Little House on the Prairie Series

Little House in the Big Woods by Laura Ingalls Wilder, 1932.

The story begins “60 years ago”, in a little house in the woods in Wisconsin, where a little girl named Laura lives with her parents and her two sisters, Mary and Carrie. Mary is older than Laura, and Carrie is younger. Their father hunts for meat for the family in the woods, and although Laura worries about the wolves in the woods, she and her family are safe in their little house.

Much of the family’s time is occupied with getting and preserving food. Food preservation is important because not every hunting trip is successful, and they need to make sure that they make the best use of every animal they get, as well as dairy products and produce. Laura and Carrie like to play among the food being stored in the attic. One of their favorite chores is helping their mother mold butter into shape with their butter mold, and often, the highlight of their day is getting something special to eat.

The story begins in winter, and Christmas is coming. The girls help their mother to prepare some special foods and treats, like apple pie and vinegar pie. They make candy by pouring a molasses syrup over snow to freeze it. The girls’ aunt, uncle, and cousins come to visit, staying overnight. The children have fun playing in the snow, making what they call “pictures” by throwing themselves down in the snow and seeing what type of shapes they can make with their bodies. The family has a feast, during which the children are not allowed to talk because “children should be seen and not heard”, but they don’t really mind because the food is really good, and they can have as much as they like. The children believe in Santa, and they are happy with the simple presents they receive: a pair of red mittens and a peppermint stick each.

Laura also receives a very special present: her first real rag doll. Her older sister already has a rag doll, but up to this point, Laura didn’t. Her only doll was made from a corn cob. Children of their time don’t get many presents, and the youngest children don’t get any at all or only have improvised toys. The other children aren’t angry or jealous because Laura has received this extra present because she is younger than they are. Only the babies in the family are younger than Laura, and the older chidren know that Laura didn’t already have a doll, like they do. Laura isn’t being favored; it’s just that she is now old enough to get this kind of present.

Although the family is safe when they’re in their log cabin, there is a genuine risk of attack from wild animals when they’re outside. Members of the family talk about close encounters they or other people had with panthers or bears. Laura’s Pa has a humorous encounter with a tree stump that he mistakes for a bear in the snow, while Ma actually slaps a bear because she mistook it for the family cow.

As the seasons change, the family activities change. They help relatives make maple syrup, and they have a dance. The girls have their first trip to town with their parents. Pa gathers honey, and Ma makes straw hats. Pa helps a relative with his harvest, and a cousin who plays mean tricks instead of helping gets his comeuppance.

I couldn’t find a copy of this book to read online, probably because of the racial language in the story, but there are shorter books on Internet Archive based on individual incidents in this story, like the winter and Christmas scenes. I thought those were the best parts of the story anyway. I would recommend those shorter books and picture books over the original for young children.

My Reaction

Things I Liked and Didn’t Like

It’s been a long time since I first read this book, and honestly, I didn’t like it as much as I did the first time. I remembered kind of liking it when I was a teen. I can’t remember exactly how old I was the first time I read it, I might have been a young teen or tween, but I know I didn’t read Little House on the Prairie books as a young child. My mother wasn’t really into the series herself, so she didn’t read them to me or recommend them much. (She preferred Nancy Drew, and really, so did I.) I know I lost interest in the series after reading only one or two more books because it seemed like that poor family was always getting sick everywhere they moved, and I found that depressing. This book series is one of the reasons why I don’t believe that exercise and organic food by themselves keep a person from being sick. This family had both, and it never helped them. During the course of the series, they catch everything from malaria to scarlet fever or meningoencephalitis, whichever it was that eventually made Mary go blind. It’s like all of the diseases my characters died from in the Oregon Trail computer game but in book form. Come to think of it, people on the Oregon Trail were also exercising and eating organic, and I’ve seen the real tombstones of pioneer children. I believe in sanitation and vaccinations.

As an adult, I found much of the first half this particular book boring or frustrating. That’s surprising because I usually like books with details about life in the past, and many of the details in this particular book echo stories passed down in my own family. (I also had ancestors with strict traditions about not working on Sundays, and they also ate cold meals on Sundays because they had to do all the Sunday cooking the day before.) I found some of the early parts of this story grating. The main reason is that this book is not actually a single story. There is no real, over-arching plot. It’s basically a collection of episodic reminiscences and family stories. I found some of them interesting, but not the early parts.

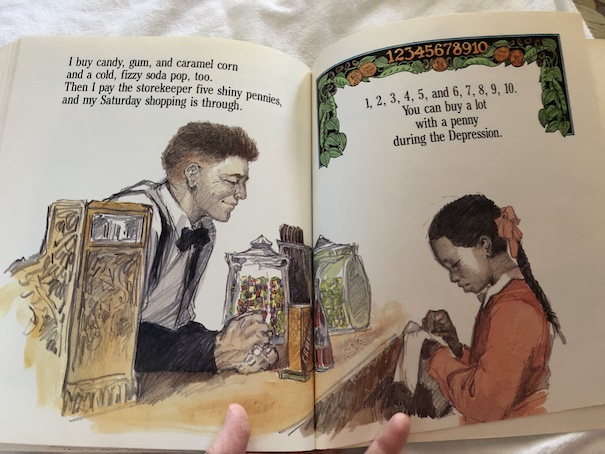

The book isn’t bad because the writing quality is pretty good, but in the first part of the book, there are long descriptions of hunting and food. I hated the descriptions of how they processed animals they hunted and butchered. I’m sure they’re true-to-life, but I’m the squeamish type. The parts where they talk about foods they like are better. They have kind of a cozy feel, with homemade meals and goodies that have kind of a nostalgic feel. However, I’m not that much of a foodie, and I’m not into “food porn” or long detailed descriptions of things other people are eating. There are limits to how much of that I can take before I start wanting more plot to happen. I think food descriptions are good when used to add color and atmosphere to a story, but it’s too much when they start turning into the story itself. Ideally, a good food description in the book will make me think of a story I liked the next time I eat that particular food. When it’s too overwhelming, there isn’t much of a story to be transported to. Part of the reason why Laura dwells on the subject of food is that this family has to struggle and work hard to get it. It’s not always guaranteed, and when there is something extra, there’s reason for celebration. They are poor, and treats are rare. I think that part of the reason why this book was so popular during the 1930s, when it was first published, was that many other children were growing up in a similar situation during the Great Depression.

When there is more action in the first part story, it’s typically that someone has a close encounter with a dangerous wild animal, like a panther or a bear. Most of this isn’t something that little Laura witnesses directly, but people will tell her stories about family members who had this happen to them. It happens repeatedly throughout the book. One really exciting encounter with a wild animal who wants to eat someone makes for a good adventure story, but when it happens repeatedly, the novelty goes out of it. It starts to become more like, “Oh, another animal attack incident story. Everybody’s got one.” Ma slapping the bear was something special, though. After the other descriptions of animal attacks, Pa’s mistaking a stump for a bear and Ma actually slapping a real bear felt like the punchline of a joke.

People in Laura’s family carry guns with them whenever they go out both for hunting purposes and because they are living in a real wilderness full of dangerous animals, and there is always a real possibility that they might have to defend themselves from a bear, panther, or wolf. They also eat bear when they can get one, and Laura likes the way it tastes. One of the chores that the kids find fun is when they help their father make his own bullets using molten lead in a bullet mold. I actually know someone who does this in modern times. Some modern gun hobbyists do, but I’m not into guns myself, so I didn’t find that as interesting as other types of home crafts. As the book continued and the seasons changed, there was more variety in activities for the family, and I started getting more interested.

The books in this series are semi-autobiographical, based on the real life and childhood of the author, Laura Ingalls Wilder. Laura Ingalls Wilder is actually the Laura from the book. That’s partly why the book isn’t structured liked a story so much as a collection of reminiscences, because this is just about what she remembers from her early life and family. I appreciated some of the small details of daily life, like the log cabin where the family lives, the butter mold with the strawberry shape, the trundle bed where the girls sleep, the lanterns they use for lighting, the family’s Sunday traditions, how the ladies prepared for their dance, and how they made maple syrup and straw hats. The parts of the story that I didn’t like so well were the parts where she goes on about the parts of life in the past that interest me the least. I don’t like hunting, I have no interest in guns, I don’t like hearing about butchering animals, and I’m not the kind of person who gets excited about animal attacks. (I never liked watching them on National Geographic, and I refuse to watch Shark Week or anything like it.) The parts I liked better were about using items that people just don’t use anymore and often don’t even have in their homes and the things the family did for fun and entertainment or celebrating holidays.

One of best scenes in the book, which is probably many people’s favorite, is the Christmas episode. It’s charming how Laura and her family make candy by pouring molasses syrup over snow. People can still do this today if they want to try an old-fashioned treat. It’s also heart-warming that they spend Christmas with visiting relatives, playing outside in the snow and enjoying a few simple presents, mostly handmade. They take great pleasure in simple activities and small presents because much of the rest of their lives were about chores and basic survival, and special treats and presents of any kind were rare. I thought about this book during the covid pandemic, when many people couldn’t safely visit with family or friends for Christmas. This is just one household of people, with just a few relatives visiting for a day, enjoying a few simple pleasures and homemade food and fun. It can be possible to enjoy very simple, homemade activities if you take the time to fully appreciate them and really throw yourself into making the most of them. The Christmas scene was the one that really stayed with me from my first reading when I was young, and it was the main reason why I wanted to read it again. I forgot most of the rest of the book.

Racial Language Issues

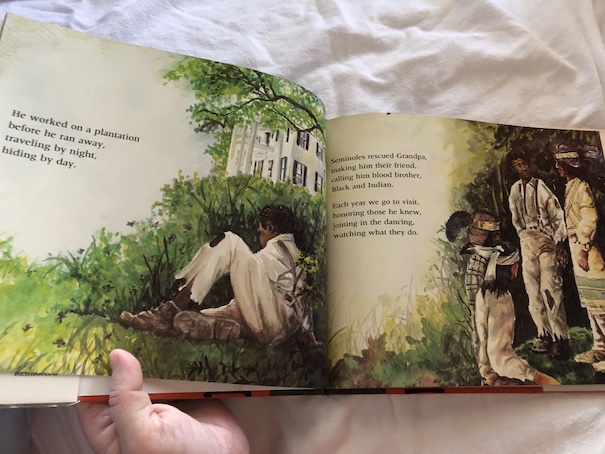

One thing that many people find distasteful about the Little House on the Prairie books these days is that books in the series have inappropriate racial language. This sort of thing went completely over my head when I was a kid because I didn’t know what some of these words meant, but it really jumps out at me now. At one point in the story, Laura’s father plays his fiddle and sings a folk song called Uncle Ned (that link is to a page from Missouri State University with words and music), which is about a black man who dies and uses the word “darkey” repeatedly. To be completely honest, I listened to the entire recording of this song, and I have no idea why anybody would like it. It’s not the only song Pa sings in the story about someone dying, and I can’t figure out why he thinks any songs like that are fun. They just sound depressing to me. But, Uncle Ned stands out from the other songs because of the racial slur.

I want to stress that it definitely is a slur. “Darkey” was not a polite term even during the time the story was set. People said it, but it was rude and insulting slang, not a word for polite conversation. Black people did have feelings about racial terms, and there were terms that were preferred and polite and terms that were considered demeaning and insulted and were known to be deliberately condescending. This particular term belongs to the second category. Black people weren’t always able to openly express their real feelings about the rude terms because of threatened violence for anything they might say, but their inability to speak openly about the issue doesn’t change the reality of the issue. There were 19th century white people who were well aware of what terms were polite and which were impolite, and they made active efforts to teach children to speak politely, such as the editors of this 19th century children’s magazine and Rev. Jacob Abbott, author of the Stories of Rainbow and Lucky (1859-1860), among other children’s books. Both of those sources are older than Laura Ingalls Wilder, pre-Civil War. Abbott made it a point to include a conversation between a grandfather and grandson in one of his Rainbow and Lucky stories to teach children the polite way to address black people of their time (“black” was one of the less preferred terms until the Civil Rights era, when people wanted to distance themselves from older racial terms and their accompanying emotional baggage, but the advice to care about others’ feelings and what they want to be called still holds true):

“I don’t know who they are, grandfather,” said he, after gazing at Handie and Rainbow a moment intently. “One of them is a black fellow.”

“Call him a colored fellow, Jerry,” said the old man. “They all like to be called colored people, and not black people. Every man a right to be called by whatever name he likes best himself.”

“But this is a boy,” replied Jerry.

“The same rule holds good in respect to boys,” added the old man. “Never call a boy by any name you think he don’t like; it only makes ill blood.”

True politeness requires consideration for others’ feelings, not denial of them, which would be the exact opposite of politeness by literal definition. Politeness is about avoiding what would offend others and emphasizing behaviors others find pleasant, not about doing only what pleases oneself or choosing to take personal offense at the idea of considering another’s feelings.

So, what’s the deal with Pa Ingalls? If other white adults of this era cared and tried to teach their children to care, why doesn’t he? Some people might point out that he’s just singing a song and that he didn’t write the song, which is true. In this particular instance, he’s effectively quoting someone else. That being said, this is just the first instance of questionable racial terms and attitudes in this series, and some of the later ones are worse. After thinking it over, I think what it comes down to is that the Ingalls family has little need to consider how people of other races feel specifically because of the way they live. Most of the time, there are simply no “others” in their lives to consider.

Nobody thinks anything of this type of language in the story or comments on it because, remember, this family lives in a log cabin in the woods with no close neighbors. They rarely go to town, and when they visit with other people, it’s usually other relatives, like the children’s aunt and uncle or grandparents. What I’m saying is that, when you live alone much of the time or surrounded only by people like you, especially close relatives, you don’t have to put much energy or thought into how to live with other people. The Ingalls family doesn’t have to think about any of this, so they just don’t think about any of this. But, when it comes right down to it, that’s certainly not the kind of life I’ve lived or the kind of life modern 21st century children live.

Since my first encounter with this book, I grew up in a city, in multicultural society full of people to interact with every day, and I got a higher education with a heavy focus on cultural issues. Some of the words in this book went over my head the first time, but I grew up. This book did not grow with me, and the racial language is one of the parts that not only doesn’t hold up but feels worse when you’re older and know better. This is not a book that has greater depth and provides more insight when you go back and read it as an adult with more life experience, as some children’s books do. Instead, it brings out some uncomfortable realizations about characters you liked before and the lives they live.

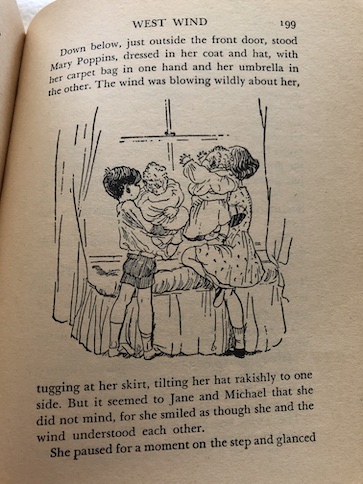

I’ve read that some newer printings of these books have changed the problematic parts, which is actually very common with older classic children’s books that are still in print. The same thing was done to old Stratemeyer Syndicate books like the Bobbsey Twins, Mary Poppins books, and various books by Enid Blyton. I was surprised when I found out what some of the original editions of those books were like. However, I haven’t seen a new copy of any of the Little House on the Prairie books to know how much has changed. There are parts of this series that I remembered from reading them the first time, mostly the Christmas scenes, but I’m just not really into this series. There are others I like better. Overall, I really prefer the Grandma’s Attic series to the Little House on the Prairie series because it also has details of daily life in the past, but I feel like it has more variety and warm humor to the stories in those books, and there are no inappropriate racial terms. My own grandmother grew up on a farm in Indiana, and she specifically recommended the Grandma’s Attic series to me, saying that it reminded her of her youth. She never mentioned or recommended Little House on the Prairie books, so I suppose she wasn’t as into those, either.