The Cartoon Book by James Kemsley, 1990.

I remember buying this book at a Scholastic book fair back in the early 1990s. I didn’t draw a lot of cartoons, but I found the tips in this book to be helpful for drawing in general. The book begins with the useful advice:

“I believe that anyone can draw cartoons. All they need are a few hints to set them on the right track, self-confidence and heaps of PRACTICE, PRACTICE, PRACTICE!”

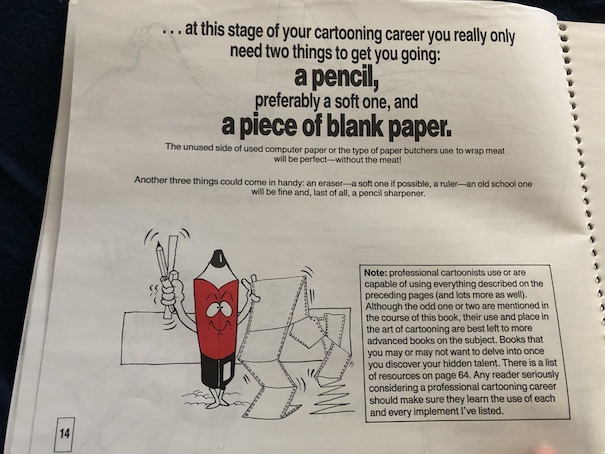

The book aims to make cartooning accessible and unintimidating to even the most basic beginners. There is a section where the author explains about the types of pens, pencils, markers, and other materials that a budding cartoonist can use, which seems overwhelming, but it ends by saying that all you really need is a pencil and a blank piece of paper. Our host is shown as a friendly cartoon pencil throughout the book.

The drawing tips begin with advice for creating character expressions, starting by focusing on the lines and shapes of the eyes. Then, it shows how to add those expressive eyes to heads. What I always liked about this book is that it says the heads can be any size or shape you want them to be. It doesn’t matter if they’re misshapen and lumpy because it’s a cartoon. It’s supposed to be fun and expressive, not perfect, which is very liberating. Even bodies can be different shapes, and they don’t have to be perfect!

Just draw a roundish shape on top of a body, give it expressive eyes, and add an expressive mouth that works with the eyes to show the character’s mood, and there you go!

From there, the book gives brief tips about adding clothes to the body and drawing hands, arms, and legs to show motion. It also briefly shows how to draw animals and animals that are like humans and how to add expressions to inanimate objects and make them characters.

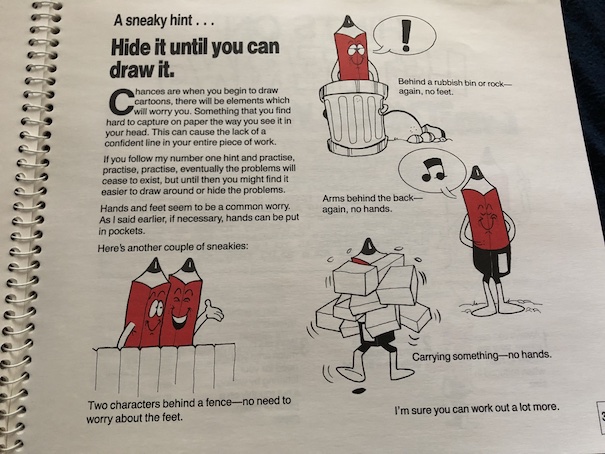

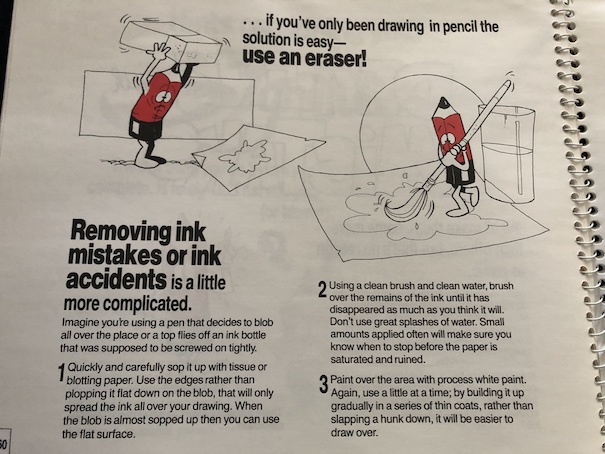

One of the tips that I’ve appreciated is the advice that it’s okay to hide things that you can’t draw well until you’ve learned to draw them better. For example, if you don’t draw hands well, you can just have characters hold their hands behind their backs. There are also tips for fixing mistakes along the way.

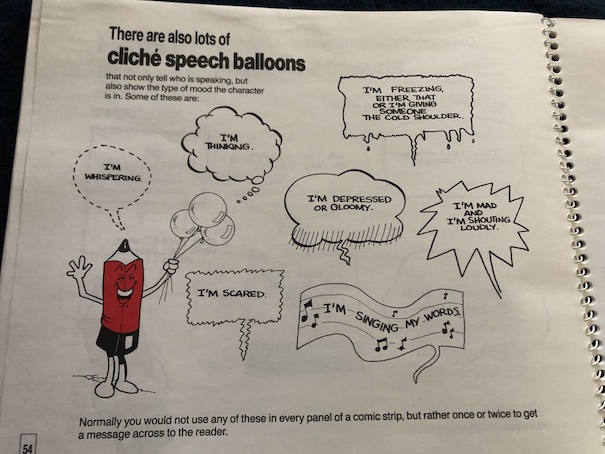

The book also explains how to plan and plot a comic strip. It discusses considering your audience, choosing the types of characters you want to use and giving them personalities, and developing your presentation style with different types of panel borders and speech balloons. It also explains the cliches that cartoonists use, certain common visual signals that cartoonists use to express certain types of speech or events or show movement. The light bulbs over a character’s head when they have an idea is an example of a cartoonist cliche.

The author of this book, James Kemsley, was an Australian cartoonist particularly known for his work on the long-running Ginger Meggs comic strip. I wasn’t familiar with Ginger Meggs when I was a kid because it didn’t appear in newspapers in my area, but I found it interesting to read about when I was looking into the background of this book’s author.