Gone-Away Lake by Elizabeth Enright, 1957.

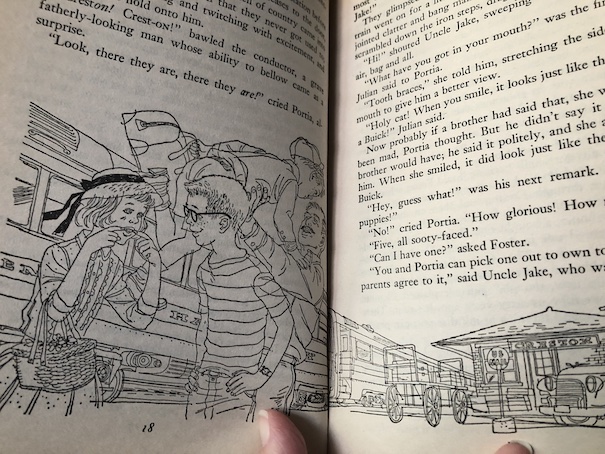

Eleven-year-old Portia and her six-year-old brother Foster are traveling alone by train to visit their aunt and uncle and twelve-year-old cousin Julian in the country for the summer while their parents are on a trip. Portia likes spending time with Julian because Julian is an amateur naturalist and tells her things about animals and birds. When Portia and Foster arrive, their aunt, uncle, and cousin tell them that their dog has had puppies. Portia is allowed to name them, and if her parents agree, she and Foster will even be able to keep one!

While Portia is out exploring the countryside with Julian one day, they find some garnets in a rock. They start chipping some out to take to Julian’s mother, and they find a carved inscription in Latin on the rock with the date July 15, 1891. They’re not sure what the Latin words mean. They figure out that part of the inscription refers to the Philosopher’s Stone, which was supposed to turn different substances to gold. Portia asks if this stone could be the real Philosopher’s Stone, but Julian says that’s impossible because they’ve been using knives to pry out the garnets, and they haven’t turned to gold. They continue to wonder what the inscription really means and why someone put it there.

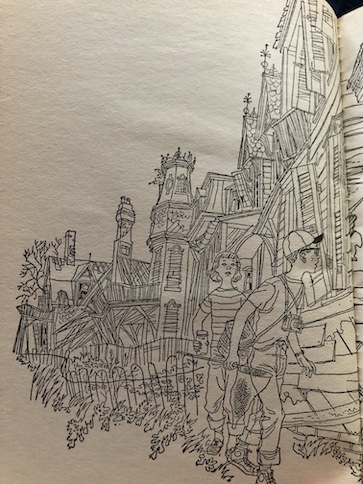

They explore the countryside further, getting lost. They aren’t too worried because they don’t need to be back soon. They follow a brook and find themselves in a swampy area. Strangely, they stumble over an old rowboat. Then, they spot a row of old, abandoned houses. The houses are in bad condition, but the kids can see that they were built in elaborate Victorian styles. The children wonder why those houses are there on the edge of swamp. Portia finds it a little creepy, but Julian wants to get a better look.

Then, the children hear a voice. Strangely, the voice is repeating an advertisement for medicine for indigestion. The children think it’s funny because no ghost would say something like that. Taking a closer look at the houses, they notice that one seems to be in better condition than the others that it has animals and a garden, so someone must be living there. Thinking about it more, Julian says that the swamp was probably once a pond or a lake, and that’s why it had houses and a rowboat. He hasn’t heard of a lake in the area, but he and his parents haven’t lived in the area for long. The children wonder who lives in the house and decide to find out.

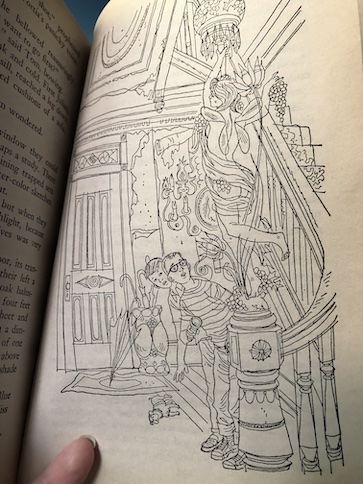

They find an old woman in old-fashioned clothing, listening to a radio. The old lady is surprised to see them but welcomes them, saying that it’s been a long time since she has seen children. She invites them to come inside her house, and the children find themselves in a cluttered and chaotic parlor with each wall covered in a different kind of wall paper. The woman introduces herself as Minehaha Cheever.

The children explain how they ended up there by coming through the swamp, and Mrs. Cheever says that they shouldn’t go through the swamp because there is a dangerous sinkhole there that they call the Gulper. She says that when it’s time for the children to go home, she’ll have her brother show them a better and safer way. Mrs. Cheever says that there used to be a lake there, and that her family and about a dozen others had summer houses there, but the lake largely dried up when a new dam was built. After that, the summer houses were abandoned, and many of them were vandalized. However, her father and another woman locked up their houses with the furniture inside, thinking that they would come back and move them, but they never did. The large and fancy old Villa Caprice is still untouched, but Mrs. Cheever says that she supposes that much of the contents is probably deteriorated. She says that the Villa Caprice gives her the creeps.

The children ask Mrs. Cheever why she’s there, and she says that she used to live somewhere else. After her husband died, she didn’t have much money, and she remembered that the house at the former lake was still there. Her brother, Pindar, also wanted to retire somewhere quiet, so they decided to go live in their family’s old summer house. There was enough furniture and old clothes left there for the two of them, and it suits them. They keep animals. Pindar still has their old car, so he can sometimes go into town for things they need. “Pindar” was one of the words in the inscription on the rock.

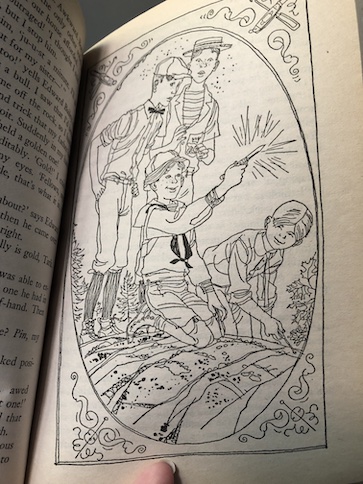

Pindar explains that he and his best friend when he was a kid, Tarquin (another of the words on the rock), were the ones responsible for the inscription on the rock. Tarquin was three years older than Pindar, but they were still close friends. However, they had a temporary falling out when Tarquin was 13 years old. Tarquin had gone away to boarding school for the first time, and the next time they met at their summer homes, Tarquin had brought a friend from his new school with him, Edward. Tarquin and Edward were putting on airs and showing off how sophisticated they were because they were 13 years old and knew so much more now that they had been to boarding school. Pindar felt bad about his old friend shunning him and treating him like a little kid, so he started hanging out with his other best friend, Barney. Then, Pindar had the idea of showing Barney the big rock with garnets stuck in it where he and Tarquin used to meet and hang out together.

When Pindar and Barney got to the rock, they discovered that Tarquin and Edward were already there, and the older boys said that they had claimed the rock for themselves. They called the rock the philosopher’s stone and wrote the inscription labeling it as the philosopher’s stone in Latin, which they had learned at their boarding school. The older boys said that the younger ones were too little to be philosophers, like the two of them. Pindar’s feelings were hurt all over again, and he told his father about the situation. Pindar’s father was amused by the older boys and their sophisticated philosopher talk. He said that there was no age limit on who could be a philosopher and explained to Pindar what a philosopher’s stone was supposed to be and how it was supposed to turn things to gold. Then, he suggested a prank that Pindar and Barney could play on the older boys, convincing them that the stone really did have the power to turn things to gold. The older boys were temporarily fooled by the trick. At first, Tarquin was angry about being tricked, but then, he had to acknowledge that he had provoked Pindar and that the trick was a clever one. Tarquin made up with both Pindar and Barney, and he added Pindar’s name and his own to the inscription on the rock. Pindar still considers Tarquin and Barney to be his best friends, and they still write letters to each other in their old age.

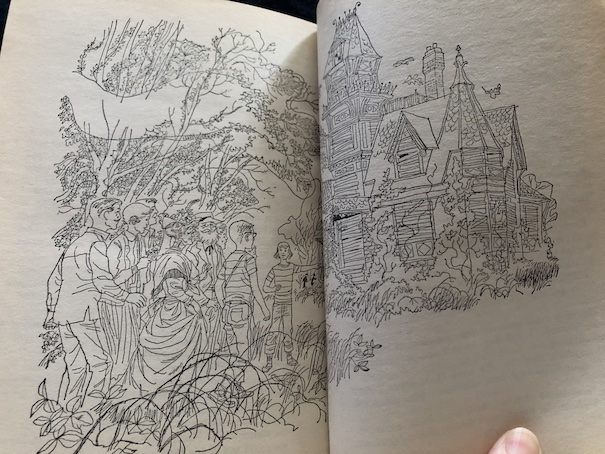

Julian and Portia are fascinated by the stories that Pindar tells about the childhood summers he and his siblings and friends spent at this now-vanished lake. Mrs. Cheever said that she loves having children around the place again, and she suggests that Julian and Portia could use one of the old houses that is still in reasonably good condition as a kind of clubhouse. Julian and Portia love the idea, and Pindar and Mrs. Cheever suggest that they use the old house where Tarquin and his family used to stay. It’s in disrepair, but it’s much better than some of the other houses. There is plenty of furniture in the attic that the children can use, too. The children decide to invite some other kids to join them, and they call their club the Philosopher’s Club, after Pindar and Tarquin’s old group of friends.

Julian and Portia invite some other local children to join the Philosopher’s Club and spent a magical summer exploring this abandoned community, picking blackberries, learning about local plants and their uses, and scavenging things from old houses and trying on the clothes from Pindar and Mrs. Cheever’s youth. The boys help Pindar build a bridge over the large sinkhole they call “the Gulper” after Foster falls into it and has to be rescued. When Julian and Portia’s parents meet Uncle Pin and Aunt Min (as they come to call Pindar and Mrs. Cheever) and come to see Gone-Away Lake, the adults also experience the magical, dream-like qualities of this place, and Portia’s parents consider plans that may make the children’s future summers magical.

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive (multiple copies – including a couple of copies of the sequel, Return to Gone-Away).

My Reaction

I remember a teacher reading this book or part of it to us when I was in elementary school, but I couldn’t remember much about the story except for the lake that had gone away and caused the town to be largely deserted. For some reason, I had thought this story was a mystery story, but it’s not.

In many ways, I think this is the perfect nostalgia book because a large part this story is about the nostalgia that the elderly brother and sister in the story have for the place where they used to have their childhood summer adventures, even though the place isn’t what it used to be. Through the stories that they tell the children and the children’s own adventures and explorations of this largely abandoned summer community, they begin building their own attachments to the place and their own nostalgic summer memories.

Because the story takes place in such a unique location, I think it would make a fun kids’ movie with a vibe of nostalgic summer adventure. Although, because the story is largely low-key slice-of-life and the flashbacks of Uncle Pin and Aunt Min to incidents in their youth, I can see that the story might have to be changed a bit to fit the usual movie format, focusing on one definite problem or a particular adventure to give the story its climax. I picture the kids and their Philosopher’s Club making it their mission to preserve this vanishing community, which fits with the way the original story goes, although the kids in the book enjoy the old community for the magic of its dilapidated state rather than wanting to fix it up and restore it to its former glory. I think they could lean into promoting the preservation of nature and the ecosystem of the area, with Julian in particular pointing out what makes this environment unique and how it has become home to animals and insects since the lake changed to a swamp and most of the people left. The Philosopher’s Club might connect with a local naturalist society, and they could build the bridge in the story together to make the swamp safer to traverse for nature lovers and bird watchers. Uncle Pin and Aunt Min could remain on the site as its caretakers. Perhaps, the kids might even find some old notes and drawings in one of the old houses that show some interesting aspects of how the environment has changed and some of the unique animals that make their home there. That didn’t happen in the book, but it would be a sort of environmentally-connected treasure the children could find.