It wasn’t that adults would always die at a much younger age (although that did happen sometimes because of diseases or accidents); it was also that quite a lot of people didn’t make it to adulthood, or even out of early childhood, in the first place. Remember that an “average lifespan” for a decade is an “average” number (the “mean” in math), not the most common number by itself (the “mode” in math). The difference is important because, to find out what age an adult would likely live to once they reached adulthood, you would have to focus on the average age at death only for those who reached adulthood, not including infants and children. Adding in the infant mortalities brings down the average overall and can give you a false picture that no one ever lived to see their grandchildren, which was not the case. So, if a person managed to survive some of the riskier points of life, such as early childhood or the child-bearing years for women, their odds of living to what we might consider a more normal lifespan might be better than you think. Of course, that’s “if.” People who lived at this time period would have been aware of the dangers of diseases and other risks for themselves and their children, and they would have known that even if they survived to adulthood, they might well lose a child someday. The good news is that, during the coming 20th century, new medicines and vaccines helped to save many lives that would otherwise have been lost, giving this generation’s grandchildren and great-grandchildren a far better chance in life than they had.

Literature

In literature, this decade saw the publication of:

- Les Miserables (1862) by Victor Hugo

- Hereward the Wake (1866) by Charles Kingsley – A famous historical novel about the son of Lady Godiva.

- War and Peace (1869) by Leo Tolstoy

- Lorna Doone (1869) by Richard Doddridge Blackmore – A romance novel set in 17th century England.

- Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne (serialized before being published as a novel in 1870)

In children’s literature, Lewis Carroll published Alice in Wonderland, and Louisa May Alcott published Little Women. These two children’s books are classics known around the world.

Children’s Fiction Books

General Fiction

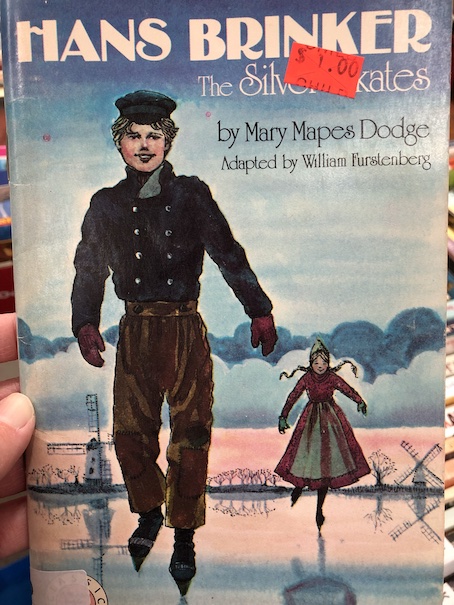

Hans Brinker, or The Silver Skates (1865)

Fifteen-year-old Hans and his younger sister Gretel dream of skating in an ice-skating race where the prize is a pair of silver skates. However, their father is injured and in desperate need of an operation. There is no money for them to afford the skates they will need to participate in the race until a doctor’s kindness changes things for their family. By Mary Mapes Dodge.

Little Women (1868)

During the American Civil War, the four March sisters grow up and discover their destinies. The first of a series. By Louisa May Alcott.

An Old-Fashioned Girl (1969)

Polly, a girl from the country, visits a friend who belongs to a wealthy family in the city. She is unaccustomed to the fancy clothes and habits of city life and feels out of place. However, when the family faces hard times, Polly reminds them of the things that are really important in life. By Louisa May Alcott.

Series

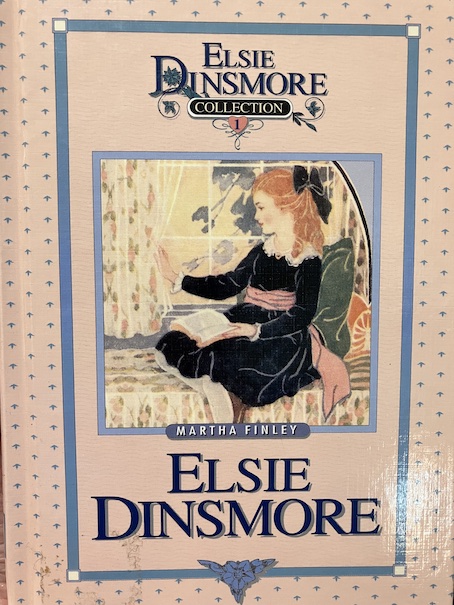

Elsie Dinsmore

A young girl struggles to become close to her widowed father after he returns from an extended trip in Europe. The stories emphasize Christian values. It was a highly popular series during the 19th century. By Martha Finley. 1867-1905.

The original stories take place in the American South before the Civil War and contain language and situations that would be inappropriate for modern children. The books have received criticism for being too preachy and for having an abusive father. However, revised editions of the books were published in the late 1990s, and there were Elsie Dinsmore dolls to go with the books. I’ve never read any of these, either the old or the new. I hadn’t even heard of them before I started researching children’s books from this period, although I later discovered some books for children and adults that reference this series, including some adult mystery books by Elizabeth Peters..

An unusual series from this time period featuring a young black character, a fourteen-year-old boy who is kind and intelligent, finding employment and dealing with racism in the Northern states before the beginning of the American Civil War. Rainbow is the nickname of the black character (they never call him anything else although he does apparently have another name), and Lucky is the name of a horse that he tames because he is good with animals. The series ends happily for Rainbow with a bright future and possible marriage ahead for him, in spite of the racism that he encounters. By Rev. Jacob Abbott. 1859-1860.

This five-book series is notable not only for its empathy with a black main character and open acknowledgement of racism but for its general understanding of human psychology as the author includes realistic human flaws in his characters and makes a point of explaining the reasons behind his characters’ behavior. The author also explains many small details of daily life in the mid-19th century. A number of character names are puns on their professions or natures, which is also fun. (“Rainbow” is also a pun nickname because he is “colored,” which was considered a more polite racial term at the time the stories were written. The characters actually talk about racial terms and make distinctions between what’s considered polite and what isn’t by mid-19th century standards during the course of the books in order to teach young readers how to speak politely.)

You can read all five books in this series online at Nineteenth-Century American Children & What They Read. This site also has commentary about each of the books in the series.

Adventure

The Gorilla Hunters: A Tale of the Wilds of Africa (1861)

A sequel to The Coral Island (1858). The characters from the first book go to Africa to hunt a gorilla. They also hunt a lot of other animals and stop some slave traders. By R. M. Ballantyne.

Fantasy

Alice in Wonderland (1865)

A young girl falls down a rabbit hole and finds herself in a strange land where nothing works like it’s supposed to. By Lewis Carroll.

The Golden Key (1867)

Two children find a golden key at the end of the rainbow and go on a journey to find the keyhole for the magical key, which will open the way to a magical land. By George MacDonald

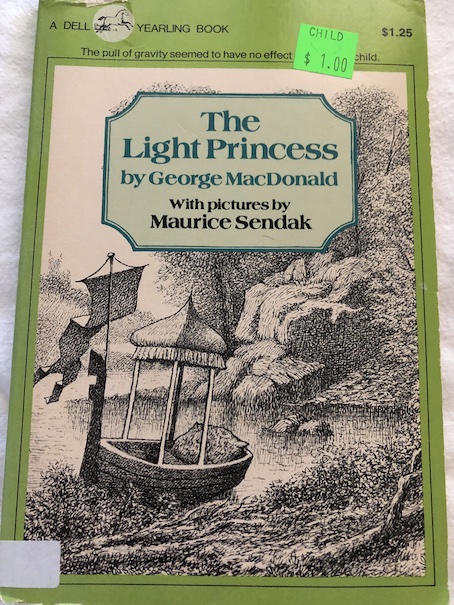

The Light Princess (1864)

From birth, a young princess is literally incapable of keeping her own feet on the ground. If people didn’t help her and keep her tied down, she would simply float away! Is there any way to cure her of her lack of gravity? By George MacDonald.

The Magic Fish-bone (1867)

A fairy gives Princess Alicia a magic fish-bone that will grant her wish, but only if she makes her wish at the right time. But, when is the right time, or is there one? By Charles Dickens.

The Water-Babies (1863)

A kind of dark, moralistic fairy tale, people who are drowned become “water-babies” but can earn a second chance at life by performing good deeds. (It’s partly a satire against child labor, but I’m not going to read it. I hate dark stories like this, and it’s also known for insulting various groups of people like Americans (the book is British), Jews, Catholics, blacks, and poor people. Whatever the author’s problems are, I don’t want them to be mine. This book was referenced by the characters in Mother Carey’s Chickens.) By Charles Kingsley.

Picture Books

Children’s Non-Fiction

Series

Children of the Decade

Children born in this decade in the United States:

Popular 1860s Names – Most would be names that we would consider “classics” in the early 21st century, like: Mary, Ann, Elizabeth, John, William, and Charles.

They would have been born around the time of the American Civil War (1861-1865). The ones born in the early part of the decade would have been babies and small children during the war and, later, wouldn’t remember aspects of life before the war began. Those born after the war would never know a time when slavery was legal in the United States, although they would have heard about it from their parents and other elders.

They would have been in their 30s or 40s around the time the Wright brothers built and flew their first airplanes during the early 1900s. Their earliest memories would be from a time before aviation existed.

They would have been in their 40s through their 50s during World War I (1914-1918). Some of their children may have take part in the war. All of them would have called the war “The Great War” before World War II.

They were born before women in the United States could vote. None of their mothers had the right to vote at the time of their births or for their entire childhoods. They would later be adults in their 50s and 60s when women’s suffrage was granted after the ratification of the 19th Amendment (although some western states did have women voting even before that).

They lived during a time when people not only did not have television but also did not have home radios (which were invented and popularized in the 1920s). If you wanted music at home, you had to either learn to sing or play an instrument yourself, listen to a family member who could, or use a phonograph (early record player) to play a record. Phonographs, developed in 1877 by Thomas Edison, commonly were of the wind-up variety, so no electricity was needed. They were older adults by the time home radios were invented.

They would have been in their 60s and 70s during the Great Depression, although not all born in this decade would have lived to see this period of history. By then, many of them would have been grandparents, and some may have even been great-grandparents. Their children or grandchildren could have been among those who lost their jobs or were struggling to find work while still providing for their families.

Not all of them would have lived to see World War II. Those who did would have been in their 70s or 80s. Fewer of them would have lived to see the start of the Cold War at the end of World War II. Almost none would have lived to see the Civil Rights Movement, which started around the time they were in their 90s, ending when they were about 100 years old.

Children born in this decade would also have read books from the following decade, the 1870s, in their youth. However, children who were old enough to read some of the books published in the early part of this decade when they were first sold would have been born in the preceding decade, the 1850s.

Children’s Authors Were Children, Too!

Everyone was young once, and I’d just like to take this opportunity to remind readers that authors born around this time would have grown up like other children of their time, witnessing the same events and reading the same books as they grew up.

Children’s authors born in this decade:

J.M. Barrie – May 9, 1860 – Creator of the character of Peter Pan

Alice Turner Curtis – September 6, 1860 – Author of several series for girls, particular ones that focus on American history

Edward Stratemeyer – October 4, 1862 – Founder of the Stratemeyer Syndicate, which created many famous children’s book series

Rudyard Kipling – December 30, 1865 – Author of The Jungle Books (1894)

Beatrix Potter – July 28, 1866 – Author of The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902)

Laura Ingalls Wilder – February 7, 1867 – Author of the Little House on the Prairie series (1932-1953)

Other Resources

Documentary Films

CrashCourse

CrashCourse is a YouTube channel with fun educational videos on a variety of topics and different periods of history. The videos are fairly short for educational lectures. Most are less than 15 minutes long. These videos are intended for teenagers and older, so be aware that there may be topics and language inappropriate for younger children.

- Imperialism: Crash Course World History #35

- Expansion and Resistance: Crash Course European History #28 – Discusses the Opium wars and includes an explanation of the racial attitudes that evolved to justify imperialism and colonization.

- The Railroad Journey and the Industrial Revolution: Crash Course World History 214

- The Election of 1860 & the Road to Disunion: Crash Course US History #18

- Battles of the Civil War: Crash Course US History #19

- The Civil War, Part I: Crash Course US History #20

- The Civil War Part 2: Crash Course US History #21

- Reconstruction and 1876: Crash Course US History #22

- Gilded Age Politics:Crash Course US History #26

The Civil War Rages | America: The Story of Us (S1, E5)

From the History Channel. About 44 minutes long.

The Transcontinental Railroad Unites | America: The Story of Us (S1, E6)

From the History Channel. About 44 minutes long.

THE ULTIMATE FASHION HISTORY: The 1850s & 1860s

An educational lecture about fashions in the 1850s and 1860s. Contains some information and images not suitable for children! Fashions of the time were inspired by imperialism and also functioned to obscure women’s bodies and keep men at a physical distance with hoop skirts. About 14 minutes long.

For more about 1860s culture:

The People History: 1860 to 1869 Important News, Key Events, Significant Technology

Lists of 1860s children’s books:

Nineteenth-Century American Children & What They Read

Explains about the lives of children in the 19th century and books and magazines that they read. The focus seems to be on the 1870s and earlier.