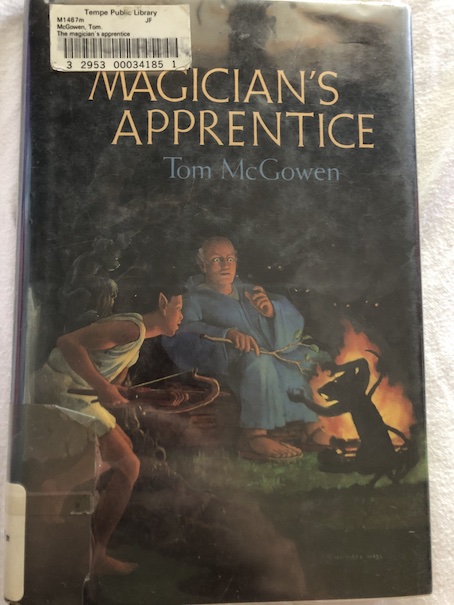

The Magician’s Apprentice by Tom McGowen, 1987.

From the title of this book and others in this series, it sounds like the stories take place in a fantasy world. When you’re reading this book, it seems like fantasy at first, but it’s not. It’s actually science fiction.

Tigg is a poor orphan boy who makes his living in the city of Ingarron as a pickpocket because he has no other means for survival. One night, he notices that a sage has left the door to his house open, and although it’s a risk, he decides to enter and see if he can find anything worth stealing. The sage, a man called Armindor the Magician, catches Tigg. In fact, Armindor had deliberately left the door open for Tigg to enter. When, Armindor questions Tigg about who he is, Tigg says that he’s about 12 years old (he’s unsure of his exact age and defines it in terms of “summers”) and that he has no family that he knows of. He lives with an old drunk who makes him pay to live with him with the money he steals.

Tigg asks Armindor what he plans to do with him. He can’t really punish him for stealing from him because Tigg hadn’t had a chance to take anything of Armindor’s before he was caught. Armindor says that’s true, but he was planning on stealing something, so Armindor tells him that he will do the same to him – plan to take something he has while still leaving him with everything he has. Tigg is confused, and Armindor explains his riddle. He witnessed Tigg picking someone else’s pocket and was intrigued by the boy because he seemed to possess courage, wit, and poise. He left his door open for Tigg because he has been looking for a young person with those qualities to be his apprentice. If Tigg becomes his apprentice, he will have to put his good qualities to use for him, but yet, he would keep these qualities for himself as well.

Tigg likes the praise but has reservations about becoming a magician’s apprentice because an apprenticeship would limit the freedom he currently has. His current existence is precarious, but the long hours of work and study involved in an apprenticeship sound daunting. However, Armindor isn’t about to let Tigg get away. He takes a lock of Tigg’s hair and a pricks his thumb for a drop of his blood and applies them to a little wax doll. He tells Tigg that the doll is a simulacrum and that it now contains his soul, so whatever happens to the doll will also happen to him. If Tigg runs away from his apprenticeship, Armindor can do whatever he likes to the doll as his revenge or punishment. Tigg, believing in the power of the simulacrum and feeling trapped, sees no other way out, so he becomes Armindor’s apprentice.

Although Tigg is fearful and resentful of his captivity as Armindor’s apprentice, it soon becomes apparent that life with the magician is better than what he used to have living with the old drunk. Armindor gives him a better place to sleep and better food. There is work and study, but it’s not as difficult or unpleasant as Tigg first thought. At first, he is daunted at the idea of learning to read and do mathematics, but Armindor is a patient and encouraging teacher, and Tigg soon finds that he actually enjoys learning things he never thought he would be able to do.

Armindor’s magical work seems to mainly involve healing sick people. When people come to him with illnesses, he gives them medicines that he calls “spells.” He keeps a “spell book” with instructions for remedies that he’s copied from other sources. Armindor teaches Tigg about the plants he uses in these spells. Armindor also does some fortune-telling, and he teaches Tigg that, too.

However, Tigg is still uneasy because, although Armindor treats him well, he still has that simulacrum of him, and he can also tell that the money he takes in doesn’t seem to account for his personal wealth. Armindor sometimes goes to meetings with other sages, and Tigg is sure that they’re doing something secret.

It turns out that Armindor is planning a special mission involving Tigg, one that will take them on a journey through uninhabited lands to the city of Orrello. Tigg realizes that if he leaves the city with Armindor, he will be committed to whatever secret plans Armindor has. At first, Tigg wants to take the simulacrum and escape, but when Armindor intentionally leaves the simulacrum unguaded where Tigg can easily take it, Tigg realizes that Armindor is telling him that he’s not really a captive and that Armindor is giving him a choice, trusting him to make the right one. Tigg realizes that he likes being trusted and that he trusts Armindor, too. He decides to stay with Armindor as his apprentice and go with him on his mission.

Tigg and Armindor leave town with a merchant caravan. On the way, the caravan encounters a wounded creature called a grubber. Grubbers are described as furry creatures about the size of a cat and have claws, but they have faces like bears and walk on their hind legs and may be intelligent enough to make fire and have their own language. One of the soldiers with the caravan things that the grubber is wounded too badly to save and wants to put it out of its misery, but Tigg insists on trying to save it. Armindor treats the grubber for Tigg, and it recovers. It is intelligent, and Tigg teaches it some simple human words, so they can talk to it. He tells them that his name is Reepah because grubbers have names for themselves, too. Armindor asks him if he wants to return to his own people when he is well, but by then, the caravan has taken them further from the grubber’s home and people, and he says that he doesn’t know the way back, so he’d like to stay with Armindor and Tigg, which makes Tigg happy.

However, Tigg soon learns that their journey has only just begun. They’re not stopping in Orrello; they’re just going to get a ship there to take them across the sea. Their eventual destination is the Wild Lands, an uninhabited area said to be filled with monsters and poisonous mists. Tigg is frightened, but also feels strangely compelled to see the place and have an adventure. Armindor finally explains to Tigg the purpose of their secret mission.

Years ago, there was another magician in Ingarron called Karvn the Wise, and he possessed some rare “spells” that no one else had. Armindor now has one of these “spells”, which he calls the “Spell of Visual Enlargement.” Tigg describes it as looking like a round piece of ice, and when he looks through it, things look much larger than they really are. Tigg is amazed.

Anyone reading this now would know from its description that what Armindor has is a magnifying lens. Tigg and Armindor don’t know the words “magnifying lens”, which is why they call it a “spell”, but that’s what they have. This is the first hint that this book is actually science fiction, and the “spells” are really pieces of lost technology and knowledge that are being rediscovered. One of Arthur C. Clarke’s Three Laws of science fiction is “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Armindor the Magician thinks of himself as practicing magic with “spells” because he’s doing things and using things he can’t fully explain, but he’s actually a doctor and scientist. He doesn’t fully understand why these things work like they do, but he’s investigating how different forms of science, technology, medicine, and knowledge work, and he’s passing that knowledge along to his student and assistant, Tigg. So, you might be asking at this point, who made the magnifying lens and why doesn’t Armindor understand exactly what it is?

Armindor knows enough to understand that the lens is made of glass, not ice. He knows what glass is, but he says that their people don’t have the ability to make glass that clear and pure themselves. This lens is the only one of its type they have, and it’s more than 3000 years old, from what Armindor calls the “Age of Magic.” Tigg has heard stories and legends about the Age of Magic, when people apparently had the ability to fly through the air, communicate over long distances, and even visit the moon. The events that brought an end to the “Age of Magic” were “The Fire from the Sky and the Winter of Death.”

Spoiler: I’m calling it a spoiler, but it really isn’t that much of a spoiler because, by the time you reach this part in the story, it starts becoming really obvious, even if the characters themselves don’t quite know what they’re describing. This fantasy world is our world, but far in the future. For some reason, thousands of years in the future, so much of our knowledge and technology has been lost, society has reached the point where people don’t know what magnifying lenses are. Also, there are creatures in this world, like grubbers, that don’t exist in other times. Something major must have happened, and it doesn’t take too long to realize what it was. Even when I read this as a kid in the early 1990s, I recognized what the characters are talking about. This book was written toward the end of the Cold War, in the 1980s, and the concept of nuclear winter was common knowledge at the time and something that was pretty widely talked about and feared, even among kids. We know, without the characters actually saying it, that the winter was caused by nuclear weapons rather than an asteroid striking the Earth because Armindor knows from writings that he’s studied that animals mutated after the “Fire from the Sky.” An asteroid or massive eruption can cause climate change due to debris in the air, but they wouldn’t cause mutation like the radiation from a nuclear explosion would. People also mutated, and Tigg and Armindor and other people now have pointed ears. People have been like that for so long, they think of it as normal, and it’s only when Armindor explains to Tigg about the concept of “mutation” that Tigg wonders what people in the past looked like.

Armindor explains that Karvn had a nephew who was a mercenary soldier. One day, this nephew came home, seriously wounded. He died of his wounds, but before he died, the nephew gave Karvn this lens, explaining that it came from a place in the Wild Lands. He said that there were many other types of “spells” and magical devices there left over from the Age of Magic. The nephew and his friends had hoped to make their fortune selling the secret of this place, but there was a battle, in which the nephew was seriously wounded and his friends were killed. He told Karvn where to find this place in the Wild Lands, but Karvn was too old to make the journey himself. He wrote an account of his nephew’s story, and after his death, all of his belongings and writings became property of the Guild of Magicians, to which Armindor also belongs. Armindor has studied Karvn’s writings, and he thinks he knows where to find this place with magic and spells, and he is going there to claim whatever he can find on behalf of the Guild.

There is danger on this journey. These lands, which Armindor says were once one country long ago, are now smaller countries that war with each other. (This is probably the United States and the different lands were once individual states. When they travel across water, I think they’re crossing one of the Great Lakes, although I’m not completely sure. The author lived in Chicago, so I think that might be the jumping off point for the crossing.) There are bandits and mercenaries and the strange creatures that inhabit this land, and it’s difficult to say whether there is more danger from the creatures or the humans.

This book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive.

My Reaction

I remembered this series from when I was a kid. It made a big impression on me because of the way that technology was treated as magic. The types of futures depicted in science fiction books, movies, and tv series can vary between extremely advanced technology and civilization, like in Star Trek, and this kind of regression to the past, where even simple forms of technology that we almost take for granted today seem wondrous and are the stuff of legends. Nobody knows what the future actually holds, but I thought this series did a nice job of showing how people who had forgotten much of the everyday knowledge of our time might think and feel when encountering it for the first time, knowing that people who lived in the past were once able to make these amazing things themselves and use them every day.

Because of the mutations that have taken place in animals, probably due to radiation from nuclear fallout, some types of animals have become intelligent. The grubbers, who call themselves weenitok, are peaceful, but the reen (which Armindor realizes are a mutated variety of rat) actually want to gain access to old technology so they can conquer the humans and take over the world for themselves. These are Armindor and Tigg’s worst enemies, along with the human they’ve hired to do their dirty work. (Yes, the mutated rats are paying a human mercenary. Even the characters in the book realize that’s weird.)

When Tigg and Armindor finally reach the special place with the magical devices, it turns out to be an old military base. Much of what they find there has been destroyed by time. Armindor tells Tigg to look for things that are made out of glass, metal that hasn’t corroded, or “that smooth, shiny material that the ancients seemed so fond of” (plastic) because these are the things that are most likely to still be usable. Tigg makes a lucky find, discovering a “Spell of Far-seeing.” It’s a tube that can extend out far or collapse to be a smaller size, and it has glass pieces similar to the magnifying lens, and when you look into it, it makes things that are far away look much closer. (Three guesses what it is.) Tigg also discovers a strange, round object with a kind of pointer thing in the middle that moves and jiggles every time the object is moved but which always points in the same direction when it settles, no matter which way the object is turned. Most of what they find isn’t usable or understandable, but they do find four other objects, including a “spell for cutting” that Armindor thinks that they might actually be able to duplicate with technology and materials that their people have. Each object that they find is described in vague terms based on its shape and materials because Armindor and Tigg don’t know what to call these things. Modern people can picture what they’ve found from the descriptions, and it isn’t difficult to figure out what they’re supposed to be. Sometimes, Armindor and Tigg can figure out what an object is supposed to do just by experimenting with it, but others remain a mystery. Armindor explains to Tigg that is what magicians do, investigate and solve these types of mysteries, “to take an unknown thing and study it, and try it out in different ways, and try to think how it might be like something you are familiar with.” (They’re using a form of reverse engineering.) Tigg decides that he really does want to be a magician and make this his life’s work. He’s going to become a scientist.

I liked it that none of the objects they find are any kind of advanced super weapon or a miraculous device that instantly solves all of their society’s problems and launches them back into an age of technology (although there is an odd sealed box that proves to be important in the next book). There are no easy answers here. In the grand scheme of things, they risked their lives for things that nobody in modern times would risk their lives to retrieve, but they have to do it because, although these things are common in our time, they are unknown in theirs. If they can figure out not only how the objects work and what they were supposed to do but why they work the way they do, they can gradually rebuild the knowledge of the past. The objects that they find are generally useful. Some are labor-saving devices, some are examples of scientific principles they would use to create other things (demonstrating concepts like optics and magnetism) and one is a medical device, which if they can figure out how to use it, will help advance their medical knowledge and treatments.

One of the fun things this book inspired me to do was to look at the world around me while imagining that I had never seen some of the basic objects in the world before. This could be a fun activity to do with kids, something like the archaeology activity that some teachers of mine did with us years ago, where we had to intentionally create objects from some kind of “lost” civilization for our classmates to analyze, to try to figure out what they were supposed to do and how that civilization would have used them. But, you don’t even have to create anything if you use your imagination and try to think what a traveler from another time or another world might think if they saw some of the things in your own home right now. Imagine what someone from a world without electricity would think of something even as basic as a toaster. How would you explain such a thing to someone who had never seen anything like it?