Da Vinci by Mike Venezia, 1989.

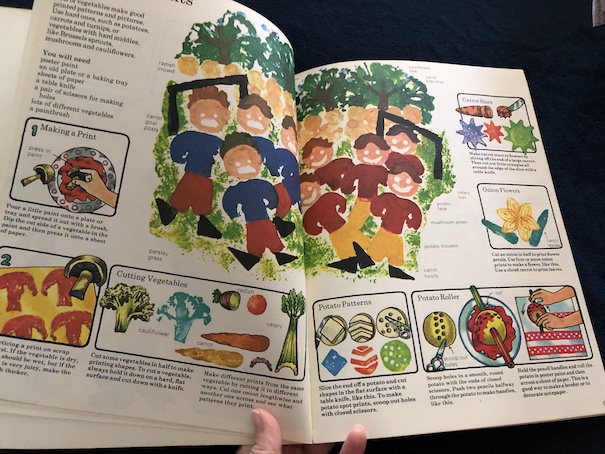

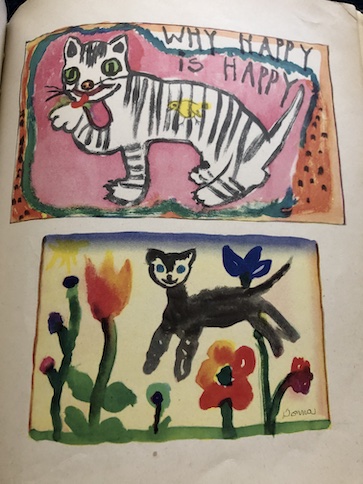

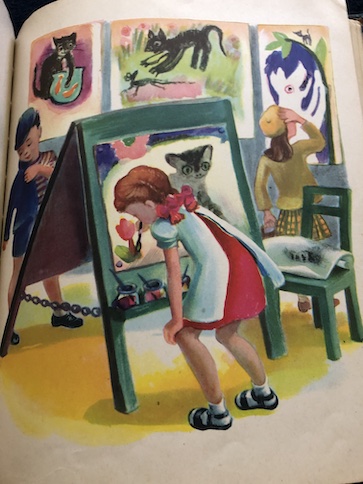

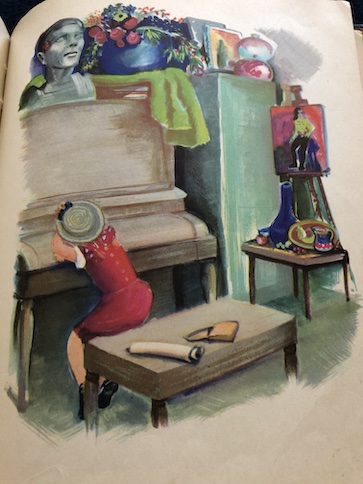

This book is part of a series of biographies of famous people from history. I’ve been familiar with the part of this series about famous artists since around the time the first ones were published. I was in elementary school school at the time, and we had the books because my mother used to teach the Art Masterpiece program at the school. She would come to class and talk about famous artists and show their paintings, and there would be an art project for the kids to do based on the style or subject matter of the artists. So, when I was young, we had books from this series (among other art books) around the house that she used for the art classes and a lot of arts and crafts materials (a tradition which exists to this day). At the moment, this is the only book from the series that I have because the book about Leonardo da Vinci was my favorite.

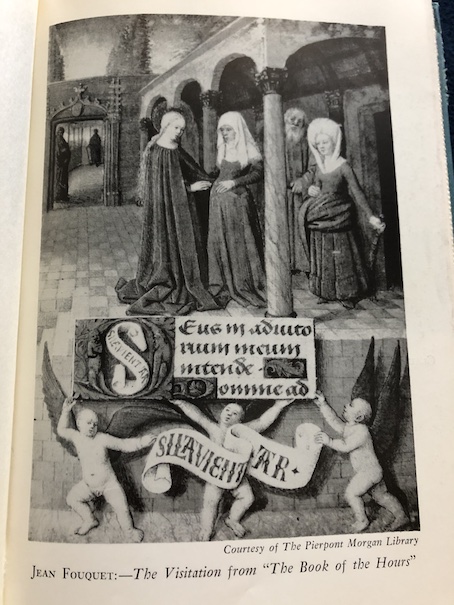

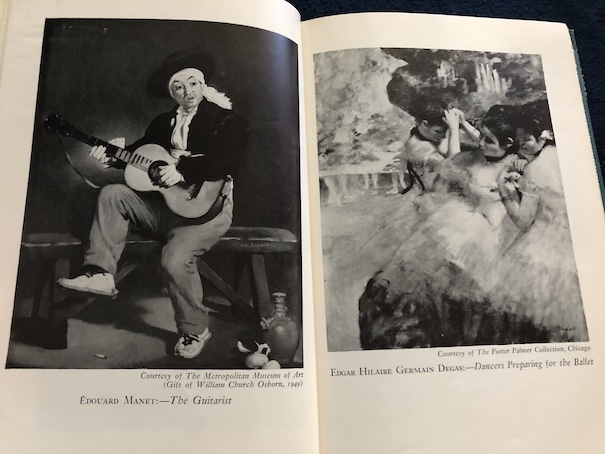

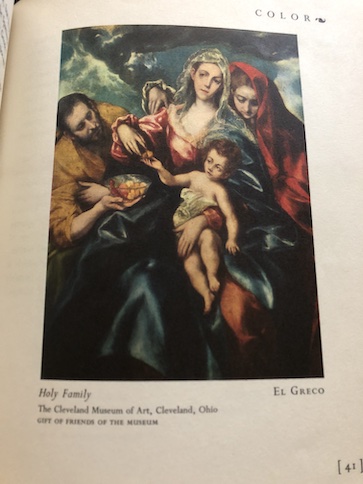

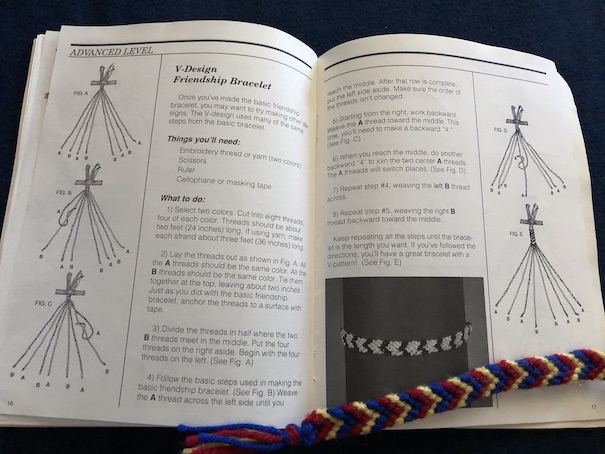

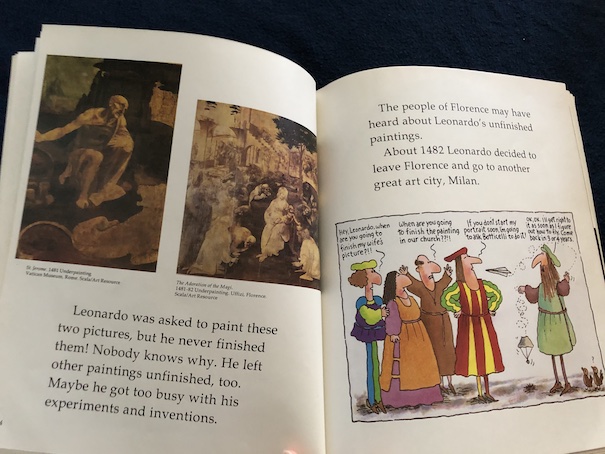

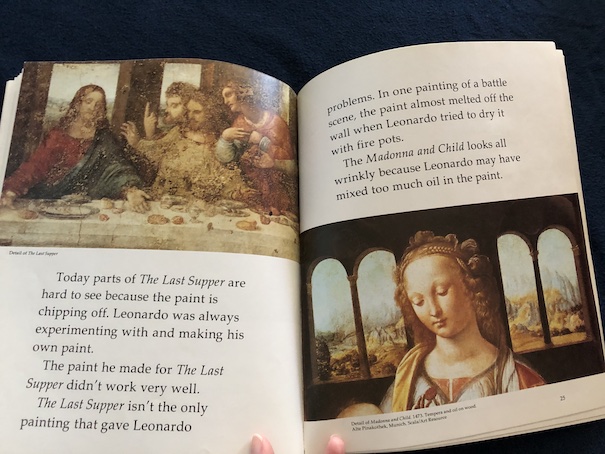

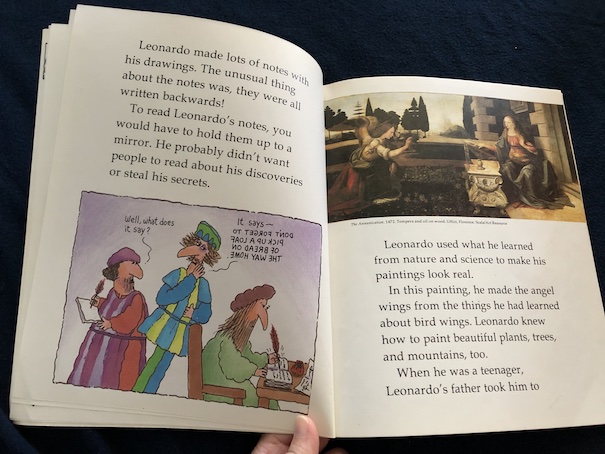

Leonardo da Vinci was one of the most famous artists of the Italian Renaissance, particularly known for his paintings The Last Supper and the Mona Lisa, but he was more than just a painter. The book is full of interesting facts about his life as well as his work. Aside from showing photographs of da Vinci’s work, the book also has humorous cartoons about da Vinci’s life, which is one of the things that makes this series of books fun.

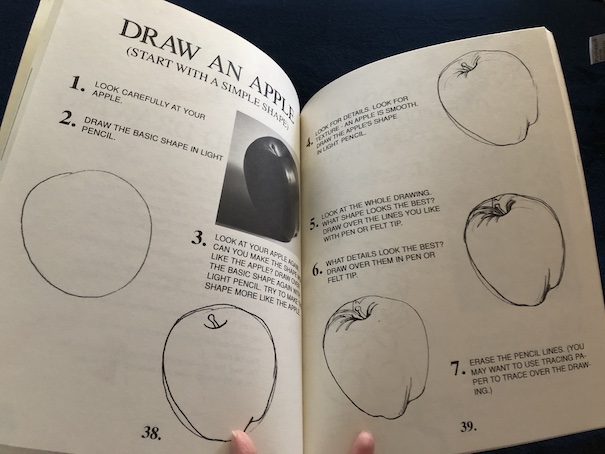

Leonardo began showing an interest and talent for drawing while he was still a child. Throughout his life, he also developed and practiced many other skills, including architecture and mathematics, music, and sculpture. He was a scientist and inventor, experimenting in many different areas, from the mixing of different types of paints to weapons design. Along the way, he found creative ways to combine his various interests. He used his drawing skills to develop his scientific ideas, and he used his knowledge of science to make his art appear more realistic.

You might wonder how one person could find so much time to do so much, but part of the answer is that he didn’t finish everything he did. He is known to have left some of his work unfinished, possibly because he got distracted by other, more interesting projects and pursuits or because he just couldn’t finish them to his satisfaction. Not all of his designs for inventions really came to anything, and not all of his experiments worked out, either. Some of his paintings are now deteriorating because the experimental paints that he mixed didn’t quite work out.

However, Leonardo da Vinci was a perfectionist, and the paintings that he did complete show excellent techniques and a high degree of realism that have been an inspiration to later artists for centuries.

One final thing I’d like to add is that this book is part of the reason I thought The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown was a dumb book. As I said, I grew up with art lessons. I read and loved this book about Leonardo da Vinci when I was a kid, and it has some very basic information about the life and work of Leonardo da Vinci that anybody who was seriously interested in him really should know. One of the cringiest parts of The Da Vinci Code for me was the part where our heroes are stupidly trying to figure out a message that is simply written backward. As this picture book about Leonard da Vinci points out, it’s common knowledge these days that da Vinci wrote notes using mirror writing. Some people, like the book suggests, think that he did that to make his notes harder for other people to read, although there’s also a theory that he did it because he was left-handed and that he decided that it was easier for a left-handed person to write that way. Left-handed people often complain about getting ink on their hands when they write left-to-right, but they don’t have that problem if they write right-to-left, so this might have been his attempt to get around the problem of ink-stained hands. Either way, if the people in The Da Vinci Code were such experts, they should have know this about da Vinci, and it should have been one of the first things they should have checked for. That’s not the only problem in The Da Vinci Code, but it’s one of the ones that rankled me the most because of how long I’ve known about this. (Also, The Da Vinci Code totally ripped off the albino assassin from Foul Play with Chevy Chase and Goldie Hawn, but that’s another issue.)

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive.