Cheaper By the Dozen by Frank B. Gilbreth, Jr. and Ernestine Gilbreth Carey, 1948.

These are the real reminiscences of children from the Gilbreth family about their unusual childhoods during the 1910s and 1920s. There are a couple of movies based on this book, including the 2003 movie that features the dad who is a football coach, but that story is fictional and bears almost no resemblance to the actual lives of the real Gilbreth family. The older 1950 movie with Myrna Loy as the mother is closer. The only parts that they have in common are that there were a dozen children in the family, and they had some unusual systems for handling their chaotic household.

The father of the Gilbreth family, Frank Gilbreth, Sr., was a motion study and efficiency expert. He was one of the early pioneers in the field, studying the ways that people do things, whether it was routine household chores or making things in factories and trying to find ways to help them perform their tasks more efficiently. Saving time was a passion for him, and he often used his own children and household as guinea pigs for his projects. His wife, Lillian Gilbreth, was also a psychologist and engineer and was his partner in his work, continuing it after his death.

Part of the reason Frank Gilbreth was so interested in efficiency was that, in his early life, he worked with his hands and built a reputation as an efficient worker. Later, he also learned that he had a heart condition that might cause him to lead a shorter life. He had wanted a large family, and he and his wife had agreed that they wanted an even dozen of children, six boys and six girls. He got his wish, but he was concerned about helping his children to make it as far as they could through school and giving his large household a structure that would last even after he died.

The stories in this book are mostly funny stories as his children fondly remember the things their father taught them and the usual systems in their house that were designed to keep a dozen children in order. The stories jump around a bit in time, and it isn’t always clear exactly which children were alive at certain points in the stories. Whenever Jane, the youngest, is mentioned, the stories take place between 1922 and 1924, and there should be eleven living children in the family at most. Although the Gilbreths did have a total of twelve children, as they had hoped, they were all single births (no twins or other multiples), spaced out over 17 years. Also, although this book does not mention it (the sequel, Belles on Their Toes contains a brief footnote), one of the older girls in the family (Mary) died very young of diphtheria, before her youngest sister was born, so there was no point at which all twelve children were together. Even so, the Gilbreths always referred to their children as their “dozen,” and the stories make it sound like all twelve were together. (This article explains a little more about Mary’s death and its effect on her family and the reasons why the books explain little about it.)

The children’s birth order isn’t specified in the stories, but for reference, these are their birth and death dates (courtesy of Wikipedia):

Anne Moller Gilbreth Barney (1905-1987)

Mary Elizabeth Gilbreth (1906–1912)

Ernestine Moller Gilbreth Carey (1908-2006)

Martha Bunker Gilbreth Tallman (1909-1968)

Frank Bunker Gilbreth Jr. (1911-2001)

William Moller Gilbreth (1912-1990)

Lillian Gilbreth Johnson (1914-2001)

Frederick Moller Gilbreth (1916-2015)

Daniel Bunker Gilbreth (1917-2006)

John Moller Gilbreth (1919-2002)

Robert Moller Gilbreth (1920-2007)

Jane Moller Gilbreth Heppes (1922-2006)

Wikipedia also claims that there was a thirteenth baby, an unnamed stillborn daughter, but this child isn’t mentioned in the books, and I don’t know for sure if that’s true. Most of the children lived to adulthood, married, and had children of their own.

Racial Language Warning: I usually make notes about racial language in the books I review. There are a couple of things I’d like to point out, although I also have to point out that, since this book is non-fiction, the people writing it were quoting people from memory. Just be prepared for a few things that people said back in the 1910s/1920s that wouldn’t be acceptable in modern speech. They aren’t central factors in the stories, but they are there. For example, one of the children’s grandmothers used to get dramatic when threatening the children with punishment and say that she would “scalp them like Red Indians.” (I’m not completely sure if she meant that the Indians would get scalped like that or do scalping like that, but I’m guessing that she probably wasn’t being particular.) The mother of the family also frequently used the word “Eskimo” to describe bad language or “anything that was off-color, revolting, or evil-minded.” Most of the time in the book, she says it kind of like the way some people say, “Pardon my French” when using bad language, and her definition of bad language was pretty mild. I’ve never heard the word “Eskimo” used in that sense anywhere else, and it makes me cringe here. There is some pay-off to the word when a couple of pet canaries whose full names the mother had declared were “Eskimo” escaped during a boat ride, and one of the kids tries to explain to the boat captain that he’s upset about “Peter” and “Maggie” being lost but he can’t say their last names because they’re “Eskimo,” making the captain think that a couple of Alaskan natives have mysteriously disappeared over the side of his boat. It reminded me of something similar in Fudge-A-Mania, where Fudge accidentally made people think that his lost pet bird was his crazy uncle. When sharing this book with children, like other older books, it might be a good idea to make it clear that they shouldn’t try to imitate some of the expressions the book uses because it might cause problems and misunderstandings. There is also a Chinese cook in one chapter who speaks a kind of pidgin English that no one should imitate, either.

Overall, these are calm, funny stories about a somewhat eccentric family that can make nice bedtime reading. The book is currently available online through Internet Archive.

Chapters

Each of the chapters in this book talks about a different topic or period in the family’s life:

Whistles and Shaving Bristles

Whistles and Shaving Bristles

Introduces the father of the family and his experiments in motion study. Frank Gilbreth was highly self-confident and frequently took at least some of his children (and sometimes the whole family) with him on visits to factories where he was helping to increase their efficiency. He gave the children notebooks and pencils and had them take notes about what they saw.

To keep the household orderly and make sure that each child got ready for school on time and did their chores and homework, the parents instituted a chart that each child had to initial after completing certain routine tasks such as brushing teeth or making beds, and there was a special whistle that their father would give to get all of the children to come quickly for a meeting. The father would sometimes take moving pictures of the children doing chores, like washing dishes, so that he could study their motions and determine if there were wasted motions that could be eliminated so that the task could be completed more efficiently. He also used himself as a guinea pig, always trying to do daily tasks, like buttoning his coat or shaving, more quickly and efficiently.

Pierce Arrow

The family moves from their home in Providence, Rhode Island, to Montclair, New Jersey. This chapter explains the move and also the father’s love of practical jokes. Before taking the family to their real new house, he takes them to one that’s really old and run-down so that the new one will look that much better when they get there. When they get their large Pierce Arrow car, big enough to carry the whole family, the father tricks each of the kids into looking for the “birdie” in the engine and then honks the horn to scare them. He thinks it’s funny until one of the kids does the same thing to him.

Orphans in Uniform

Orphans in Uniform

This chapter explains that the mother of the family was a psychologist. While the father instituted systems and dealt out discipline, the mother was often the one who made the systems work, resolving conflicts among the children and making sure that everyone was doing what they needed to do and that they had everything they needed. Older children also helped by looking after a designated younger sibling.

Much of the chapter explains how things often happened on family outings. They always took roll call because there were a couple of incidents when children had been left behind by accident on earlier trips. As a large family, they also attracted a lot of attention. Sometimes, their father would try to get discounts on things like ticket prices and toll booths by pretending that his children were the nationality of whoever seemed to be in charge, and he was pretty good at guessing that correctly. All of the Gilbreths were either blonde or red-haired, so Mr. Gilbreth was known to gleefully pretend that they were Irish, when in fact, their heritage was Scottish. He always thought jokes like that were funny, but finally his wife and children put a stop to his playacting the day that the family was mistaken for an orphanage on an outing.

Visiting Mrs. Murphy

The family enjoyed going on picnics together. While they were eating, the father would often try to squeeze in an educational lesson, pointing out things like the way ants work together, how a nearby bridge would have been constructed, or what was going on at a nearby factory. The children learned a lot from him, especially how to notice details in the world around them, but they noted that it was their mother who often put the lessons in perspective for them by pointing out the human side of each of these things, such as describing the fat queen ant in a colony with all of her slaves (their word, I’ve usually heard them referred to as “workers”, but you get the idea) waiting on her or the workmen on a construction project in their jeans, stopping for lunch. Their father was also pleased by the mother’s descriptions, which complemented his lessons so well. These stories help explain how the parents worked well together as a team.

The “visiting Mrs. Murphy” was a euphemism for going to the bathroom in the woods because the family didn’t really trust public restrooms.

Mister Chairman

This chapter explains a little about Frank Gilbreth’s youth and how he got his start. His father died when he was young, and his mother encouraged her children to get the best education they could. However, Frank Gilbreth decided to get a job instead of going to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology like his mother planned because he was concerned about the family finances and his sisters’ education. He became a bricklayer and drove his supervisor crazy because he always had tips for working faster and more efficiently. Eventually, the supervisor adopted some of his suggestions, and Frank discovered his passion for motion study. He worked his way up in construction until he became a contractor, and he was also hired to study working methods in the factories he built. He became a wealthy man and met his wife as she passed through Boston on her way to a trip in Europe. Lillian was from a wealthy family in California, and she had a college degree in psychology. Although many people didn’t take female scholars seriously in those days, Frank did, and the two of them became a team, both personally and professionally. They were both interested in the psychology of management, and they applied many of the principles from the professional world to their household and vice versa.

To help organize household tasks and make family decisions, Frank created a Family Council with himself as the Chairman and his wife as the Assistant Chairman that was similar to an employer-employee board. For the most part, it did help to keep order in the family, but once in a while, the Chairman was overruled, including the time when the children ended up persuading their parents that they should get a family dog.

Touch System

This chapter goes into more detail about how responsibilities and chores were assigned in the family. It also describes how the father arranged to make best use of “unavoidable delay” in the bathroom by putting Victrolas with language lessons in the children’s bathrooms, so they could learn while bathing or brushing their teeth. He also taught them how to take baths efficiently, so that they could be in and out of the bathroom as quickly as possible. Mr. Gilbreth took every opportunity and free moment to improve his children’s minds, including teaching them ways to perform complex math problems at the dinner table.

While working as a consultant for the Remington typewriter company, Mr. Gilbreth developed a system for teaching touch typing, and he taught it to his children.

Skipping Through School

Skipping Through School

Not knowing how long he was going to live, Mr. Gilbreth was anxious to see as many of his children get through school as he could, and he had great confidence in their abilities, so he often pushed his children to skip grades in school, using persuasion and his bombastic personality to get their schools to agree. The children’s mother, however, saw her children more as individuals who needed time to grow up emotionally and socially as well as intellectually and tempered her husband’s enthusiasm for skipping grades.

The parents also had their children attend church and Sunday School, although the father wasn’t very interested in organized religion. Lillian volunteered for a number of church projects and committees. Once, as a joke, a friend of hers who had eight children of her own, referred her to a birth control advocate who was looking for someone local to volunteer to promote the movement. The friend thought that it was a great joke, and the family saw the humor and made the most of it when the advocate showed up at their house.

Kissing Kin

When the United States joined World War I, Mr. Gilbreth offered his services to the U.S. Army. While he was working at Fort Sill, Mrs. Gilbreth took their children (they had seven at the time) to visit her relatives in California. The Mollers were a wealthy family, and the children enjoyed being spoiled by their grandparents and their aunts and uncles after the arduous train journey there.

Chinese Cooking

At first, the children felt like they should be on their best behavior when visiting their grandparents and aunts and uncles. However, the adults were a little worried about how subdued the children were, and constantly being on their best behavior grew more difficult for the children. One day, when the adults made the children wear new outfits that they hated for a special party, the children finally rebelled and got them all wet by playing in the garden sprinklers. From then on, everyone was much more relaxed and informal.

The grandparents had servants, and Billy became rather attached to their Chinese cook, Chew Wong (I’m not completely sure if “Chew” was his real name or a nickname), who was known for being somewhat temperamental. The cook enjoyed Billy’s company also, although when Billy got troublesome, he sometimes picked him up, held him in front of the oven, and threatened to cook him. It was an empty threat, but one day, Billy (five years old at the time) pushed the cook when he was standing in front of the oven, also joking that he was going to cook him, and the cook apparently got his hands burned. (This incident alarmed me a bit. It seems that the cook wasn’t badly hurt, but still, that’s the kind of problem that horseplay like that can cause, and it could have been really serious. The cook is described as speaking a kind of heavily-accented pidgin English.)

On the way home, all of the children came down with whooping cough. When they picked up Mr. Gilbreth, Mrs. Gilbreth told him that next time, he could take the kids to California, and she would go to war instead.

Motion Study Tonsils

The family didn’t get sick very often (and tried hard to ignore it when they did), but this chapter describes what happened when the children all came down with measles and when several of them needed to have their tonsils taken out at the same time. Their father decided to turn the tonsil operations into a motion study experiment.

Nantucket

The family had a vacation home in Nantucket, Massachusetts that they called “The Shoe” (after the nursery rhyme about the old woman who lived in a shoe and had so many children that she didn’t know what to do). Although the father promised the kids that there would be no lessons and studying over the summer, he still found ways to teach them things by turning the lessons into games, like when he painted Morse code messages all over The Shoe and offered prizes to the children who could solve them.

This chapter also explains about the Gilbreths’ concept of “therbligs.” The word comes from “Gilbreth” spelled backward, and it refers to a single unit of thought or motion. Every task a person does is composed of a certain number of therbligs. Reducing the amount of time needed for each therblig makes a task more efficient. They taught this concept to their children as well, putting symbols representing the different possible therbligs on the walls of The Shoe as well.

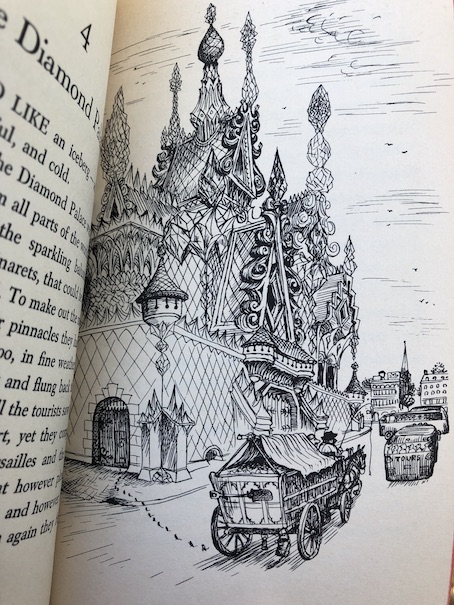

For a while, The Shoe became a point of interest on local tours.

The Rena

The Rena was a catboat that the family owned. Their father liked to run it like he was a real ship’s captain.

Have You Seen the Latest Model?

Have You Seen the Latest Model?

The births of new children were a regular experience in the Gilbreth family through much of the children’s early lives. This chapter explains how the parents approached the births. They decided very early in their marriage that they wanted a large family, choosing the number twelve as their target on the day they were married.

Mr. Gilbreth had a lot of theories about babies which he started testing on their first child, Anne. He refused to allow people to speak baby talk around the babies (although he caved in and did it sometimes himself) so they would learn to speak properly. He hired a nurse who spoke German in the hopes that the baby would start learning a second language immediately, and the nurse’s horror, he once tried to see if babies have an innate ability to swim by trying Anne in the bathtub. (No, they don’t, and he was careful not to let Anne almost drown.)

Mrs. Gilbreth had her first seven children at home, finding the hospital too dull because they wouldn’t let her work on anything while she was there. As time went on, the children in the family began to wonder more about where the babies came from, although they knew that it involved their mother spending the day in bed, the doctor coming, and sometimes hearing their mother yell (she was embarrassed that they’d noticed). Their mother tried to explain babies to them in terms of bees and flowers, but she was too shy to give them any real, direct information about it, and their father didn’t want to discuss the subject with them at all. This chapter also mentions that part of the family tradition was that the mother would read the book The Five Little Peppers to her children while she was recovering from a birth. (I also reviewed this book.)

Flash Powder and Funerals

Mr. Gilbreth loved taking pictures of his children (using a frightening amount of flash powder whenever he was in charge of it) and also frequently used pictures and movies of his children as part of his projects or as promotional images. One of the most bizarre promotions they did was when Mr. Gilbreth was hired by a company that made automatic pencils. They took pictures and movies of the Gilbreth children burying a coffin full of regular old wooden pencils. The kids had to bury the coffin and dig it up again multiple times while they took all the pictures and movies they wanted. Then, when the filming was over, Mr. Gilbreth made them dig up the coffin again and use all the wooden pencils in it so that none of them would go to waste.

Sometimes, these pictures and promotions were embarrassing to the children when they were made public and classmates and teachers talked about them at school. Some of the reporters who interviewed the family for human interest pieces made up bits of dialogue to make their stories more interesting and embarrassed the family. (Ex. “I am far more proud of my dozen husky, red-blooded American children than I am of my two dozen honorary degrees …”)

Gilbreth and Company

This chapter explains what it was like for special visitors to come to the Gilbreth house. Most people found it pretty strange, with so many young children and the strict household rules which the children would also try to enforce on visitors. The chapter mentions that Mrs. Gilbreth never liked using physical punishments on the children, but Mr. Gilbreth used them regularly. Mrs. Gilbreth kept trying to tell him that he shouldn’t spank the children on various body parts because of the harm it could do. At one point, Mr. Gilbreth asks her, irritably, “Where did your father spank you? Across the soles of the by jingoed feet like the heathen Chinese?” (It was a thing, but not exclusively Chinese.)

In particular, this part of the book describes two special visitors to the Gilbreth house: the father’s older sister, the children’s Aunt Anne, who came to look after the children while the parents were out of town, and a female psychologist who was trying to analyze the children for a paper she was writing. The children generally liked Aunt Anne, who also gave them music lessons, even though none of them had any talent for music. However, they started playing pranks on her when she started getting too militant with them, replacing the routines that their father gave them with ones of her own.

The children were more offended by the visiting psychologist, who asked them deeply embarrassing questions (ex. “Does it hurt when your father spanks you?”) and who seemed to have an agenda to prove that, while the Gilbreth children were smart, they were socially or behaviorally abnormal for living in such a large family under unusual systems. The children also played pranks on her, getting hold of the answers to the intelligence test that she was giving them so they could give her either abnormally correct answers or psychologically abnormal answers and purposely behaving abnormally in her presence, intentionally twitching and scratching themselves. Eventually, the psychologist caught on to what they were doing and left in a huff.

Over the Hill

This chapter is about family entertainment. The Gilbreths liked to go to the movies about once a week, often staying to see films twice. (Films were silent at this point.) The father loved the movies as much as the kids, if not more so. The children also sometimes put on little shows or skits for their parents. In particular, they liked to do imitations of their parents, many of which involved either taking the children places or being asked questions about what it was like to have so many children. Mr. Gilbreth also liked to do a “Messrs. Jones and Bones” cross-talk routine like the ones from minstrel shows, where a pair of actors perform pun-based jokes, except that he would play both parts himself, putting on accents like the black-face minstrels. (Ex. “And does you know Isabelle?” “Isabelle?” “Yeah, Isabelle necessary on a bicycle.”) The jokes are corny puns, but it’s a little uncomfortable now that I’m old enough to know the origin of this act. It went over my head as a kid.

Four Wheels, No Brakes

Four Wheels, No Brakes

The oldest girls in the family were getting old enough to start dating in the early 1920s, around the time that flapper culture was beginning. Their parents were fairly conservative in their habits, and the girls argued with them about being allowed to bob their hair and wear the latest fashions, like short dresses. The parents finally broke down and allowed the girls to have their hair professionally bobbed after Anne gave herself a dreadful bob. The father drew the line on make-up, however.

Motorcycle Mac

During the early 1920s, girls often referred to their boyfriends as “sheiks” in reference to the popular silent movie The Sheik. The father of the family often chaperoned his daughters on dates or had one of their brothers do it, although he eased off after getting to know some of the young men better. The younger siblings enjoyed teasing the older ones about their dates. My favorite episode when I first read this as a kid was the time when one of Ernestine’s boyfriends climbed a tree outside of her window to spy on her, hoping to see her getting undressed, and the other siblings decided to teach him a lesson by pretending that they were going to set the tree on fire and roast him alive. (They didn’t do it, they just threatened to. It’s a dangerous prank, but effective.)

The Party Who Called You…

Mr. Gilbreth knew that he had a bad heart condition even before his last two children were born, and he made preparations that would help his wife to run the household efficiently after his death. He died in his 50s while he was on his way to a series of conferences in Europe. He had called his wife from the train station and was on the phone with her when he had his fatal heart attack.

The book ends with describing what his wife and children did after his death. One of the things that I found most touching was the way that the children described the changes in their mother after her husband died. They said that in their mother’s youth, she had been accustomed to other people making decisions for her, first her parents, then her husband, who guided their work and who had the idea of the large family in the first place. In some ways, their mother had been a very nervous, anxious person, afraid of things like going out alone at night, lightning storms, and making speeches (although she did them anyway). After her husband died, Lillian’s fears seemed to drop away because the thing that she had always feared the most, losing her husband, had happened, and she discovered that she and the children could still manage. When Lillin’s mother suggested that she move the family out to California to be close to their relatives there, Lillian held a Family Council with the children to decide what they were going to do. Lillian said that she planned to continue their father’s work, even going to Europe in her husband’s place to present his papers, and that would mean that the children would have to take on greater responsibilities in running the house and caring for the younger children. The children agreed, and although money was tighter than it was before, they were able to carry on.

Whistles and Shaving Bristles

Whistles and Shaving Bristles Orphans in Uniform

Orphans in Uniform Skipping Through School

Skipping Through School Have You Seen the Latest Model?

Have You Seen the Latest Model? Four Wheels, No Brakes

Four Wheels, No Brakes

Then, the family receives word that Captain Carey’s brother is in failing health and that his business partner, Mr. Manson, is seeking to place his daughter, Julia, with a relative. Mr. Manson has already spoken to a cousin of the family about Julia, but this cousin has refused to take her. The now-fatherless Carey family knows that taking on another relative will be an added burden on them, but Julia has no other family and nowhere else to go, so they see it as their duty to help her. Admittedly, none of them likes Julia very much. They remember her as a spoiled child who was always bragging about the wonderful things that her wealthier friend Gladys Ferguson had or did. Even now, the Ferguson family has invited Julia for a visit before she goes to live with her aunt and cousins, but unfortunately, they have no intention of adopting her or even trying to care for her until her father is well themselves. Nancy sees them as simply spoiling Julia and preparing her for a life that the Carey family can’t possibly support.

Then, the family receives word that Captain Carey’s brother is in failing health and that his business partner, Mr. Manson, is seeking to place his daughter, Julia, with a relative. Mr. Manson has already spoken to a cousin of the family about Julia, but this cousin has refused to take her. The now-fatherless Carey family knows that taking on another relative will be an added burden on them, but Julia has no other family and nowhere else to go, so they see it as their duty to help her. Admittedly, none of them likes Julia very much. They remember her as a spoiled child who was always bragging about the wonderful things that her wealthier friend Gladys Ferguson had or did. Even now, the Ferguson family has invited Julia for a visit before she goes to live with her aunt and cousins, but unfortunately, they have no intention of adopting her or even trying to care for her until her father is well themselves. Nancy sees them as simply spoiling Julia and preparing her for a life that the Carey family can’t possibly support.

A character that appears in the movie, Ossian “Osh” Popham, is also in the book, although instead of being the store owner, he’s a local handyman who helps the family get the house in order. His children, also characters in the movie, are in the book, too, although I didn’t like the way the book described his daughter, Lallie Joy. It says that “she was fairly good at any kind of housework not demanding brains” and that she “was in a perpetual state of coma,” in case you didn’t understand that she’s basically stupid. I always hate it when stories make a character intentionally stupid. I did appreciate her explanation of her name, though: “Lallie’s out of a book named Lallie Rook, an’ I was born on the Joy steamboat line going to Boston.” I had wondered where the name came from.

A character that appears in the movie, Ossian “Osh” Popham, is also in the book, although instead of being the store owner, he’s a local handyman who helps the family get the house in order. His children, also characters in the movie, are in the book, too, although I didn’t like the way the book described his daughter, Lallie Joy. It says that “she was fairly good at any kind of housework not demanding brains” and that she “was in a perpetual state of coma,” in case you didn’t understand that she’s basically stupid. I always hate it when stories make a character intentionally stupid. I did appreciate her explanation of her name, though: “Lallie’s out of a book named Lallie Rook, an’ I was born on the Joy steamboat line going to Boston.” I had wondered where the name came from.

When Lemuel tells the Careys that they can stay in the house for as long as they like, unless his son Tom wants the house, Nancy begins thinking of Tom as a possible threat to her family’s happiness. (She thinks of him as “

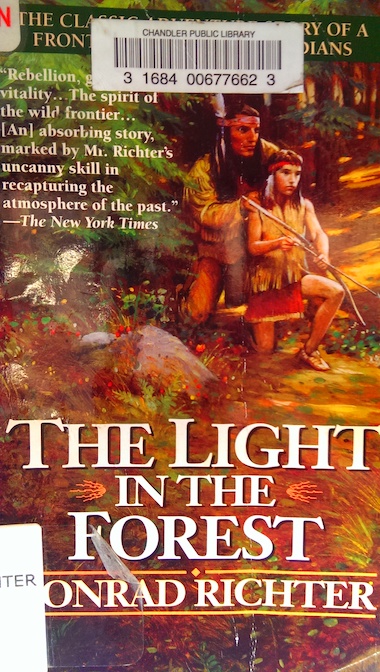

When Lemuel tells the Careys that they can stay in the house for as long as they like, unless his son Tom wants the house, Nancy begins thinking of Tom as a possible threat to her family’s happiness. (She thinks of him as “ The Light in the Forest by Conrad Richter, 1953.

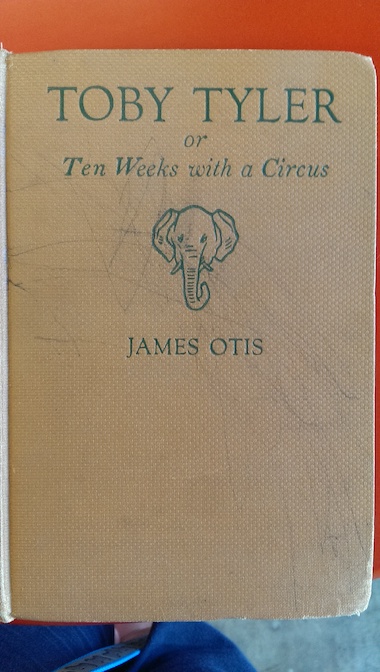

The Light in the Forest by Conrad Richter, 1953. Toby Tyler; Or, Ten Weeks with a Circus by James Otis, 1881.

Toby Tyler; Or, Ten Weeks with a Circus by James Otis, 1881. Toby think that it sounds like an exciting offer, and Mr. Lord persuades Toby that the best way would be for him to sneak away at night because his Uncle Daniel might disapprove and stop him from taking the job. Not taking that as a warning, Toby agrees. Toby feels a little guilty about running away and surprisingly homesick, but he decides to stand by the agreement he made with Mr. Lord and see what possibilities life with the circus might have for him.

Toby think that it sounds like an exciting offer, and Mr. Lord persuades Toby that the best way would be for him to sneak away at night because his Uncle Daniel might disapprove and stop him from taking the job. Not taking that as a warning, Toby agrees. Toby feels a little guilty about running away and surprisingly homesick, but he decides to stand by the agreement he made with Mr. Lord and see what possibilities life with the circus might have for him. The Lottery Rose by Irene Hunt, 1976.

The Lottery Rose by Irene Hunt, 1976.