Stories of Rainbow and Lucky

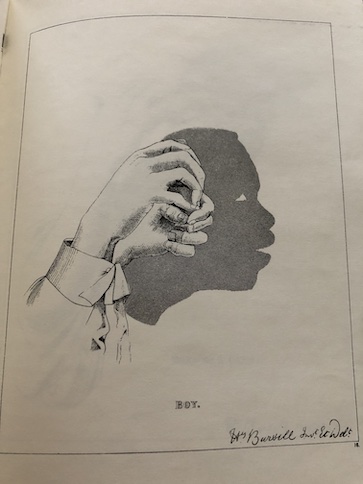

Handie by Jacob Abbott, 1859.

I’ve been wanting to cover this series for some time. It’s an unusual series from the mid-19th century, written on the eve of the American Civil War, by a white author with a young black hero. Rainbow is a teenage black boy who, in this first installment of the series, is hired by a young carpenter, who is only a few years older than he is, to help him with a job in another town. The entire series is really one long story, like a mini-series, and each book is an installment in the story.

This first book focuses mostly on the young, white carpenter Handie Level, why he needs to take this job in another town, and why he decides to hire Rainbow to come with him. The rest of the series follows the two young men, particularly Rainbow, through their adventures, learning life lessons, even dealing with difficult topics like racism. (Lucky is a horse, and Lucky enters the story later.) It’s unusual for this time period for black people to be the heroes of books and for topics like racism to be discussed directly. It’s also important to point out that our black hero is not a slave, he is not enslaved at any point in the series, and the series has a happy ending for him. People don’t always treat him right, but he does have friends and allies, and he manages to deal with the adversity he faces and builds a future for himself.

I want to explain a little more about the background of this book, but it helps to know a couple of things before you begin. First, the author was a minister who had written other books and series for children, Jacob Abbott. He had a strong interest in human nature and the details of everyday life, so his books are interesting for students of history. He explains some of the details of 19th century life that other people of his time might have taken for granted, and he also liked to explain the reasons why his characters behave as they do in the stories, exploring their personalities and motivations. Second, as part of the author’s character studies and also just for the fun of it, he made many of his character names puns that offer hints to the characters’ roles or personalities, so keep an eye out for that when new characters are introduced. Some of these pun name or nicknames are obvious, but others require a little explanation. Rainbow’s employer, Handie Level, is a level-headed carpenter who’s good with his hands, so the meaning of his name is pretty straight-forward. “Rainbow” is the nickname of our black hero, not his real name. We are never told what his real name is. He apparently has one, but even the author/narrator of the story admits that he’s not sure what it is. He is nicknamed “Rainbow” because he is “colored”, and that may require a little explanation.

During the course of the books, the author explains that “colored” was one of the more polite words used for African Americans during the mid-19th century. The author wanted to make his stories educational for children of his time, so there are points when characters discuss how to address African Americans politely, explaining which terms are acceptable and which are not acceptable. The basic rule that the author establishes of not referring to anybody by a name you think they wouldn’t want to be called still holds true today, no matter who you’re talking about. It’s important to consider other people’s feelings in how you describe them, and it’s good to teach children to notice and care about other people’s feelings. However, some of the polite racial terms the author recommends in the books sound out-of-date to people today and might leave modern readers wondering if they really are polite. The answer to the question is that they were considered polite at the time the book was written, but since then, some of the conventions regarding polite racial terms have changed.

A major shift in the terms used took place during the Civil Rights Movement, around 100 years after this series was written. People were intentionally trying to distance themselves from the emotional baggage associated with the racial terms that had been used previously, so instead of using “Negro” and “colored”, they began using “African American” as the formal term and “black” as the generic, informal term. This change in terms was meant to help create a sense of a fresh start at a time when cultural attitudes were changing. Because this book was written in the 19th century, the terms they use as the polite terms are the ones that were formerly used as the polite terms before that cultural shift. Even though most people wouldn’t speak like that anymore, you can still see the use of these terms occasionally, particularly in the names of organizations that were created prior to the shift in racial terms, like the United Negro College Fund (UNCF, founded 1944) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP, founded 1909). So, yes, “Rainbow” is a pun nickname because he is “colored” in the sense of the racial term. Apparently, the author was amused that the term made it sound like he was colorful, like a rainbow, although I think he is also a colorful personality.

The way a person speaks does offer hints to their background and character. Jacob Abbott had a fascination for analyzing the details of human behavior and the ways other people react to the other people around them them. He was aware of what was considered polite in his time and how the words people use affect other people. In these stories, he deliberately offers teachable moments to show child readers the differences between people who behave politely and considerately and the people who do not. As you go through the stories, feel free to study the characters and their behavior. The author meant for people to notice who these people are and why they do the things they do.

This book is easily available to read online in your browser through NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICAN CHILDREN & WHAT THEY READ, I’m going to do a detailed summary below. If you’d rather read it yourself before you read my review, you can go ahead, but some people might want to know in detail what they’d be getting into. There’s nothing here that I think would be racially offensive because it’s quite a gentle, sympathetic story. However, I can immediately see a couple of reasons why this book and its series hasn’t become a better-known children’s classic.

I wasn’t kidding when I said that the author goes into detail about some aspects of daily life and society in the 19th century. This story and its series, like others by the author, was meant to be education, so there’s a lot of teaching going on, both in the form of moral advice and general life lessons and in the specifics about how to handle money and negotiate business arrangements. It could still be interesting for someone studying daily life and social attitudes in the 19th century, but 21st century children might find it a bit dull. There’s more explanation than there is action and adventure, although I wasn’t bored while reading it, and there are a few interludes with character backstories, stories that the characters tell each other, and a strange dream Handie has. In the middle of the book, there’s kind of a touching story about a little boy and his widowed mother that I enjoyed, and it explains some of the reasons why the characters are in the situation they’re in.

Handie and Rainbow are the two main characters of the series, although most of this book focuses on Handie and his family. Their money troubles, an inheritance that Handie receives, and the arrangements that he makes on behalf of his family create the situation that causes Handie to hire Rainbow to help him with some work, which requires traveling to another town to manage his inheritance. The entire series tells the story of why they’re doing this, what happens to them on the journey to this new town, what they find there, and what it means for their futures, but it’s told in five installments. There are some spoilers at the end of this story to future stories in the series, which ruins some of the suspense, but this isn’t really meant as a suspense story. It’s a story about a couple of promising boys in the teenage years and what they do that sets them up for their future. One of them just happens to be black, and that’s something that figures more in the later stories in the series. This particular book has a few moments when the characters discuss race and the difficulties and discrimination that black people encounter in life, but it’s not a major focus. There is going to be outright racism in the stories, but this book mostly sets up the backstory of the characters and their situation.

The Story

Introducing the Level Family

Handie Level (his first name is short for Handerson, we are later told) is a poor boy who is reluctant to go to school because his clothes are so poor, but yet, he is eager to learn. Our narrator, an unnamed neighbor of the Level family, describes how Mr. Level has difficulty earning much money because he is not very strong and is physically deformed. He manages to earn sufficient money to keep himself, his wife, and their son in a basic way as a kind of repair man. He is very good at fixing things in his little workshop. However, he isn’t very good at managing the little money he has, and his wife isn’t very attentive about maintaining the house or the family’s clothes, making them look more poor than they actually are. It’s true that they don’t have much, but they could do better if they managed their resources better. It’s partly because they feel sorry for their poor state and not very hopeful about it improving that keeps them from striving to do better. In reality, they’re not that much worse off than their neighbors, but this feeling that they are is what keeps Handie from going to school and letting others see his poor state. Since he has not been to school so far and can’t read, Handie worries that he would be embarrassingly behind the other children if he tried to go.

One day, the kind neighbor/narrator sees Handie trying to teach himself to read. Wanting to help the boy, the kind neighbor gives him a book that will help him learn to read better than what he was trying to use. (The author of the story is probably inserting himself here as the friendly neighbor, especially because he also wrote other books about children’s education, children’s readers, and series of simple stories aimed at teaching children to read.) Handie is grateful and begins making more progress in his learning.

Handie also becomes more helpful to his parents as he grows older and takes an interest in learning to mend his own clothes. When his mother helps him to mend his clothes, he looks much better, and Handie praises his sewing ability. His mother is pleased at the praise, and we learn that her husband has been more in the habit of criticizing her efforts at everything rather than praising her. This constant criticism and lack of encouragement is another reason why she has not been trying harder to maintain the household and the appearances of her family. Handie’s praise encourages his mother, and with Handie’s help, she begins making more effort around the house and doing more mending. With his clothes looking nicer and his new ability to read, Handie feels more comfortable going to school, and he begins progressing in life.

As Handie grows up, he becomes more and more helpful to his parents, both around the house and in his father’s repair business. He begins taking jobs of his own and bringing in a little money. He helps his family improve their circumstances. Then, a new opportunity comes along. The man at the mill says that if Handie or his father can buy a horse and wagon, he would pay them good money to haul lumber for him. It’s a tempting offer, and it could be a job that Handie’s father could do that would pay him more than what he’s doing now, but Handie doesn’t know where they would get the money for the horse and wagon for either of them to use. Handie has been good about saving money from what he earns, but the amount they would need is a large sum.

When Handie finally talks to his father about the job offer, Mr. Level is upset. He has been very worried lately, and he reveals to Handie the reason why. Even though they own their house, there is a mortgage on it, and the mortgage holder (a lawyer in the village) is now insisting that the Levels pay him the full sum or the family will be turned out. Mr. Level doesn’t know where he will get the money to pay the full amount, and he doesn’t know where they can possibly live if they have to leave. Handie and his mother had no idea that Mr. Level had taken out a mortgage on the house, and they are distressed about the looming threat of eviction. The amount of money they would need to save their house is about the same as what it would take to buy a horse and wagon.

Introducing Solomon and Rainbow

While the Levels are debating about what they can do, the story flashes back a few years to a little boy named Solomon Roundly and the reason why Mr. Level is in such financial trouble. Solomon belongs to an industrious but poor family on the other side of the village from the Level family. The family is saving up to buy their own farm when Solomon’s father suddenly dies of an illness. The neighbors do their best to comfort Mrs. Roundly and young Solomon. Among the neighbors, there is a black lady and her 12-year-old son, who sometimes looks after young Solomon and plays with him or takes him fishing. (The book uses the term “colored” to describe the black boy and his mother because that was one of the more polite terms at the time. There is a point later in the series where the narrator specifically explains this.) The narrator says that he doesn’t remember the black boy’s real name because everyone has called him Rainbow for as long as anyone can remember, and they’re not even very certain whether he ever had another name.

One day, another local boy, called Josey Cameron, is accidentally injured when he tries to throw a stone into an apple tree to knock down an apple, and the stone comes back at him and hits him just above his eye. The boy cries with fright and pain, and Mrs. Roundly takes him inside and tends to the wound. Mrs. Roundly asks young Solomon to fetch Rainbow and see if Rainbow can take the injured boy home in his cart. Rainbow agrees to take Josey home, and Mrs. Roundly tells him to be sure to drop the boy off close to his house but not right in front of it and to let him walk the rest of the way so that his mother will see that he is not hurt too badly. If Mrs. Cameron sees them drop off her son right at the door, she might panic, thinking that he couldn’t walk at all. The reason why this little incident matters is that it happens shortly before Mr. Roundly dies, and it starts off a chain of events which explains Mr. Level’s mortgage.

Mr. Cameron is so grateful for Mrs. Roundly tending to his son’s wound and arranging for his ride home that he arranges a little present for the Roundly family. He is a daguerreotypist, meaning that he makes daguerreotypes, which is an early form of photography. Basically, he has a photography studio. He has Mr. Roundly pose for a daguerreotype as a reward to his family for their help. Mrs. Roundly is happy to see the picture of her husband when they receive it, but later, after her husband’s death, she finds it a painful reminder of the loss. Young Solomon, seeing his mother crying over the daguerreotype of his father, decides that if it makes her so unhappy to see it, maybe he should get rid of it.

Solomon takes the daguerreotype and goes to see Rainbow and asks him for a ride into the village. Rainbow is happy to give him a ride, but he asks him why he wants to go there. Solomon says he’s going there “on business”, which makes Rainbow laugh because Solomon is so little. Yet, Solomon insists that’s the case and tells Rainbow he’ll see it’s true when they get there.

On the way, Solomon insists that Rainbow tell him a story. Rainbow tells him the only one that he knows, a story about a man who killed a bear. (I find hunting stories rather gruesome, although I suppose 19th century children might have found this interlude thrilling.) Rainbow knows this story because his mother read it in an almanac once. Solomon asks Rainbow if he can read. Rainbow says he can’t read very well. His mother is too busy working to teach him, and it’s hard to learn on his own. He wishes he could go to school, but he says that the local people don’t like him to go. The other boys don’t want to sit near him, and people make trouble for him. Solomon wishes he could do something that would help, but he can’t think of anything.

In the village, Solomon asks Rainbow to take him to Mr. Cameron’s. When they get there, Solomon asks Mr. Cameron to make a daguerreotype of him, just like he did with his father and to replace his father’s daguerreotype in its case with his instead. Mr. Cameron is surprised at the request, especially since Solomon admits that his mother didn’t send him and he wants the picture for free, but he agrees to do it as a favor to the little boy. When Mr. Cameron makes the daguerreotype, Rainbow is standing behind Solomon, and he ends up in the picture as well. When Solomon sees it, he says that he didn’t mean Rainbow to be in the picture with him, but Mr. Cameron says that he doesn’t see a problem with it. In fact, he thinks that Rainbow’s presence really improves the picture and makes it “prettier.” Rainbow is surprised and flattered that Mr. Cameron, as a man of artistic sensibilities, thinks his face could make a picture more beautiful, and Solomon decides that the picture will serve his purpose as well with Rainbow in it.

When he gets home, Solomon puts his new daguerreotype in the place where his mother kept his father’s picture, and he puts his father’s picture away for safe-keeping. In the morning, his mother asks him about the new daguerreotype, and Solomon explains what he did. He says that he did it so that his mother would think of him now, and not his father, so she would be less sad. His mother agrees that’s a good thing to do, and she says that she doesn’t mind having Rainbow in the picture, either, because Rainbow has been so kind to Solomon.

Taking her son’s words to heart, Mrs. Roundly decides that she needs to start thinking of her son more and planning for the future again. She has some money that her husband left her, so she decides to see the lawyer in the village, Mr. James, about investing it on her son’s behalf, so her son will be able to buy a farm when he is grown. Mr. James is the same lawyer who holds the mortgage on the Levels’ property, and the money that Mr. Level borrowed from Mr. James is the money that Mrs. Roundly invested with him. Mr. Level was in debt at the time, and he promised to repay the loan with interest, using his house as collateral for the loan. The money that Mr. Level must repay is being managed by Mr. James, but it’s actually for young Solomon Roundly and his mother.

Mr. Level is not good at managing his money, he has been careless about making his payments on time, and because he didn’t tell Handie or his mother about it, there was no one else to remind him or make sure that he repaid the money he borrowed. Mr. James has already extended the loan and given Mr. Level chances to make payments, and Mr. Level hasn’t done it. Mr. James can’t in good conscience allow Mr. Level to not repay a widow and a fatherless boy the money he owes them because he knows they really need it. That’s why he’s insisting on payment now or he’ll take the house.

Handie’s Solution and Inheritance

When we return to the present after the flashback that explains the nature of the problem, Handie decides that the only thing to do is to see Mr. James himself and try to negotiate with him on behalf of his father and family. On his way, he meets Captain Early, who offers him a ride. Handie accepts and decides to ask Captain Early for advice about debts and mortgages. Because his father doesn’t understand much about money matters, Handie also doesn’t really understand mortgages or what the family’s options are.

Captain Early says that if the property that’s mortgaged is worth more than the current mortgage, it could be possible to take out a second mortgage from a different person and use it to pay off the first one, thus buying some time to fully repay the debt. Handie has some misgivings about this approach. Captain Early doesn’t think it would be hard to find another investor who would be willing to lend money in the hopes of earning interest on it, but Handie now knows that his father isn’t good at paying his debts or even the interest on them. Still, it’s the only sensible solution that anyone has proposed so far, so he decides to discuss the possibility with Mr. James.

When Handie goes to see Mr. James, they discuss the situation. Handie explains that he didn’t understand the state of his father’s finances before or he would have helped his father pay the debt, and Mr. James explains why he’s reluctant to allow them more time to pay. The reason why the matter is so pressing is that Mrs. Roundly and her son are living in a rented house, and the man who owns it is in need of money and wants to sell the property. If Mrs. Roundly gets her money back, she could buy the home herself, and she and her son could continue to live there. If she doesn’t, she will have to worry about where she and her son will live. To let the Levels continue living in their home while not repaying the debt would result in the Roundlys being evicted, and that would hardly be fair, since it was really their money in the beginning.

Handie agrees that it would be unjust to not repay the debt to the Roundlys and put their situation in danger, and he promises to try to work things out so he and his father can repay the money. Mr. James appreciates Handie’s practicality and understanding, and he says that it’s too bad that Handie is only 19 years old. If he was 21, he would be a legal adult, and he would be willing to invest in Handie himself to repay Handie’s father’s debt. The only reason why he can’t do it now is that, until Handie is a legal adult, his signature on any agreement wouldn’t be legally binding. Also, technically, under the law, Handie’s time and money don’t belong to him but to his father. Even if his father would allow him to have time and money to himself, everything that belongs to Handie, and even Handie himself, legally belongs to his father until he’s a legal adult.

As for what Captain Early said about taking out another mortgage or loan, even if Handie tried to arrange such a thing, any loan made to him would really, legally, be another loan to his father. Even if Handie gave his father the money to settle his debt or any other loan, there would be no guarantee that his father would actually use the money for that purpose. Legally, he can do what he wants with any money Handie gives him, even if Handie is the one who earned it, and even if he just wastes it instead of settling his debts. The truth is that Mr. James has already approached potential investors about making another loan to Mr. Level, but nobody wants to loan him money. Mr. Level has been complaining openly to people in the village about how unfair it is that he’s going to lose his house because he hasn’t repaid his loan. By doing all that complaining, he’s publicly outed himself as a bad debtor, and while people feel sorry for him, nobody wants to trust him with their money.

The situation looks hopeless to Handie. All he can think of is that his family will have to sell their house and move somewhere else. Because they can get more money from the sale of the house than they need to cover the debt, they could use that money to move somewhere else. Mr. James says that whoever buys the house might lease it back to them so they can continue to live there. They would just be paying rent to continue living in the house rather than paying the mortgage. It’s not a great solution, but it’s the only one open to them, and they will be left with some money from it. Handie explains the plan to his parents and to Mrs. Roundly, and they all agree to it.

It will take a couple of months to settle the sale of the house, so Handie tells his father that they must try to earn as much money as they can during that time. Mr. Level says that there’s no way they can earn enough to stop the sale of the house in that time, but Handie says that it doesn’t matter. Whatever money they can earn will help in setting them up with a place to live and improving their financial situation. Thinking again about the offer of a job delivering lumber, Handie decides that, rather than trying to buy a horse and wagon, maybe he could rent one. He does so, his father begins delivering lumber, and he and his father begin saving up money and paying down the debt.

Then, Mr. James sends Handie a message to come see him. Mr. James has received word that Handie’s uncle has died and left him a small farm called Three Pines. Because his uncle left the farm to Handie and not to his father, Mr. James is to hold it in trust for him until he is 22. (This is one year past the age of adulthood, but this is what his uncle specified.) There is money to go with the property, and as the executor of the estate, Mr. James is directed to use the money to fix up the property and rent it out to a tenant on Handie’s behalf until Handie is old enough to have it. The bequest would be helpful to Handie if he could use it immediately to pay his father’s debt, but there is still the issue that Handie is underage. While Mr. James can rent out the property and use the money on Handie’s behalf, it would be against the terms of the will to use the money to pay Handie’s father’s debts. While helping his father would indirectly help Handie, that’s not quite good enough to satisfy the terms of the uncle’s will.

What Mr. James suggests is that they follow the terms of the will that require him to use the money from the estate to hire someone to fix up the property, and to that end, he will hire Handie to do the work and pay him for it. It seems odd to be hired and paid to work on a house that’s technically his, but it’s a logical solution to the problem. Because of the lawyer’s strict interpretation of the will and his role in executing it, he doesn’t think it would be appropriate to give Handie an advance on his work so he can settle the debt right away, insisting that Handie must do the work before getting any money. Handie thinks he’s being too strict, which is not really in his best interests at the moment, but he doesn’t see how he can argue. The proposition that Mr. James makes for him would still allow him to earn more money than he is currently earning.

When he tells his parents about the bequest and Mr. James’s proposition, they are happy that Handie’s uncle left him something but disappointed that Mr. James is unwilling to use the situation to help them more immediately. Handie himself thinks that Mr. James should have made a little exception to the rules to give him an advance on the money, although he has a dream that night that gives him a different perspective. In his dream, a fairy argues with a clock, telling it that it would do some good for it to go a little faster sometimes and a little slower at others, according to people’s needs. The clock says that the trouble is that, if he speeds up for one person, he might go too fast for another person’s needs, and if he slows down too much, it might cause trouble for someone who needs time to go faster. Because changing the flow of time can hurt one person at the same time as it helps another, it’s better for him to just keep the correct time.

When he wakes up, Handie thinks about his weird dream and realizes that Mr. James is like the clock because he has to go strictly according to the rules, stable and predictable, to keep the situation steady for everyone. Sometimes, he might be tempted to do someone a favor by tilting the balance for them, but that can throw off other people who are also depending on him to follow the rules. Handie also considers the purpose behind his uncle’s will. His uncle and his father didn’t get along well, and his uncle was aware that his father was terrible at handling money. Handie himself has now become acquainted with his father’s lack of money sense and how it affects the rest of the family. He realizes that his uncle left his farm to Handie because he had heard that Handie was a practical boy and a good worker and would be more likely to take care of it. Therefore, he skipped over Handie’s father and left the farm directly to Handie, to be held in trust for him until he was a full adult to make sure that Handie’s father couldn’t use it for his own purposes or that Handie wouldn’t sacrifice something that would make a real difference to his future in his efforts to help his father. His uncle was planning for the long term, not the short term, something which Handie’s father never does but which Handie will have to learn to do if he wants a better future. Mr. James understands this thinking as well as Handie does, and that’s why he’s so adamant that they follow the terms of the will exactly.

When Handie speaks to Mr. James again, Mr. James reminds him that his father has a legal right to Handie’s time and anything that he earns through the use of his time. Time is a valuable resource, and Handie’s father owns his as a piece of property until Handie turns 21 years old. (In the book, Mr. James says, “You see the law requires that children should do something to reimburse to their parents the expense which they have caused them in bringing them up. … . They are required to remain a certain number of years to assist their fathers and mothers by working for them or with them. The time when they are finally free is when they are twenty-one years old.” This isn’t how society or the law would look at it in modern times, but I’ll have more to say about that later.) What Mr. James proposes to Handie is that he literally buy Handie’s time from his father, the remaining 2 years until Handie is 21 years old, for enough money to pay off the mortgage and give him plenty of extra money. If he does that, Handie will be working for Mr. James instead of his father for the next two years, and whatever he does or whatever he earns in that time would be for Mr. James. Handie agrees to this proposal because it would take care of his father’s money troubles.

However, Mr. James improves the offer by saying that Handie has the ability to buy his own time, in which case he will be working for himself, owning his own time and his own earnings. He has spoken to a gentleman in the village who is willing to establish a loan for Handie, which he can use to buy his time from his father. As long as Handie stays healthy and continues working during the next two years, he will have more than enough money to repay that loan. Handie asks what happens if he gets sick or dies. Mr. James says this arrangement will require him to take out life insurance as security, to repay the loan in case something happens to him. The farm Handie has waiting for him can also be security for the loan in case Handie is sick or injured, and Mr. James will also endorse the note, meaning that he will pay the debt if Handie is unable to do it. It’s suitable for Mr. James to do that as the trustee for Handie’s inheritance and more legally-binding because Handie is still a minor.

Handie explains this new proposal to his parents, and they all agree to it. Handie’s mother is worried that this arrangement will involve Handie leaving home, and she doesn’t know what they’ll do with out him, but Handie says it’s necessary for him to go to the farm he’s inherited and begin fixing it up. It will bring in more money in the long run, and he will come home to his parents when everything is order and the farm is ready to lease to a tenant until Handie is 21. When they accept the proposal, Mr. Level is able to pay off his mortgage and save his ownership of his house, and he has enough money left over to buy his own horse and wagon to use in his new delivery job. With the family’s fortunes looking much better, Handie prepares to go to farm and begin his work there.

Hiring Rainbow

So far, the story has mostly focused on Handie and his family, and we haven’t seen much of Rainbow since he was helping young Solomon, but this is a small village, and Handie does know who Rainbow is. This is the part of the story that establishes the relationship between Handie and Rainbow and how Handie decides to hire Rainbow to help him with the work on his new farm.

As Handie prepares to go to the farm, which is near another town, Mr. James talks to him about the arrangements he’s made to provide Handie with money to pay him the wages for working for his own estate and also to allow him to buy whatever supplies and hardware he will need for repairs around the farm. Because Mr. James won’t be there to oversee things directly, he’s made arrangements to send money to Handie through another lawyer who lives near the farm.

Handie is young, but he’s had experience as a carpenter. He can handle most of the work himself, but carpenters frequently need assistants to act as an extra pair of hands, helping them by holding boards in place or handing them tools as needed. Mr. James says that it would be appropriate for him to hire an assistant to help him, and he will provide money from the estate for that purpose. Since Handie doesn’t know anyone in this new town and wouldn’t know who to hire there, he decides that it would be better to bring an assistant with him from his village. He chooses Rainbow because, even though Rainbow is only 14 years old at this point, he’s big and strong for his age and is a good worker. He hasn’t had any training in carpentry at this point, but he doesn’t really need any experience to be an assistant. Rainbow is good at following instructions and is eager to do a good job and please people, and that’s more important.

Before he asks Rainbow if he wants the job, Handie tells Mr. James what he’s thinking to see if he thinks it’s a good idea. Mr. James says that, before he talks to Rainbow, he needs to decide how much money he would be willing to pay Rainbow out of the estate and what his accommodations would be while they’re in the other town. Handie proposes what he thinks would be a decent wage for an assistant and says that he will pay for Rainbow’s room and board. They will have to board somewhere in town until the farm is suitable for them to live in. Mr. James says that may be difficult because not every boarding house would be willing to have a “colored” tenant. Tenants in boarding houses all eat together at the same dining table, and not everyone will want to see at the same table as a black person. (This is just like Rainbow said that the other boys at school wouldn’t want to sit with him and would make trouble.) Handie is confident that he can find a place for them to board anyway, so Mr. James says that the plan sounds fine to him, as along as Rainbow agrees to it and Rainbow’s mother approves.

Handie goes to Rainbow’s house, but Rainbow’s mother says that he isn’t home because he’s working in Mrs. Roundly’s garden. Deciding that he should offer the job directly to Rainbow first before talking to his mother, Handie goes to find Rainbow.

Rainbow is working with young Solomon in the garden, and when they stop to rest, Rainbow says that he has a new story to tell, besides his usual bear one. A man read it to him recently out of a newspaper. It’s about a thief who was caught trying to steal money from a miser, and there’s an interlude in the main story where Rainbow tells this story. (Actually, it’s more like the thief was trying to get the miser’s money through extortion because he writes the miser a threatening note, demanding that he leave a sack of money in a particular place.) The miser’s sons set a trap for the thief and catch him.

As Rainbow finishes the story, Handie comes along and explains his job offer to Rainbow. It would require the two of them living in another town about 30 or 40 miles away for about 2 or 3 months. Feeling like he should tell Rainbow the hardest parts of the job, he says that the work will be physically rough, and he’s not sure exactly where they will be staying or what the “fare” (food) will be like, but he promises that, if Rainbow comes with him, he will pay him and that Rainbow will eat as well as he does himself. The physically hard parts of the job don’t sound appealing, but like most boys his age, Rainbow is adventurous, and the idea of going to another town, exact destination unknown, sounds exciting. Young Solomon thinks it sounds exciting, too, and he says he wants to go along. Solomon tries to prove to Handie how much he can lift, and Handie says that’s pretty impressive, and he would take him, if he could.

Turning serious, Handie asks Rainbow what he really thinks of the job offer. Rainbow says that he likes the idea, but he’s not sure what his mother will think and if she will be all right at home without him. Handie says that Rainbow can talk it over with his mother, and Rainbow persuades him to come along to see her and explain the job himself. At first, Handie is worried about the objections that Rainbow’s mother, Rose, might make, but actually, Rose is a sensible woman and sees that this is a good job offer for her son. She will miss him while he’s gone, but she doesn’t want him to miss out on this opportunity because of that. Since they’ve all agreed that Rainbow will have the job as Handie’s assistant, Handie and Rainbow begin their packing and preparations for the journey to Handie’s farm.

Even though Rainbow’s latest new story was one told to him by someone else, we are told at this point that Rainbow has made progress in learning to read and is now doing well enough at it to find it enjoyable rather than a chore. He is now able to read from the New Testament. His mother laments that he can’t write as well as he can read. She hasn’t been able to teach him more because she’s not that good at writing herself. Because Rainbow can’t write very well, he won’t be able to write letters to her while he’s away. Rainbow says that Handie could help him with that, and his mother tells him that, while Handie is his employer, Rainbow should call him Mr. Level. Handie is almost a grown man, and he is acting as grown man, doing professional work and being Rainbow’s employer and supervisor. (The book uses the term “master”, but they don’t mean it in the slave sense. This story was written and published before the Civil War, and slavery is legal during this period, but Rainbow is a free person, who is being employed at his own consent and paid a salary. The term “master in this case is more in the sense of a supervisor, someone who will be directing Rainbow’s work and overseeing the results.) Rose tells Rainbow that, if he has any problems on this job or if he does anything that causes a problem, he needs to be honest and tell Mr. Level (Handie) about it. If Handie knows what the problems are, he can help fix them, and hiding them would only make them worse. She has a little rhyme about it:

“Wrong declared

is half repaired;

while wrong concealed

is never healed.”

She also tells him that if anyone in this new town tries to give him a hard time or tease him because he is “colored”, he shouldn’t mind them. Rainbow says that’s very hard sometimes. Rose says that she understands but that fighting people wouldn’t do any good. He is likely to be outnumbered (that’s literally what it means to be a “minority”), so it’s better to use patience and show as little reaction as possible. They’re more likely to stop their teasing if he doesn’t give them the reaction they’re trying to provoke. Rose uses some local dogs as an example, pointing out how each of them responds to teasing. The one that just responds to teasing with a look of contempt doesn’t get teased as much. Rainbow points out that the dog who doesn’t react could probably head off further teasing if he put a scare into the teaser, but Rose says that only works if someone is big enough to put a scare to a teaser without actually hurting him and if the bully doesn’t have a bunch of confederates backing him up.

She further reminds Rainbow that the Gospel says, “that we must study to show kindness to those that do not show kindness to us.” She says that, while he’s away, she wants him to continue reading the New Testament and saying his prayers. She also makes a point that she wants him to think about the meaning of what he’s reading and have it in his mind that he will follow it in his life. She hopes that perhaps, during his time with Handie, Rainbow will improve his reading and writing ability and that Handie will help him. Before Rainbow leaves the village, he goes around to say goodbye to some friends and neighbors, and one of them gives him an inkstand and pens so he can write.

This installment of the series ends with Handie and Rainbow leaving on their journey to the new town, Southerton. We are told that, “Handie and Rainbow had a very pleasant ride, but they met with an accident on the road which led to a singular series of adventures. They, however, at last arrived at Southerton in safety, and spent two months there in a very agreeable and profitable manner.” This is kind of a spoiler for the next book in the series, which is all about their adventures on their journey. We know that they eventually arrive safely and proceed about their business, but the narrator promises to tell everything in more detail in the next volume. Actually, there are also spoilers for the rest of the series because we are also told that everything goes well with Handie’s farm, Mr. James is able to find a good tenant to rent it, and when Handie eventually returns home, he finds that his parents have been doing well and that Handie is able to repay the loan that bought his time from his father. There’s no suspense about any of that, whatever else happens in the following stories. In fact, the book says that the loan worked out so well for Handie that Rainbow thinks that he’d like to try a similar arrangement when he’s older. Handie says that, by that time, he might have the money to make him a loan himself.

My Reaction

I covered some of this above, but there are a few more things I’d like to talk about. Although the plot is a little slow and must of it focuses on how business deals work and the importance of hard work and prudent living, I actually thought it was an interesting book. What I found most interesting about it was the look at the daily lives and concerns of people in the mid-19th century.

I was a little surprised at the way the lawyer explained the laws concerning the ownership of Handie’s time and the laws about the obligations between children and parents. The relationships between children and parents and how they should behave toward each other, specifically what children owe to their parents are central to the story.

The parents in the story aren’t perfect people. Handie’s parents have some obvious flaws, particularly Handie’s father. Handie and his mother would have some justification for being upset with Mr. Level for getting their family into this financial hole and then depending on Handie to work out a solution, but they’re not really angry with him. Mr. Level is within his legal rights to use his money and theirs in whatever way he wants as the head of the household and Handie’s father, even though it’s obvious that he doesn’t really know what he’s doing. Nobody questions Mr. Level’s legal authority over his family’s financial affairs, although everyone knows he isn’t good at handling money, and they haven’t been able to get him to improve before. However, Mr. James and Handie recognize that whatever solution they work out together can’t violate Mr. Level’s rights to make decisions about his family’s affairs and must respect his authority over his son. What Mr. James suggests to Handie is a way of emancipating Handie’s financial affairs from his father’s while providing Mr. Level with generous compensation, which improves the circumstances of the entire family.

The part about children legally owing their parents some form of compensation for the costs of raising them surprised me. I’ve heard of that as a social convention, but I didn’t think there were actual laws about that. I’m not completely sure whether the author was right about that part or not because I had some trouble finding a source to verify that, but if anyone else knows the answer, feel free to comment below and tell us.

In modern times, there are laws about the care of children, and parents can be charged with neglect if they fail to provide certain necessities for their children, but I don’t think I’ve ever heard of a modern law about children giving compensation to their parents. After all, children can’t choose their parents like they can choose from among possible employers and negotiate their terms, so it’s not quite like entering into a business arrangement. I can see the logic of children helping the parents who raised them as part of family loyalty and affection, but the amount of care that family members show each other is difficult to codify because it’s hard to measure and put a price tag on human feelings. Emotional support is a natural and important part of family life, and it occurs to me that might be difficult to prove how much family members might have shown to each other. People value it, and it’s hard to say how much of that might be a service that they render to each other in a family.

It also occurs to me that individual families in the past may not have looked at their family through a legal lens, even if they had the legal means to do so. When Handie speaks to his parents about reorganizing their family’s financial affairs and about his new position, repairing the farm he inherited on behalf of his own estate, Handie tells his parents that, when he returns home from this job, he will live with them again but that he will pay them for his room and board. His mother tells him that paying to live with them won’t be necessary because he’s their son, but Handie insists because he will be working and earning money as an independent person, no longer a dependent of his father.

What that exchange tells me is that Handie’s mother doesn’t view him as an economic resource for their family. He’s just their son, and she loves him and would care for him, even if he couldn’t pay her for it. Their family isn’t overly concerned about money, they hardly even know how to manage the money they have, but they do understand family and human feeling. There are upsides to that because they are prepared to support each other just out of love and family loyalty, even when that would hurt their financial situation. The downside is that Handie has realized that, for their family’s future security, they’re going to have to be a little more strict about the financial aspects of the life they share together. While he is grateful for his parents’ feelings for him, he thinks that insisting on upholding his financial obligations to his parents will be more beneficial to them in the long run.

Maybe people in real life looked at it in a similar fashion, depending on their own family’s circumstances. Maybe there were times when they didn’t care that much about keeping track of each family member’s financial contributions and insisting on exact repayment from each other because their feelings for each other were in the balance and/or because some family members might not be in a position to compensate each other financially to the same degree because of health reasons or other issues. If the law is really as Mr. James says it is, the rules about children compensating their parents might have only been invoked in situations where there was some serious dysfunction in the family, like if a child resisted working or helping out at home at all, and the parents were desperate. If the parents were satisfied with their relationships with their children, they probably wouldn’t bother to keep strict accounting of their children’s monetary value or get petty about the laws with them. At least, that’s my theory. In the case of the story, the characters are in a pretty serious financial problem, with the threat of losing their home, so they seriously need to straighten out their finances according to the law.

So far, because most of the focus of the story is on the Levels’ financial woes and how they straighten out their affairs, the story hasn’t gone into detail about race relations. However, I already know that this becomes more of a central theme in later installments of the story. At this point, we know that Rainbow couldn’t go to school like Handie did because he wasn’t welcome there. Nobody uses the term “segregation”, but that’s basically what it is. Nobody explains the laws regarding this kind of segregation, so I’m not sure if there’s an official law about that for this village or not, but there seems to be at least a social convention about that.

Rainbow says that people have teased and taunted him about his race, although when he’s about to leave home with Handie, many of the local boys say goodbye to him in a friendly way. The book says that many of the local boys like Rainbow because he is kind, which made me wonder how many of those boys were the ones who didn’t want Rainbow in school with them. The story isn’t clear on that point, although I have heard of that concept of some white people liking black people as long as those black people “know their place.” I suspect that the situation in this town may be something like that. Maybe most of the townspeople accept Rainbow in a general way, as a neighbor and a worker and someone they might wave to or chat with, but they can get offended or even nasty if he starts getting above the station that they think he should occupy in life. We don’t have any specific names of people who have harassed Rainbow, so we don’t know if any of them are also sometimes friendly, as long as they think they have the social upper hand. It just strikes me that many of Rainbow’s relationships with the people in this village are probably conditional ones, the condition being that he doesn’t seem like he’s trying to be as good as or better than they are.

Handie and Rainbow haven’t been far from home at this point in their lives, and going to this new town will be a major adventure for them. Mr. James knows that Rainbow may have some problems from the people they meet along the way and that Handie may have trouble finding places for them to eat and sleep on their journey because Rainbow is black. However, Handie decides that he really wants Rainbow and that he’s willing to take responsibility for the both of them and deal with whatever problems they encounter. When Handie promises Rainbow that Rainbow will eat as well as he does, he’s promising that either he will make sure that people give Rainbow the services that they both need or that he will forgo those services himself. He will only stay and eat in places that accept Rainbow as well, whatever that means for them both along the way. Handie is becoming a young man, and as befits a real man, he’s taking responsibility for someone younger and is determined to look after him as both an employer and friend. There will be more to say about this as we continue through the story.