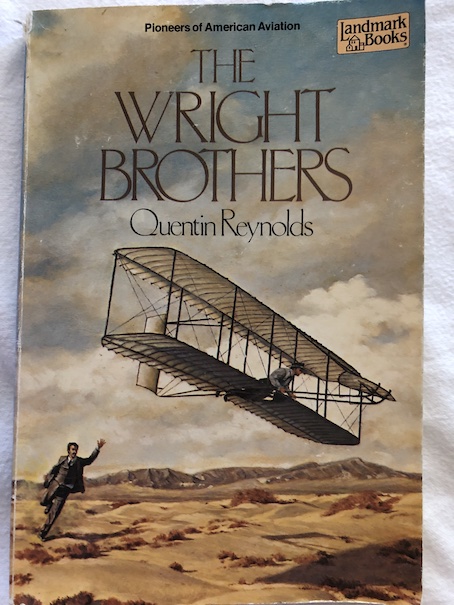

The Wright Brothers by Quentin Reynolds, 1950.

This book is part of the nonfiction history series Landmark Books, which focus on events and famous people in American history. This biography of the Wright Brothers, inventors of the airplane, is told in story format with dialog between characters. I’m not sure how accurate the dialog is, but it’s compelling way of presenting historical figures to children. I remember that I actually used this book for a report that I did about the Wright Brothers back in elementary school.

According to the story, the Wright Brothers’ mother, Susan, was responsible for inspiring their love of science and inventing things because she encouraged their curiosity and enjoyed answering their questions about how the world works, introducing them to concepts like wind resistance when explaining how birds fly and how to walk when you have to walk into the wind. Susan Wright was very good at math and had a talent for planning things out on paper that she taught to her children. She was accustomed to making her own patterns for clothes, and she showed the children how to apply similar principles to planning how to build a sled by drawing out their plan and figuring out, mathematically, the sizes of each piece of the sled. The boys learned a lot from her and applied what she taught them to their later projects, like building a wagon they could use in their first job, working for the local junk man. The boys would gather scrap materials in their wagon that the junk man would buy from them and sell to others. The junk man also gave them some supplies to work with and some tips for building their projects.

The Wright brothers enjoy flying kites with their friends, and now that they’re learning more about making things, they decide to try making their own kites. Their first attempt doesn’t work well, but by studying what went wrong, they learn how to modify different parts of the kite to get better results. Their second kite turns out better than the store-bought kites that the other boys have, and the brothers begin making and selling kites to the other boys.

When they were young, the boys were quite athletic, particularly Wilbur, who played both football and hockey. However, when he was a teenager, he was injured badly during a hockey game. A puck hit him in the face and knocked out several of his teeth. To make matters worse, the injury became infected, and the infection damaged his heart. His doctor advised him not to return to sports or athletics and not to pursue any line of work that involved hard physical work or heavy lifting to avoid further strain on his heart. It was a heavy blow, but it wad also a turn point in the brothers’ lives.

While Wilbur was resting and recovering from his injury and infection, their father gave him a drawing set and a small wood-working kit that included a book about the properties and uses of different types of wood. Wilbur had never been very interested in books before, but he discovered how useful they could be, and the boys used the new knowledge Wilbur gained in their projects. Orville made a good partner for Wilbur because he was happiest doing the actual assembly work of everything they built and had little interest in books and studying. He could handle the heavy work that Wilbur could no longer do while Wilbur studied design techniques and mapped out plans for their projects. In this way, the boys made a chair for their mother as a present. Wilbur came up with the basic concept and then discussed and worked out the plan with Orville. Orville gathered the materials and assembled the chair according to the plan, discussing the results with Wilbur. As Wilbur recovered further, he was able to get out of bed and help Orville more in their workshop in the family’s barn, but they continued to keep this partnership system that worked well for them, with Wilbur focusing on studying and planning and Orville handling the heaviest parts of the assembly.

The boys’ father was a minister, and for a time, he was the editor of a church newsletter. He gave Wilbur the job of folding the papers, with Orville helping. When they realized just how long it took to fold individual papers, they came up with the concept of building a paper-folding machine. Their machine worked incredibly well, finishing all the folding that ordinary took them a couple of days in the space of a couple of hours. Their father was amazed and realized that the boys could have a future as inventors.

In high school, Orville helped a friend of theirs, Ed Sines, with managing the school newspaper, which was printed on a very small printing press. He and Wilbur discussed making a larger press and starting their own newspaper with their friend. This was a harder job that required the boys to work with metal instead of just wood, but they accomplished it. There was one other obstacle, though. They had their own press, but before they could begin printing anything or selling advertising space in their paper, they needed to buy other supplies, like ink and paper. They realized that they and their friend would have to get other jobs to raise the money. Wilbur was the older of the two brothers by four years, and he thought he could get a job delivering groceries. However, Orville was worried that the job might be too difficult physically for his brother because it involved heavy lifting. He suggested that Wilbur get the job and then let him help with the heavier parts of the work. It turned out to be a good idea because they were able to gather pieces of news as they traveled to farms in the area and talked to people as they delivered groceries.

Their newspaper was successful, particularly after they started taking side jobs, using their printing press to print signs, flyers, and bulletins for local businesses and churches. Because it was just a small business, they underbid some of the bigger, established printers. However, the brothers soon became bored with the newspaper and printing press because what they really loved most was building things and fixing things. They sold their share in the printing business and newspaper to their friend, Ed Sines, and they decided to open a bicycle shop, where they could build and repair bicycles.

Orville had the idea of promoting their bicycle business with a bike race. His thought was that he could enter it himself and show off how their methods of cleaning and repairing bicycles improved their speed and performance. Unfortunately, the bike race didn’t turn out well. Although Orville’s bike was in excellent condition, they neglected to put new tires on it. He was just about to win when he blew a tire, and his loss of the race cost them business. People weren’t confident that they would do a good job repairing their bikes if they couldn’t properly take care of their own. However, a local businessman loved the bicycle race so much that he decided to sponsor another one, and Orville easily beat all of the other bicycles in that race. Customers’ confidence in their business was restored, and they learned that, when building or repairing any machine, they couldn’t afford to neglect any part of it or take it for granted that everything was right without checking for certain.

The Wright brothers began building their own bicycles, which they called Wright Fliers, and their mother bought an interest in the business to give them some money to get started. One of the features of their service that drew customers was their promise to repair any bike they sold for free for a full year after the purchase. When their mother died, they threw themselves even more into their business to work through their grief.

Then, Orville became ill with typhoid. It was a frightening and often deadly disease, and Wilbur and their sister Kate feared for him. The book (which was written in 1950, remember) discusses how typhoid was little understood at the time. Doctors at the time didn’t fully understand how it was transmitted. (Answer: It’s a bacterial infection spread through food or water contaminated with Salmonella Typhi. Besides vaccines, water purification methods, pasteurization of milk, and other food safety measures help prevent the spread.) They had no cure for it (which would be antibiotics later), only medicines that they could use to treat the symptoms, to try to help the sick through the worst of it. The book further notes that, by the time the book was written, most parents had their children vaccinated against typhoid and other dangerous diseases, like smallpox, but that wasn’t an option for the Wright brothers because those vaccines had not yet been developed in their time. (The book adds that, “Every single soldier in World War II was inoculated against typhoid fever, and very few of them caught the disease.” The author of this book was aware that this particular vaccine was not 100% effective and didn’t prevent 100% of cases, which is common among vaccines in general, but it was still massively effective and made a major difference in curbing the spread of the disease, even in wartime conditions, which are often unsanitary. The earliest typhoid vaccine dates back to 1896, and that was the year given for Orville’s illness, but the implication is that he caught the disease before he had access to the new vaccine. Missed it by that much.)

Orville’s illness was severe. He spent about two weeks just sleeping, and when he was awake, he was delirious because of his high fever. Wilbur and Kate looked after him with the help of a hired nurse. The doctor told them that there was little that he could do and that the fever had to “run its course.” (The book says at this point that, “You never hear a doctor say, “This disease has to run its course” today. Today doctors know how to fight many kinds of diseases, and they have medicines and drugs to kill the germs that cause the disease.” By 1950, when this book was written, the invention of antibiotics had made an enormous difference in treating infections, and the author of the book would have been aware of the difference it made in quality of life and the treatment and survival rate of diseases. However, I have to admit that it’s not true that all diseases have a cure, even in the 21st century. We have ways of treating viruses, but we still can’t really cure viruses, and most of those also have to run their course. For most of my life, people considered most viruses relatively mild compared to bacterial infections, but the coronavirus of the early 2020s challenged that assumption. It’s just interesting to me to compare these different expectations regarding illness and medicine in three different time periods: the late 1800s, the 1950s, and the 21st century.)

After about three weeks, Orville’s fever finally broke, and they knew that he was going to survive. He had lost weight, and he was very weak, and his doctor told him that he would have to rest in bed for two months. For a young man as active as Orville, that was going to be difficult, but Wilbur told him that he would read to him to keep him entertained. In particular, Wilbur had a book that he knew Orville would love: Experiments in Soaring by Otto Lilienthal. Ever since they had been making kites as boys, they had dreamed of one day building a kite big enough to allow them to fly in it, and that was basically what Lilienthal had done. Lilienthal had invented a glider. (Sadly, he was killed in a glider accident while trying to perfect his design in 1896, the same year of Orville’s illness.) Lilienthal was only one of many people who were experimenting with the concept of flight and flying machines in the late 19th century, but he had been one of the most successful with his designs up to that point. The brothers acquired other books and magazines about flight and the attempts people were making at building flying machines. Neither of the Wright brothers had actually graduated from high school, but their extensive reading and practical experimentation made up for the lack of formal education. Based on their reading, they developed a new goal: to build a glider that would fly farther than any that had so far been created.

At first, they didn’t want to tell anyone else other than their sister what they were working on because they didn’t know for sure that they would succeed, and they thought that everyone would think that they were crazy for trying to fly. A trip to the circus, where they saw an exhibit of a “horseless carriage” (an early automobile), gave them the idea that they might be able to attach an engine to some kind of glider to propel it. Their logic was that if it could work for carriages and boats, it might work for a flying machine. They imagined that an engine could propel the glider through the air as an engine could move a boat through water, and then, the flying machine would be less dependent on the wind, which could be variable.

When they had a glider design that satisfied them, they knew the only way to know for sure how well it would work would be to try it. They didn’t want to try it in Ohio, where they lived, because there were too many hills and trees that would get in the way. They wanted a flat place with few trees and where they could find a reliably steady wind. Since they had acquired their reading materials by writing to the Smithsonian Institute, they wrote to the Smithsonian Institute to ask if they had information about places with the conditions they required. The Smithsonian Institute forwarded the letter to the United States Weather Bureau, which recommended a few places, including Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. (Fun Fact: Kitty Hawk is just a little north of Roanoke Island, the site of the infamous vanished Roanoke Colony. It’s not important to the story, but I just wanted to tell you.)

As with their first kite, their first experiment with the glider was only partly successful. It glided for 100 feet before crashing. They fixed the glider and tried again, but it again ended with a crash because they couldn’t steer the glider. Just as they did with their first kite, they decided to build a new one, using what they had learned from the experiment and refining the design. They knew there were risks in their experiments because of Lilienthal’s death, but they were careful not to test their gliders at a very high altitude. They also added both vertical and horizontal rudders so they could not only steer from side to side but also move up and down, giving them greater control over the movement of the glider. What made their experiments different from others’ is that they ultimately wanted to create a “heavier than air” flying machine, propelled by an engine.

After their successful test at Kitty Hawk in 1903, in which Wilbur flew for 59 seconds, a record time, few people believe it at first. They were angry at first that their own neighbors thought that they made up the story about flying. They continued to work on their flying machine, and when they produced one that flew over a cow pasture near their town for 39 minutes, local people started believing them. Word was also spreading through the international scientific community. President Theodore Roosevelt first learned about the Wright brothers from an article in Scientific American, and he arranged for them to demonstrate their flying machine to the Secretary of War at Fort Myer, Virginia. During that demonstration, Orville flew their airplane for a whole hour, ending with a successful landing. Then, when a young soldier said that he wished he could fly, too, Orville took him for a ride with him on a second flight. The book ends with the Secretary of War hiring the Wright brothers to make bigger, more powerful airplane for the US Army, and the Wright brothers accepting an invitation to dinner from President Roosevelt.

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive (multiple copies).

My Reaction

I used this book for a school report about the Wright Brothers when I was a kid, and I think it holds up with time. Part of what I like about the Wright Brothers is their partnership as brothers. They had friends outside of the family, but their greatest friendship was always with each other because they had so many interests in common, even though there was an age gap of four years between them. They often felt like nobody understood them or their projects as well as they understood each other, and they could talk about things with each other that their other friends just wouldn’t understand because they weren’t into building things or studying technical methods and inventions. Not all siblings get along so well, but they really understood each other and complemented each other well. When Wilbur could no longer do some of the heavier work that he did when he was younger, Orville was happy to do the heavier physical work, which he preferred to the reading and studying that Wilbur discovered he really loved. They learned from a young age how to use their strengths to help each other and carry out their projects, and that’s real teamwork!

When I was a kid, I didn’t pay any attention to the About the Author section, but it’s interesting by itself. Quentin Reynolds was a famous war correspondent during World War II, which is part of the reason why he makes multiple references to World War II and World War II airplanes during the book. He also wrote other nonfiction books for adults and children, including four other books in the Landmark series.