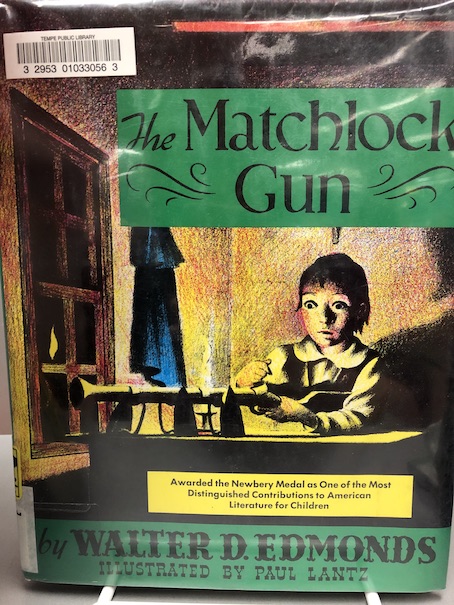

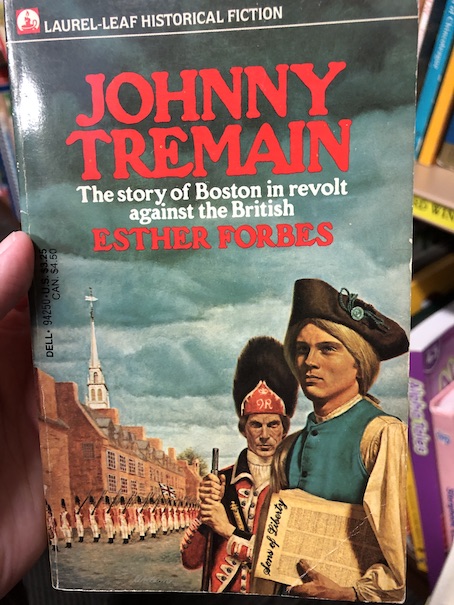

Johnny Tremain by Esther Forbes, 1943, 1971.

The story takes place in Boston around the time of the American Revolutionary War, and famous historical figures appear in the story.

Fourteen-year-old Johnny Tremain is a young apprentice to a silversmith. Even though he is one of the younger apprentices, he has talent and is favored by the silversmith. His favored position allows him to boss the other apprentices, and the silversmith is even considering having him marry one of his granddaughters when he has completed his apprenticeship so he can inherit the business. Johnny doesn’t mind the idea of marrying one of the granddaughters, although he is in the habit of teasing them, and inheriting the business would give him a steady future, although the business isn’t particular lucrative. Most people basically like Johnny, although one of the older apprentices, a boy called Dove, resents him.

Johnny has one particular flaw, and that is that he is arrogant and prideful. While he is talented, he gets overconfident and too full of himself because of his talent. The silversmith even warns him and lectures him about it, telling Johnny not to lord it over the other apprentices that they are not as gifted as he is.

However, Johnny doesn’t listen to him, and he soon pays the price for it. The reason why the silversmith’s shop hasn’t been very lucrative is because the silversmith is getting old, and he can’t work as hard as he used to. That’s one of the reasons why Johnny feels like he has to push the pace in the shop and keep the other apprentices in line. When the silversmith is late making a particular order, Johnny takes it on himself to complete the work on a Sunday, which is forbidden by the laws of Boston at that time and would have been forbidden by the pious silversmith, too, if he knew what Johnny was doing. While Johnny is working, Dove hands him a crucible with a crack it in, thinking to embarrass Johnny by ensuring that the work will go wrong. Unfortunately, it turns out to be worse than that. Johnny’s hand is badly burned by molten silver.

With a crippled and useless hand, Johnny doesn’t see how he can continue his apprenticeship and become a silversmith. For the first time in prideful Johnny’s life, he is an object of pity, and he seems to have no future ahead of him. There aren’t many kinds of work a person in his time can do with only one usable hand. The silversmith’s youngest granddaughter has always been sickly, and people think that she isn’t likely to live to adulthood. Even the girl’s own mother says that it hardly seems worth the effort of raising her when she isn’t likely to survive, and privately, Johnny has also agreed. Now that Johnny is disabled, seemingly useless, and without a future, is he also hardly worth anyone’s help?

The silversmith’s daughter-in-law, Mrs. Lapham, seems to think he isn’t worth anything. In spite of her being the one who originally insisted that he do the task on Sunday that crippled him, she begins giving him repeated and casual insults like “lazy good-for-nothing” and “worthless limb of Satan.” Her previous praise and encouragement for Johnny and wish for Johnny to marry one of her daughters hadn’t been based on any liking for Johnny but only based on what she thought Johnny could do for her and her daughters in the future. Now that he can’t take over the business, Mrs. Lapham is ready to kick him to the curb. Mrs. Lapham discourages Johnny from eating much food, tells him that she’ll be needing the place where he sleeps soon for someone else to help her father-in-law with his shop, and tells the silversmith that he should get rid of Johnny. The silversmith refuses to kick the boy out onto the street with nothing and no prospects, especially since Johnny has been doing small chores for the family to earn his keep. The silversmith tells Johnny that he cannot continuing learning the silversmithing trade, so he’s going to have to find a new one. He encourages Johnny to explore the city and watch different people at their trades until he can find one that he thinks he can do, and then, he will give the contract for Johnny’s apprenticeship to his new master.

However, Johnny is still prideful and can’t see himself doing any of the unskilled trades that might take him, and he only half-heartedly tries to find a new position. He still sees himself as a craftsman, and that’s all he really wants to be. He still feels like other jobs are beneath him. One day, he goes inside the printing shop for the Boston Observer, which the silversmith disapproved of for trying to stir up dissent and resentment against the English king among the colonists, and immediately is fascinated at the way the boy working in the shop interviews a woman about an advertisement for her lost pig. Johnny feels an odd friendly feeling toward the boy, who is a good and patient listener. When the woman leaves, Johnny finds himself pouring out his own story to the boy, whose name is Rab, without his usual arrogance. Rab understands Johnny’s feelings and agrees that most of the jobs that would be open to him now are the unskilled jobs he doesn’t want to do. He says that the Observer could hire him, but it would be a position as a delivery boy and messenger, but that doesn’t sound like the kind of work Johnny really wants. Still, Rab tells him that if he can’t find anything else, he could come back and take the messenger job. Johnny hopes that he can come back and tell him that he’s found a much better job.

However, Johnny still can’t find someone to take him. When he tries to get a job from John Hancock, whose project was the one that ruined Johnny’s hand, John Hancock is repulsed at the sight of Johnny’s hand and won’t even take him as a cabin boy for one of his ships. Johnny is angry and despairing when John Hancock sends him away, but John Hancock sends a slave after him with a whole back of silver, apparently out of guilt. Hungry because he’s had so little to eat lately, he goes to a tavern and orders a great deal of food. He is disappointed to see how much of his money he wasted and realizes that he has been a fool for ordering too much all at once. He spends the rest of his money buying presents for the silversmith’s daughters and new shoes for himself. When Johnny comes home in his new shoes, Mrs. Lapham accuses him of stealing them from someone because she can’t imagine that he could earn enough money to buy them. The girls are happy with the presents until the youngest one suddenly gets upset at Johnny touching her with his bad hand because it looks weird and she’s afraid of it, ruining the moment.

There is one last thing Johnny has that might help him. He has had a silver cup his entire life with his full name on it: Jonathan Lyte Tremain. The cup also bears the family crest of the Lyte family, a wealthy merchant family in Boston. Johnny’s mother never introduced Johnny to her relatives before she died, although she said that she was from a genteel and educated background and their own names, Jonathan and Lavinia, were family names. Johnny knows that the head of the wealthy Lyte family is also named Jonathan Lyte, so he thinks that he could be a relative. For some reason, his mother didn’t want him to show the cup to anyone, although she told him to keep it in case he ever needed it. She said to only show it others if he was in dire trouble and it seemed like even God Himself had forsaken him, and his current situation certainly qualifies.

When Johnny goes to see Mr. Lyte, Mr. Lyte doesn’t believe that he’s really a relative. He thinks that it’s just a story to get some of the Lyte family’s money, and he’s heard stories like this before. Johnny argues unpleasantly with Mr. Lyte before telling him that he has a silver cup that will prove the relationship. Mr. Lyte seems interested in the cup and tells Johnny to bring it to him that night. Before returning to Mr. Lyte with the cup, Johnny goes to Rab and tells him what he’s about to do. Rab gives him some food and a change of clothes before he goes but warns him that Mr. Lyte has been deceptive and unethical in his business dealings.

Rab’s warning is prophetic. When Johnny produces the silver cup, Mr. Lyte agrees that it is part of a set that the family has, but he says that the cup was stolen from his house only two months before. He accuses Johnny of being the thief and has him arrested. Rab finds out about it and asks Johnny if he showed the cup to anyone else before the date when it was supposedly stolen. With his mother dead, the only other person who could vouch that Johnny had the cup before is Priscilla, the Lapham daughter that Johnny was originally supposed to marry before the accident that ruined his hand. Priscilla, called Cilla for short, is willing to testify in court that Johnny showed her the cup before, but Mr. Lyte begins exerting his influence on the Laphams. He places a large order for silver and pays in advance as a kind of bribe, and Mrs. Lapham, who has already decided that Johnny is no good, declares that she will keep Cilla locked up on the day of the trial so she can’t speak on his behalf, even though she knows young Johnny will be executed without her testimony.

Rab correctly realizes that some of the attitudes of people against Johnny are because Johnny is an arrogant hothead who has made enemies because of the sharp and snooty remarks he’s made to them and about them in the past. He points out that these people, who have felt oppressed by Johnny are now taking their opportunity to get even with him and get rid of him, just like the rival apprentice whose dangerous trick ruined Johnny’s hand. If Johnny is going to get out of this mess and change his life, he’s going to have to change his own attitude and behavior and learn to make friends, develop some humility, and show gratitude for the help that he receives.

Fortunately, Rab knows a lawyer who is willing to take Johnny’s case without pay, Josiah Quincy (historical figure – Johnny notices that he has a dangerous-sounding cough, like the kind his mother had before she died, and the real-life Josiah Quincy did die of tuberculosis), because Mr. Lyte is a Tory who has crossed the Colonial Patriots who call themselves the Sons of Liberty with his crooked business dealings. Johnny’s trial becomes the latest skirmish between the two sides of the Revolution that is building. For the first time in his life, Johnny does have cause to be truly grateful to others. Unfortunately, he has also made one more enemy. Mr. Lyte is publicly embarrassed at having been shown to bring a false charge against an unfortunate boy in court, and if anyone is even more proud and arrogant than Johnny has been, it’s Mr. Lyte.

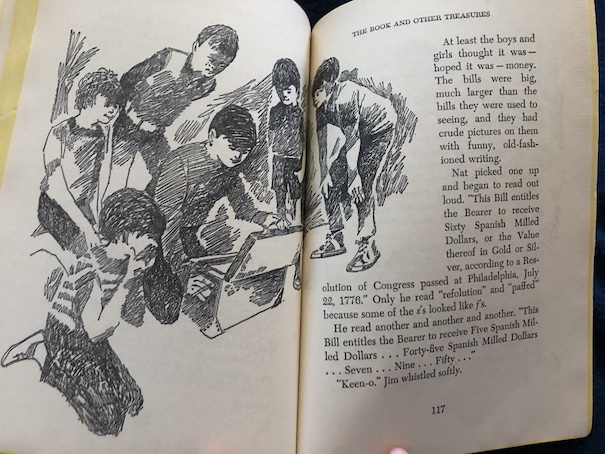

Johnny takes the job of delivery boy for Rab’s newspaper and becomes more involved in the politics of the Colonies and the growing Revolution. He learns how to ride a horse for the first time, even learning to manage a previously abused and skittish horse. Johnny becomes known as a good messenger and finds other side jobs. He develops his use of his uninjured left hand and even increases his use of his damaged right hand. He becomes better read and educated as he builds his messenger career. However, Johnny is also drawn into the growing conflict and learning the truth about his relationship with Mr. Lyte.

The book is a Newbery Medal Winner and available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive (multiple copies). It was made into a movie by Disney in 1957.

My Reaction

The Background of the Book

Because this book is an award-winner and has patriotic themes, it is a popular book for children to read and study in American schools. I didn’t actually read the book when I was in elementary school, probably because it contains works like “slut”, but I remember our teacher showing us the Disney live-action movie version from 1957. I still sometimes think of the Liberty Tree and the Sons of Liberty song from that movie. If you read the comments below the YouTube clip of that song, some people were commenting about seeing this movie when they were in 5th grade at school, and that’s about when I saw it, too, back in the 1990s. I found the song stirring then, although it looks a little corny to me now. For patriotic musicals, I prefer 1776, which I saw in high school and which is also corny but brings up some interesting historical topics. 1776 was based on a Broadway play written as the US approached its Bicentennial. If you look at my page of books from the 1970s, you’ll see that people were writing books for children focusing on the American Revolution, Colonial America, and other patriotic themes because the Bicentennial was on people’s minds at the time. The 200-year anniversary of the country was something people wanted to celebrate, and they used it as an opportunity to educate children about the history and lore of the country. Part of what makes Johnny Tremain interesting is that the original book was written in the middle of WWII, which was more of a worrying time rather than a celebration. The Disney move was made after the war, when people were in a celebratory and triumphant mood about how well the country was doing, and it ends on a triumphant note, but the original book was much darker.

During WWII, children’s authors had a choice about whether or not to mention the war in the books they were writing. If you look at my page of books written during the 1940s, you’ll see that some children’s authors addressed the war directly and even worked it into the plots of their books while it was still happening. I’ve marked which ones did that on the 1940s page. However, for those who didn’t want to write contemporary stories mentioning WWII, there were other options. Some authors wrote just-for-fun stories that had nothing to do with the war at all, which were good for helping children relax and take a break from the harsh realities going on around them, and some wrote books with historical themes.

The books with historical themes, like Johnny Tremain, often had a patriotic focus, putting the current war into perspective by reminding children that the country had been through struggles and dark times before, and reinforcing the patriotic ideals that made the struggle worth it. You can see these themes in both American and British books written around the same time, trying to help children understand that concepts of the war, what people were fighting to protect, and why the sacrifices and deprivations of the war were necessary.

There is a scene in Johnny Tremain where James Otis tries to make sure that the Sons of Liberty who are ready to fight the British understand what they’re really fighting for, the larger implications for the rest of the world, and the sacrifices they might make, including their lives. Some of his speech seems a little anachronistic with its mention of rights for everyone, regardless of race, because slavery is practiced during this era. I suppose it’s not impossible that Otis said something like that at some point, but racial equality would not have been high among the priorities of these people in real life. It felt like it was meant more for modern, 20th century audiences. He also makes a reference to rich people in France running down poor children in their carriages, which sounds like a reference to a scene in Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities, from 1859. My impression is that Otis’s speech in the book is meant more for the book’s original audience of children during WWII than for the original Sons of Liberty. Dr. Warren later makes comments about young men who give up their lives so that others can stand up like men and how a hundred or two hundred years later, men will be doing the same thing. I think those comments are also meant to help 1940s children understand why the men of their time, possibly their own fathers and brothers, might be willing to sacrifice themselves as soldiers.

Johnny Tremain is really a rather dark story in places, which is probably why my teachers showed us the Disney movie rather than having us read the book. They did have us read plenty of other dark stories when I was in school, even ones much darker that this one, although most didn’t have the kind of objectionable language this book does.

Story Themes

Although this is an historical novel, the main focus of the story is the transformation in young Johnny’s life and character as he suffers from misfortune, redeems himself, and plays a part in larger events and history. At the beginning of the story, even though Johnny is an orphan, he seems to have his future made at a young age. He has a particular talent for working with silver, and he’s in an apprenticeship and poised to take over the master’s business someday. However, like many classic heroes, he has the fatal flaw of hubris – he’s too proud of himself. It makes him arrogant and overconfident. His arrogance makes enemies of his fellow apprentices, and in one moment when he pushes his luck, his chief rival does something that seriously harms Johnny and apparently ruins his future. Johnny, who has never had any real patience or sympathy for other people who are less gifted or fortunate than himself finds himself in the position of needing patience and sympathy from others. His master sees the difficulty Johnny is in and tries to help him learn the lessons of humility that he needs to cope with the situation, but for someone as proud as Johnny has been, it’s not easy to cope with his humbled position. It’s a serious struggle for Johnny to find a new place in the world and a new path for his future. There are people who openly despise him for his weakened condition, which is unfair, and initially, he passes up some opportunities for improvement because he considers the jobs beneath him.

Johnny life changes when he finds himself in a situation so hopeless that he is really dependent on the help of other people. Some of those other people help Johnny in the court trial, not just out of a desire to help Johnny but also to embarrass Mr. Lyte by publicly exposing him for bringing a false charge. Still, they save Johnny’s life, and Johnny gains a new life by working for Rab’s family as a delivery boy and following Rab’s example in behavior. Rab is calmer and more thoughtful than Johnny, and he encourages Johnny to learn to be more thoughtful and to think before he speaks and acts. As Johnny does so, he notices that people begin treating him better because he begins giving the chance to do so instead of thoughtlessly offending them or picking fights. With Johnny’s change of attitude and behavior, he is able to forge new relationships, and new opportunities open up for him. While Johnny’s hand getting damaged seemed to be the end of everything to him and the delivery job at first seemed to be beneath him, these changes in his life actually lead to personal growth for him.

Through his work for the newspaper and the Sons of Liberty, Johnny becomes part of the American Revolution. It brings him into contact with many notable Revoluntionary war figures, including John Hancock, Josiah Quincy, Paul Revere, Samuel Adams, John Adams, and Dr. Joseph Warren. Not all of these figures are pleasant figures in the story. John Hancock, in particular, doesn’t treat Johnny well when he’s at the lowest point of his life. Dr. Warren is kind and attempts to help Johnny with his hand when they first meet, but at first, Johnny doesn’t want him to even look at it because he’s still ashamed of it and how it was damaged. Johnny later regrets that, and explains the details of his injury to him. The book ends with Dr. Warren performing a procedure to remove the scar tissue that has kept Johnny’s hand deformed. Without it, his hand will move more freely, and he will be able to fire a gun in the coming war and do other things he thought he would never be able to do again. It is uncertain whether or not he will ever regain enough dexterity to be able to return to being a silversmith, but his eyes have been opened to many other possibilities in life, and he has a cause to fight for first.

During the course of the book, Johnny also takes part in the Boston Tea Party and Paul Revere’s famous ride. His role as one of the participants in larger events is partly to teach and reinforce history lessons and patriotic feelings for the young readers of this book but also to show that even a flawed and somewhat disabled person like Johnny is worth something, has a future, and can participate in larger events and make their mark on the world. The more Johnny does participate in larger events and make connections with other people, the more his life also changes for the better and the more opportunities open up for him.

Life is Full of Mixed Feelings

I also noticed that there are many cases where people have mixed feelings about each other. As I said before, although Johnny becomes allied with the Sons of Liberty and believes in their cause, not all of them really treat him well, at least at first. Johnny also realizes that he doesn’t agree with all of their personal attitudes. At one point, he realizes that Sam Adams wouldn’t approve of the quality of mercy toward his enemies, but Johnny actually does. Although Johnny doesn’t like the British soldiers, there are moments when some of them do something kind or honorable. He doesn’t like them as a group, but he privately acknowledges that he can like certain ones as individuals in certain circumstances. Johnny comes to see the British soldiers as human beings who can be likeable, and as he sees that the situation around them is going to lead to war, he realizes that having to fight and maybe even kill some of these people would be painful. Although he still believes in his cause and is willing to fight for it, the seriousness and pain of war becomes clear to him.

Johnny’s ability to see multiple sides to people’s personalities and the capacity he has to show mercy even toward people he doesn’t like or who have actively tried to harm him are important developments of his character. Mrs. Lapham, Dove, and Mr. Lyte were all pretty bad to Johnny, in different ways. As the story progresses and Johnny’s condition in life improves and he has some separation and independence from both of them, he feels less resentful toward them both and even begins to see them in a better light. Personally, I don’t think that erases the unlikable and even dangerous sides of these characters. Mrs. Lapham would have happily watched Johnny be hung for a crime he never committed and was perfectly willing to take a bribe to lock up her own daughter, knowing that she was an important witness who could save him. That side of her personality is a definite side of her personality, and that is something that she definitely and knowingly did. However, Johnny later has a feeling of nostalgia when he remembers that Mrs. Lapham did have a hard life in some ways and yet was a hard worker, who always tried to look after her household, even when it was difficult, so she isn’t wholly evil. In some ways, her evil side and opportunism is a reflection of the hard life she’s lived and what she thinks she has to do to get ahead in the world and provide security for her fatherless daughters. Again, I don’t see her as being a really good person as a person because of what she does, what she thinks is acceptable to do, and how she treats other people, and I don’t believe that much of that was as necessary or excusable as she seemed to think it was. However, with some time and separation, Johnny starts to remember that she did have some relatively good sides.

I do note that, while it’s good that Johnny sees people for what they are, even acknowledging that unlikable people have their good sides, this does not mean that it would be good or healthy for Johnny to allow himself to be at the mercy or under the control of these people eve again. No matter how hard a worker Mrs. Lapham is, I can’t help but notice she is fundamentally untrustworthy. Knowingly helping to frame a helpless boy for a crime with a death penalty is pretty close to deliberate murder, and that’s about as bad as a person can get. The argument could be made that Mrs. Lapham didn’t know that Johnny didn’t steal the silver cup, but I don’t think that’s true. I’m sure that she was fully aware that he didn’t because of her declaration that she would lock up Cilla on the day of the trial, which indicates that Cilla told her what she knew and that the cup was honestly Johnny’s from the beginning, and she was determined to prevent Cilla from telling the truth in court, making sure that Johnny would die so she and her family could profit from Mr. Lyte’s bribe. No, from what I’ve seen of Mrs. Lapham, merely being a “hard worker”, while a good trait by itself, isn’t enough to redeem her as a character or make her trustworthy because she definitely doesn’t have that hard-working trait in isolation from her willingness to throw people under the proverbial bus and even try to get them killed for the sake of money.

Although Dove is never as sorry for the accident that hurt Johnny’s hand as he told their master he was. Behind the master’s back, he is gleefully cruel to Johnny when he has the opportunity. Admittedly, what Rab says about that being Dove’s form of retaliation for Johnny’s own arrogant meanness toward him is true, but it is equally true that Dove’s own behavior never improves even when Johnny’s does. Initially, Johnny swears revenge against Dove, but when he sees that his life isn’t really ruined by him and Dove gets some comeuppance in other ways, Johnny begins to feel a little more kindly toward him and no longer feels the need for revenge. (Although, he does get Rab to help him toss Dove into the harbor during the Boston Tea Party because Dove was trying to steal some of the tea for himself, in spite of the participants agreeing not to do that ahead of time, and attempting to lie about it. It’s not the grand revenge that Johnny initially envisioned, but it is a brief moment of comeuppance.) Johnny even treats Dove nicely after he goes to work as a stable hand for the British troops. Dove is loyal to the British, but the British are not nice to him in return, largely because Dove isn’t particularly competent at what he does and because he is obviously self-interested. Johnny realizes that he is lonely and could use friends, but even when Dove admits that Johnny and Rab treat him better than anyone else does (largely so they can pump him for information about the British troop movements), Dove still repeatedly tries to tell the British that Johnny is a spy for the Sons of Liberty and openly admits it to Johnny. Dove feels like it’s his duty as a loyal Tory to turn Johnny in, not showing loyalty to the people who have shown him the most kindness. Johnny understands all of that. While Johnny’s behavior has changed and improved, and because of that, Johnny is more respected by the even the British than Dove is. In the end, Dove is his own worst enemy, and his own behavior is the reason why more people don’t like him.

Mr. Lyte deliberately tried to have Johnny executed for a crime he didn’t commit. That was pretty horrible, and Mr. Lyte also steals the silver cup from Johnny when he attempts to sell it to him. It’s all the more horrible when Johnny is a young relative of his. However, there is something of an explanation behind it. Mr. Lyte didn’t recognize Johnny as a relative because he knew Johnny’s father under another name and had believed that Johnny’s mother, who was his niece, had died childless. Mr. Lyte is still an unethical man, both in his personal and business dealings, but although he was wrong about Johnny not being related to him, the one thing he was honest about was saying that was what he believed. His beliefs were wrong and the actions that were based on those beliefs were also wrong, but he wasn’t actually lying about those particular beliefs, even though he has lied about other things. Later, when Johnny’s life changes, he no longer cares about having the silver cup or any relation to the Lytes.

On the other hand, there are also some characters who seem likeable initially but who prove to have dark sides. The most notable character of this type is Lavinia Lyte, the daughter of the wealthy merchant, Mr. Lyte. At first, Johnny has a crush on her because she is pretty, although he knows that they are probably related in some way. However, he eventually discovers that Lavinia Lyte is silly, shallow, spoiled, snobbish, and uncaring. She takes Cilla and her little sister Isannah into her household as servants and companions when their family doesn’t have much money. It does help Cilla and Isannah monetarily, but Johnny notices that Lavinia treats them very differently. She initially only wanted Isannah because Isannah is a pretty and adorable little girl. Lavinia is supposedly mentoring Isannah as a protege and raising her to enter high society, but really, she treats her like a pet lap dog or a living doll she can dress up and play with. Isannah is young and impressionable and has never been much of an independent thinker, often imitating other people throughout the story. Under Lavinia’s influence, Johnny sees that Isannah is becoming spoiled and badly behaved, just like Lavinia, and is not developing properly, either intellectually, morally, or emotionally. Meanwhile, Lavinia treats Cilla like an ungrateful servant, calling her “stupid” when she doesn’t do things right, even when she is merely doing precisely what Lavinia told her to do in the first place. Johnny gets fed up with this situation and tells Lavinia off for it. In return, she snobbishly tells him that he’s just a ragamuffin boy. Although Johnny still feels some attraction for Lavinia because of her looks, he learns what her personal character is really like and what being around her really involves. This remaining attraction he feels for her dies when he understands their real family relationship.

Rab is generally a good character and a positive influence on Johnny, but even he has his faults. People in his family don’t communicate their feelings as much as they should, and Johnny becomes jealous and angry with Rab when he discovers that he’s been courting Cilla behind his back and not talking to him about it. Rab’s desire for a gun so he can fight in their cause also gets him into trouble a couple of times. Even as one of the nicest characters in the book, Rab isn’t perfect, either.

The characters in the story feel very real because they do have multiple sides to their personalities and often cause mixed emotions. Johnny also comes to realize that feelings about people and relationships can change over time. Some relationships develop for the best and others for the worse. It is a sign of Johnny’s growth as a character that he can see and acknowledge the complexity of the characters of other people and his own feelings regarding them. His ability to understand and manage his feelings grows throughout the story.