The Court of the Stone Children by Eleanor Cameron, 1973.

Nina and her parents have recently moved to San Francisco from Nevada. Nina doesn’t like living in the city, but the move was necessary because her father has been ill and in need of a job. Still, Nina misses her friends, and her parents don’t understand how difficult Nina has found it to make friends in their new home.

One of the most popular girls, Marion Charles, nicknamed Marnychuck, and her friends like to tease Nina at every opportunity. Nina doesn’t think that she even wants to try to be friends with them because hanging out at Marnychuck’s house would mean always having to be on her guard about every little thing she says, knowing that they would twist every innocent comment she makes into some sort of joke so they could laugh at her. They could never be friends because there would be no way that Nina could ever open up to them about anything. (Sadly, I know the type all too well.) For example, one day, while the girls are walking home from school, they start talking about things they want to be when they grow up. Nina says that she wants to be “something in a museum,” momentarily forgetting the word “curator”, until a boy nearby helpfully supplies the word. Of course, Marnychuck and her friends ignore the helpful word and just laugh about “something in a museum” as they walk away.

However, the boy who was listening turns out to be genuinely curious about why Nina wants to work in a museum, saying that it sounds like an unusual ambition. Nina tells him that, until she had come to San Francisco, she’d never been in a big museum before, and she describes how the one in the park impressed her. She used to work in a small one in her home town. The boy understands the way she feels and shares her love of the past. He tells her about Mam’zelle Henry, a local woman who owns a private museum called the French Museum.

Nina visits the French Museum and loves the rooms with old-fashioned furniture. They give her a strange feeling of timelessness, and before she knows it, she finds herself in a room with another young girl who says, “I knew you’d come.” Nina isn’t sure who this mysterious girl is, but she asks her to come back another time.

When Nina returns to the museum the next day to return an umbrella that she borrowed from Mrs. Staynes, the registrar at the museum, she speaks to the girl again in the museum courtyard. The courtyard is full of stone statues of children, and the girl tells Nina that when she was young, she used to wish that they would come to life. The girl’s name is Dominique, although she says that people usually call her Domi. The two girls begin talking about their lives, although Domi oddly talks about her past in the present tense. Domi tells Nina about her emotionally-distant grandmother and her loving father, who was imprisoned and shot. The news of Domi’s father being shot comes as a shock to Nina. Domi tells Nina that, after her father was (“is”) imprisoned and shot, she had a dream about Nina in which her father said that Nina would help them. Domi also says that the rooms at the museum are from her home in France, which was taken apart to be “modernized”and some of the pieces were sent to the museum. Nina finds Domi’s story confusing, but Domi says that they will talk more later.

Nina meets up with the boy who introduced her to the museum, whose name is Gil, at the cottage of Auguste, who lives on the museum property. As she talks with the two of them and Mrs. Staynes, Mrs. Staynes brings up the subject of the ring that Nina saw Domi wearing and which also appears in a painting in the museum. Earlier, Mrs. Staynes had told Nina that she couldn’t possibly have seen anyone wearing that ring, and Mrs. Staynes now explains that the reason why is that she owns the ring herself. At first, Nina thinks that she must own a ring which is similar to Domi’s, since the two of them couldn’t have the same ring,but then, it turns out that the cat that Domi said was hers also belongs to Auguste.

The answer, as Nina discovers the next time she meets Dominique, is that Domi is a ghost. Mrs. Staynes does own Domi’s ring now because Domi died a long time ago. Nina faints when Domi’s hand goes right through hers. When Nina recovers, Domi is gone, and Mam’zelle Henry gives her a ride home. The two of them bond as they discuss Nina’s ambition to become a curator.

Mam’zelle lets Nina borrow a journal that she found in the garden that belonged to Odile Chrysostome in 1802. Odile was one of the names of the stone statues in the courtyard, according to Dominique, and Nina learns that the others are also named after members of the Chrysostome family. The people at the museum say that they don’t know which of the statues is supposed to have which name, but thanks to Dominique, Nina does.

Gil becomes Nina’s first friend her own age, and he’s been working on a project involving time. Someday, he wants to write a book about the concept of time. Time is important because Domi needs Nina’s help to resolve problems that occurred in the past.

Domi was young during the time of Napoleon. Her mother had died in childbirth along with Domi’s younger sibling. After her mother died, her grandmother moved into the house to oversee things and help care for Domi. However, Domi’s father had protested some of Napoleon’s policies of conquest, and it led to his downfall. One day, Domi discovered her father’s valet,Maurice, murdered in her father’s bedroom. She had thought that her father was there the night before, having returned from being away for a time, but he was nowhere to be found. A short time later, her father was charged with conspiring against Napoleon and executed. Domi knows that her father was innocent of the charges, and she suspects that Maurice was killed because he knew something important, but she needs Nina’s help to find the missing pieces. Domi knows that Mrs. Staynes is working on a book about her father’s life, and she doesn’t want the false accusations against him to be printed.

This book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive.

My Reaction and Spoilers

I thought that the book started out a little slowly. It takes quite a while before Nina discovers that the boy’s name is Gil or learns anything about him, and it’s about halfway through the book before Nina learns that Domi is a ghost, although there are hints before it. I knew that Domi was from the past, although I thought at first that she might be a time traveler of some kind. Even after Nina learns that Domi is a ghost, it takes a while before Domi tells Nina her full story and what she really needs her to do. The first part of the book dragged a little for me, and I was a little confused at first about why Odile’s diary was so important, but it turns out to contain the vital clues that Domi needs. Domi’s father was with the Chrysostome family at the time that he supposedly murdered his valet and was conspiring against Napoleon. There is a piece of physical evidence that proves it, and finding it convinces Mrs. Staynes to change her book.

One of Nina’s strengths is her power of imagination, and she helps Mrs. Staynes not only to see the truth about Domi’s father but to see him as a living, breathing person. Before, Mrs. Staynes’ book was mostly facts with little sense of the feelings of the living people behind it, but Nina’s discoveries and imagination help breathe life into the work. At the end of the book, the past remains unchanged (Domi’s life and that of her father are what they were before), but having the truth known gives Domi peace. Nina also makes peace with her new life in San Francisco, having discovered new opportunities and friends there as well as a nicer apartment for her family to live in.

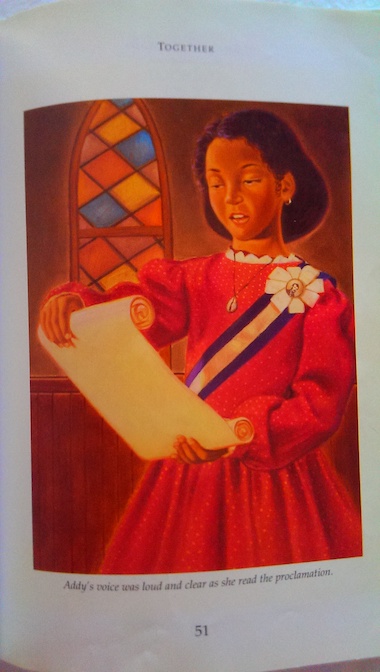

However, Auntie Lula does get to spend a little time with the family before her death, and she tells Addy not to be sad. People don’t always get everything they want in life, but they can take some pride in what they do accomplish. Lula and Solomon may not have gotten everything they wanted in life, not having had much time to enjoy being freed from slavery, but they did get to accomplish what was most important to them. Solomon died knowing that he was a free man, far from the plantation where he’d been a slave. Lula managed to reunite Esther with her family. From there, Lula says, she is depending on the young people, like Addy and her family, to make the most they can of their lives, hopes, and dreams.

However, Auntie Lula does get to spend a little time with the family before her death, and she tells Addy not to be sad. People don’t always get everything they want in life, but they can take some pride in what they do accomplish. Lula and Solomon may not have gotten everything they wanted in life, not having had much time to enjoy being freed from slavery, but they did get to accomplish what was most important to them. Solomon died knowing that he was a free man, far from the plantation where he’d been a slave. Lula managed to reunite Esther with her family. From there, Lula says, she is depending on the young people, like Addy and her family, to make the most they can of their lives, hopes, and dreams.