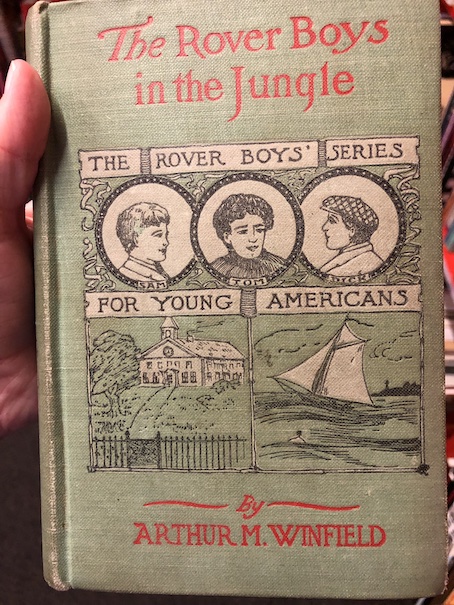

The Rover Boys

The Rover Boys in the Jungle by Arthur M. Winfield (aka Edward Stratemeyer), 1899.

My Foreword

I wasn’t particularly eager for this book after the first one in the series. I didn’t think the Rover Boys was as much fun as later Stratemeyer Syndicate books and there are some instances of racial language that are uncomfortable to explain. However, this is the book where the boys actually go to Africa in search of their missing father, and it resolves one of the major problems that the first book in the series set up, and I wanted to see it end.

As the book says at the beginning, the boys’ father went to Africa before the beginning of the series to look for gold mines and hasn’t been heard from since. The boys don’t know if their father is alive or dead, and meanwhile, the boys’ enemies from the first book in the series are still hanging around. The Baxters were put in prison for attempting to kidnap Dora at the direction of Josiah Crabtree in the book immediately before this one, but Dan Baxter escapes early in this book, and Crabtree is still around somewhere. The introduction and first chapter to the book brings readers up to date on developments from the previous books, sort of like the introductions to episodes of movie serials that didn’t exist at the time these books were written. Books in this series really need to be read in order, and if you skip any, like I did, you really need the introduction to bring you up-to-date.

The Story

There is a new boy at school, Hans Mueller, who is from Germany. This book was written before World War I, so there is nothing critical or derogatory about Germans, but the boys decide to tease Hans a little by playing up myths of the Wild West to scare him. They tell him that the school will be teaching them how to fight Indians (Native Americans) and that he’ll have to learn how to scalp people. Hans doesn’t know what they’re talking about at first, and when they explain it to him, he’s alarmed. (Good, Hans. That’s a sign of sanity.) Hans says that the only time he’s seen American Indians was at a traveling Wild West show that came to Germany, and he thought they looked scary. The other boys have a laugh about spooking poor Hans and drop the matter.

I mentioned in my last Rover Boys review that early Stratemeyer Syndicate books had archaic racial language and sometimes questionable racial attitudes that was later rewritten when various series were reissued. This early series hasn’t been revised. This first scene with Hans isn’t really so much a slur against Native Americans as prank with the boys playing up Wild West stories, but the book is just starting out.

Hans becomes the boys’ friend, but they prank Hans again later, scaring him with Tom wearing a Native American costume as he threatens to scalp him to continue their earlier joke, and they use the term “red man.” (We haven’t even gotten to Africa yet, so I was cringing at this point at what might be in store.) When Hans realizes that it was all just a prank, he tries to get the better of Tom by taking away the gun that Tom was using as a prop to scare him, and Tom tells him that the gun is too old to fire and isn’t dangerous. He just found it in the barn, and it’s all rusty. Tom tells Hans to pull the trigger and see that it won’t fire, which is the dumbest thing that anybody can do with a random old gun they just found somewhere. The gun explodes in Hans’s hands, knocking both Hans and Tom unconscious and scraping them with shrapnel. The other boys are scared, but they finally manage to bring them both around. Tom is horrified when he realizes what happened, saying that he’s been playing with that gun for awhile and pulled the trigger a dozen times himself, which is why he thought that the gun was unloaded and harmless (meaning he did the dumbest thing that anybody can do with a random old gun they just found somewhere repeatedly because, up to this point, dumb luck was on his side). He is shocked to realize that he’s lucky that he hasn’t shot somebody before and that he and Hans weren’t killed by the exploding gun. He apologizes to Hans and promises that this is the end of the pranks. Tom was always the lead prankster in earlier books, but he grows up a little here, realizing that reckless pranks have consequences.

At school, the boys participate in a kite flying contest, and Sam is almost pulled over the edge of a cliff by his kite. (Seriously.) Dora tells Dick that her mother had a dream that Crabtree tried to shoot him in a forest. (Prophetic?) The boys also have a run-in with Dan Baxter, who is still lurking around and swearing revenge.

Then, the boys turn their attention to a thief at school. Sam witnesses someone, who is probably the thief, sneaking around at night. Unfortunately, he didn’t see the person’s face, only describing this person as tall. Captain Putnam comes to believe that Alexander “Aleck” Pop, a black man who works for the school, is the thief because he receives an anonymous note that says he’s guilty. Sam doesn’t trust the anonymous note and tells the Captain so, saying that he can’t believe anyone as good-hearted as Aleck is would be a thief. However, the Captain insists that Aleck’s belongings be searched, and some of the objects that have been stolen turn up among his stuff. It’s a pretty obvious frame, and Alexander protests that he’s innocent, but Captain Putnam doesn’t believe him. There’s some ugly racial language used during this part. The word “coon” is used twice, and when the students at the school discuss the situation, one says the n-word. Fortunately, our Rover boy heroes aren’t the ones using that language, and Tom even tells the boy who used the n-word that he’s just resentful against Aleck for catching him doing something he shouldn’t have done earlier. The boy who used the n-word, Jim Caven, is portrayed as mean and unreasonable, and he gets into a fight with Tom in which he almost hurts him very badly. I was uncomfortable with the language in this scene, although I was somewhat reassured to see that it was used to characterize the ones using the worst of it as being the bad characters. My reassurance wasn’t complete because that’s not the only questionable racial language in the book.

Captain Putnam sends someone to escort Aleck to the authorities. He says that he supposes that the boys think he’s being too harsh with him, but he’s also suspicious of Aleck because he knows that members of his family have been in trouble with the law, too. The boys say it isn’t fair to blame him for things his relatives did and that they still don’t think he’s guilty. However, Aleck escapes before they reach the authorities, and they hear rumors that he went to New York City and boarded a ship to go overseas somewhere. The boys are sad, thinking that maybe they’ll never see him again. (You know they will.)

It’s not much of a surprise when the Rover boys later learn that Jim Caven has sold some things that match the description of other objects that have been stolen. Apparently, he’s been the thief all along and deliberately framed Aleck to get revenge on him. (I partly expected that the thief might be Dan Baxter, considering that he’s escaped from jail and is hanging around somewhere, probably needing money.) When the other boys confront Jim Caven, he flees into the woods. The other boys explain the situation to Captain Putnam, and he searches Jim Caven’s belongings, finding the rest of the stolen items. (You know, they could have just conducted a general search of the school and everyone’s belongings before this. This is a military academy, so a surprise dorm inspection wouldn’t be out of character, and it would have settled the matter much earlier.) Aleck’s name is cleared, but since he’s fled, they don’t know how to find him and tell him. Captain Putnam is sorry that he didn’t believe Aleck before.

However, they don’t have much time to consider it because the boys are soon summoned home by their uncle because he’s had news of their father. A ship captain has written Uncle Randolph a letter saying that his crew rescued a man who was floating on a raft off the Congo River. The man died soon after they brought him aboard their ship. They don’t know who the man was, but he was carrying a letter from the Rover boys’ father saying that he found a gold mine in Africa but was taken captive by King Susko of the Bumwo tribe (not a real African tribe, I can’t find anything about it) in order to prevent him from telling the secret of the mine to outsiders. Specifically, the tribe is afraid that the English and French colonizers will come to loot the mine and kill them. (Actually, a depressingly reasonable fear.) Anderson Rover explains in the letter that they don’t understand Americans. (That wouldn’t help, Anderson. Your boys attend a school run by a man who served with General Custer, and if this tribe knew what happened to Native Americans when gold was discovered on their land, they wouldn’t be reassured at all.) Anderson Rover is in fear of his life and asks his brother Randolph to come and rescue him if he can, but the letter is dated a year ago, so his family still doesn’t know if he’s alive now or not.

Uncle Randolph tells the boys that he wants to go to Africa to find his brother and asks Dick to come with him, as the oldest of his nephews. Dick, of course, agrees to go, but Tom and Sam refuse to be left behind. They decide that all of them will go.

On the ship to Africa, they meet an English adventurer named Mortimer Blaze, who is going to Africa for big game hunting. Tom asks him what will happen if the big game decides to hunt him instead, and he just says that it will be a “pitched battle.” (Doesn’t sound appealing to me.) When they talk about the people in Africa, they use the word “native” a lot and not in a flattering way. The general attitude seems to be that the “native” Africans are not very civilized (I was expecting they would say that because of the time period of this book), and Mortimer Blaze tells stories about tribes of people who are either very tall or very short. (I think he’s really referring to people from folktales, which I covered in the Encyclopedia of Legendary Creatures.) At one point, the characters say that the warm climate is the reason why Africa hasn’t made more progress toward civilization, that the warmth makes people want to be lazy. The adults in the story shock the boys by saying that not only is there no Christianity but that people there don’t really believe anything in particular, putting them even behind people Christians would consider heathens. They also make a shocking comment at one point about unwanted children being fed to crocodiles. They conclude that “civilization” can’t come soon enough to Africa, even if it has to be forced in with weapons. (Wow. I knew there was bound to be a lot of generic “native” and “savage” talk when I started this book because of the time period, but these matter-of-fact slights and accusations sound like they came straight out of Mrs. Mortimer’s books about Countries of the World Described, which heaps criticism and accusations of violence and immorality on pretty much all of the people of the world. Mrs. Mortimer’s books are much older than any Stratemeyer Syndicate books, and I wonder if Edward Stratemeyer read them in his youth. It wouldn’t surprise me because the attitudes match, and here he is, passing it all on to the next generation of kids in the form of an exciting adventure story.)

In a stroke of good luck, they end up rescuing Aleck, who was stranded at sea from the ship he boarded during his earlier escape. Aleck is glad to see the boys again, and they tell him that his name has been cleared and the real thief was caught. Aleck is glad to hear that, but he’s worried when he finds out that the ship that picked him up is headed for Africa. Aleck reflects that he always heard that his ancestors came from the Congo region of Africa, but he doesn’t really want to go there because he’s used to life in America and wouldn’t know what to do in Africa. (The Rover boys and Aleck go on for awhile about how great the United States is, and I know they were trying to sound patriotic, but the way they said it felt oddly like a sales pitch to me. I felt like saying, “You don’t need to sell me on the place. I already live here.”) The boys explain how they’re going there in search of their father. Aleck decides that he’d rather join their expedition than stay on the ship, and he offers his services as a valet. Uncle Randolph and the boys are glad to accept his help, and Uncle Randolph says it might be useful to have a black man with them who they know and trust in case they need someone to blend in with the native population and spy for them.

In a surprising twist, the boys also run into Dan Baxter on their arrival in Africa. When they ask him what he’s doing there, he says that he got drunk and was Shanghaied onto a ship, forced to work as a sailor. He was treated cruelly on the ship and ran away as soon as he had the chance. Now, he’s alone and has no money and no way home. The Rover boys feel sorry for him and give him money for him to buy his passage back to the United States. Dan Baxter asks to join their expedition, too, and they consider it as a sign that Dan is starting to reform because of his expedition. However, Dan is still a bully and an opportunist, and when he gets a counter-offer from someone else who is willing to hire him to make trouble for the Rovers, he accepts that instead, still holding a grudge against the Rovers because his father always told him that Anderson Rover stole a mine from him years ago that would have made them rich.

When I reviewed the first book in this series, I complained about the various unresolved story lines and miscellaneous villains still running around at the end of the story, still left to work on their individual plots against the Rover boys and their friends. In this book, every unresolved story line and villain from the first book collides with each other in Africa. Not only is Dan Baxter in Africa coincidentally at the same time as the Rovers, but Josiah Crabtree is also in Africa, for completely unrelated reasons from either the Rovers or Dan Baxter. He does attempt to kill Dick, but Dick survives. He is even rescued from a lion by one of his brothers.

So, is there true resolution with the main villains of the story, Dan Baxter and Josiah Crabtree? Not really. I looked up summaries of other books in the series, and even after they get some comeuppance, they continue to come back in sequels.

What is resolved by the end of the story is that the Rovers find their father alive. They rescue him from the village where he was being held captive, taking some of the women and children from the village with them as hostages to keep the village warriors from attacking them. They say privately that they wouldn’t have really hurt the women and children, but they tell the men that they’ll kill them if they don’t let the rescue party go. (This was another shocking part for me because I wouldn’t have thought of any of the usual Stratemeyer Syndicate heroes doing this. Somehow, I can’t picture the Hardy boys going this far, taking women and children hostage and threatening to kill them.) Once the rescue party is sure that they’re safe, they release their hostages and head for home. Anderson Rover says that he did find a gold mine, and someday, he’ll come back and loot it, er, mine it, but right now, all he wants to do is go home with his boys. It would be heartwarming if I didn’t know that he’s going to come back someday for gold on land that belongs to someone else who would never willingly sell it to him, and his boys are talking revenge on the king of the tribe that held their father captive.

This book is in the public domain and is easily available online in various formats through Project Gutenberg and Internet Archive (which has an audiobook).

My Reaction

I already gave much of my reaction to this book during the description of the plot because much of my reaction had to do with the racial language of the book. I knew there were going to be problematic portions before I even started, but frankly, there were too many of them for me to go into detail on all of them. What I described gives the broad strokes. I won’t say the book is deliberately trying to be insulting to black people. Aleck is portrayed as a good character who was wronged by a white boy by being framed for theft. However, there is a kind of casual racism in the story, like the casual references to how “uncivilized” Africa is and the characters’ off-hand supposition that it’s probably due to the climate there. I wouldn’t say that the characters or author hate black people (except maybe the non-Christian ones who feed children to crocodiles, which sounds like things Mrs. Mortimer accused various people of doing in the worst parts of Countries of the World Described), but I would say that there is a kind of condescension and dismissiveness that everyone, characters and author, seems to take for granted.

I can’t recall any of the characters using the phrase, “you know how they are”, but that’s the vibe I was getting. I got the feeling like the characters were saying things to each other and the author was saying things to his child readers with that sort of knowing tone, like “we all know these things.” No. “We” don’t. I know that Stratemeyer probably got a lot of this from a combination of old minstrel shows and Mrs. Mortimer or something very similar because I’ve seen Mrs. Mortimer‘s books, and I know how she talks. I also know why she says the things she does, and I’m not putting up with her attitude, even when it’s coming from someone else. Maybe the Rovers boys as characters and their child audiences would have read her books or similar ones before and nodded along with what Stratemeyer says because it confirms “information” they’ve seen before, but I’ve had more than my fill of wild accusations and crazy conspiracy theories, and I have no more patience left for any of it.

Mrs. Mortimer portrayed her book series as a factual introduction to world geography and the habits of people in different countries, but the truth behind her criticism, condescension, outspoken rudeness, and many of the wild accusations she makes about badly-brought-up children, dead bodies floating in rivers or just left in the street (depending on nationality), or the “antics” of “savages” around the world is her religious agenda (and, I think, probably some personal emotional and self-esteem issues, but that’s just a guess). She used missionaries with their own agendas as references for anecdotes in her books and tried to make people of various religions around the world sound evil and crazy on purpose to emphasize why “the Protestant” is the best religion (her words – she was specifically Evangelical and downright pushy about it). I would say that she also never hated black people … except maybe non-Christian ones, who as I recall, she claimed didn’t know what religion they were and were given to “antics”, dancing around and yelling or something. She wasn’t too clear on that point, probably because she didn’t know what she was talking about herself. On the other hand, she seemed inclined to be sympathetic to black people in the US who were victims of ill treatment, probably because they were Christian and most likely Protestant, which would have made all the difference in the world to her. She probably would have been okay with Aleck because he’s a Christian who was born in the US and has definitely never fed a baby to a crocodile in his life. She did not approve of the the concept of slavery at all and wouldn’t have tolerated physical cruelty of anyone due to race, which is to her credit, but none of that stopped her from spreading stories and rumors of violent savagery and teaching children that anyone who believed anything other than Protestant Christianity was “ignorant”, “savage”, and “wicked”, all words she actually used in describing people from various countries around the world because that’s what she wanted young children to “know” about other people. Mrs. Mortimer’s religious prejudices probably would have gone over the heads of the children who were these books’ original readers, especially if it echoed the talk of the children’s parents, but that’s how we end up with generations of children who grow into adults with casually racist ideas, thinking nothing of it, throwing around racist language without a clue or a care for the consequences. It’s in the book because it’s what “we” all “know”, dear Mrs. Mortimer said as much before, and Stratemeyer is just saying what “we” were all thinking, right? I think that’s about how that goes.

Let me bring you into the real world. If readers want to know what was really happening in Africa during the 19th century, there are far better sources. Africa is an entire continent, and there were many complex events happening all over, particularly related to European colonization. Outside forces were claiming territory in Africa, not so much for benefiting the people there and bringing them “civilization” as accomplishing their own personal aggrandizement and enrichment. (You know, rather like a man who is already rich in his own country coming to find and claim a gold mine that’s on someone else’s land because he’s addicted to the thrill of the hunt and acquisition and uses that thrill to hide from his own personal problems that he doesn’t want to face at home, like dealing with the loss of his wife and the raising of his boisterous sons. Just saying.) There were wars, famine, and disease in various parts of Africa during this period, partly due to internal power struggles among different African groups and leaders. I don’t know if anybody ever fed anyone to a crocodile on purpose, but infanticide is part of the dark side of humanity that comes out when times are desperate and hopes of survival in general are low. It’s a symptom of a society that’s suffering, and societies have suffered in that way many times around the world. If someone is likely to die soon after birth anyway, the hopeless parents might say, why even try? I suppose some might be tempted to say that having a religion that forbids killing children would help, but it hasn’t always, and having food also helps. I don’t blame 19th century missionaries for attempting to help people, but those who came in with a sense of self-importance, deciding ahead of time what would help without understanding the situation they were walking into, often didn’t help. Missionaries sometimes ended up getting killed in the middle of the unrest and power struggles. Some were even actively deceptive, using trickery and their position to gain advantages for themselves or the governments they represented at the expense of the people they were supposedly trying to help. But, the 19th century wasn’t all war, famine, and exploitation in Africa. The missionaries who were serious about doing some good and set up practical schools did provide useful centers of learning that helped educate future leaders and professional people and gave them tools they could use to build the lives they wanted. African societies did continue to build their own nations and identities. Overall, the colonization of Africa was more of an intrusive, disruptive force, providing additional hardships and obstacles to success more than solutions to any problems that Africa had before, not the glorious “civilizing” force that prevents people from feeding children to crocodiles that the book described.

So, now that I’ve talked about the historical and cultural influences behind the more uncomfortable parts of this book, I think it’s pretty obvious why early Stratemeyer Syndicate books had to be rewritten and revised in the mid-20th century. I knew this book was going to be cringe-worthy in places, but I have to admit that I was surprised at just how bad certain parts got. I hadn’t even considered that the word “coon” might appear. I never heard that word growing up and didn’t even know what it meant until I was in college, so I was pretty taken aback that a just-for-fun book for kids would use it, even one from the late 19th century. I suppose having grown up with the tamer, revised versions of books from the Stratemeyer Syndicate, I underestimated what the older series were like. I can only hope that I’ve made it pretty clear for people reading this review what the problems with this series were.

I debated about whether or not to even post this review, but I’ve talked about some uncomfortable books before (and said many highly critical things in my earlier rant about Mrs. Mortimer, my favorite example of a very popular bad influence in children’s literature – if you only know about her from The Peep of Day, you haven’t seen anything yet, even though the first chapter of that book is one of the most disturbing things I’ve ever read that was intended for small children). I’ve been planning a page discussing Stratemeyer Syndicate series books because they have been an important force in American children’s literature for so long, and it seemed only right to talk about their first series. So, now I’ve talked about it, and nobody else has to suffer through this book if they don’t want to. I found the characters, language, and situation aggravating, and the rewards for perseverance were inconsequential. This is certainly not something to spring on suspecting people, especially modern children, who might try using certain words for the attention-getting shock value without really understanding what they mean. I would say that this series should be primarily for adults interested in the history of children’s literature and others who know what they’re reading, understand what’s behind it, and can draw the line between fictional book and real life.

I’m not sure if I want to read any further books in this series because the unresolved problems of the stories get on my nerves, and there will probably be further issues with racial language, and I’d just have to repeat all the same explanations I’ve already given. I’m not saying a firm “no” to the rest of this series because there are indications that some people would like to see more coverage of them, but if I do any more, it’s probably going to be awhile and will only be delivered in small doses.

I wasn’t quite expecting to have these Mrs. Mortimer flashbacks from this book, but in honor of that experience, I might as well say that even though I’m leaving the Rover boys behind for now, I’m planning to go read many other useless novels “about people who have never lived”, which Mrs. Mortimer despised, and because I have access to some of them in audio book format, I can listen to them while knitting something completely unnecessary just because I want to. (If you read my rant/review about Countries of the World Described, you know what I’m talking about.) I’m not going to do it just because it would annoy Mrs. Mortimer. It’s something that I enjoy and do routinely anyway. I would do it even if it was something I thought Mrs. Mortimer would actually like. It’s more that knowing that she would have disapproved and can’t do anything about it makes me feel like we’re even because that’s the way I feel about her books and others like them.

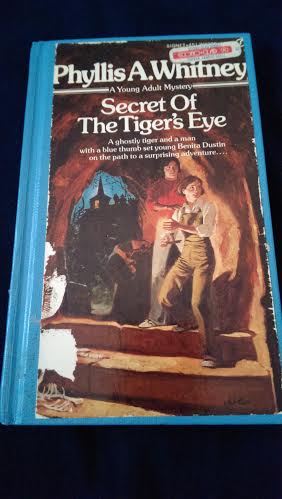

Secret of the Tiger’s Eye by Phyllis A. Whitney, 1961.

Secret of the Tiger’s Eye by Phyllis A. Whitney, 1961.