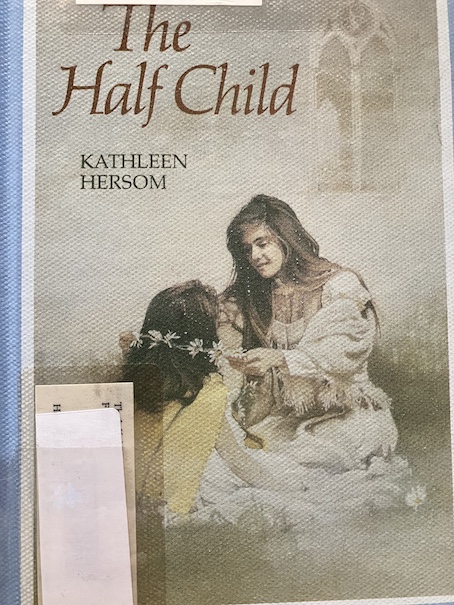

The Half Child by Kathleen Hersom, 1989.

Lucy Emerson (Lucy Watson after her marriage) and her family live in an English village in the 17th century. As an elderly woman in her early 60s, she looks back on her sister, Sarah. She has actually had two sisters named Sarah, but it’s her first sister Sarah that she thinks of.

Little Sarah was always a strange child. From when she was very small, she would do odd things, like rocking back and forth while singing odd little wordless songs and being very clumsy. She could never talk clearly, and most people couldn’t really understand her. Because she is abnormal, she is quickly labeled as a “changeling” – a fairy baby substituted for a regular human child. Those who don’t call her a changeling call her a “half-wit.” Only Lucy really values Sarah, whether she’s a little human child or a fairy child, and she tries hard to understand her and take care of her. What Sarah likes best are the little “stone dollies” – small statues of praying children – in the local church, and she always asks Lucy to take her there to see them.

Lucy and Sarah’s mother is often harsh with Sarah out of frustration because she’s difficult to understand and difficult to deal with. Some people in the community think that she should be even more harsh with Sarah than she is because, if she really is a changeling, the fairies or Little People might snatch her back if she isn’t being treated well, being beaten or starved. Their Granny believes that Sarah is a changeling, and she implies it often, comparing a changeling child to a cuckoo’s egg, substituted in the next for another’s bird’s egg. However, their mother never refers to Sarah as a changeling and doesn’t seem to believe that Sarah isn’t really her daughter.

Then, one day, they can’t find Sarah. It seems like she’s wandered off by herself. Lucy looks in the church to see of Sarah went there to look at the “stone dollies.” Sarah isn’t there, but one of the dollies has the daisy chain that Lucy made for Sarah. According to superstition, a daisy chain helps to protect a child from the fairies, and Lucy thinks that, without it, maybe the fairies did carry Sarah away. On the other hand, maybe Sarah fell in the river, and it carried her away. Worried, Lucy desperately searches the village for Sarah, until one woman says that she saw Sarah in the churchyard. She would have walked Sarah home, but Sarah didn’t want to come with her, so she came to get Lucy to take her. Lucy hurries back to the churchyard and finds Sarah there, waiting for her. Lucy demands to know what Sarah has been doing, and she says that she’s been playing with the “little people.” Fearing that Sarah is talking about the fairies, Lucy demands to know if she’s seen them before or had anything to eat from them, but Sarah just says, “Not telling.” Lucy considers that maybe Sarah meant something other than fairies when she said, “little people.” Maybe Sarah just met some other young children, or maybe she was talking about playing with the stone dollies again.

One day, Lucy leaves Sarah at home with their mother when she goes to visit their older sister, Martha, who is working at a farm near a neighboring town. Lucy’s mother tells her that Sarah should stay home because it’s such a long walk to the farm, and Sarah is too little to handle it. When Lucy returns home from the visit, she discovers that something disastrous has happened while she was away. Lucy’s mother, who was pregnant and due to give birth in another month or so, accidentally tripped over Sarah in some way and fall, bringing on the birth of the baby too soon. A neighbor who came to borrow some salt found her and called the midwife to come and tend to her. The baby is safely delivered and survives, but Lucy’s mother is in bad condition.

While everyone was busy attending to the mother, little Sarah apparently ran away from the house and disappeared. Lucy is too worried about her mother and the baby at first to leave the house and go looking for Sarah, although she sends her brother to ask the neighbors if they’ve seen her. Her uncle promises to look for her in the countryside and to send out criers to the neighboring towns if she isn’t found. However, the town is also disrupted that day by soldiers who vandalize the town’s church! Later, Lucy goes to look for Sarah in her usual favorite spots, but she doesn’t find her. When Lucy returns home, her brother tells her that their mother has died.

Their father says that their mother’s last wish was that this new baby girl will be named Sarah. Lucy is shocked because she is sure that the sister named she already has is still out there somewhere, lost. Lucy’s father isn’t so sure. He seems to suspect that the rumors were right, that Sarah was always a changeling, that maybe she has gone back to the fairies now, and that this new baby may be the Sarah they were always meant to have. At least, Lucy’s mother seemed to believe that when she told him that this new baby was to be named Sarah. Lucy never thought that her father believed the changeling stories, but he privately admits to Lucy that he doesn’t really know what to think. None of it makes sense to Lucy because, after all, her mother was pregnant with this new baby while Sarah was still at home with them. If the first Sarah was taken away and the “real” Sarah left her in place, surely there would be two babies now – the “real” Sarah plus this other new sister. As it is, there’s only one baby and one missing sister. Lucy father says that if Sarah returns before the baby’s christening, they will choose another name for the baby, but if she’s still gone, she is probably gone for good, and the baby will be named Sarah.

Sarah is not found by the time the baby is christened, so the new baby becomes the “new” Sarah. Sarah’s father and sister, Martha, try to console Lucy about the loss of the first Sarah, saying that it might be for the best and that Lucy’s life will be easier now because Sarah was too wild, too strange, and too difficult to care for. Lucy feels even worse then they say that because, although Sarah was difficult to look after, Lucy truly loved her and didn’t think of her as a burden. Lucy takes care of her new sister for a couple of years, never giving up hope that she will find the first Sarah or at least learn what happened to her. When Lucy’s father decides to remarry, Lucy goes to work on the farm where Martha is working, leaving the new Sarah to be cared for by their stepmother.

It’s only after Lucy goes to work on the farm that she eventually meets someone who is able to tell her at least some of what happened to the first Sarah after she was lost.

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive.

My Reaction and Some Spoilers

I first read this story as a young teen in middle school, and I found it fascinating for the historical and folkloric connections. This story takes place over a period of years. The year when the older Lucy reflects on her sister Sarah is 1700. During the year that the first Sarah disappeared, Lucy is talking to someone else, and they mention the Roundheads and that the king was executed the year before, so they are referring to the execution of Charles I in 1649, putting the year of that conversation at 1650. Most of the book is set around the middle of the 17th century.

In real life, there were stories about changelings, fairy children substituted for human children as infants, and stories like this seem to have been used to explain human children born with deformities or disabilities of various kinds. Modern people might recognize that young Sarah was born with some kind of developmental disability, which is why she’s not like her siblings, but people in the past didn’t have as much ability to diagnose or understand people who were born “different” from others. They couldn’t understand how children with disabilities could be born to apparently healthy parents, especially ones who had produced other healthy children, so they explained it by saying that those children were not the “real” children but substitutes left by the fairies in exchange for the healthy human children, like a cuckoo lays its eggs in the nests of other birds, to be raised and cared for by them. In the story, Lucy’s grandmother makes the comparison between Sarah and the cuckoo bird, although Lucy is very upset by that description.

During the course of the story, Lucy, as the one who seems to understand Sarah the best and love her the most, struggles to find her missing sister and learn what happened to her. At various times, she also struggles to reconcile what other people tell her about Sarah being a changeling or being taken away by fairies with her own love for Sarah as her sister, a real sister and not just a changeling, and her own worries about the more mundane tragedies that can befall a lost and neglected child. There are times when Lucy finds it difficult to ignore the superstitions of the people who raised her, and she finds herself at least halfway believing in fairies and that the girl she loves as a sister is in danger from them. While Sarah is with her, she makes daisy chains for her to wear as a precaution against the fairies taking her, although those who seem to most believe that Sarah is a changeling would be happy to see her reclaimed by fairies in the hopes of getting the “real” child back.

When their dying mother insists that the new baby girl be named Sarah, Lucy is heart-broken, realizing that her mother believes that Sarah was a changeling all along and that this new baby is the “real” daughter that Sarah should have been. However, to Lucy, who always loved the first Sarah, this new baby is the imposter Sarah, the “new” Sarah, taking the place of the Sarah she has loved and cared for. She never feels the same way about the new Sarah as she did for the first Sarah.

What always interested me about the story since I read it when I was young was how it demonstrates that real phenomena and the more inexplicable parts of human nature are part of the basis behind folklore. All through the book, people refer to children like the first Sarah as being “changelings” because they simply don’t understand why these children are the way they are, but the superstition is ultimately less about people genuinely trying to understand something and more finding a way of taking out their emotions on the “problem” or finding an excuse for not really dealing with it. Beyond the adults simply failing to understand children like Sarah and help their development to the best of their ability, their superstitions lead some of them to be deliberately cruel to children like her in the hopes that the fairies will decide to reclaim them. When a child like that runs away or is lost and never recovered, the adults tell themselves that the child was simply taken by the fairies, apparently both as an excuse to stop looking for a child they don’t know how to handle and also to soothe themselves that they don’t have to worry about her anymore because she is being taken care of by her “real” supernatural family. Whether they really believe that’s what is happening on an intellectual level or not, if they can convince themselves and others that it’s true on an emotional level, then they’re basically letting themselves off the hook and getting rid of an unwanted responsibility without guilt, which sounds a lot less noble than trying to understand and help make the situation better. I think that attitude comes from the sense that these people didn’t think it was even possible for them to understand or deal with the situation. From that attitude, the notion of the “problem child” magically vanishing would be appealing.

It’s sad because, as readers realize, that is not actually the case. Sarah’s disappearance isn’t magical. What Lucy learns about Sarah after the time she disappeared contradicts that idea because she did almost die but was rescued by a kind stranger who happened to be in the right place to find her. Sarah’s eventual whereabouts are unknown at the end of the story because she seems to have wandered off when her caretaker died or shortly before that. Until the very end of the story, elderly Lucy thinks that Sarah is probably dead, having spent some time wandering wild somewhere, but the fact that she never learns for sure leaves it open that Sarah could be alive or for Lucy to convince herself that maybe she finally got Sarah back in the end. When another child, who is very like Sarah, is born into the family, elderly Lucy finds herself wondering again about changelings. Is this new child just another unfortunate child who happened to inherit the developmental disability that Sarah had, or has the original Sarah managed to come back to Lucy in another form? They are so much alike that Lucy begins speaking to her as Sarah, and the new child answers just like Sarah always did, leaving the situation ambiguous in Lucy’s mind.

Although Lucy is ambivalent in her feelings at the end of the story, modern readers will likely side with the more scientific explanation of heredity and genes that sometimes reappear in later generations, producing lookalikes and people with similar health conditions. However, I think that the author did a good job of depicting the uncertainty that affects people confronted by situations and conditions they have no capacity to understand. The people of Lucy’s time did not understand what causes developmental disabilities. Because they needed to come up with an explanation for something they couldn’t understand, they developed the superstition about children like Sarah not being fully human or being substitutes for the “real” children, who were abducted by supernatural beings. Lucy finds herself torn between her own sense that Sarah is her real, human sister and that there must be more logical explanations and her own inability to understand what ultimately happened to her sister.

The book is a little sad because readers can recognize that, with better understanding and support, the original Sarah would have lived a much happier life and that Lucy (and others who appear later in the story) wanted to give her the support she needed but just didn’t know how. At the end of the book, Lucy reflects that times have changed since she was younger. Most people don’t believe in changelings and other old superstitions in 1700, not as much as they did in 1650. The Puritans, in particular, reject all such ideas as “pagan superstitions.” Society seems to be moving more in the direction of rationalism. Lucy says, “So there are plenty boasting nowadays that they cannot believe in such hocus-pocus, and that they have what they call a scientific reason for explaining any strange happenings that occur, instead of blaming the fairies, duergars or witches even. Though much that some call scientific I would say was just plain common sense.”

Even though Lucy generally believes in the rational explanations for what likely happened to the first Sarah, she experiences some doubt again at the end of the story, when she’s confronted with the young relative who looks so much like her. I liked the way the story ends on a slightly ambiguous note, with Lucy reconsidering whether or not Sarah was a changeling and if she has come back to her in another form. Modern readers know that’s not likely, but it does speak to the lifelong uncertainty that Lucy has lived with and the element of uncertainty that often surrounds the human experience in general. Even in modern times, there are many things that we don’t fully understand. In the 21st century, we’re more likely to accept the idea that, just because we don’t know the explanation for something doesn’t mean that there is no explanation that humans can understand but that we just don’t understand it yet. Still, that feeling that there are things beyond our mental grasp still appeals to the human imagination. If Lucy wants to believe that she has found Sarah again, after a fashion, it might give her some peace. For me, though, I just feel a little reassured that this member of the next generation might get more of the love, attention, and support that Sarah always needed, at least from Lucy, and less of the superstition surrounding her condition.

In the section at the back of the book about the author, it says that Kathleen Hersom used to volunteer at a hospital working with mentally disabled children. She was inspired to write this story both because of that experience and because of her interest in folklore.