Stonestruck by Helen Cresswell, 1995.

It’s WWII and Jessica knows that she will be evacuated from London soon, along with other children from her school. She doesn’t want to leave London and her mother, even though the bombings have gotten increasingly worse and frightening. Her father has already gone away to the front, and she has no idea if he will ever return. Then, one night, the unthinkable happens: their house is destroyed in a bombing. Jessica and her mother survive the bombing by sheltering in their basement, but Jessica’s pet cat is nowhere to be found. She doesn’t know if he survived the bombing and ran away somewhere or if he is buried somewhere in the rubble of their house. Jessica is traumatized, but with their home gone, her mother makes the decision to send Jessica away from London early. Jessica’s mother has decided that she will volunteer for service as an ambulance driver.

Jessica is terribly upset and worried about what will happen to her when her mother sends her away to Wales alone, but her mother assures her that she will be fine and that she will soon be joined by the other children from her school. They are being sent to a Welsh castle, where they will have classes together. Jessica’s mother tries to tell her that it will be fun and exciting, going to school in an old castle, but Jessica is too frightened and traumatized to think that this will be a fun adventure.

When Jessica’s train arrives at the station in Wales, she is met by Mr. and Mrs. Lockett, the gardener and housekeeper at the castle. They are friendly and welcoming to her, but on their arrival at the castle, Jessica hears a frightening scream. The Locketts don’t explain to her what the sound is and act like they haven’t heard a thing. When Jessica wakes up early the next day, she is relieved to see a peacock on the castle grounds, who gives the same strange cry that she heard the night before.

She is satisfied that the weird scream she heard has a logical explanation, but then, something else frightening happens. Although the morning is clear, there is one, strange, dense patch of mist on the castle grounds. Jessica thinks that it’s strange to see such a dense patch of mist in only one spot when there’s no mist anywhere else. Then, she hears a voice calling her name from the mist and the sound of children’s laughter. Jessica is confused because she’s only just arrived and hasn’t met anyone else there except the Locketts, and the rest of her classmates from her school in London aren’t there yet. It gives her an uneasy feeling, and when she sees a hand reach out of the mist and beckon to her, she becomes terrified and runs away.

At breakfast, Mrs. Lockett is cheerful and behaves in a perfectly ordinary manner. She expresses sympathy to Jessica over her ordeals during the bombings in London and the loss of her house and asks her what she plans to do before the other children arrive. She confides that she and her husband are not accustomed to children because they have none of their own, confirming that Jessica should be the only child in the castle right now. Jessica assures her that she can entertain herself. She asks Mrs. Lockett about the peacock that made the screaming sound, but Mrs. Lockett says that there are no peacocks on the ground and that she didn’t hear any scream. Mrs. Lockett is very disturbed by Jessica’s mention of a peacock. She says that the family that owns the castle won’t have peacocks on the grounds because they’re bad luck, and she sternly tells Jessica not to imagine things. Then, Mrs. Lockett gets a call that a train with 30 evacuees will be arriving, and she needs to help arrange accommodations for them. She leaves Jessica to entertain herself, but she warns her to stay out trouble and to stay away from the pond.

Jessica explores the grounds of the castle and meets Mr. Lockett again. Mr. Lockett, who prefers to be simply called Lockett, is kind to her, and she asks him about the peacock. Lockett seems to believe Jessica that she saw a peacock and finds it worrying. He says the same thing that Mrs. Lockett said, that peacocks are bad luck. He says that, for most people, a peacock’s cry means coming rain but that it means tears at the castle. He says that he knows that Jessica is sad right now, but he says that she should remember that she won’t always be sad. Some day, she will be happy again. He also cautions her to be careful what she wishes for.

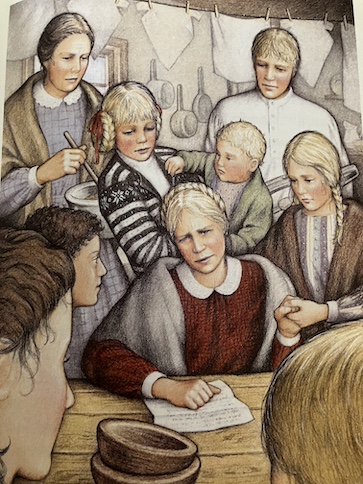

When Mrs. Lockett returns, she says that she’s made arrangements for the evacuated children who are coming. She is sympathetic to the evacuees. Arranging housing for them is a hassle, although she says it’s for their own good to be evacuated. Lockett says that it’s good up to a point. He doesn’t speak much, but he observes that, while it’s necessary for the children to be sent away from the bombings, it isn’t so good that they’re being separated from their parents. He says that he’s sure that Jessica would rather be with her mother. Jessica is surprised that he understands how she feels. She says that, while the castle is nice and definitely safer than London right now, she really misses her her mother. Mrs. Lockett doesn’t want to dwell on that. Instead, she encourages Jessica to come with her to meet the evacuees’ train. She says that these new children from London will be friends and company for her. Jessica isn’t so sure because these children are strangers to her, not friends from her school, but she does go to meet the train with Mrs. Lockett.

People from the village have gathered to meet the other evacuated children. Some of the women have prepared food for children’s arrival, and some are talking about how many children they’ve been told to accept into their homes and their fears that some of them will have lice. When the children get off the train, Jessica can see that they are all hesitant and scared. Among the crowd, Jessica sees a boy she recognizes from the night of the bombing, standing outside of a burning house. She doesn’t know his name, but she feels a kinship with him because he also lost his home. Unlike the other children, he has no bags with him. Then, suddenly, the boy vanishes in the steam from the train. No one else seems to notice that he was there or that he’s now missing. Jessica wonders if she just imagined him.

The children’s teacher is checking the children’s names off a list as they are assigned homes, but Mrs. Lockett stops her, saying that she’ll see to it herself. However, Jessica notices that Mrs. Lockett puts it off. Jessica asks Mrs. Lockett how many evacuees there are, and she vaguely says about 20 or so, when she had said 30 before. When Jessica asks her again exactly how many there are, Mrs. Lockett says that it’s an old superstition in their town, that no one should ever count children twice. Jessica asks her why that is, but she brushes off the question. Later, Jessica sees Mrs. Lockett burning the list of evacuees. With the list gone, no one will be able to count how many evacuees there are.

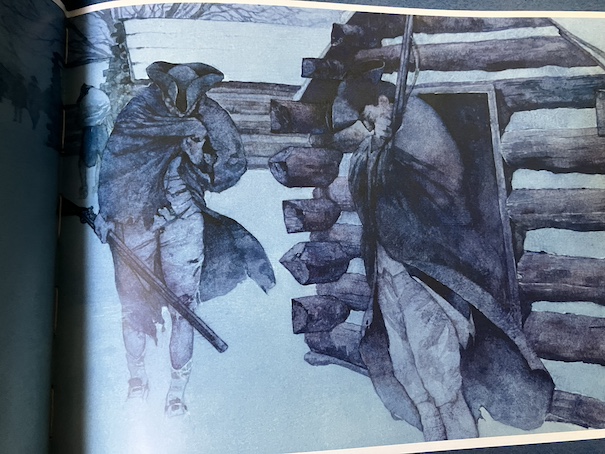

After her mother calls the castle to check on her and tries to pretend that things are fine when Jessica knows they’re not, Jessica feels the need to go for a walk by herself. Mrs. Lockett lets her go, warning her to be back before dark. As Jessica explores the castle grounds, she experiences more strange phenomena. She sees the peacock and the mist again and hears a voice calling her name. She sees a boy on a horse vanish into the mist. Then, a troop of phantom children charge past her, laughing and calling her name, and Jessica is shocked to see that one of them looks like her!

Jessica knows that she’s not just imagining the things that she’s been seeing, and she struggles to understand what’s happening and what it means. She realizes that, every time something strange happens, she either sees the peacock or hears its cry. She also remembers that, the first time she heard its cry, she had the strange feeling that, while she went into the castle, a part of herself stayed outside. Is that other part of her the phantom girl that she saw, being chased by the other phantom children? It looked like her, but it also felt alien, like it isn’t really her.

Jessica discovers that the boy who vanished at the train station ran away and has been hiding out on the castle grounds. He was afraid to let himself be sent to a strange home with the other evacuees because he’s heard that evacuees are treated horribly. Jessica tells him that she’s been treated kindly at the castle. Before she can learn the boy’s name, he runs away again, frightened by a strange old woman.

The old woman is frightening and seems to know who Jessica is. She says that she’s going about her rounds, leaving food out for the children. She knows about the phantom children, who run around in the mist with their hands linked. She refuses to tell Jessica her real name, just telling her to call her Priscilla, and she warns Jessica to keep repeating to herself that things aren’t always what they seem.

Jessica asks Mrs. Lockett if she ever played chain tag, the type of tag game where children join hands whenever they’re caught and then continue chasing other children. Mrs. Lockett says that the children around here call that game Fishes in a Net. When there are four or more children in a chain, they surround other children to trap them. She says that she played it in another place as a child, but not here because their mothers would never allow them to. Jessica asks why, and Mrs. Lockett hesitates to answer, but she makes a reference to a boy she knew when she was young, who apparently played the game too many times and disappeared. Before he disappeared, he talked about the peacocks, which was why they decided to get rid of the peacocks on the grounds. Mrs. Lockett says that the Green Lady wanted him for her own. When Jessica asks her about the Green Lady, Mrs. Lockett suddenly brushes it off as an old legend that doesn’t mean anything. Lockett the gardener says that some stories build power with the telling, and that’s why people don’t want to tell them.

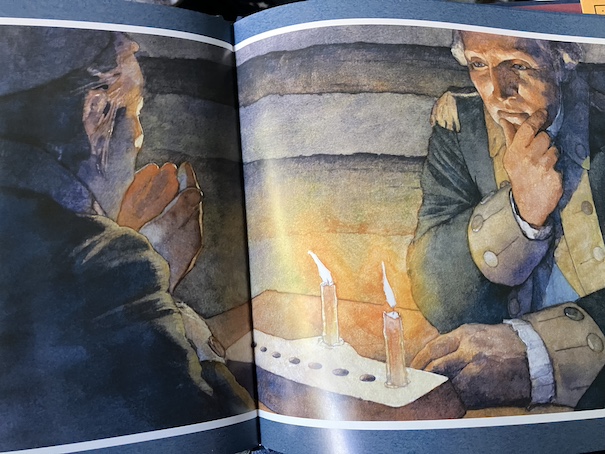

However, Jessica realizes that there is truth to the legend that Mrs. Lockett doesn’t want to explain. Mrs. Lockett knows that there’s enough truth to it to destroy the list of evacuated children so it will be harder to keep track of who’s there and who isn’t. The people of this town don’t count children twice because something that lurks in the mist vanishes children away, and no one wants to notice it or admit it’s happening, that it’s been happening for generations. As long as they don’t count children twice, they can tell themselves that no one is missing and nothing is wrong, even when it is. Jessica begins writing about all of her strange experiences in the journal that her mother gave her, trying to solve the mysteries of the castle and the mist. Something in the mist is after her, beckoning her to come to it, and like the others before her, if she goes to it, she will never come back.

At Jessica’s urging, Lockett tells Jessica what he knows about the story of the Green Lady. The Green Lady isn’t human. She’s a shapeshifter with a heart of stone. Years ago, she kidnapped the young lord of the castle, Harry, because he was a beautiful boy, and she wanted him for her own son. However, Harry was desperately lonely, living only with someone who had a heart of stone. He refused to speak aloud again until he had a human playmate. So, the Green Lady began stealing playmates for him, but it was never enough. There is one playmate in particular that Harry is waiting for, the one whose name he calls in the mist. That’s Jessica. Because only Jessica, frightened and lonely in a strange land, has the ability to break the spell.

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive (multiple copies).

My Reaction and Spoilers:

Some reviewers on Goodreads have pointed out that this book is very similar in plot to an earlier book by the same author, Moondial. In Moondial, as in this book, there is a young girl who is sent away from home and encounters mysterious phenomena that involves children in past times who are suffering and need her help to free them. However, the two stories are not identical, and I like the way this particular book is framed around WWII child evacuees from London.

It is important to the plot that the child evacuees from London are scared because of the war and have been wishing that they can go home, but that they haven’t been raised in the atmosphere of fear and superstition that the children in Wales have been. They have worries, but they’re not the same worries as the Welsh people have. Jessica learns from Lockett that it is the wishing themselves away that splits the children’s spirits and leaves them vulnerable to being captured by the trapped spirit children. Lockett understands what is happening better than anyone and how the unhappy children from London feel because he was also once an unhappy child. He was abused at home when he was young, and he also wanted to get away. However, when confronted by the spectral children whose hearts have also turned to stone, he changed his mind and escaped their clutches. He explains to Jessica what she has to do to reclaim that part of her that split off from her when she wished that she could go home, and from there, Jessica realizes what she needs to do to end this ghostly game of tag and free the other trapped children. The first step is reconciling herself to her situation as it exists and no longer wishing herself away. In doing so, she is doing what all of the adults around her have been failing to do, both about the supernatural phenomena and about the current war – facing up to the situation and not trying to pretend like it is less serious than it really while no longer wishing it away. Then, she realizes that the only way to end the spectral children’s game is to beat them at it, and for that, she needs help from other children.

When one of the other child evacuees from London has been captured and spirited away, Jessica and the boy who has been hiding out convince the other child evacuees to help them get him back and free the other children who have been taken across the generations. They have some work convincing the other evacuees of what is happening, but when they do, they form their own team for chain tag or Fishes in a Net and face off against the team of spectral children. It has to be the evacuee children who end this curse because the Welsh children are too afraid to do it, and the Welsh children’s parents would never risk them in the attempt. The Welsh people aren’t as careful about the evacuee children, and some of them have been bullying and abusing some of the evacuees. There is some concern when they realize what the evacuee children are going to do, but no one stops them.

It isn’t entirely clear what happens when the evacuee children free children who were taken from previous generations because these older children simply vanish. Even Jessica isn’t entirely sure whether the children returned to their own times or if they’ve simply passed on. However, the people of the Welsh town realize that the children have finally been freed and that the spell is broken, and they are grateful.

Parts of the story were stressful to read. First, I found the loss of Jessica’s cat upsetting. They never learn exactly what happened to the cat during the story. Then, Jessica finds out that the other boy who lost his home also lost his mother and siblings in the bombing, showing her that her own losses, while serious, aren’t the worst ones. There are also instances where the local children bully the London children, and the Welsh parents blame the London children for it. Some of the Welsh people are kind to the evacuees, but some also bully and abuse them, seeing them as only rough, poor children who are troublemakers and an inconvenience to them.

Even Mrs. Lockett says that she feels lucky that she got Jessica as an evacuee because she is gentle and well-behaved, not like the other London children. Jessica realizes that this is an unfair prejudice. Although she does not consider herself a brave person, she finds her courage when she begins to confront some of the adults around her about the way they look at the London children and how they treat them. She asks the adults directly if they realize that the London children also don’t want to be there and that no one asked them if they wanted to be sent away from their parents. The adults, confronted with the reality of the the children’s feelings and the reasons for their being there, entrusted to their care, are embarrassed. They don’t have real reasons for their prejudices against the evacuees, only their unfair feelings and bad behavior, and they realize that when they are confronted directly with the realities of the situation and their own behavior. Really, I think that facing up to realities, even ones that are strange and scary, is one of the major themes of the book. It is Jessica’s realization that she can do that, when even the adults around her can’t or won’t, that gives her the courage to do what she needs to do to end the spell and save herself and other children.