Ruth Fielding

Ruth Fielding at Briarwood Hall by Alice B. Emerson, 1913.

Since Ruth and her friends have helped her Uncle Jabez to recover his stolen cash box in the previous book, Uncle Jabez has decided to send Ruth to Briarwood Hall, the boarding school that her best friend, Helen Cameron will attend, so the two of them can stay together. Briarwood Hall is an exclusive school, where the primary entrance requirements are academic records and teacher recommendations. Ruth has already graduated from the local school in her uncle’s town although she is a little younger than Helen, and she is ready for the high school level. Helen’s twin brother, Tom, will be attending a military academy close to the girls’ boarding school.

The three of them travel alone to their schools, without adult chaperones. They amuse themselves by seeing if there are other students bound for their schools traveling on the same train and steamboat they take to their boarding schools, but they can’t find any. However, they do see an interesting older lady with a veiled hat who attracts their attention because she looks doll-like and speaks French. For some reason, this lady seems greatly upset by a strange man with a harp who is part of a musical group entertaining passengers on the steamboat.

The mysterious French woman turns out to be the girls’ new French teacher at Briarwood Hall. She seems very nice to the girls when they are introduced to her as they’re riding in a coach to the school after they get off the boat. Mary Cox, a fellow student who is older than Ruth and Helen, rides to the school with the girls and the French teacher. On the way to the school, Ruth notices that Mary seems to oddly ignore the French teacher, speaking only to her and Helen.

Mary is a Junior at the school, and tells the girls about the school clubs. The two main clubs at Briarwood are the “Upedes” and the “Fussy Curls.” I was glad that Ruth and Helen thought that these sounded by strange names for clubs, too. Mary explains that they’re just nicknames for the official club names. The Upedes are members of the Up and Doing Club, a group of girls who like lively activities. There are other groups at school, like the basketball players, but the Upedes and Fussy Curls have a particular rivalry for members. Mary is a member of the Upedes, although, in spite of the groups’ rivalry for gaining new members, Mary strangely doesn’t invite Ruth and Helen to join her group and doesn’t seem to want to explain what the rival group does.

When the girls leave the coach, Mary says that she doesn’t like the French teacher because she’s a poor foreigner, and Mary doesn’t know why she’s at the school. (Mary sounds like she’s rather a snob.) Mary says that she thinks it’s strange that the French teacher never wears any nice clothes and doesn’t seem to have any personal friends or relations. (Yeah, definitely a snob toward someone who just seems a bit unfortunate, like it’s some kind of moral failing, not having nice clothes or personal connections to show off.) Helen says that the French teacher does have personal acquaintances because she seemed to know the harp player on the boat, something that seems to interest Mary. Ruth has the uneasy feeling that they shouldn’t have mentioned it, not knowing exactly what the teacher’s connection to the harp player is. Helen likes Mary, but Ruth has reservations about her friendship.

Mary Cox shows the girls where their dorm room is. Helen and Ruth are sharing a room by themselves. Another girl, a senior named Madge Steel, comes by to talk to the girls and invites them to a meeting of the Forward Club (known as the “Fussy Curls” because of its initials) that evening. Ruth wants to go to that meeting because Madge seems very nice, and the Forward Club includes members of the school faculty. However, Helen says that she’d rather attend the meeting of the Upedes that evening that Mary told her about. Helen thinks that they owe Mary their loyalty because she was the first to meet them and was helpful in finding their room. Besides, the Upedes have no teachers in their club, and Helen thinks that it sounds more exciting and free from supervision than the Forward Club. Ruth thinks that she would prefer to get closer to her new teachers and some well-behaved girls instead, and it’s the first major disagreement that the friends have. Mary talks Ruth into going to the meeting of the Upedes that evening because that was the invitation that they received first, but Ruth says that she won’t join any club officially until she’s had a chance to see the other girls involved and learn what the clubs are really like. Ruth’s stance seems to be the wise one as the school’s headmistress tells the girls that joining clubs on campus are fun but that they should beware of getting involved too much with girls who don’t take their studies seriously and waste their time, and they learn that Mary Cox’s nickname at school is “the Fox”, suggesting that she’s as sly as Ruth has sensed. Although Mary didn’t mention it to the girls before, she’s actually the leader of the Upedes.

That evening, the girls are introduced to other students, and at the meeting of the Upedes, the school’s very own ghost story. Briarwood wasn’t always a school. It used to be a private mansion, and a wealthy man lived there with his beautiful daughter. The wealthy man was the one who commissioned the creation of the fountain with the marble statue that still stands on the school’s grounds. Although people on campus say that nobody really knows what the statue of the woman playing a harp in the fountain is supposed to represent, the ghost story claims that the figure was modeled after the beautiful daughter of the mansion’s former owner. However, according to the story, the girl fell in love with the man who sculpted the statue of her, and the two of them eloped, leaving her father alone and sad. Rumor had it, though, that the girl and her new husband must have died somewhere after they ran away because people started hearing mysterious harp music at night on the grounds of the mansion. Eventually, Briarwood was sold, and the school’s founders, the Tellinghams, bought it, and sometimes, people still hear harp music on the school grounds. Every time something strange or momentous happens at the school, people hear the twang of the harp.

That night, Ruth and Helen become the targets of a frightening hazing stunt by the Upedes that seems to bring the ghost story to life, but when something happens that frightens even the hazers, it brings into question how much of the ghost story is really true.

The book is now public domain and available to read for free online in several formats through Project Gutenberg. There is also an audio book version on Internet Archive.

Spoilers and My Reaction:

I liked this story much better than the first book in the series because it is more directly a mystery story than the first book, and Ruth makes a deliberate effort to untangle some of the puzzling things happening at her new school.

It’s pretty obvious that there is a connection between the ghost story of the girl with the harp and the French teacher’s apparent discomfort at the suspicious harpist. Ruth finds out pretty quickly that the harpist from the boat is lurking around the school. That revelation explains the frightening happenings at the hazing incident, although it still leaves the question of the connection between the harpist and the French teacher. At first, I thought that it was going to turn out that there is some truth to the ghost story the Upedes told, but that actually has nothing to do with the real situation. In some ways, I felt like the real situation was a little to straight-forward and resolved a bit too quickly at the end, considering the build-up they’d had about it. It is interesting that, of the students at the school, only Ruth comes to learn the full truth of the French teacher’s secret. Even Helen doesn’t know what Ruth eventually discovers, partly to save the French teacher’s reputation and partly because Ruth and Helen’s friendship is suffering for part of the book.

Unlike newer series produced by the Stratemeyer Syndicate, characters in the older Stratemeyer series, including the Ruth Fielding series, grow, age, and develop their lives and personalities. In this book, when the girls go away to boarding school, the differences in Helen and Ruth’s backgrounds and personalities become more obvious. It leads them to clash in some ways, and they both worry about endangering their friendship with each other, but by the end of the book, each of the girls develop a greater sense of who they are and what they really stand for.

Helen is more familiar and comfortable than Ruth is with the traditional rituals of boarding school, even taking some glee in the mean hazing ritual of the Upedes, and she badly wants to fit in with the cooler older girls at school, willing to put up with their mean bossing to take part in their schemes for the fun and excitement. However, Ruth, is naturally more serious and shy and less accustomed to having things her way or telling others what to do anywhere she’s lived than the wealthy Helen. Ruth overcomes some of her shyness and learns to be more assertive as she stands up for herself and the other new girls at school, called “Infants” by the older girls. Ruth decides to refuse to join either the Forward Club, which has a reputation of being made up of girls who toady up to the school faculty, or the Upedes (which was initially founded as a protest group to the Forward Club, which is why most of the activities of their club involve breaking various school rules and instigating pranks), after experiencing their mean pranks and bossiness. Instead, she takes a joke of Helen’s seriously and decides to form a secret society of her own. She talks to some of the other new girls at school, and they feel the same way they do, that they don’t want to choose between either the Upedes or the Fussy Curls and would rather have a club of their own, where they won’t be dominated or hazed by the older girls. Helen gets upset at Ruth starting this new group because she thinks that they won’t gain any new friends or have any real fun or really be a part of this school if they don’t join an already-established group. Helen thinks that a group of new girls would look ridiculous because they wouldn’t know what to do with their club and will look like a group of babies. However, Ruth realizes that this is nonsense. There are enough interested girls among the newcomers to give them a good group of friends and they can think of their own things to do where they can be the leaders. Ruth turns out to be more of a leader and Helen more of a follower, and Ruth is also more creative, thinking of new possibilities in life instead of stuck with someone else’s creation. I wish that the book had gone into more details about what Ruth’s club actually does. She and some of the other girls periodically go to meetings of their club, but they don’t say much about what they do at the meetings.

Helen and Ruth temporarily go separate ways at school. Helen joins the Upedes, and Ruth and some of the other new girls carry out the plan to form a new club that they call The Sweetbriars. The other girls who help form The Sweetbriars are as independently-minded and creative as Ruth and like the idea of forming their own school traditions. Helen criticizes Ruth for being a stickler from the rules because she doesn’t want to take part in school stunts that might get her in trouble, but although Helen is more inclined to break rules in the name of fun, she is still less independent in her mind than Ruth because her rule-breaking is done following the dictates of the Upedes and the traditional school stunts of having midnight feasts with other girls in their dorm rooms. They are not stunts of her own creation or particularly imaginative, and while she is brave about school demerits, she is not very brave about what other people think about her. After the Upedes have treated Ruth very badly and spread rumors about her, Ruth finds the courage to tell Helen how hurt she is that she continues to be friends with people who have treated her so badly when she wouldn’t have put up with people mistreating a friend of hers. She doesn’t ask for an apology and says that she’s not sure that one is even warranted, but she wants Helen to know how she feels. Helen has felt like hanging around Mary Cox has made her act like a meaner person, and she feels like she can’t help herself in Mary’s company. Understanding how Ruth really feels reminds Helen that she risks damaging her relationship with her best friend if she doesn’t do something about her behavior, and when Mary is ungrateful and lies to Helen after Ruth and Helen’s brother help save her life during a skating accident, Helen begins to see Mary for what she really is.

In the second half of the book, the Mercy Curtis from the first book in the series reappears. In the first book, she spent most of the time being bitter because she had a physical disability that prevented her from walking, and she was overly sensitive about how people looked her. However, at the end of the first book, Mercy received some treatment from a surgical specialist that has enabled her to regain her ability to walk. She still walks with crutches, but her spirits have improved now that she is able to move more easily on her own, without relying on her wheelchair. Because she had previously spent much of her time alone, studying, she qualifies for admittance to Briarwood and decides that she would like to join her friends, Ruth and Helen. When Mercy comes to the school, she is still sharp-tongued, although less bitter about herself. She rooms with Ruth and Helen and joins the Sweetbriars. She adds a nice balance to Ruth and Helen’s friendship. Ruth gets to spend some time with Mercy and the other Sweetbriars when Helen is with the Upedes, and Mercy is very serious about her studies, so she insists that her friends not neglect theirs, keeping then on task in the middle of their social dramas.

As a historical note, there is a place in the story in, Ch. 22, where the book describes Ruth as wearing a sweater, defining it as if readers might not know exactly what a sweater was, calling it “one of those stretching, clinging coats.” The reason for that is that sweaters were actually a relatively new fashion development for women in 1910s, although men had worn sweaters before. Women often wore shawls in cold weather before sweaters became popular, but sweaters left a woman’s arms more able to move freely than a shawl would allow, as this video about women’s clothing during World War I from CrowsEyeProductions explains.

Then, the family receives word that Captain Carey’s brother is in failing health and that his business partner, Mr. Manson, is seeking to place his daughter, Julia, with a relative. Mr. Manson has already spoken to a cousin of the family about Julia, but this cousin has refused to take her. The now-fatherless Carey family knows that taking on another relative will be an added burden on them, but Julia has no other family and nowhere else to go, so they see it as their duty to help her. Admittedly, none of them likes Julia very much. They remember her as a spoiled child who was always bragging about the wonderful things that her wealthier friend Gladys Ferguson had or did. Even now, the Ferguson family has invited Julia for a visit before she goes to live with her aunt and cousins, but unfortunately, they have no intention of adopting her or even trying to care for her until her father is well themselves. Nancy sees them as simply spoiling Julia and preparing her for a life that the Carey family can’t possibly support.

Then, the family receives word that Captain Carey’s brother is in failing health and that his business partner, Mr. Manson, is seeking to place his daughter, Julia, with a relative. Mr. Manson has already spoken to a cousin of the family about Julia, but this cousin has refused to take her. The now-fatherless Carey family knows that taking on another relative will be an added burden on them, but Julia has no other family and nowhere else to go, so they see it as their duty to help her. Admittedly, none of them likes Julia very much. They remember her as a spoiled child who was always bragging about the wonderful things that her wealthier friend Gladys Ferguson had or did. Even now, the Ferguson family has invited Julia for a visit before she goes to live with her aunt and cousins, but unfortunately, they have no intention of adopting her or even trying to care for her until her father is well themselves. Nancy sees them as simply spoiling Julia and preparing her for a life that the Carey family can’t possibly support.

A character that appears in the movie, Ossian “Osh” Popham, is also in the book, although instead of being the store owner, he’s a local handyman who helps the family get the house in order. His children, also characters in the movie, are in the book, too, although I didn’t like the way the book described his daughter, Lallie Joy. It says that “she was fairly good at any kind of housework not demanding brains” and that she “was in a perpetual state of coma,” in case you didn’t understand that she’s basically stupid. I always hate it when stories make a character intentionally stupid. I did appreciate her explanation of her name, though: “Lallie’s out of a book named Lallie Rook, an’ I was born on the Joy steamboat line going to Boston.” I had wondered where the name came from.

A character that appears in the movie, Ossian “Osh” Popham, is also in the book, although instead of being the store owner, he’s a local handyman who helps the family get the house in order. His children, also characters in the movie, are in the book, too, although I didn’t like the way the book described his daughter, Lallie Joy. It says that “she was fairly good at any kind of housework not demanding brains” and that she “was in a perpetual state of coma,” in case you didn’t understand that she’s basically stupid. I always hate it when stories make a character intentionally stupid. I did appreciate her explanation of her name, though: “Lallie’s out of a book named Lallie Rook, an’ I was born on the Joy steamboat line going to Boston.” I had wondered where the name came from.

When Lemuel tells the Careys that they can stay in the house for as long as they like, unless his son Tom wants the house, Nancy begins thinking of Tom as a possible threat to her family’s happiness. (She thinks of him as “

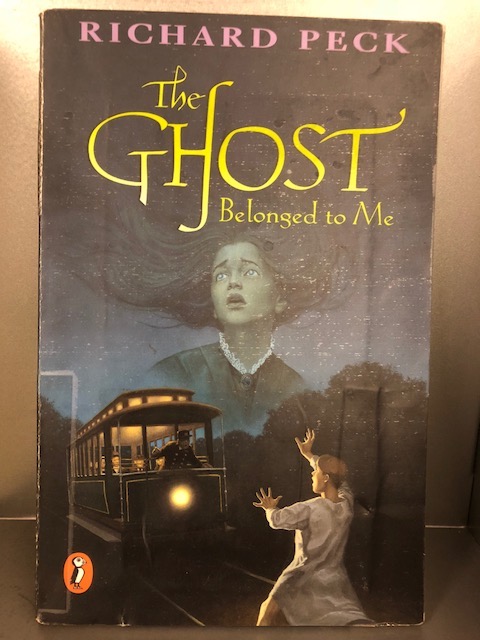

When Lemuel tells the Careys that they can stay in the house for as long as they like, unless his son Tom wants the house, Nancy begins thinking of Tom as a possible threat to her family’s happiness. (She thinks of him as “ Blossom Culp and the Sleep of Death by Richard Peck, 1986.

Blossom Culp and the Sleep of Death by Richard Peck, 1986. The Dreadful Future of Blossom Culp by Richard Peck, 1983.

The Dreadful Future of Blossom Culp by Richard Peck, 1983.