Kiki’s Delivery Service by Eiko Kadono, English translation by Lynne E. Riggs, 1985, 2003.

More Americans would probably recognize the title as the title of a Studio Ghibli animated film for children than as a book title, but the book came before the movie, and it is actually the first in a series, which continues the story about Kiki’s life and adventures, although I don’t think the later books in the series have been translated into English (at least, I haven’t found them in English). The original Japanese version of this book was written in 1985, and I read the English translation from 2003.

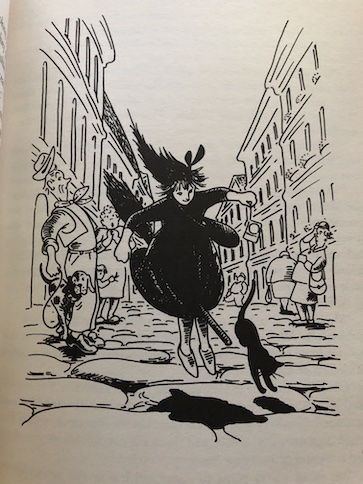

Kiki is a young witch, and in keeping with the traditions of young witches, she is expected to leave home at age 13 and live for a year in a city with no other witches. It will be a test of her developing skills and a coming-of-age experience, helping her to recognize her talents and find her place in the world.

When Kiki sets out for her journey with her cat, Jiji, she doesn’t know exactly where she is going to go or what she will find when she gets there. Some young witches know early on what their talents are and how they plan to support themselves during their year away from home, but Kiki is less sure (like so many of us who “don’t know what we want to be when we grow up”). The term “witch” just refers to a person’s ability to do magic. It’s not a job title by itself, and witches are expected to develop a specialization, such as brewing potions or telling the future. Kiki’s mother has tried to teach Kiki her trade, growing herbs and making medicines from them, but Kiki hasn’t had much patience with it. The only major ability Kiki has is flying, which is something that witches are expected to do anyway. Still, she has an adventurous spirit and is eager to set out and see what life has to offer.

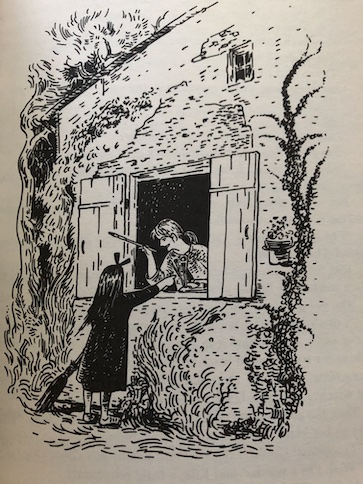

Once Kiki locates a city with no other witches, she has to find a place to stay and a job to earn money. She finds a city by the sea, which seems exciting to her. As she explores the city, she meets Osono, a woman who owns a bakery with her husband. When she helps deliver a baby’s pacifier to a bakery customer who left it behind, flying to the customer’s house on her on her broom, Osono offers to let her stay in a small apartment attached to the bakery. Kiki feels a little overwhelmed by the big city at first, but she realizes that, in a large city like this, there are probably a lot of people who have small delivery errands that wouldn’t be covered by ordinary parcel delivery services.

Kiki opens a delivery service, delivering small packages and running errands for people around the city. At first, business is slow, and some people are afraid of her as a witch. During a trip to the beach, a curious boy borrows her broom and breaks it. Kiki is distressed, and the boy apologizes. The boy’s name is Tombo, and he is part of a club of other kids who are interested in flying. He has made a study of flight and had hoped to learn more about how witches fly by trying Kiki’s broom, but Kiki expains that only witches can fly with brooms and that the ability is inherited. Kiki has to make a new broom, and it takes her a while to break it in, but it actually works to her benefit. People who were initially afraid of her for being a witch become less afraid of her and more concerned about her when they see that she is just a young girl, clumsily trying to master a new broom. Kiki gets some additional support and business from people who feel moved to help a struggling young witch. Tombo also makes it up to her and becomes a friend when he helps Kiki to figure out a way to carry a difficult object on her broom.

During her very first delivery assignment, Kiki was supposed to carry a toy cat to a boy who was having a birthday, but she accidentally dropped it. When she searched for it, she met a young artist, who was enchanted by Kiki as a young witch and painted a portrait of Kiki with Jiji. When the artist asks Kiki to take the painting to the place where it will be on exhibit, Kiki isn’t sure how to carry it at first. It’s kind of a bulky object to carry on her broom. Remembering that Tombo has made a study of flying, she asks him for help. Tombo ties balloons onto the painting to make it float and tells Kiki that she can now pull the painting along on a leash, as if it were a dog. The idea works, and when people see Kiki pulling a painting of herself along through the sky with balloons tied to it, it acts as advertising, bringing her more business.

Some of Kiki’s new jobs are difficult or awkward, and some customers are more difficult to deal with than others. There are times when Kiki finds herself missing home or trying to remember how her mother did certain things, wishing that she had been better at watching and remembering what her mother did. Still, Kiki learns many new things from her experiences and acquires new skills.

Kiki’s experiences also help her to realize a few things about herself and life in general. Like other girls, Kiki worries about how boys see her. When Tombo makes a comment that he can talk to her when he can’t talk to other girls, Kiki worries that he doesn’t see her as a girl at all. A job delivering a surprise present to a boy from another girl her age helps Kiki to realize that everyone is a little shy and uncertain about romance and even people who act confident feel a little awkward about first relationships.

As her first year away from home comes to an end, Kiki wonders how much she’s really changed over the year. Although she has successfully started a new business and done well living away from her parents, she still experiences a sense of imposter syndrome, where she doesn’t quite feel like she’s really done all of the things she’s done. Her first visit home to her parents reminds her that her new town has really become her new home. She has become a part of the place, and she feels her new business and friends calling her to return.

In 2018, the author, Eiko Kadono, was awarded the Hans Christian Anderson for her contributions to children’s literature.

My Reaction

I think of this story as one of those stories that takes on more meaning the older you get. Young adults can recognize Kiki’s struggles to make her own way in the world and establish herself in life as ones that we all go through when we start our working lives and gain our first independence. It can be a scary, uncertain time, when we often wonder if we really know what we’re doing. (Life Spoiler: No, we don’t, but no one else completely does, either, so it’s normal and manageable. Some things just have to be lived to be really understood, and that’s kind of the point of Kiki spending a year on her own, to see something of life and how she can fit into it.) However, it’s also a time of fun and adventure as we try new things, build new confidence, make new friends, and learn new things about ourselves. Like so many of us, Kiki doesn’t always do everything right, but she learns a lot and endears herself to the people of her new town.

The Miyazaki movie captures the feel of the story well, although the plot isn’t completely the same. There are incidents and characters that are different between the book and the movie. Tombo appears in both the book and the movie, but there are other characters who appear in the book who weren’t in the movie. In the book, Kiki makes friends with a girl named Mimi, who is her age, and the two of them discuss crushes on boys and how each of them was a little envious of the other because, while each of them is struggling with their own uncertainties in life, they each thought that the other acted more confident. The movie version developed the character of the young artist more. Kiki also didn’t lose her powers during the book, although that might be a part of one of the other books in the series, since I haven’t had the chance to read the others yet.