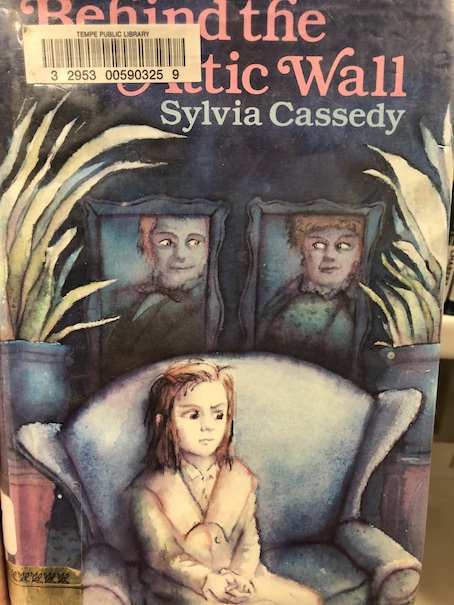

Behind the Attic Wall by Sylvia Cassedy, 1983.

This story is told as a flashback, so we know that things get better for the main character, but she is still haunted by her past experiences.

Twelve-year-old Maggie is an orphan who has been bounced around between foster homes and boarding schools because of her bad behavior. Her bad behavior is because she feels neglected and unloved. She eventually comes to live with her great aunts and an uncle in an old house that used to be a boarding school. Maggie has memories of the house where she once lived with her parents before they died, but no place she’s been since has seemed home-like.

When she first arrives, her eccentric Uncle Morris picks her up at the station. Uncle Morris has a sense of humor, which is both charming and also gets on Maggie’s nerves. When she gets a look at the institutional-looking old house where her great aunts and uncle live, she is physically ill. She has lived in various boarding schools and is horrified at the idea of living in another. Her last boarding school expelled her, and the headmistress called her a “disgrace.” Maggie had hoped that, for once, living with relatives might mean living in a real home.

Her two aunts, Harriet and Lillian, remind her of the headmistresses at boarding schools, although their rules are different from most headmistresses. They lecture her about health and nutrition and worry about her being undernourished. They give her old-fashioned, hand-me-down clothes to wear that Maggie assumes are the uniforms of this old school. One of her aunts gives her a baby doll, but Maggie tells her that she doesn’t like dolls and doesn’t play with them. She doesn’t have any dolls, and if she ever had any before in her life, she doesn’t remember. Her aunt thinks her rejection of this gift is horrible. Her aunts don’t seem to understand much about children, and they are both horrified when Maggie dumps out her glass of milk because they gave her warm milk instead of cold. However, her Uncle Morris is amused and tells her that she might be the “right one” after all. Maggie isn’t sure what he means by that.

After her aunt leaves her alone in her new room, Maggie plays with the doll a little, imagining that she’s explaining it to a group of girls who have never seen a doll. A game that Maggie often plays with herself is to mentally explain common things to a group of imaginary girls who don’t know what any of them are. Then, she goes exploring the rest of the old house. Because this building is so obviously an old school, she keeps expecting that she will eventually encounter other students, but there are no students. Maggie is the only child in the old house.

Maggie finds her aunts’ rooms and tries on their curlers, a necklace, and a fancy pair of shoes. She gets in trouble with her aunts for doing that, and that’s the moment when Maggie understands that there really are no other children around to see her get in trouble. At first, her aunts think that maybe agreeing to accept Maggie was a mistake and that they can’t handle her. However, they decide to keep her, at least for the present.

They explain to Maggie that the building where they live did use to be a boarding school for girls. It was founded by some ancestors of their, whose portraits hang in the parlor. Maggie is amazed at the idea of ancestors because she barely even remembers having parents and has little concept of her extended family. The old school closed after some kind of disaster, and it reopened in a new location down the road. Now, the new school is a private day school for both boys and girls, catering mostly to wealthy families, who can afford the fees. Maggie is horrified when she finds out that she will be attending this school because she knows that a poor orphan like her in her shabby, hand-me-down clothes is going to be an oddity among the wealthy private school students.

On her first day at the school, Maggie has a panic attack while imagining going through the routine of her teacher telling the whole class about her unfortunate history and the tragic deaths of her parents in a car accident when she was little and asking the other students to be patient and charitable to her. She’s experienced this before, and she knows that, while the other students start off treating her charitably, they soon get tired of being charitable and start picking on her. Maggie tries to run away from the class, and that earns her a reputation as a weirdo right off the bat. The other kids immediately start treating her like a weirdo and calling her the usual nasty names, and Maggie’s only relief is that, this time, they didn’t go through the false kindness phase first.

Uncle Morris doesn’t live at the old school with the aunts, but he lives nearby and sometimes comes to visit. He continues to spout his witty nonsense and plays weird practical jokes that make no sense. Maggie starts to understand that her uncle’s form of teasing isn’t meant to be mean, unlike the kids at school, but none of it really makes any sense to her. His jokes are pointless, and he doesn’t respond to anything, even Maggie’s emotions, in a normal way, turning everything into some kind of bizarre joke.

Then, Maggie starts to hear voices in the house. She can’t tell where the voices are coming from, but she knows they’re not her aunts, and her aunts never seem to hear them. They talk about random things, like tea, roses, a lost umbrella, and a dog. Maggie asks her aunts who’s talking, but her aunts say no one is. They think that it’s just Maggie’s imagination because she’s highly strung, but Maggie knows that she’s not imagining it. Her Uncle Morris also seems to hear the voices because he reacts to them at one point, but when Maggie tries to ask him about it, he dodges the question and makes another of his nonsense jokes.

One day, while her aunts are out of the house, the voices call to Maggie and ask her to join them. Maggie searches for the source of the voices, and behind the wall in the attic, she discovers a small room with a pair of mysterious dolls who are alive. They walk and talk. At first, Maggie thinks this must be some kind of trick, but it isn’t. She tries to ask the dolls what they are, but they speak in nonsense jokes in response to serious questions, like Uncle Morris.

Maggie is unnerved by the dolls at first, and she throws a fit about how stupid their pretend tea party is, kicking the dolls aside in fear because she can’t understand them and is afraid of what they might do to her. The dolls simply conclude that they must have been wrong and that Maggie isn’t the right one and stop talking to her. Maggie tells them that she doesn’t care and doesn’t want to be the right one, but actually, she can’t stop thinking about the dolls. She wonders what they mean about the “right one” and what kind of person would be the right one. She also feels guilty about damaging the dolls when she kicked them, so she returns to the attic to fix them. When she starts to fix them, the dolls begin speaking to her again.

The dolls become Maggie’s friends, giving her the love she so desperately needs. Maggie also feels needed by someone else for the first time in her life, enjoying the feeling of taking care of the dolls, sort of the way she took care of the girls in her imagination. However, the dolls have a spooky origin, and when Maggie realizes the truth about the dolls, it changes her life forever.

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive (multiple copies).

My Reaction and Spoilers

About Maggie

I wasn’t sure if I was going to like this one or not because, while I like sort of atmospheric spooky themes, I have limits on how many scary and sad themes I can take. It did help that the book is divided into sections, each with a prologue about Maggie in the present day as she looks back on this strange period in her life. The prologues explain how Maggie is now in a happier home with people she has come to think of as her parents and younger children that she has also come to love as little sisters. The other kids are fascinated by the stories that she tells about her time with her aunts at the old boarding school, and Maggie enjoys explaining things to them, like she used to do to the imaginary girls, only she speaks more politely to the real girls. Since her time with her aunts, she has learned to get along better with people, and this ghost story is about how she learned how to build connections with people.

The book makes it clear that Maggie’s bad behavior is because she has been lonely, neglected, and mistreated since her parents’ deaths. She has been in various foster homes and boarding schools, but the people who were her caretakers didn’t really love her or have any patience with her. The other children in her boarding schools used her as a target for teasing and bullying, causing Maggie to look at everyone new she meets with suspicion, waiting for them to turn on her, even if they acted nice at first. The adults don’t really build a relationship with Maggie and just expect Maggie to be perfectly behaved, regardless of her provocation. Maggie remembers having spoken to psychologists before, who had her draw pictures of her feelings and family, but they never really solve anything for Maggie. Maggie still feels neglected and unloved, and when the adults at each place she’s been get tired of her, they just ship her off to somewhere else, where the process continues. Maggie’s bad behavior is like shooting herself in the foot, sabotaging possible friendships and relationships, but it becomes more understanding when you realize that this is the only pattern of relationships she knows. Children and adults have both mistreated her, so she doesn’t have any knowledge of healthy and loving relationships to draw on to know how people are supposed to treat each other.

That’s been Maggie’s life for as long as she remembers. The only clothes she has are old, worn pieces of various school uniforms from the various boarding schools where she’s been, and she has no toys or personal possessions except for a pack of cards that she uses to play solitaire, a game that one of her former boarding school roommates taught her. It’s the only game Maggie knows how to play other than imaginary games.

Maggie’s aunts and even her Uncle Morris aren’t particularly good for her. Her aunts have no patience or understanding for her. The aunts do care about Maggie. Maggie does become better fed and healthier because the aunts are concerned about her health, but they don’t understand how to take care of her emotional health. They also have some selfish motives in their care of Maggie, wanting to show off her improvement to their health society because they want to prove their health theories. Uncle Morris is quietly supportive of Maggie, but I found him rather trying because, when Maggie tries to speak to him seriously and sincerely, he just makes jokes and never really addresses her feelings or the realities of her situation. Admittedly, it’s partly because he knows the truth about the dolls but can’t admit it. Still, constant jokes aren’t what Maggie really needs, and his jokes and nonsense wear on her. The dolls also speak nonsense, but they give Maggie the opportunity to learn valuable lessons about how to get long with others and build relationships with them.

How to Build Relationships

One of the first lessons that Maggie learns is that, while other people have done things to hurt her, she also does things that hurt other people’s feelings. Before she can begin to develop relationships, she has to learn to control herself, to not treat other people in hurtful ways, and to apologize and do things to repair damage she’s done. She can’t begin to build a relationship with the dolls until she repairs the damage she did the first time she met them. Maggie is actually amazed that she was able to do it because she has never fixed anything in her life. She is unaccustomed to the idea that she can make things better when things have gone wrong or when she’s done something wrong. Most of her past problems have just ended in failure and with her being sent away.

Maggie also learns that building relationships with other people means caring about their needs, and Maggie likes the feeling of being needed by someone. Acting out the tea parties with an empty tea pot and wooden pieces of bread and watering the fake roses on the wallpaper is still ridiculous, but she does it all anyway because the dolls need her to do it. She gives them presents, too, the first presents that she’s ever given anybody. One of the girls at Maggie’s school, Barbara, sees Maggie making a present for one of the dolls and gives Maggie a little paper umbrella for a doll. Maggie learns that it’s possible for people to bond over shared interests.

What Are the Dolls Really?

However, there is a dark side to this story. There are hints all along about what the dolls really are. The man doll, Timothy John, is always reading a torn scrap of a newspaper about a fire, but he can never finish the story because most of it is missing. Every day is Wednesday for them, and they say that is the day they arrived in that room. When they show Maggie their best Sunday clothes, which they never wear because every day is Wednesday to them, Maggie is surprise to see that the clothes are burned. The dolls also speak of a third person who is supposed to join their doll household at some point, but they say that it can’t be Maggie because she’s supposed to be their visitor.

The truth is that the dolls are the ghosts of her ancestors, the ones who founded the school. They were killed in a fire in the 1800s, along with their dog, who is now a little china dog in their attic room. The story in the little newspaper scrap is about them, and the fire is the reason why the school had to be moved to another building. Maggie doesn’t realize the truth until she runs away after an argument with her aunts because she didn’t come to the party of their society and finds their grave stones. It’s the anniversary of their deaths, and she meets Uncle Morris at their graves. The only time Uncle Morris doesn’t make jokes is when he explains to Maggie how they died.

After the aunts catch her in the attic with the dolls and Maggie finds out who and what they are, the dolls stop moving and talking to her. Maggie tries moving them herself, acting out their tea party, and talking for them. Maggie is afraid that the dolls have now died forever, but there is the third person the doll spoke of to consider. The third person is Uncle Morris. It occurred to me that the story leaves it a little ambiguous about whether the dolls were really the ghosts of the ancestors or if Maggie’s own lonely imagination, inspired by Uncle Morris’s nonsense and bits of family history made her feel like they did. However, the ending of the story indicates that Maggie didn’t imagine any of it because her Uncle Morris dies of a heart attack and becomes a doll in the attic with the other dolls. When Uncle Morris joins the other dolls, the other dolls come to life again. However, it could still be the imaginings of a lonely and grieving child.

Maggie’s aunts decide that they simply can’t handle Maggie, so they are the ones who arrange for her to go to her new family. It was the best thing that they could have done for Maggie. The new family is the family that Maggie really needs, and they want to keep her permanently. She never tells her new sisters the truth about the dolls. Maggie misses being with the dolls, who are also her family, but the idea that they are still alive and that Uncle Morris is keeping the other two in the attic company so they won’t be lonely without her makes her feel better. It’s a bittersweet story.

One of the things that bothers me about ghost stories is that it’s sad to think about how the people got killed. I like stories that are kind of mysterious, but behind the ghost story, there is real tragedy. I feel really bad for Maggie’s ancestors and their poor dog, although they don’t seem to mind their condition too much. On the other hand, maybe some of their nonsense talk is to cover up the sad parts, so they can forget the tragedy and pretend like they’re still living their normal lives and make it so they don’t have to answer Maggie’s uncomfortable questions. Maybe that’s even where Uncle Morris learned that trick.

There are times when the dolls seem to have some memory of the past and what happened to them, but they’re kind of caught in a sense of timeless, so it’s hard to tell how much they really remember. If they really are ghost dolls and not just dolls who are alive in Maggie’s imagination, there’s no explanation about why they are dolls. Did they have dolls made of themselves while they were alive that they came to inhabit after death? Is it because they’re now playing at a life they’re no longer living? The story doesn’t say. Uncle Morris seems to know more than he tells, and he may have known somehow that he would also become a doll after his death. If he met the dolls himself when he was young, he may have made a conscious decision that he would join them one day. However, we don’t know for sure how much he knows or how or why the other dolls know to expect him after his death. Poor Maggie’s life has been about loss since the death of her parents. She lost them and her first home and every home she’s had since then. The idea that people she loves stay alive in the dolls could still be her imagination. The story indicates it’s all really happening, but readers can still decide for themselves.