Ruth Fielding

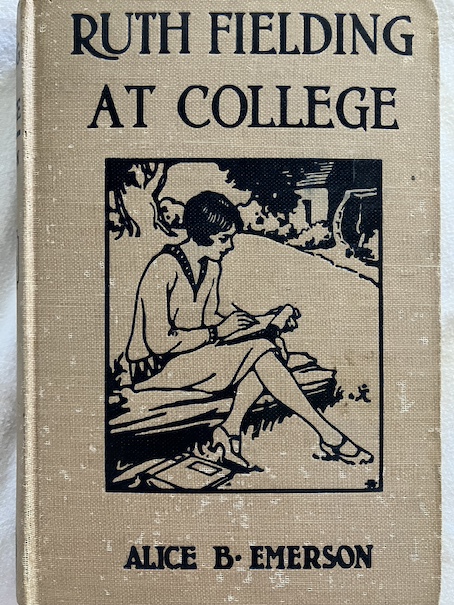

Ruth Fielding at College; or The Missing Examination Papers by Alice B. Emerson (Stratemeyer Syndicate), 1917.

Ruth Fielding and her friends have graduated from their boarding schools, and now, they’re headed off to college! Ruth and her best friend, Helen, will be attending Ardmore, a college for young women only. Helen’s twin brother, Tom, will be going to Harvard. When they were at boarding school, they also attended girls’ only and boys’ only schools, but their schools were located near each other, and they were able to visit each other on weekends and attend joint social events held between the schools. Helen and Tom are close as twins, and Helen worries that she won’t be able to see her brother as often while they’re in college. Tom and Ruth are also fond of each other, and although they’re excited about college, they’re also a little sad at the idea of being apart.

The Rescue

While they’re having tea with Aunt Alvirah (the housekeeper), the hired hand working for Ruth’s Uncle Jabez, Ben, comes in and says that there is a boat adrift on the river that runs by the mill where they live. Everyone goes outside to have a look at the boat. At first, they think no one is in it, and Uncle Jabez says, if it’s abandoned, then he will go after it as salvage. Then, they see that someone is in it after all, just lying down in the bottom of the boat, but the boat is drifting toward the dangerous rapids below the mill! Whoever is in the boat seems incapacitated or unaware of their dangerous situation.

Uncle Jabez is less eager to go after the boat when he knows there’s somebody in it than he was when he thought he could get a free boat, but Ruth persuades him that they have to rescue whoever is in the boat. They manage to reach the boat, and they find an unconscious girl in it. They bring the girl back to the house with them, and Tom says that he will get a doctor. However, Aunt Alvirah doesn’t think that a doctor will be necessary because it looks like she has only fainted, and she thinks that the girl will be all right.

When the girl wakes up, she explains that her name is Maggie and that she was working at Mr. Bender’s camp for summer vacationers up the river. After the season ended, the vacationers left, and Mr. Bender paid her for her time at the camp, someone was supposed to give her a ride across the river with her luggage, but Maggie fell asleep while she was waiting in the boat. When she woke up, she was drifting down the river alone. She got scared, and she fainted. Ruth says, if her job is over, then she has no reason to return to Mr. Bender’s camp, and Maggie says that’s true and that she needs to find another job. Ruth says they can use their telephone to call Mr. Bender’s camp to explain the situation and reassure Mr. Bender that Maggie is all right.

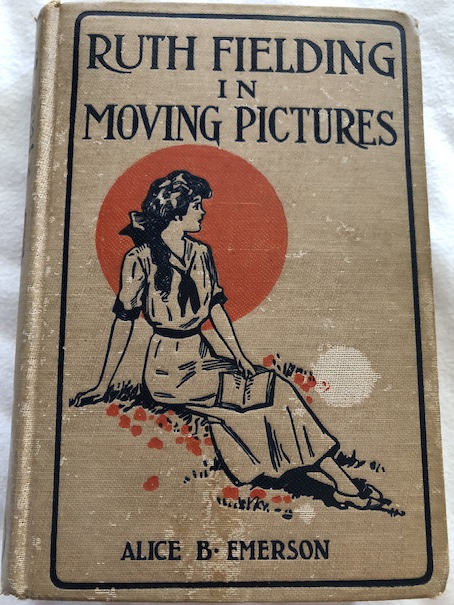

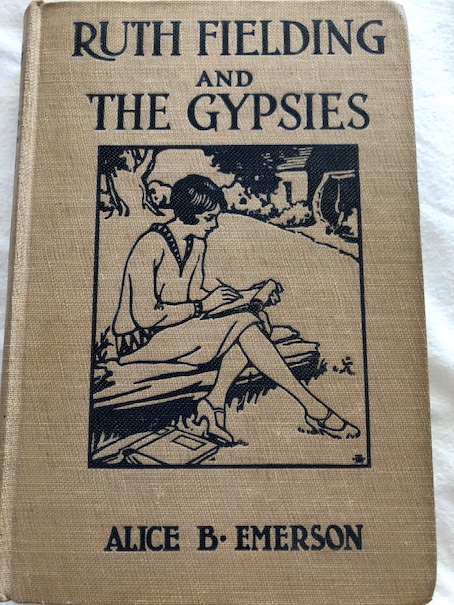

Ruth likes Maggie, and she notices, from the way she talks, that she seems more refined than most poor working girls. Aunt Alvirah is getting older, and she often has trouble with her rheumatism. Ruth suggests to Uncle Jabez that they hire Maggie to help Aunt Alvirah at the mill this winter while Ruth is away at college. Uncle Jabez is still a miser and he grumps about Ruth spending his money. Ruth has money of her own now, and she is willing to pay Maggie’s wages, although she says that Uncle Jabez must make sure that Maggie has good food because she looks undernourished. Ruth and Uncle Jabez often butt heads over the issues of money and Ruth’s education because Uncle Jabez never had much education and is both proud of the money he has now and is tight-fisted with what he has. At this point, the story explains some of the history of the characters. Since Ruth retrieved a stolen necklace for the aunt of one of her school friends and received a reward for it (in Ruth Fielding and the Gypsies), Ruth has had enough money to be financially independent of her uncle and to fund her education. She is also correct about Aunt Alvirah’s age and health, and she is concerned for the older woman’s future.

Aunt Alvirah welcomes the idea of help at the mill, and Maggie accepts the position. Ruth notices that Maggie studies an Ardmore yearbook, and she is surprised that Maggie is interested in the school. She has the feeling that there is more to Maggie’s past than she knows.

Arrival at Ardmore

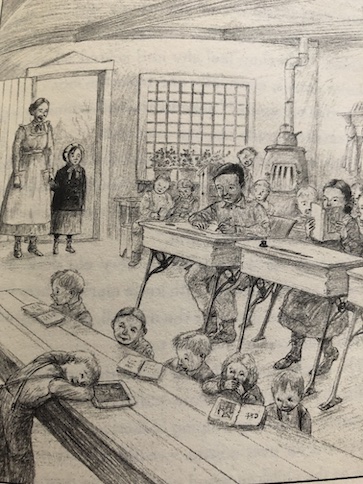

When Ruth and Helen go to Ardmore, some of the girls have already heard about Ruth’s reputation as a writer of movie scenarios from the movie that Ruth wrote and her classmates helped make to raise funds to replace a dormitory that burned at their school. Some of them are prepared to despise Ruth as being stuck up about her writing, although some who saw the moving picture liked it.

A girl named Edith thinks that they’ll have to “take her down a peg or two” as soon as she arrives. One of the other girls, Dora, reminds the others about the rules against hazing at the school. The rules have been strictly enforced since a hazing incident went too far last year and traumatized a student, Margaret Rolff, who was trying to join the Kappa Alpha sorority. Since that incident, the college has forbidden sororities to initiate freshmen or sophomore students as members and cracked down on hazing rituals. Edith, a sophomore, thinks that’s a shame because the sororities are fun, while May sarcastically remarks about how fun “half-murdering innocents” is. The students aren’t really supposed to talk about what happened to Margaret, although the sophomores don’t see why not because everybody who was at the school when it happened knows about the incident.

Margaret’s nerves were apparently shattered by the incident, and a valuable silver vase, an ancient Egyptian artifact, disappeared from the college library the same night. It isn’t entirely clear what the Kappa Alpha sorority told Margaret to do, specifically, but it seems that Margaret’s initiation task involved both taking the vase from the library and going to nearby Bliss Island alone at night. She was found there the next day in a terrible state. Nobody is sure what happened to the vase, and Margaret was apparently unable to explain it. She left the school soon after, and nobody knows where she is now. The vase might have been stolen by somebody else that night, or it might have somehow been lost in the confusion of the initiation stunt that went wrong. Because the Kappa Alpha sorority was responsible for telling Margaret to commit a theft from the school (or, at least, borrow a rare and valuable object without permission), they are raising money to replace the vase. The students’ opinions about the incident waver back and forth between thinking that Margaret was a naturally nervous and delicate person to be so dramatically affected by the incident to thinking that maybe she faked her trauma as an excuse to get away with the theft herself.

When the other girls start discussing Ruth Fielding again and how grand she must think herself, being involved with the movie industry, a plump girl who is listening to them starts laughing, but she refuses to tell the other girls why. Then, a wealthy-looking girl with a lot of fancy luggage arrives at the school, brought by a chauffeur. Her luggage is stamped with European labels and has the initials “R. F.” on it, so the other girls assume that this must be the overly-grand Ruth Fielding. The plump girl struggles not to laugh as she watches their reactions because she knows Ruth and knows that this girl is someone else.

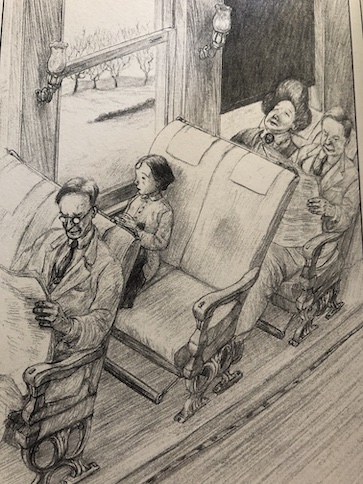

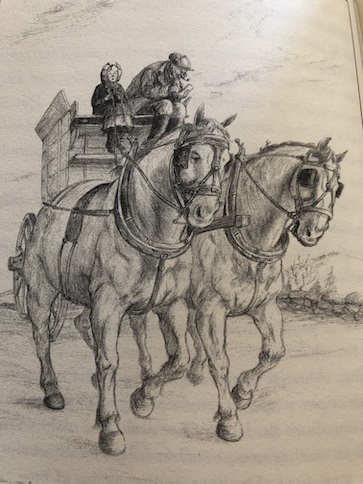

Meanwhile, Ruth and Helen have traveled to the school by train and are coming from the train station by bus. They arrive at their college dormitory, Dare Hall, just in time to see the other girls giving “R. F.” a hard time because of her fancy luggage. When Edith addresses “R. F.” as “Miss Fielding”, “R. F.” corrects her in front of the other girls, telling her that her real name is Rebecca Frayne. The plump girl, Jennie Stone, laughs at Edith’s presumptuous mistake and greets the real Ruth Fielding and Helen.

Jennie Stone was one of their fellow students at their boarding school, Briarwood Hall, in upstate New York. She was affectionately known as “Heavy” because she’s always been “plump” (or, as the book sometimes calls her, “fleshy”). Ruth and Helen are surprised to see Jennie at Ardmore because they thought that she was lacking some credits to go to college, but Jennie says that she made up those credits, and she wanted to go to college because she really had nothing to do after graduating from Briarwood but eat and sleep and put on more weight. There is some joking about Jennie’s weight, and Helen gives her a teasing pinch, but Jennie reminds her that she has feelings, too. People in Jennie’s family are naturally big, but she is determined that, as part of her college experience, she will lose weight. She wants to keep busy and reform her diet. The mathematics instructor at Ardmore has been advising her about her eating habits, urging her to eat more vegetables. The teacher seems to be hard on Jennie on the point of her weight, but the teacher openly tells her that’s only because she cares about Jennie. She knows that Jennie will want to make friends in college, and she won’t want to get a reputation as the heaviest girl in her class. It’s hard on Jennie, but she appreciates the teacher’s advice and the fact that she cares.

The mathematics teacher, Miss Cullam, also privately confides in the girls that she’s worried about the incident that happened on campus last year. She has some suspicions about the older classes of girls, although she can’t really prove anything against them. Few other people know this, but Miss Cullam admits that she had hidden some papers for last year’s mathematics exam inside the vase that disappeared from the library. It was an impulsive move and only meant to be temporary hiding place for them, but when she tried to get the papers out of the vase, she couldn’t because they were stuck. She went to get some tongs to retrieve them, but by the time she returned to the library, the vase was gone. At exam time, several students that she had not expected to pass her class did unexpectedly well on their final exam. She can’t prove that they got hold of the papers from the vase, and she hates to think that any of her students would cheat, but she still suspects they did. It bothers her that she doesn’t know for sure that they didn’t. Although the vase had value itself, the mathematics teacher’s story raises the possibility that someone knew that the exam papers were in the vase and that was the motive for the theft.

Campus Politics and the Mysterious New Girl

Ruth, Helen, and Jennie talk about the politics between the freshmen, sophomores, and upperclassmen in college. Edith seems undeterred by her earlier mistake and still gives Ruth a hard time about her writing and budding movie career. It doesn’t entirely surprise Ruth that people would give her a hard time because she is a noticeable figure among the freshmen, and having been to boarding school, she knows how things typically work among cliques and class levels at school. Although some of what Edith says embarrasses her and hurts her feelings, she knows that it’s best not to make too much fuss about the things people say, and just wait for it to blow over. It helps that Helen and Jennie stand by her and stand up to the other girls on her behalf. Ruth is somewhat reassured that hazing is forbidden at Ardmore, so she expects that little will happen other than occasional mean comments.

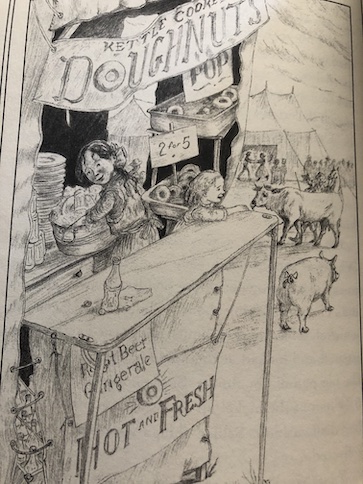

Although hazing is forbidden on campus, the college does allow the upperclassmen some privileges over the underclassmen. They do it with a purpose in mind, using it as a tool to get the freshmen to bond with each other and solidify their class leadership. Few freshmen pay attention to the elections for class president until the seniors put up notices to tell the freshmen that they must all wear baby blue tams (hats), that no other colors will be allowed, and that the freshmen only have three days to comply. The freshmen aren’t sure what the upperclassmen will do if they don’t comply, and some of them are resentful about the upperclassmen commanding them to buy new hats. Helen, like some of the others, initially thinks they should just ignore the command and not bother, showing the upperclassmen that they won’t be bossed around, but Ruth decides that she would rather buy and wear one of the tams because she doesn’t want to draw unnecessary attention to herself and maybe more resentment from the older girls on campus. When they go shopping in town, they see that every shop is selling baby blue tams, and one shop keeper (described as a “Hebrew” for no real apparent reason and having an accent that seems to indicate that he’s an immigrant) comments that blue is their class color, which gives the girls a clue that this is an organized campus tradition or stunt with the support of the local businesses. Because those tams are everywhere in town and other freshmen are buying them, even most of the reluctant freshmen end up with one of those hats. After that, the freshmen realize that they need to get serious about organizing their class leadership so the upperclassmen won’t be dictating everything to them.

There is one hold-out among the freshmen who doesn’t buy one of the tams, and that’s Rebecca Frayne. She just keeps wearing the same tam she was wearing when she arrived at school. When the three days are up, and Rebecca still doesn’t have a baby blue tam, the upperclassmen start boycotting her. If she comes to class in her usual tam, they all get up and walk out. They even walk out on meals when they see her. This seems like more of a punishment for the upperclassmen, who have to leave without finishing their meal, than it is a punishment for Rebecca, and someone does point that out.

(I see what the students say about these traditions being bonding experiences, but I really don’t have any respect for these catty and manipulative tactics because it looks dumb, and I think it just disrupts class for everyone to have so many students walking out. I think my college professors would have counted them as absent if they walked out of class over a dumb hat because student social activities need cannot impact the education they are supposedly here to receive and have no place in the classroom. Whatever they do needs to be done on their own time, not on the teacher’s or the class’s time. Actually, I did have a professor who used to award extra points to students who showed up on days when class attendance was low due to bad weather or people ditching class for sporting events. He would have us take notes or a short quiz and write a special phrase at the top of the paper as a sign that we were there that day when others weren’t, like “Rainy Day Faithful” or “Sports Day Faithful.” I kind of wanted to see the instructors in the story do something similar. On the other hand, if they self-punish themselves by sending themselves away from the dinner table, I’m inclined to think it’s deserved. I’d be inclined to let them do that until they get hungry enough to stop. It’s a rare example of a problem that will eventually solve itself.)

However, Rebecca’s apparent defiance of the social order even gets on the nerves of her fellow freshmen. The others have come to appreciate the bonding experience of buying the matching hats and solidifying their support of their own class leadership. It was a ridiculous and high-handed order from the upperclassmen, but ultimately, a fun and harmless one, a reason for a short shopping trip, and only a minor expense that supports local businesses. The other freshmen don’t understand why Rebecca isn’t joining in with them in class solidarity. Rebecca doesn’t mix much with the other students, and the others think that she doesn’t want to be friends, although Ruth can see that the boycotting she’s suffering is hurtful to her.

However, there may be another explanation for Rebecca’s behavior besides defiance or stand-offishness. Ruth begins to realize that Rebecca not only always wears the same hat but that she’s only ever seen Rebecca wear the same three outfits, over and over. They’re good quality clothes, but it’s odd that she never seems to wear anything else. Although they all saw Rebecca arrive at college with a lot of luggage, more than the other students had, she either doesn’t seem to have many clothes or never wears the other clothes she brought. From the way she arrived and the amount of luggage she had, everyone expected that Rebecca would be the wealthy fashionista of their class, but that hasn’t been the case. Is Rebecca not as wealthy as they thought, and could her choice to not buy a blue hat be because she can’t afford one? But, if her luggage wasn’t full of fashionable clothing, what was really in her large trunk? Ruth becomes concerned about her and tries to figure out what’s really going on with Rebecca.

Mystery on Bliss Island

Meanwhile, Ruth, Helen, and Jennie have been exploring the area around the college. One day, the three of them go to Bliss Island to have a look around. Jennie is hoping that hiking around the island will help her in her quest to lose weight. While they’re exploring, Ruth thinks that she sees someone else on the island. She doesn’t get a good look at this other person, but she thinks it looks a lot like Maggie. Helen thinks that she must be wrong because Maggie is supposed to be helping Aunt Alvirah back at the mill. Later, Ruth sees a light on the island at night and realizes that someone must be camping there.

When Helen and Ruth go to investigate who is camping on the island, Ruth expects to find Maggie. Instead, they find a strange girl who seems to bear a resemblance to Maggie. This other girl seems suspicious and doesn’t want to explain much about herself. What is she doing on the island, and does it have anything to do with what happened on Bliss Island during the hazing incident?

The book is in the public domain and is available to read for free online through Project Gutenberg.

My Reaction and Spoilers

The Mysteries (and some spoilers)

In a way, this story is what I had hoped that Ruth’s first adventures at boarding school in Ruth Fielding at Briarwood Hall would be like. It doesn’t have any spooky stories, but there is an unresolved mystery involving the initiation rituals of a campus sorority, the theft of a valuable object, and a possible cheating scandal. There also also mysteries about the behavior of other students and girls Ruth knows. At first, I thought there might be a connection between all of these things, but the mysteries aren’t call connected.

Ruth is correct that Rebecca isn’t as rich as she looked at first. When Ruth speaks to Rebecca privately, Rebecca explains that her family was once wealthy, and they still live in the biggest house in their small town, but the family’s fortunes have diminished over the years. Her aunt, who takes care of her, thinks it’s important to keep up appearances, which is why she has a few nice clothes but not many. The family has to make real sacrifices to keep up the pretense that they have more money than they really have, and Rebecca arrived at college thinking that she would have to make an impression on the others at the beginning that she came from money so they wouldn’t think that she didn’t belong.

Ruth explains to her that college isn’t really like that. Not everyone at college has much money, and many other girls get part time jobs, like waitress, to pay for their education. Belonging at college comes from participating in activities with everyone else, and Rebecca is pushing other students and potential friends away by not joining in the traditions of the college. Personally, I thought the other students were being too militant about this silly hat thing. I get how people can bond over shared traditions and how school traditions and spirit events are meant to be bonding experiences, but I just think that they went overboard, making too much of a big deal about this one student, with only Ruth thinking to actually talk to her and find out what’s going on with her. It does beg the question of whether the students are really focusing on this as some kind of school initiation/bonding ritual for the fun of it or because the older students are on a power trip and trying to exert control and be exclusive. In a lot of ways, I share Olivia Sharp’s feelings about exclusive clubs and initiation rituals from The Green Toenails Gang. It’s one thing if a club has a particular purpose, but being pointlessly exclusive is something else. This is something that Ruth actually addresses with the upperclassmen later, which was a relief.

However, even though Ruth is sympathetic to Rebecca, Ruth points out to Rebecca that her resistance to participation with the other students is causing problems in her relationships with others. When she doesn’t do what everyone else is doing, she isn’t sharing in their experiences and doesn’t bond with them. That’s when Rebecca says she really can’t afford to buy one of the blue tams, and her aunt would never allow her to take a part time job because that would ruin the pretenses the family tries to maintain about their actual money troubles. Ruth thinks the Frayne family pretenses are as silly as I thought the students’ militant hat ritual was, but she can see that a more creative approach is necessary to solve Ruth’s problem. Rebecca knows how to crochet, so Ruth suggests that she crochet a tam for herself in the baby blue color of their class because that would be cheaper than buying a tam. This will allow Rebecca to participate in this campus ritual and tradition but on her own terms and within her budget.

Then, Ruth quietly has a word with some of the senior students and freshman students about Rebecca’s situation to keep them from harassing Rebecca further while she’s working on her new tam and so they won’t give her a hard time about anything related to money. She even stands up to the seniors and tells them that, if their enforcement of the tam rules was for the sake of campus tradition and creating a memorable bonding experience among the students, they should have compassion for Rebecca and her situation, but if it was only to bully and exert power over the younger students, she will tell the other freshmen that’s the case, the freshmen will completely rebel, and everyone will stop wearing the hats or doing anything else the seniors say to do. If the upperclassmen continue to insist on leaving the dining hall in the face of their disobedience, the freshmen will make sure that the upperclassmen don’t eat on campus for the rest of the year. The seniors understand the situation, appreciate Ruth standing up for her classmate, and like her spirit, so they finally lay off their boycott of Rebecca.

Ruth also helps Rebecca solve her money problems when she realizes that Rebecca has brought something with her to college that is worth real money. Rebecca’s trunks were from the attic of her house, and she brought them just to create the illusion that she had more money and belongings than she really does, but she hasn’t appreciated the value of what they contain. Rebecca has many lessons to learn about the real value of many things. The contents of the trunk seemed a little anti-climactic at first because I had initially thought the story was building up the idea that she might be carrying something more suspicious, maybe something illegal or a smuggled person, but I liked the theme that Rebecca and her family know more about the superficial look of things rather than their true value.

The mystery of Rebecca and her behavior is an interesting side plot that adds dimension to the main plot and mystery, which concerns campus politics and initiation rituals and what happens when they go too far. Most of the rest of the plot and mysterious happenings centers around what happened to Margaret and the vase. In some ways, the solution to that problem turns out to be disappointingly simple. Margaret was a very nervous person who, although academically bright, was too easily influenced by other people and unable to stand up for herself. When Margaret got nervous and messed up the initiation ritual, she didn’t know how to explain herself and fix things. The situation does get resolved, and Margaret is fine. (You might have even guessed where she is through most of the story.)

However, I thought the story did a good job of demonstrating how social initiation rituals and school stunts can get out of hand when closed societies don’t consider how the things they do or ask others to do affect other people. The sorority didn’t really know Margaret as a person before they set her a task that was more difficult for her to do than it might have been for someone else, and Margaret was too timid, nervous, and anxious to be accepted by others to explain how she really felt about it or refuse to do it. This is part of the reason why the school later forbids the sororities from initiating freshmen and sophomores, so the younger students have time to get to know the campus and its groups, develop some confidence, and understand what’s acceptable for a group to ask and what isn’t. Having the sororities only recruit upperclassmen also gives them time to get to know prospective members and set appropriate tasks for people who know their own limits and when the groups are asking too much. The task should also not have involved taking a valuable object that didn’t belong to the sorority and putting it in a position where it could be lost. That is the Kappa Alpha sorority’s fault for setting a task that really wasn’t appropriate under any circumstances.

I liked the multiple mysteries of the story, the ones that connected to each other and the ones that were more stand-alone. There’s also a brief subplot where some of Ruth’s friends fake a haunting to get a relative of a faculty member to move out of her room in their dormitory so they can use the space. Before she came, that room was being used as a public sitting-room for the students, and they resent her taking it. The students involved in the plot don’t tell Ruth what they’re doing or ask her to join them, but they explain it to her when they’ve accomplished their goal. I appreciated that the plot was subtle, just making subtle noises at night using a rocking chair.

Characters That Age and Develop

Up to this point in the series, Ruth Fielding and her friends were teenagers at boarding school. Now, they’re becoming young women and young men in college. I liked how aspects of their college life resemble their experiences at boarding school, but the characters show that they are now more experienced. The things that happen with the social politics on campus build on the girls’ earlier boarding school experiences, but they are now more aware of the dynamics of these situations and how to deal with them. There are some times when it’s better to go along with the group for the sake of building friendships, but there are also sometimes when they have to stand up for themselves and others and tell the groups on campus that they’ve gone too far. There are times when it’s better to take some teasing and let it go, and there are times when teasing and enforcement of group conformity goes too far, and someone needs to be told to stop and go easier on someone. They still have things to learn, but it was nice to see their development and the use of things they have already learned. Students like Rebecca and Margaret suffer more at college at first because they are more new to the large school environment, and they don’t understand what others expect from them or when and how to stand up for themselves. They need some help from compassionate, experienced students to find their way.

Readers also see main characters are continuing to build their future lives and develop as people. Ruth has already started her writing career, and through the story, we are told that she is still working on a play she’s writing, and she and her friends also take part in the filming of another movie during a school break. Ruth is planning to go further in her writing and movie career, and she is serious about using her education to develop her career.

We don’t know as much about what Helen and Jennie are planning for their futures. Helen’s family is wealthy, so she technically doesn’t need a career, but she is a serious student. Jennie’s trait of being overweight, something which has helped to define her character through the series is interesting in this story both because Jennie stands up for herself and emphasizes that she has feelings and so more than just a fat person to be made fun of, and she’s also decided that she wants to change her image. While her teacher urges her to eat healthier, Jennie also starts joining in the sports on campus. At first, it’s difficult for her, but she gradually becomes stronger and more athletic, and she enjoys it. College is a time for people to experiment with their lives, habits, and self-image, and Jennie specifically wanted to go to college for that reason as part of her personal development.

I didn’t like the repeated references to Jennie as “plump” or “fleshy.” I did like seeing her try new activities to change her appearance and develop different sides of her personality, but the older Stratemeyer Syndicate books do have this odd focus on describing characters’ weight. Heroines are usually described as “slim” or “slender”, pleasant sidekicks are “plump”, and villains and unpleasant characters are actually fat. These designations appear repeatedly in various Stratemeyer Syndicate series, although I think they finally stopped doing it after people raised public awareness about fat shaming. In Jennie’s case, I minded it less than I’ve minded the weight references less than I’ve minded it in other books because she does remind people of her feelings and because her decision to try to improve her weight situation was her own decision rather than one she was bullied into making and is an extension of her trying new activities, experimenting with her self-image, and the college experience of personal development. Jennie was at a point in her life where she felt the need for a change, so she’s just going for it.

At this point, I want to remind readers that characters who develop and change are rare in Stratemeyer Syndicate books, at least the ones that most people remember from their childhoods, because in the series that are still in print, the characters’ ages are frozen.

Characters That Never Age

I’ve pointed this out before, but one of the hallmarks of most of the classic Stratemeyer Syndicate books that most people remember reading when they were growing up is that the characters never age. In series like Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys, they’re always in their late teens or early twenties, and their exact age often isn’t specified. Readers just know that they’re old enough to be traveling around and doing things without adult supervision, sort of like the characters in the Scooby-Doo cartoons. Also, like Scooby-Doo cartoons, the series get redone about every decade or so to update technology, slang, and world circumstances so that the books take place roughly around the time when they were written. (For example, you won’t find any Cold War references in books written after the 1990s, and existing books for series that were still in print were rewritten and reissued in the mid-20th century, around the time of the Civil Rights Movement, to remove unacceptable racial terms and stereotypes.)

However, it’s worth reminding readers that this wasn’t always true of Stratemeyer Syndicate books. The oldest series produced by the Stratemeyer Syndicate are often unknown or forgotten by modern readers because the characters did age. As the series ran their course, characters grew up, graduated from school, married, and became parents themselves. When Stratemeyer Syndicate characters got too old to be teen detectives or young adventurers, the Stratemeyer Syndicate would simply stop producing their series and start a new one, often with characters who were somewhat similar to characters in previous series but not exactly the same, so they could continue writing series with similar themes and a similar feel, but also a little different. Ruth Fielding is one of those forgotten characters because she did age, and her series ended around the time that the first Nancy Drew books were published. Nancy Drew was meant to be the next generation series to Ruth Fielding, a similar character who has investigates mysteries and has adventures with her friends, but by that point, the Stratemeyer Syndicate realized that, if they never let Nancy age, they would never have to end her series or replace her with anyone else. This is the reason why 21st century readers know who Nancy Drew is, but not many people know Ruth Fielding.

Also, because Ruth Fielding books weren’t being produced during the mid-20th century, when existing Stratemeyer Syndicate books were being revamped and modernized, the Ruth Fielding books were not modernized. The movie industry, which becomes increasingly prominent in the books, makes silent movies because the stories are set in the 1910s. There are some racial terms in books, while not being deliberately insulting, also don’t sound right because they’re not polite by modern standards. It did throw me a bit when the book referred to a shopkeeper as being “Hebrew.” I think I might have heard this before in relation to Jewish people (I can’t remember where right now, although I think it might have been an older book as well), but not often. Using the word “Hebrew” in this way is acceptable in some languages, but not in modern English, and it is considered a derogatory reference by modern standards. It took me out of the story temporarily when I got to that part because I had to stop and think it over. I came to the conclusion that the kind of person who would use “Hebrew” instead of “Jewish” to describe a Jewish person sounds like someone whose primary knowledge of Jewish people comes from reading the Old Testament rather than talking to them in life. Then, after I considered that, I had to stop and consider how Ruth Fielding could know that the shopkeeper was Jewish without even knowing his name or him saying anything about it. I suppose it might have been his general look, but that’s not always reliable. More importantly, it’s a case of the author telling us something as if it makes a difference to the character or the scene when it doesn’t. This goes absolutely nowhere. Ruth has never seen this shopkeeper before because she’s new in town, and we never see him again. This is why writers are discouraged from bringing up people’s racial or ethnic backgrounds unnecessarily because it sounds like they’re trying to make a point about something when there’s no point. This is also why I don’t mind rewrites of books that include outdated or unacceptable racial terms because I read them as a distraction that actually takes away from the story. I suppose, from a scholarly viewpoint, it’s kind of informative about the way people spoke in the past, but from the point of view of someone just trying to enjoy the story, it acts like a speed bump that shakes the reader out of it.

I don’t think the Nancy Drew or Hardy Boys books ever connect the characters with any world events with known dates because that would also mark the characters’ ages relative to events and make it obvious that they don’t age over time, but the Ruth Fielding books do connect to world events, and we’re almost to the point in the series when the characters become directly in World War I. I’ll have more to say about that when we reach that point in the series.