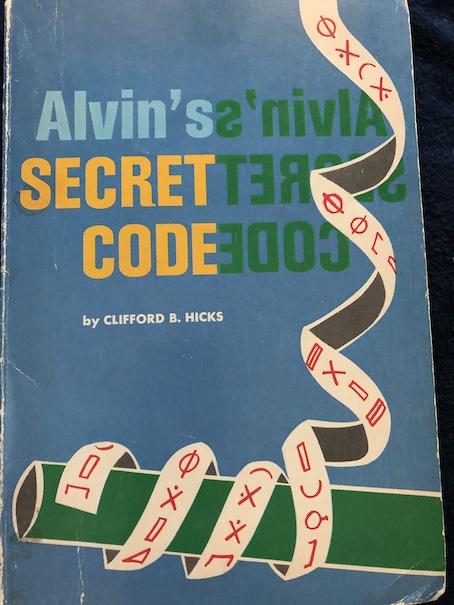

Alvin’s Secret Code by Clifford B. Hicks, 1963.

This book is part of the Alvin Fernald series.

Alvin has been reading a book about spies, and now, he and his best friend, Shoie (a nickname, his real name is Wilfred Shoemaker), are playing at being spies. One day, as the boys are walking home from school, Shoie stops to pick up another bottle top for his collection, and he finds a scrap of paper with a strange message on it. The words in the message don’t make any sense, and it looks like it’s some kind of secret code.

When Alvin gets home, his mother insists that he clean his room before he does anything else. Shoie helps him, and Alvin’s little sister, Daphne, insists that she wants to help, too, because she wants to see what the boys are doing. Daphne is fascinated by the things her older brother does and always wants to be included. When Daphne finds out that they’re being spies and have found a secret message, she also insists that she wants to be a spy and look at the message with them. They let her see the message, but they insist that she can’t be a spy because it’s dangerous and “work for men.” (That attitude comes up in mid-20th century kids’ books, especially ones for boys. I’d just like to point out here that, while dealing with spies would actually be dangerous, too dangerous for a young kid like Daphne, the fact is that both Alvin and Shoie are only twelve years old, so technically, they don’t count as “men”, either.) At first, the kids think maybe the message is meant for a secret Russian spy ring targeting the nearby defense plant. (This book was written during the Cold War, so that would be one of the first possibilities they would consider.)

Alvin comes to the conclusion that they need to investigate Mr. Pinkney, a relative newcomer to their town, because they found the message near his house, the message mentions an oak, and there’s one growing nearby. Alvin also thinks that they might need some help to break the code in the message, so he suggests that they visit Mr. Link, a WWII veteran who was also a spy during the war. He’s now an invalid who has a housekeeper who takes care of him, but he could still advise them about what to do with the mysterious message. Although the boys tell her that she can’t be involved with what they’re doing, Daphne still tags along with them when they go to see Mr. Link.

When the kids ask Mr. Link about his time as a secret agent during the war, he calls spying a “dirty, dirty business” but “something that must be done”, saying that he’s glad that it’s all over now. However, he’s perfectly willing to talk about secret codes and ciphers. Mr. Link has even written a couple of books on the subject. This story is a nice introduction to codes and ciphers for kids because it explains some of the terms and how codes and ciphers work. As Mr. Link points out, much of what people think of as secret codes are actually ciphers. The difference is that ciphers are actually secret alphabets that can be used to compose messages. When Mr. Link asks them if they’re trying to compose a cipher themselves, the kids tell him about the secret message and their suspicions that there could be a spy in their town.

Mr. Link doesn’t reject the possibility that there could be a spy in the area, but he tells them that they’re wrong to suspect Mr. Pinkney of being a spy because Mr. Pinkney is a friend of his, and he knows him very well. For a moment, Alvin wonders if they should suspect Mr. Link too, but Mr. Link anticipates the thought and says that he can prove that he’s trustworthy by telling them more about Mr. Pinkney and breaking the code for them. Mr. Link explains that Mr. Pinkney was lonely when he first came to town, and that’s how the two men started playing chess together regularly. Mr. Pinkney owns a factory that makes electronic devices, like transistor radios and intercoms, and one day, he told Mr. Link that he had a problem with his business. He suspected a business spy of trying to intercept his messages to his product distributors in Europe, and he needed a way to make his messages more secure. Naturally, Mr. Link suggested using a code, and he recognizes the coded message the kids found as one that Herman Pinkney sent to his distributors. Mr. Link shows the kids how each word in the strange message stands for another word or concept. Only someone who knew what the code words were supposed to mean would be able to read it.

Alvin is a bit embarrassed about jumping to the wrong conclusion, and Mr. Link says that he’s learned a couple of important lessons from this experience. First, you shouldn’t jump to conclusions about people if you don’t know them very well, and second, people who are full of tricks and deception are easily confused when they encounter straightforward honesty. In other words, while Alvin was spinning imaginative spy tales in his head, he overlooked the possibility that there could be a more innocent explanation. Alvin is still embarrassed, but he takes the lessons to heart, and Mr. Link tells them more about codes, how they have been used in history, and how codes are around them all the time, every day.

I liked Mr. Link’s explanations about how codes aren’t just for spies. He says that codes are used for all kinds of communications where only certain people are meant to read and understand messages. He explains about the product codes on things that the kids buy and wear everyday, showing them how to read the size codes on their shoes. Codes can indicate where and when products were made, and we still use product codes for that purpose in the 21st century. I used to work in a textbook store, and we used the codes on textbooks to tell which edition of a book students needed or whether a student needed just the textbook or if they needed books that came bundled with other, supplemental materials. Mr. Link says that ordinary people can sometimes figure out what product codes mean by studying them and looking for patterns that they recognize, like dates or sizes.

Since this book was written in the 1960s, they don’t talk about computers or the Internet, but that’s a major use of codes in the 21st century, and anybody can study and learn computer coding. Computer programming involves “coding” because, like with the other codes that Mr. Link describes, programming languages are also codes, using certain words and symbols to represent concepts that not everybody needs to read in order to use a computer, but which the computer can interpret so it knows what the programmer and user want it to do. Communications and transactions over the Internet also involve cryptography to protect the users’ information, using algorithms to convert a sender’s plaintext message to ciphertext to conceal its true meaning from any third party who might try to read the message and then back into plaintext so the intended recipient can read it. Codes really are around us all the time, even when we’re not fully aware of them or paying close attention to them.

The kids are fascinated by Mr. Link’s stories about how codes were used in history and the unusual methods people used to send secret messages, like writing them on someone’s head and then letting their hair grow out and cover it. He also shows them scytales, round pieces of wood that can be used for reading secret messages. The message would be written on a long strip in what appears to be jumbled letters. The message only makes sense when the strip is wrapped around the scytale so that the letters will align in the proper order to be read. That’s what’s shown on the cover of this book, although the picture also shows a message written with code symbols.

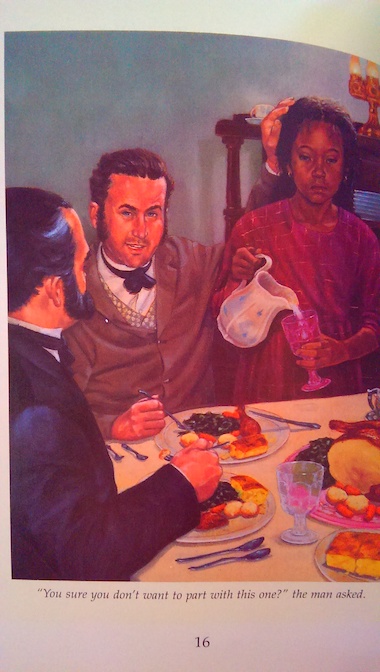

It’s all fun and games until a woman named Alicia Fenwick shows up in town with a puzzle that puts the kids’ abilities to the test. She comes to see Alvin’s father in his professional capacity with the police, looking for a man named J. A. Smith. Miss Fenwick explains an incident that happened to her family during the Civil War. The Fenwicks used to own a Southern plantation with slaves. (Daphne says that she doesn’t like the part of the story about the slaves, and Miss Fenwick says she doesn’t either although her great-great grandfather was apparently kind to his … which is what they all say, isn’t it? More about that in my reaction section below.) During the Civil War, her great-great grandfather was an old man. All the young men went away to fight in the war, but he stayed at home. When there were rumors of marauding bandits, he got worried that the plantation with would be a prime target for them with all the young men gone. He enlisted the help of a former slave he had freed before but who was still a friend to help him hide the Fenwick family’s valuables. They put everything they could into a chest and buried it. Unfortunately, when the bandits came, they forced the former slave, Adam Moses, to reveal the location of the chest by threatening to kill his young son. After they dug up the chest, they took Mr. Moses prisoner and forced him to help them take the chest with them further north. Eventually, Mr. Moses escaped from the bandits after they tried to kill him, and he wrote a letter to the Fenwicks saying that he was now in Indiana and that the bandits had forced him to help them rebury the chest. He said that he would try to retrieve the chest and return home with it, but sadly, he was later found murdered close to Riverton, the town where the children now live, probably killed by the same bandits who took the chest. However, the leader of the bandits was also killed shortly after that, so they never enjoyed their ill-gotten gains. The treasure chest was never recovered. The story was passed down in the Fenwick family for generations as an unsolved mystery until recently, when Miss Fenwick received a letter from J. A. Smith asking her for any information she might have about about the treasure. She told this person about the letter from Mr. Moses but didn’t hear from him again, so she’s trying to trace J. A. Smith and find out what he knows about the treasure.

Sergeant Fernald, Alvin’s father, says that there are people in town with the last name of Smith but nobody who has the initials “J. A.”. However, the kids say that Miss Fenwick’s story might explain some of the stories told by local kids about an area outside of town called Treasure Bluffs. Rumor has it that there was a treasure buried there years ago, although nobody knows exactly why or where. The kids start to think that the story really points to the location of the Fenwick treasure, but the bluffs cover a lot of territory, and before they can really search for the treasure, they have to find a way to narrow down the search area.

The kids’ new lessons in code-breaking pay off when they spot a man at the local library using the code books that Mr. Link donated. The strange man is trying to break a message that will reveal the secret hiding place of the Fenwick treasure. Can Alvin and his friends figure out who the man is and break the code themselves before he does?

The book ends with a section explaining more about codes and ciphers. One of the codes they explain is the pigpen cipher, which is a popular one for children and appears in other children’s books. This book says that it was used in the Civil War, which is true, but it’s actually older than that.

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive.

My Reaction and Spoilers

There are some elements in this story about boys thinking that they’re more capable than girls, like in the way that Alvin and Shoie talk to Alvin’s little sister, but Alvin also acknowledge, to his irritation, that sometimes Daphne thinks even faster than he does. When Mr. Link is explaining the size codes on the children’s shoes, 8-year-old Daphne actually catches on a little faster than 12-year-old Alvin and comes up with the answer to a problem Mr. Link poses before Alvin’s “Magnificent Brain” does. I liked that touch of imperfection on Alvin’s part and the acknowledgement of Daphne’s abilities, which help thwart any overconfidence or arrogance that Alvin might have about his “Magnificent Brain.”

I appreciated that, although Alvin is clever, he’s not a complete genius, and he is noticeably fallible. He’s not good at everything, like some heroes of children’s books. He is terrible at spelling, and when he tries to write that he’s a cryptographer, he spells it “criptogruffer,” which doesn’t inspire professional confidence. Daphne knows the correct spelling and spells it aloud for him, much to Alvin’s embarrassment and annoyance. Alvin is still pretty clever, and he breaks the final code that reveals the hiding place of the treasure, but it is nice that he’s not unbelievably perfect.

The final code in the book is easy enough that anybody could actually break it with minimal effort. I spotted it pretty quickly because there’s something that I always do with secret messages in books, and it often pays off. (There are one or two things in the Harry Potter books that this works on as well.) I’m not going to spoil it here, although I’ll give you a hint: When I was a kid, I read and liked a book about Leonardo Da Vinci.

I genuinely enjoyed the parts of the story about codes, which run through most of the book. Mr. Link is full of helpful information, and the section at the back of the book with more information about codes is a nice introduction to some basic types of codes. As I said above, I like the practical applications of the lessons, showing kids how they can read parts of product codes, if they understand what to look for. That’s a useful skill, and you can use similar techniques to interpret the expiration dates on food products when they’re only stamped with a code instead of an explicit date.

Like Daphne, I also didn’t like the part of the story about slaves. This book was written during the Civil Rights Movement, which makes its takes on the Civil War, slaves, and race interesting. The author wants to tell a story that bears on the Civil War, so he has to address this is some fashion, and he tries to get pass the uncomfortable issue of families owning slaves as quickly as he can to get to the adventure part of the story.

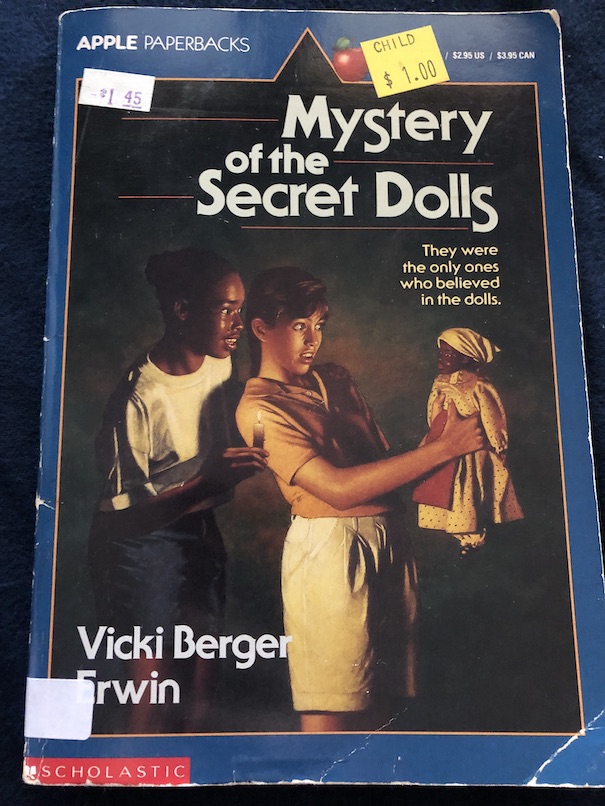

The Civil War and its associated legends of battles, ghosts, secret passages, hiding places, hidden treasures, and secret messages are staples of American children’s literature. It’s completely understandable because the Civil War was a major event that shaped life and history in the US, it was a traumatic event whose impact is still felt even into the 21st century, and it gave rise to many stories and legends that have further helped shape our culture. The idea of treasures hidden during the war and later forgotten is a popular trope and so are coded messages that point to secrets from the past. I’ve seen these tropes used in other children’s stories, like The Secret of the Strawbridge Place, The House of Dies Drear, and Mystery of the Secret Dolls, and they’re always fun. However, stories with a Civil War backstory can sometimes feel a little uncomfortable because they’re almost impossible to tell without involving slavery in some way because slavery was at the heart of the war.

When Daphne says that she doesn’t like hearing about slavery and owning slaves, they deal with the issue quickly, with Miss Fenwick saying she doesn’t like it, either, and adding that her great-great grandfather was apparently nice about it, and then continuing with the story. As I said above, yeah, right, that’s what they all say. In stories (and sometimes real life), when there are characters whose families owned slaves and plantations, they almost always add the idea that, while slavery was bad and horrible and slaves were mistreated elsewhere, this particular family was special and treated their slaves with kindness, and it was almost like they were one big, happy family. Yeah, right. To be honest, I probably would have accepted that as a kid and let it pass. As an adult, I’m not letting it pass without at least a few pokes in the side as it goes.

The idea of the grateful slave or ex-slave who loves the family he served has been a trope since the anti-Tom literature of the 1850s. I can’t swear that no slave never felt any kind of affection for members of the family that owned them because human nature is varied and unpredictable, surprising relationships can spring up, and if all else fails, Stockholm Syndrome also exists, so I suppose it could happen, but at the same time, I just don’t buy that whole “slavery is bad, but my family is kind, and our slaves loved us” type of narrative. Even if a given slave-owning family was “above average” in treatment of slaves, that doesn’t mean that they were “good” so much as “less bad” among a group of people perpetrating something bad. The “average” in this situation is so bad that there’s quite a lot above that level that still wouldn’t qualify as good, whether the descendants of slave owners believe those old school textbooks promoted by the United Daughters of the Confederacy (some of which were still in use during the Civil Rights Movement – children are shaped by the things they read and the people who gave them those books, and history is not written by the “winners” but by the people who write) or have really thought this through all the way or not. (You don’t have to take my word for it. You can hear about it from people who actually were slaves.) I suppose I can suspend my disbelief about this fictional family for the sake of this kids’ story, which is mostly about secret codes and a treasure hunt and spends little time on racial issues, but I’d just like to point out that I definitely do have a sense of disbelief about this that requires suspension.

Of course, I can see why the author had to include it. In order for us to be invested in the treasure hunt and care about the Fenwick family getting their fortune back, we have to believe that they’re great people, sort of removed or distanced from the responsibility for choosing to own slaves (“in those days, it was accepted throughout the South” is the only explanation we’re given), who were as kind to their slaves as possible, so kind that at least one loved them so much that he gave his life attempting to recover the family fortune, and that they will now use the treasure for some beneficial purpose. (We are told that the family now operates an orphanage, which badly needs money, although we’re also told that one of their former charges has since become a US Senator, so you’d think he could help raise some.) If we didn’t like this family at all, we might see the fortune that came from their plantation as the ill-gotten goods of exploiting someone else’s labor, its loss as poetic justice, and the profit from its recovery as probably something that should either go toward the slaves who did the work on the plantation or maybe some public cause, like a museum or something.

We are told that Adam Moses’s son survived the experience with the bandits, escaped from them when his father was captured, and was adopted by another family, but we are not told anything further about his descendants. While I was reading the book, I halfway wondered if a descendant of the Moses family would surface with some important clue to the situation and get some acknowledgement, but that doesn’t happen. Instead, there’s a person who’s related to one of the bandits, who thinks that he has a right to the treasure because his ancestor stole it from someone else. The characters in the story scoff at that logic, but when I consider the full context of the situation, it makes me think.

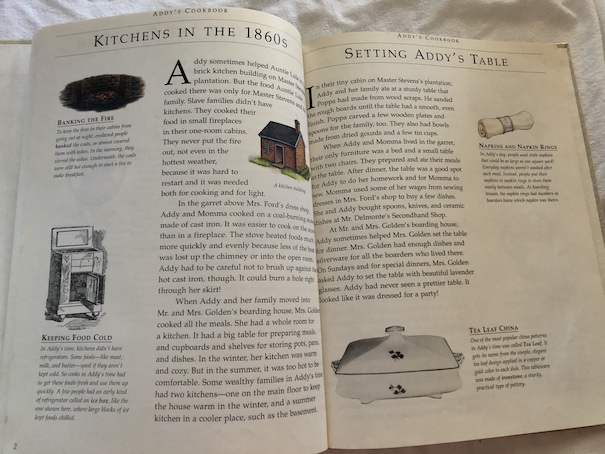

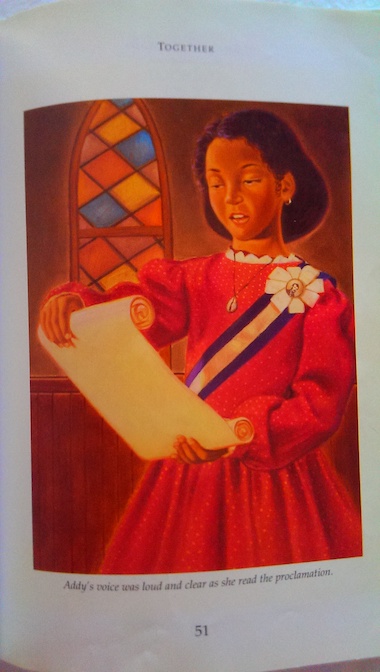

However, Auntie Lula does get to spend a little time with the family before her death, and she tells Addy not to be sad. People don’t always get everything they want in life, but they can take some pride in what they do accomplish. Lula and Solomon may not have gotten everything they wanted in life, not having had much time to enjoy being freed from slavery, but they did get to accomplish what was most important to them. Solomon died knowing that he was a free man, far from the plantation where he’d been a slave. Lula managed to reunite Esther with her family. From there, Lula says, she is depending on the young people, like Addy and her family, to make the most they can of their lives, hopes, and dreams.

However, Auntie Lula does get to spend a little time with the family before her death, and she tells Addy not to be sad. People don’t always get everything they want in life, but they can take some pride in what they do accomplish. Lula and Solomon may not have gotten everything they wanted in life, not having had much time to enjoy being freed from slavery, but they did get to accomplish what was most important to them. Solomon died knowing that he was a free man, far from the plantation where he’d been a slave. Lula managed to reunite Esther with her family. From there, Lula says, she is depending on the young people, like Addy and her family, to make the most they can of their lives, hopes, and dreams.

After escaping from slavery,

After escaping from slavery,

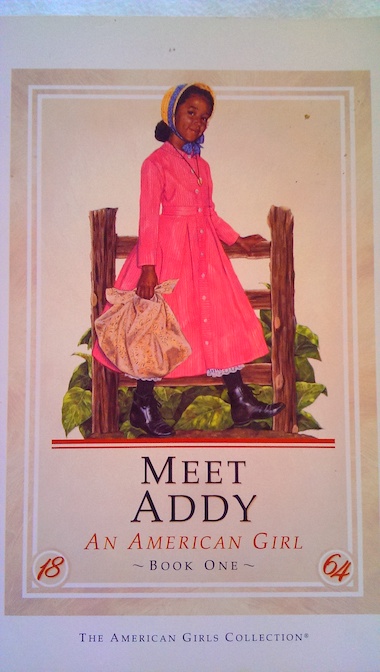

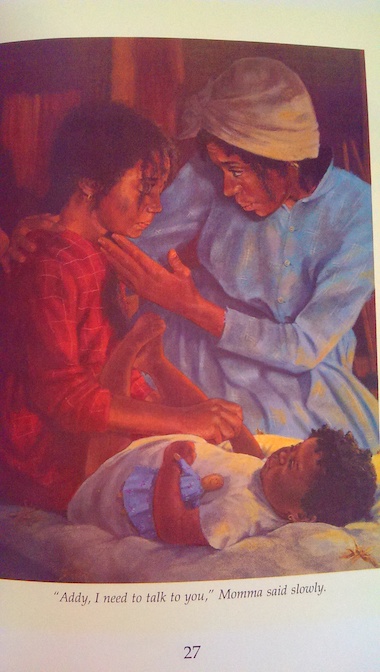

Although Addy and her mother are frightened at the idea of running away, they decide that this is their only chance to escape together. Addy is upset when her mother tells her that they can’t bring her baby sister with them. She is too young for the journey, and if she cries, it might give them away. Instead, they will leave little Esther with their close friends, Auntie Lula and Uncle Solomon Morgan. They plan to find a way to send for them when the war is over.

Although Addy and her mother are frightened at the idea of running away, they decide that this is their only chance to escape together. Addy is upset when her mother tells her that they can’t bring her baby sister with them. She is too young for the journey, and if she cries, it might give them away. Instead, they will leave little Esther with their close friends, Auntie Lula and Uncle Solomon Morgan. They plan to find a way to send for them when the war is over.

The Root Cellar by Janet Lunn, 1981.

The Root Cellar by Janet Lunn, 1981.