The American Boy’s Handy Book by Daniel Beard, 1882.

This is a Victorian activity book for boys, focusing particularly on outdoor seasonal activities. It was not the first book of its kind during the Victorian era, but the author explains in the preface that he wanted to create a book of sports, games, and activities that would be better than the ones that he knew from his own youth, with instructions that were well-written, complete, and easy to follow, particularly written for American boys, without some of the foreign phrases found in other books or tips that would be impossible for them to use, like recommendations for shops in London that sell equipment for the various activities and pastimes.

The book is now public domain and available to read for free online through Internet Archive.

Historical Background

Daniel Beard wasn’t just an author who had an interest in providing useful guides to fun activities for American boys; he was also a social reformer who was one of the founding members of the Boy Scouts of America. Before the Boy Scouts of America was founded in 1910, there were other, smaller scouting organizations throughout the United States, and Daniel Beard had founded one of these groups in 1905, which he called the Sons of Daniel Boone. This group later went through a couple of name changes before Beard joined the Boy Scouts of America and merged his group with theirs.

The Beard family in general believed in the benefits of exercise, appreciation of the natural world, and healthy outdoor activities for youth people, both male and female. Daniel’s sisters, Lina and Adelia, would later be founding members of the Camp Fire Girls, the first major scouting organization for girls in America, during the 1910s, a cause which Beard also supported. (Camp Fire Girls was founded before the founding of the Girl Scouts. It had the opportunity to merge with the Girl Scouts at one point but didn’t. Today, it is now a co-ed scouting organization simply called Camp Fire.) A few years after the publication of The American Boy’s Handy Book, Lina and Adelia published their own book of activities specifically for American girls called The American Girl’s Handy Book, which had somewhat of an outdoor focus but not as much as The American Boy’s Handy Book or some of the other books that they would later write. These were not the only books that the Beards published, and they would later go on to write more books about activities and wilderness skills for boys and girls.

Contents of the Book

The activities in this book are organized by season, which makes sense because of the largely outdoor focus of the activities. Within each section, there are more specialized sections, focusing on particular pastimes in each season. The American Girl’s Handy Book follows the same seasonal organization, but The American Boy’s Handy Book doesn’t mention holidays as much as The American Girl’s Handy Book. There is only one holiday section in this entire book, and the holiday is the Fourth of July. Later editions of the book also have some extra notes and projects in the back.

My copy of the book has a foreword written in modern times, part of which notes that some of the activities in the book are not really recommended for modern children because they are not suitable for kids living in urban or suburban environments and because some of them are outright dangerous and involve fire. At least, children should not attempt these activities without close supervision and help. Some 19th century people managed to play with fire and not hurt themselves, partly because more of them lived in the countryside, away from houses that could be set on fire, and like the author of this book, also lived in places in the Midwest and East Coast that see a lot of rain, keeping plants and fields from drying out and becoming more flammable, and could also be near lakes, ponds, and rivers. However, not everyone lives in those types of places these days. (If you want an indication of what could possibly go wrong with trying some of the more flammable activities in the book, consider what’s happened with some of the more flammable or explosive gender reveal parties in modern times. Consider your environment before deciding whether these activities are feasible.) Also, not everyone from the 19th century or 20th century pulled off these activities unscathed, and it’s the ones who did get hurt or caused serious damage that make the concern. The writer of the foreword describes how a 19th century boy lost a leg attempting the fire balloon activity with his friends years before this book was published. (The fire got out of control, and his leg was badly burned when he tried to put the fire out.) That being said, there are many interesting activities in this book that are perfectly harmless and fire-free and that kids from any era can try, even those who don’t live in the countryside.

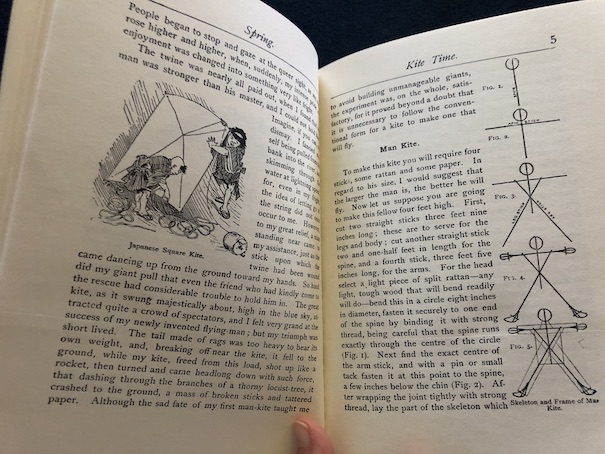

Spring

The spring section is mainly about making and flying kites and going fishing. The kites section explains how to make different types of kites in different shapes, like people, frogs, butterflies, fish, turtles, and dragons. One of these designs, called The Moving Star, involves attaching a lit lantern to the tail of a long kite. This kite is meant to be flown at night, so the light will bob in the air. It’s an interesting concept, although the instructions mention that certain types of lanterns are likely to just set fire to the kite. (I think I know how the author knows this.) The book provides instructions for making a custom lantern that will work better. This custom lantern featured a candle that is stuck between nails that are supposed to hold it in place, and it is supposed to be covered with red tissue paper (which is also sure to catch fire if that candle gets loose and falls over while it’s flying around). I’ll admit that the effect is probably neat, if you can pull it off without setting fire to something, but setting something on fire seems to be a likely outcome. This is one of the activities which wouldn’t work well for modern kids, especially if they live in places with highly flammable brush or dead grass and weeds or in the middle of areas with a lot of houses or apartments that would be set on fire if the flying lantern gets out of control (which is, apparently, a distinct possibility). Of course, thanks to modern technology, a battery-operated light could be an option.

There is also a section about war kites, which can be used for kite fighting.

The rest of the spring section is about different methods of fishing, how to make fishing tackle, and how to keep aquariums.

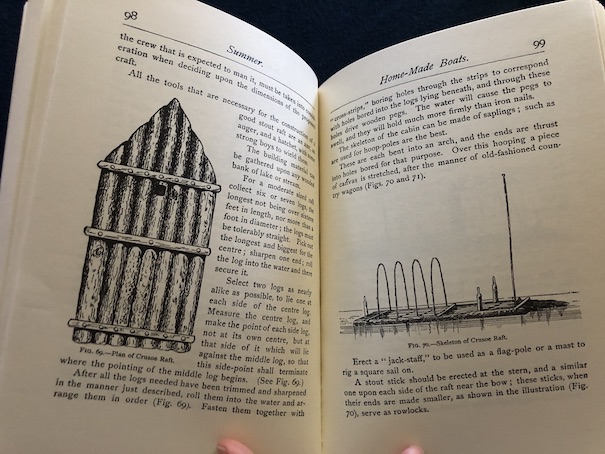

Summer

The summer section has more variety, although many of the activities are ones that modern boys can’t do if they live in an urban or suburban environment. There is more information about fishing in this section and how to make and sail different types of boats. I thought that the water telescope, which can be used to look at things under water, was really interesting. The book provides two sets of instructions for making a water telescope, one wooden and one metal.

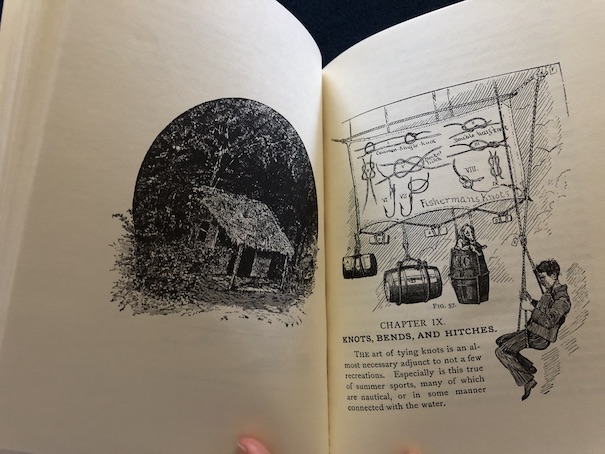

There is also information about different types of knots and how to tie them, blowing soap bubbles with a clay bubble pipe, and how to camp outside without a tent. The section about soap bubbles mentions “an aged negro down in Kentucky” whom the author knew as a child called “Old Uncle Cassius.” Uncle Cassius used to smoke a corn cob pipe, and he liked to amuse the children by blowing soap bubbles. The reason why the author brings up the subject of Uncle Cassius is that he had a particular trick where he would blow smoke-filled bubbles by filling his mouth from smoke from his own pipe before blowing some through the bubble pipe. The term “negro” is a bit archaic now, and I wouldn’t recommend smoking in general, but the author’s memories of Uncle Cassius seem to be fond ones, which is nice. The book doesn’t say whether or not Cassius was a slave, but the author was born in 1850, so my guess is that Cassius was either a slave or had been one earlier in life.

The section about soap bubbles also describes how children can use the gas from the gas lighting in their homes to blow bubbles, another activity that modern children can’t do.

As I mentioned before, fire is important to certain activities in this book. For Fourth of July, there are instructions for making a special kind of balloon that rises with heat produced by fire. They’re sort of like sky lanterns, made of paper. However, instead of having a place to set a small candle, these balloons have a “wick-ball”, which is a ball of rolled-up wick string, the kind used in an oil lamp, which is then soaked with alcohol and set on fire. The author notes that other people who make this type of balloon use small sponges instead, but he doesn’t think they’re as good because they don’t burn long, and as they burn out, the balloon comes back down, near where it started. He prefers to make a wick-ball so that it will continue burning and float out of sight. (I can’t help but notice that the sponge balloons, not burning for long and coming down nearby would also probably be easier to control and monitor for fire risk than the wick-ball balloons, which will float off to God-only-knows-where and get caught on who-knows-what before fully burning out.) The author says that he used to experiment with these as a child and has notes about which shapes are unsafe. Generally, it’s best to make them large and round, without a long neck at the opening. (As I said, the modern foreword in my copy notes that these types of balloons are actually dangerous and that kids have been injured trying to use them. This is why you don’t tend to see this type of activity suggested in modern children’s hobby books. Try it only at your own risk and remember that you’re responsible for any fires you start in the process. If you live in an urban setting or an area with a high risk of wildfires, don’t do it at all.)

There is quite a lot of information about activities involving real birds, like collecting bird nests and raising wild birds. (The modern view is that wild animals should be left wild and not kept as pets.)

There are also instructions for different types of hunting and how to make hunting weapons, including blow guns. In Meet Samantha from the Samantha, An American Girl series, she mentions that she read the instructions for how to make a boomerang in The American Boy’s Handy Book and that she wants to make and sell boomerangs to raise money to buy a new doll until her grandmother talks her out of it because that isn’t a proper activity for young girls. This is the part of the book where the boomerang instructions are, p. 190. Meet Samantha doesn’t say why Samantha was reading The American Boy’s Handy Book instead of The American Girl’s Handy Book in 1904, but that passage is mainly there to show the difference between what were considered acceptable activities for girls vs. acceptable activities for boys.

Autumn

The autumn section is much shorter than the previous two sections. It has information about trapping animals and practicing taxidermy. There is also a section about how to keep and train a pet dog. (Remember, that’s a commitment for life, not just for autumn.)

The part that I liked the best was the section about how to be a “decorative artist.” It teaches boys about photographic paper, how to make shadow pictures, and how to enlarge and reduce images.

Winter

The winter section has both indoor and outdoor activities, and the outdoor activities are designed for places with snow. (The author was born in the Midwest and lived on the East Coast of the United States, so these are the environments he considers for his outdoor activities.) He describes snowball fights, snow forts and houses, snow statuary, different types of sleds and sleighs, snow-shoes, and how to fish in winter.

For the indoor activities, there are instructions for making puppets and a script for a puppet show version of Puss-in-Boots. There are also tips for making costumes for people, so children could perform their own theatricals.

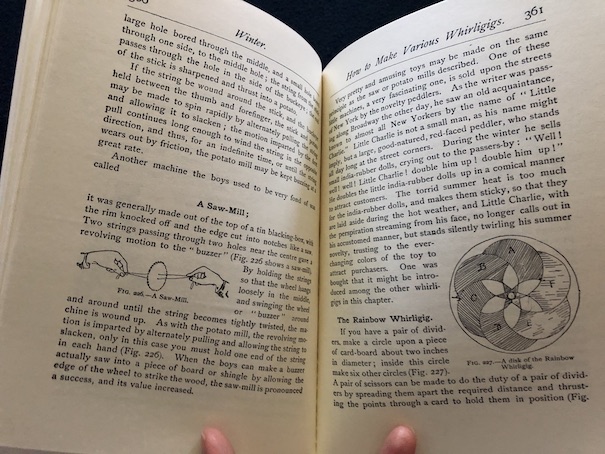

I particularly liked the sections about how to make and use magic lanterns and how to make different types of whirligig toys. The magic lantern was a kind of early slide projector. The whirligigs were homemade toys that would spin.

3 thoughts on “The American Boy’s Handy Book”