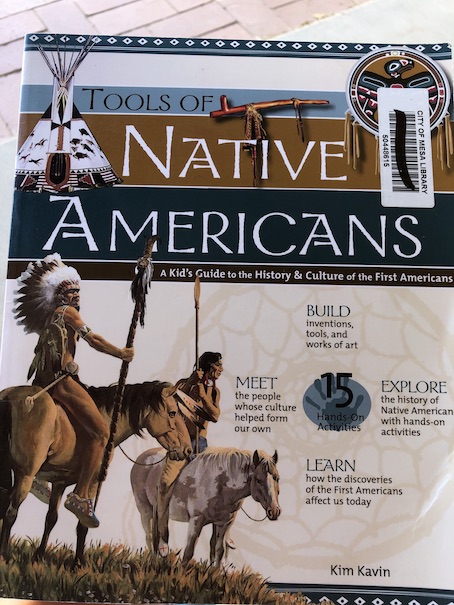

Tools of Native Americans by Kim Kavin, 2006.

This nonfiction book is part of a series recommended for kids ages 9 to 12. It provides insights into the daily lives of Native Americans of the past by explaining their tools and inventions. I was intrigued by the idea immediately because I love books that give insights into history through the lives of ordinary people.

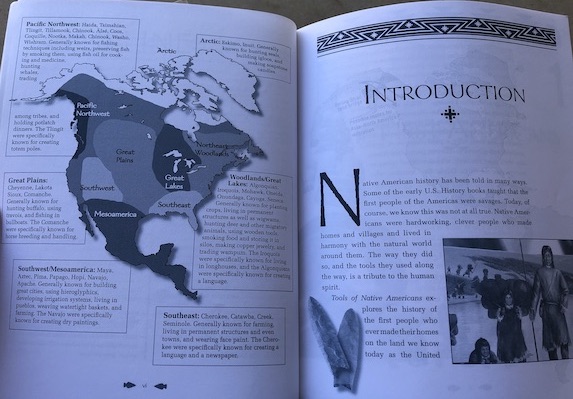

The book is divided into time periods and geographic areas of North America. At the beginning of the book, there is a timeline of important events in the history of North America and Native American culture, beginning c. 20,000 to 8000 BCE, when the ancestors of Native Americans are believed to have migrated to the continent and ending in 2006, the year the book was published. There is also a map showing major geographic regions of North America and the Native American tribes that live there. The chapters of the book are mostly grouped by region, except for the first two, which are about the First Americans and Archaic and Formative Periods.

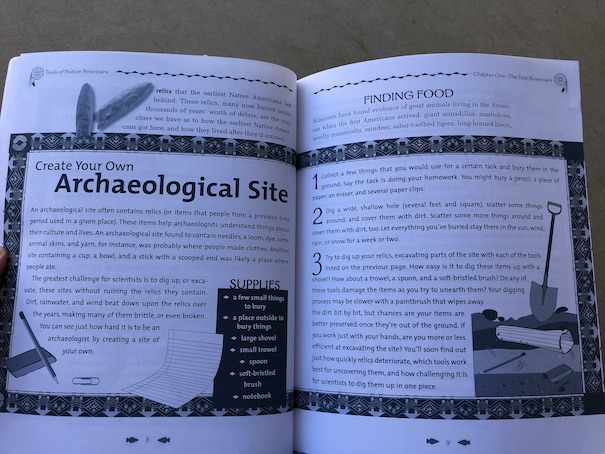

The first chapter, called The First Americans, discusses theories about how the ancestors of Native Americans first arrived on the continent from Asia. The exact circumstances of their arrival are unknown, but there are some possible migration paths that they could have taken. The chapter discusses the Ice Age that existed when this migration took place, how people found food, and Clovis culture, one of the earliest known civilizations in the Americas. One of the activities from this section is about archaeology, which is what we use to learn more about ancient civilizations that did not leave written records, and how to create an archaeological site of your own.

The next chapter is about the Archaic and Formative Periods, which were characterized by climate change as the Ice Age came to an end and many plants and animals that had thrived in the colder climate died off. The changes in the environment cause Native American groups to make changes in their own lifestyles. Rather than relying on herds of large animals for food, they began cultivating crops. They made pottery and developed new cooking techniques. They still hunted, using a device called an atlatl to throw their spears further and with more power. Civilizations like the Maya flourished.

After the second chapter, the other chapters discuss tribes by region:

The Northeast Woodland and Great Lakes Tribes – The Algonquian and Iroquois

This chapter discusses Native American tribes from the East Coast to the Midwest, around the Great Lakes, who primarily lived in woodland areas. The Iroquois and the Algonquian were both collections confederated tribes. There is information about the Algonquian language, which contributed some words to English, including moccasin, succotash, hominy, hickory, and moose. There is also an activity about creating Algonquian style pictographs and petroglyphs.

The Southeast Tribes – The Cherokee, Catawba, Creeks, and Seminoles

The tribes in this chapter lived in and around the Appalachian Mountains. It explains about Sequoyah, who developed a system of writing for the Cherokee language.

The Great Plains Tribes – The Cheyenne, Lakota Sioux, and Comanche

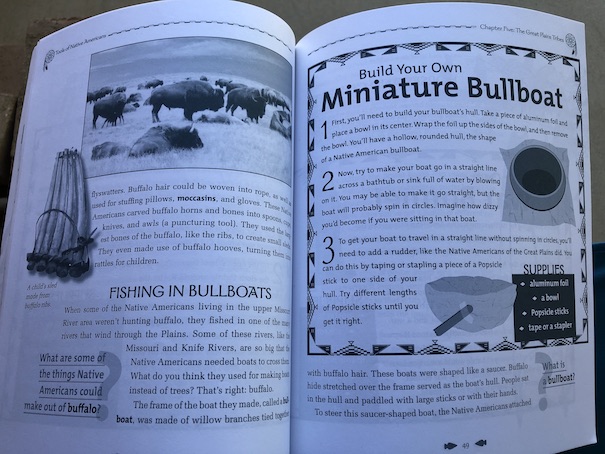

The tribes of the Great Plains were migratory, following herds of buffalo, which were a primary source of food. Because they moved often, everything they owned, from the tepees where they lived to the tools and other objects they used, had to be easily portable. The Comanche were particularly known for being expert horsemen. This chapter also discusses the Lewis and Clark Expedition and Sacagawea, who was part of the Shoshone tribe from the Rocky Mountains. She had been abducted when she was young, and when she joined the Expedition, she was able to guide Lewis and Clark and their men back to the territory she had known when she was a child and to the Pacific Ocean. Activities for this chapter include making a rattle of the kind children used as toys, making a miniature bullboat, and making a war bonnet (using pieces of poster board instead of feathers).

The Southwest and Mesoamerican Tribes – The Hohokam, Mogollon, Anasazi, Maya, Aztec, Hopi, Apache, and Navajo

I know this area because this is where I grew up. Much of it is desert, and the book is correct that there can be sharp differences in temperature between day and night. In modern Southwestern cities, buildings and pavement can hold in heat even at night, but there isn’t much to hold in heat in the open countryside, not even much humidity in the air to hold heat once the sun goes down. There is an abundance of clay in the soil in this region which local tribes used to make pottery and adobe homes.

Among the civilizations discussed in this section are the Hohokam, whose name means “Vanished Ones” (I’ve seen different versions of the translation of that name, but they’re all words to that effect – that they are gone, vanished, disappeared, etc.) because, for unknown reasons, they seem to have suddenly abandoned the area where they had previously lived and farmed for generations. They don’t seem to have died off, at least not all of them. It’s believed that they were the ancestors of the Pima and Tohono O’odham tribes, and the book discusses that a little further on in the chapter. There is a Pima story about a fierce rainstorm and a massive flood that killed many people, but The Hohokam were the ones who built the original irrigation canals for watering their crops. Later, when settlers came from the Eastern United States, they found these abandoned canals, dug them out, and started using them again. The canals are still in use today, and one of the activities in this chapter of the book is about irrigation.

This section of the book also covers the Maya and the Aztecs, who lived in what is now Mexico and Guatemala. There is an activity about creating hieroglyphs, like the kind that the Maya once used.

In the part that describes the Navajo, there are activities for sand painting and Navajo-style jewelry.

The Pacific Northwest Tribes – The Nootkas, Makahs, and Tlingits

Much of this chapter discusses hunting and fishing and the preservation of food. Because food-related work mostly took place during a single season due to the severity of the winters, there were periods of time when the members of the Pacific Northwest Tribes had time for social and artistic pursuits. The book explains the meaning of totem poles, and there is an activity for readers to create their own.

The Arctic Tribes – The Inuit

The lives of the Inuit were shaped by learning to live in a very cold environment. The book explains how they built igloos out of packed snow and ice, but really, igloos were temporary shelters. The houses they lived in long term where made of sod and were partially built underground for insulation. There are activities for building a snow cave called a quinzy (this requires that you live in a place with snow) and for playing a game called Nugluktaq.

The last chapter in the book is called New Immigrants, Manifest Destiny, and the Trail of Tears. It’s about how European settlers arrived in the Americas, the westward expansion of the United States, and the confinement of Native American tribes to reservations.

The book ends with an Appendix with further information about Native American Sites and Museums State by State. There is also a glossary, index, and bibliography.

The Light in the Forest by Conrad Richter, 1953.

The Light in the Forest by Conrad Richter, 1953.