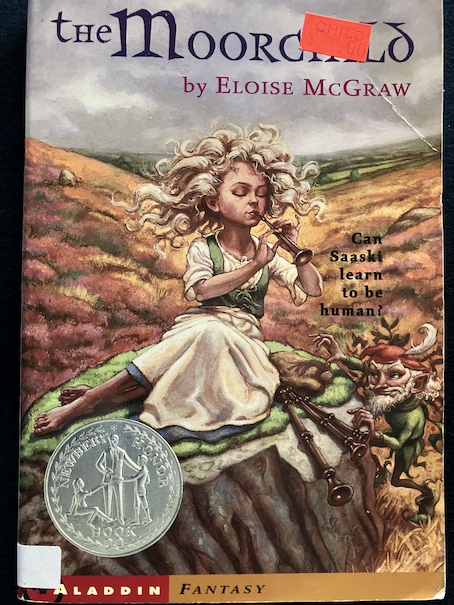

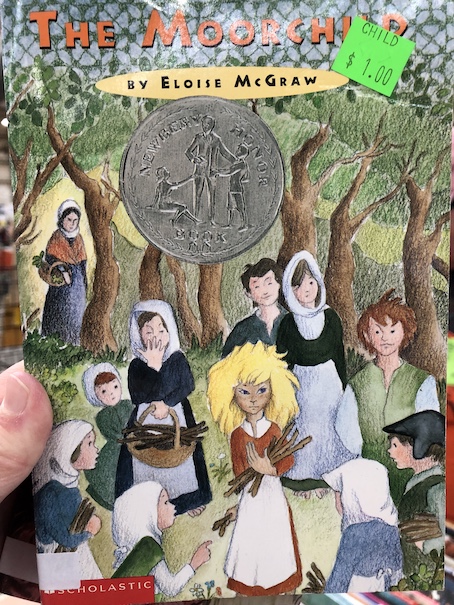

The Moorchild by Eloise McGraw, 1996.

When Saaski was only a few months old, her grandmother, Old Bess, started to notice that she didn’t look right, compared to the rest of the family or even compared to the way she looked when she was a newer baby. The grandmother tried to brush those thoughts aside, thinking that children change as they grow, and people of the village think that she’s odd herself as a widow who lives alone and knows about herbs. All the same, Saaski seems unusually fussy and throws tantrums, becoming a child who’s difficult to control. It could just be colic, or it could be something stranger.

Old Bess begins to put the pieces together about Saaski’s strange behavior. Saaski seems to hate or fear her own father, and Old Bess realizes that it’s because he is a blacksmith and wears an iron buckle on his belt. Saaski has an aversion to iron. She also has an aversion to salt, and only honey seems to soothe her. Saaski’s eyes change color from time to time, and Old Bess realizes that Saaski not only isn’t her grandchild but that she isn’t even human. Saaski is a changeling, a fairy child switched out for the human child before her christening.

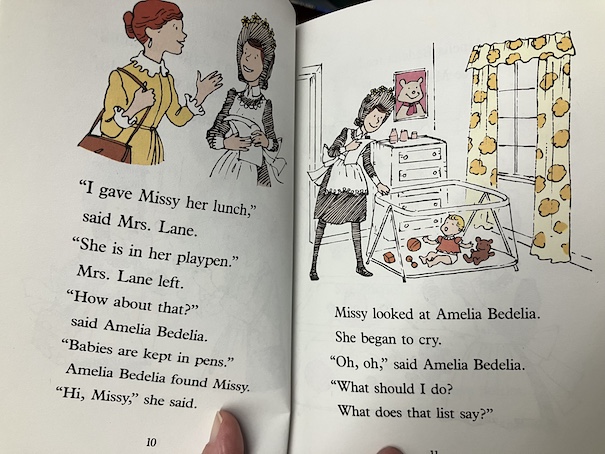

When Old Bess tries to tell her daughter and her husband that Saaski is a changeling, her daughter refuses to believe her. Her husband seems to consider that Old Bess might be right, but he absolutely refuses to do the cruel things to the child that Old Bess tries to tell them will cause the fairy folk to take the changeling back and bring them their real daughter. Old Bess says that Saaski must either be made to tell her true age, which she cannot do because she cannot talk yet, or the parents must do cruel things to her, like beat her, burn her, or throw her down a well. The parents say that they cannot do such things to a baby, no matter what kind of baby it is, and they no longer want to discuss the matter, forbidding Old Bess to tell anyone else of her suspicions.

However, in this case, Old Bess is correct. The child known as Saaski is a changeling, and she knows it herself. Although she is in the form of a human baby, she knows that she is not really a baby. Her fairy name was Moql. She doesn’t know her true age, but she knows that she is a fairy youngling and that she used to live among the other fairies in the fairy mound. She doesn’t like being part of this human family, and she wishes that the fairies would take her back, but she knows that, whatever happens, they never will reclaim her. Even if this family treats her cruelly and the fairies decide to remove her from their house, she knows that they will just place her with a different human family.

The problem is that, unlike other fairies, Moql has no ability to hide from humans. Other fairies can change their shape or color, fade, or just wink out of human vision entirely, but Moql can’t. The fairies discovered it one day when Moql was unable to hide from a human shepherd. She is able to escape from the shepherd, but her blunder isn’t forgiven by the other fairies. Moql’s inability to hide from humans was considered a danger to whole band of fairies. She was taken before the prince of the fairies. When he sees that Moql cannot hide from humans, he remembers that a human man entered the fairy mound some time ago and stayed awhile with a fairy woman. Moql’s mother was a fairy, but her father was that human. As a half-human, Moql will never have the abilities that the other fairy younglings have.

When Moql is considered a danger to the other fairies, they feel little attachment to her or desire to keep her. They don’t consider a half-human likely to work out among the fairies, so they decide to swap her for a human child who might make a good servant to the fairies. They’ve done this before with other younglings like Moql. Moql is frightened because she doesn’t know how to be human. Life in the fairy mound is all that she knows. She is only half human, and if she’s not working out as a half fairy, how can she possibly work out as a human? What if she can’t work out as a human? Will she belong anywhere? What if she belongs nowhere?

The fairies tell her that she will start life all over again as a human baby and that she will forget all about the mound and her past life. The other fairies think nothing of casting her out. None of them really care about her. The fairies don’t feel emotions like humans do, and they don’t feel very much about anybody. Moql’s birth mother doesn’t feel anything for her but a mild curiosity and no concern for her future. Fairy mothers don’t really develop an attachment to their children, who are raised communally in the fairy nursery and school. Most fairies don’t even know who their parents are, and they don’t really develop feelings for their parents any more than parents feel attached to their children. Even fairy couples don’t stay together very long, forgetting about each other when they become bored with the relationship and moving on to others. Fairies don’t really care that much about relationships, like brother and sister, and fairies don’t even have a sense of what being a “friend” means. So far, even Moql hasn’t felt that much for anybody, either. Moql’s first human feelings come with her despair about being torn away from everything and everyone she’s ever known, made worse from realizing that nobody else feels anything for her. In their position, she might not feel anything for the loss of one of them because that’s the fairy way, but the human part of Moql longs for belonging and fears what will happen to her if she can’t find a place or people to belong to.

When Moql wakes the next day, she finds herself as the baby Saaski, but in spite of what the fairies said, she still retains her memories of her fairy life. Everything in this human household is strange. She fears the people who are supposed to be her parents, and most of the things that they offer her to soothe her aren’t soothing to a fairy or half-fairy, which is why she screams and throws tantrums. When she hears Old Bess describe her as a changeling and tries to urge her parents to do things to get rid of her, Moql realizes that she is stuck as a human, no matter what happens. Her only hope is to make herself forget or at least pretend that she doesn’t remember being a fairy and to try her best to be the human baby Saaski. It means pretending that she doesn’t have the ability to do things that a human baby shouldn’t be able to do and that she doesn’t know things that she actually does know. It’s not easy, but Saaski’s memories do fade a bit with time. She has vague memories of her past life, but the longer she lives as a human, the less she remembers of her past.

Time passes, and Saaski grows into a child, but the humans around her have an odd feeling about her. They whisper about her behind her parents’ backs. She doesn’t look like other human children, and odd things seem to happen around her. Saaski doesn’t trust Old Bess because she knows that Old Bess has always suspected she was a changeling. Other children in the village have heard their parents whispering about Saaski, and they start asking her if she really is a changeling. By that point, Saaski isn’t sure anymore what that means.

Old Bess does look for an opportunity at first to get the fairies to take back the changeling, considering shoving her into a pond at one point. However, when she realizes that Saaski has real feelings, she cannot bring herself to do it. She realizes that Saaski is also a victim of the switch when she was exchanged for the real Saaski. She doesn’t really belong among them, Saaski knows it, and Old Bess can tell that it hurts that she’s different and that others don’t accept her. Old Bess isn’t sure how much she understands about herself, her past, or her situation, but it’s been as unfair to her as it has been to the real Saaski and her family. The sense of belonging Saaski craves eludes her.

The only place Saaski really feels at home is out on the moor by herself, although she doesn’t really remember why anymore. That is where she first meets the orphan boy, Tam, who travels with the tinker. Tam knows what other people say about Saaski, but he isn’t afraid of her and likes her anyway. He is the first person who really seems to accept Saaski. For a time, her father forbids her to go on the moor again after she has a distressing encounter with a shepherd, who seems to recognize her as being a fairy.

Surprisingly, Old Bess turns out to be an ally of Saaski’s, urging her parents to let her go to the moor again. She knows how restless Saaski has been, confined to their home. The only thing that has soothed her is the old bagpipes that once belonged to her father’s father. She seems to know how to play them without anyone ever teaching her. Eventually, her parents allow her to return to the moor, partly so she won’t keep playing the bagpipes at home. When she’s able to see Tam again, he is happy to see her, and she shows him how she can play the bagpipes.

There are other things that Saaski seems to know without knowing how she knows. She sometimes sees strange symbols that no one else seems able to see. When Old Bess realizes that she can see these symbols, called runes, the two of them discuss it. Old Bess can’t see them herself, but she knows about them. She learned a lot about such things from an old monk she once cared for and from the books he left behind, which is also where she gained her knowledge of herbs.

Old Bess admits to Saaski that, like her, she is considered strange and that she doesn’t quite belong to the village where they live. She was brought to the village as an infant after she was found abandoned in a basket at a crossroads. They left her at the miller’s house, and she was raised by the miller and her wife. She doesn’t know who her birth parents were, where they came from, or why she was abandoned as an infant, and she was told that the gypsies who found her almost drowned her as a changeling before deciding to leave her in the village.

Saaski also knows that she doesn’t belong in the village, although she can’t think where she does belong. She can’t explain how she is able to see and understand fairy runes or do the other things that she seems able to do, apparently without anyone teaching her. Over time, she gradually discovers or rediscovers the things she could do and knew as a fairy. She discovers that she can see fairies when she spots one stealing Tam’s lunch. Later, a group of fairies try to steal her bagpipes. To Saaski’s surprise, she is able to understand their language, and they seem to recognize her.

Then, after the children in the village bully Saaski again, an illness comes to the village, afflicting all of the children but Saaski. Old Bess says it’s a normal childhood illness she’s seen before, and the children probably got it from the gypsy band who recently passed through town. However, the villagers, who have always been suspicious of Saaski whisper that Saaski is responsible, that she has cursed the other children. Saaski denies is, but the villagers are becoming increasingly hostile. They want her out of the villager, but if Saaski can’t stay there, where can she go?

When Saaski tries to bargain with a fairy for some help to hide from the villagers, the fairy reminds her that she was a fairy herself and that she was never able to disappear. Saaski is stunned at this confirmation of the villager’s suspicions about her being a changeling. When she tells Old Bess about it and about the memories that are now returning to her, Saaski realizes that she really doesn’t belong in this human village, at least not fully. Yet, she remembers that she doesn’t fully belong among the fairies, either. Once again, it leaves her the question of where she does belong. Saaski is going to have to take her fate into her own hands, but before she does, she wants to do something for the family that raised her and has loved her, in spite of everything: find the original Saaski in the fairy mound and return her to her parents.

The book is a Newbery Honor Book.

My Reaction

I enjoyed the story because it is a unique portrayal of the folkloric idea of changelings. Another book I read on the same topic, The Half Child, is told from a real world, historical point of view, without fantasy. In that book, changelings are disabled children or children who aren’t “normal” in some way who are labeled as being something other than human or “real” children because people of the past couldn’t understand why they were different or what was wrong with them.

The Moorchild, however, is fantasy and builds on the folklore concept. In other books with changelings, we see the changelings from the point of view of other people, who wonder about their true nature, but this book includes multiple viewpoints, including that of the changeling herself. In folklore, it isn’t entirely clear why the fairies would want to change their children with human children, leaving them to be raised by other people and possibly never seeing them again. This book builds on that concept, portraying the changeling children as being half human and/or flawed in some way, compared to the other fairies. They do use the human children they gain in the swap as servants, which is a folkloric concept, but this story explains why the fairy child left in exchange for the abducted human child is an acceptable loss to the other fairies.

Fairies in this story don’t have the same types of feelings as humans. In fact, they don’t seem to feel much at all, making most of their lives literally care-free because they just don’t care that much about others or the consequences of their actions. However, they don’t feel much emotional attachment to each other, either. Saaski/Moql’s birth mother doesn’t feel much of anything for her daughter or for the man whose life she changed and worsened through her seduction and rejection. She is completely unconcerned about what has happened to them or what will happen to them because of her. Later, Saaski realizes that the fairies are aware that Saaski is blamed for pranks they played, but they don’t mean it spitefully. They genuinely don’t care whether Saaski or someone else is blamed for things they do as long as they never get caught themselves. When Saaski realizes that the other fairies genuinely don’t care about her or what happens to her, she knows that they will never take her back and that she will never rejoin them.

Saaski feels more emotion than full fairies feel, but she doesn’t always respond in acceptable or predictable ways to the humans she lives with because she doesn’t share all of the emotions they feel. She craves a sense of belonging, but she doesn’t really know how to get it or create it. At times, she feels love and gratitude without being entirely sure what she’s feeling or how to express it. Strangely, she also doesn’t experience hate and resentment in the same way humans do. Tam tries to explain it to her, and Saaski recognizes that the children in the village who bully her feel hatred and resentment to her, but she doesn’t feel those emotions herself. She doesn’t like it when they bully her, and she feels hurt by them, but the emotion of hating and wanting to hurt them back isn’t there. I thought that was an interesting concept, exploring someone with non-conforming emotional reactions. Saaski’s emotions in the story are explained by her fairy heritage, but what made it interesting to me is that neurodivergent humans also have different ways of experiencing and showing emotions that can change the way they are accepted by or interact with other people, which brings the idea of changelings full circle, back to the concept of children who aren’t like other children from birth or a young age.

I thought it was fascinating that we get to see things both from Saaski’s point of view and from the point of view of other people, particularly Old Bess. Old Bess is the first to realize that Saaski is a changeling and not her “real” granddaughter. She understandably wants her real granddaughter back, and she knows the folklore that fairy folk will take back a changeling who has been abused. However, Saaski’s parents, even knowing or suspecting that Saaski might be a changeling, cannot bring themselves to do anything cruel to her, and Old Bess comes around to that point of view herself. By observing Saaski, she sees that Saaski is a child, if not an entirely human child, and an innocent victim of the switch herself, with feelings and a difficult life ahead of her because she doesn’t fit in with this community.

Old Bess also recalls and admits to Saaski that her own past isn’t quite normal and that she also doesn’t quite fit in. I wondered if we would ever get the full story of Old Bess’s past, but unfortunately, we don’t. We know that she was abandoned as an infant, apparently rejected by her birth family or guardian, but we never learn why. I had wondered at first if Old Bess would turn out to be a grown-up changeling. It seems that people once suspected that about her, but apparently, she isn’t because she can’t see the fairies or fairy writing in the way Saaski does. It seems that Old Bess is fully human and not half fairy. In the end, the important point is that, when Old Bess is honest with herself and Saaski about her past, her story has some elements in common with Saaski’s situation. They have both known rejection and abandonment, the difficulties of trying to fit in when they don’t entirely fit in, and the love of people who accepted them and cared for them in spite of it all.

I appreciated that Saaski’s parents do their best to love and care for Saaski even when they know she’s strange and may not be their daughter. They stand up to the people who bully their daughter and pressure them to get rid of her. In fact, in the end, even after Saaski and Tam set out into the world together and they have their birth daughter back, they still think of Saaski and miss her sometimes. Saaski was no replacement for the daughter they lost when they were switched, but at the same time, they realize that their birth daughter doesn’t entirely replace Saaski in their lives and affections. In the end, it’s like they’ve had two daughters, both of them “real”, although one didn’t fit in and eventually left to start a new life elsewhere.