Going to School in 1876 by John J. Loeper, 1984.

Earlier, I covered Going to School in 1776 by the same author. The earlier book was written around the US Bicentennial, when many authors were revisiting patriotic themes. This follow-up book is set a century later than the first, the time of the US Centennial. The author’s earlier book, Going to School in 1776, explains what Colonial American schools were like, and this book explains what schools were like after the US had existed for 100 years, how they had changed in the 100 years since the Colonial era, and what society needed and wanted education to become.

The book starts off with some information about America in 1876. Ulysses S. Grant was President, there were 37 states in the United States, the country was recovering from the Civil War, and there was a huge exhibition in Philadelphia to celebrate the Centennial. The Centennial Exhibition included exhibits by American industries, showing off new inventions, such as steam engines and sewing machines, and there were exhibits contributed by other countries. Now that railroads and telephones were linking different parts of the country, the general outlook was one of optimism and a fascination with progress.

However, American society was still largely rural. Since newspapers only had limited ranges of circulation, there was no mass media that could reach everyone, the spread of information wasn’t entirely reliable, and news often depended on word of mouth. Education also varied widely throughout the country. The concept of public schools, with taxes paying for anyone who wanted to attend, was controversial. The book says that some people resented the idea of “paying for the schooling of rich and poor alike,” although it doesn’t go into detail about arguments surrounding the issue. Although, in the 21st century, there are public schools across the nation, and the idea of public education for children from elementary school to high school is pretty common, there are still people who quarrel with the concept, with assertions like “Why do I have to pay for people who could be paying for themselves?” and “I paid for myself and my children, so why should I have to pay for anyone else?” I think that studying the types of schools that the US had in the past partially answers these questions.

The beginning chapter of this book references the earlier book and types of Colonial schools, like blab schools and dame schools, which no longer existed by 1876. By 1876, it was more common for children to be educated in formal schools and trained teachers, although the quality of schools varied by region, and not all children attended. There were schoolhouses even in rural areas, but not all schools were well-equipped, and some wouldn’t accept all students. Many states were passing laws about educational requirements, but children were still heavily used in labor in mines and mills. To explain the nature of education in the late 19th century, the book explains that it will examine the daily lives of children in that period to show what their living circumstances and schooling were like.

(Note: After a fashion, something like dame schools reemerged during the Coronavirus Pandemic of the early 2020s, when public schools were closed or converted to online forms. During that time, many people turned to homeschooling in various styles, and there were some homeschooling groups with parents sharing teaching and supervising responsibilities for their children and a small group of other children in their homes, which is sort of what the earlier dame schools were like. However, this book was written written long before that happened, and the 21st century version was more an aberration, a departure from the norm for the time period, by people reacting to unusual circumstances.)

From that point onward, each chapter of the book focuses on a different aspect of children’s lives and education in 1876. To illustrate each of these concepts, rather than just stating the dry facts or statistics about 19th century children, the author tells short stories about individual children as examples. Below, I’ve explained what chapters and sections of the book are like and what information they cover, although I changed some of the heading names of the sections to highlight the educational topics covered rather than the stories about children that were given as examples. The titles of some of these sections in the book, which describe the stories rather than the information, wouldn’t make sense without retelling the story, but this book is available to read online for those who would like to explore this topic further and read the stories for themselves.

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive.

Chapters in the Book:

Being a Child in 1876

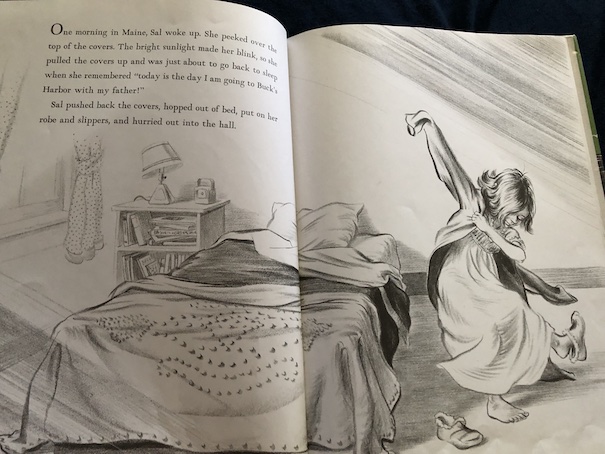

To give readers an idea about the varying circumstances of 19th century children, the author describes the daily lives of six children, who each live in a different part of the US or in a US territory. Each of these descriptions are told in the form of a short story. The author makes the point that the level of education children of this era receive is based not just on geographical location but also social class, and there were major gaps between the education of poor children and wealthy children. The stories he tells about different children around the country illustrate the point. I was pleased that he not only described the lives of children of various social classes and regions, but he also included a Native American girl in this chapter. The Native American girl example is one of the better and more hopeful examples of Native American education for the period, not one of the traumatic ones of the Native American boarding schools of the 1800s.

(Black people are covered in other chapters as the next-largest racial group next to white people at this time and because the Civil War drastically changed their educational prospects, but I have more to say about this later and in my reaction section at the end. Where race/ethnicity is not stated, assume that the people described are white because that’s the majority race/ethnicity and the assumed general default for this time and location. Asian people or Hispanic people are not mentioned at all in this book.)

Farm Child in Massachusetts

Jim Porter is a ten-year-old boy in a village in Massachusetts. His daily routine involves chores on his family’s farm and attending the local schoolhouse. There were laws in Massachusetts mandating that children attend school from the ages of 8 to 14 for at least 12 weeks a year (that’s about 3 months a year), but these laws were rarely enforced. If a child hated school or couldn’t get along with a teacher, the child might simply quit going to school, and very likely, nobody would do anything about it. Children who stayed in school did so either because they wanted to continue going or because their own parents insisted that they continue going because few other people would care if they did or not. Children’s parents would pay tuition fees to the local school committee, just a few cents a day for each day the child attended school (although even a penny went much farther in the 19th century).

Child Coal Miner

Ten-year-old Patrick Doherty lives in Pennsylvania and works in a coal mine. He works every day, except Sunday, and he is only paid a few cents a day for his work. There are some laws about child labor in his time, but not many, and even those that exist have many loopholes. Many parents of this time are poor and need their children to work and earn more money for the family. For them, it’s a necessity, not a preference. Employers liked child labor because they didn’t have to pay kids much. Some people even said they though it was better for children to work and called laws limiting child labor “soft” and “silly.” The book doesn’t shy away from describing Patrick’s harsh and unsafe working conditions, describing children’s “raw and bleeding” little hands and bodies covered in coal dust, the bad and dusty air in the mines, and cave-ins. The only school in Patrick’s town is the local Sunday school, which teaches a little reading and religious education. The town was built by the coal company. The coal company owns all the businesses and buildings in town, and the coal company says that the children don’t need a school because they’ll learn everything they need to know by working in the mines.

Farm Child in Iowa

Jim Wright is a twelve-year old boy in Iowa. His family used to live in Maryland, but his father moved the family west. They live in a cabin near a lake and grow wheat, oats, and barley on their farm. Jim works on his family’s farm, and he and his sister attend the local schoolhouse for a few weeks each winter, between the planting and harvesting seasons. Iowa has had tax-supported public schools since it became a state in 1846, so individual students do not need to pay when they attend. However, there are no laws requiring children to go to school, and families still prioritize the work that children do at home and on the farm. Jim’s father thinks that a few weeks of school a year are all his children need.

Immigrant Child in New York City

Eight-year-old Tony Wasic is from an immigrant family, and his family lives in a crowded tenement building in New York City. Tenements are a cheap form of apartment where many poor people and immigrants live, and they often have many people crowded into very few rooms, with poor conditions and few amenities. An entire building of people might have only one outdoor toilet and only one water tap outside the building, so they would have to haul buckets of water inside for cooking or baths in wooden tubs. Because of the crowded conditions and poor sanitation, they were often breeding grounds for disease, and they were also often fire risks. Tenement slums could be found in major cities, like New York City and Chicago. New York City established a public education system in 1867, so in spite of their poverty, Tony and his brothers can go to school without paying fees to attend. After school, he sells newspapers to help raise money for his family. His ambition in life is to own a grocery store.

Native American Child in Oklahoma

Anna Crowfoot is a 12-year-old Native American girl. She is part of the Cherokee tribe, and she lives in the part of Oklahoma known as Indian Territory. She knows that her people were forcibly moved from their ancestral lands into this territory by government troops during the 1830s. Not many people during this time are concerned about educating Native American children (the book uses the term “Indian” instead of Native American), at least not in any formal way, but the ones who do offer formal schools for Native Americans see education as a way to “civilize” them, Christianize them, and change their lifestyles from the “savage ways” of Native Americans to that of mainstream, predominantly white/European based US culture (the quotes around the words in this sentence also appeared around those words in the book – those ideas are ones expressed by people of the time and do not come from the author, and the author wants readers to know). In short, the people running schools for Native Americans have no interest in Native American culture and would rather see them give up their culture. Whatever the Native American children learn about their tribe’s culture and history comes from their families at home.

Anna attends a girls-only school, where the girls are taught skills that farm wives would find useful, such as how to cook, how to sew, and how to make medicines from herbs. (Herbal medicines are popularly thought to be more Native American than a white person’s thing, but in the days when most people lived on farms or in rural areas and weren’t very near doctors, everybody had to know how to make a few basic remedies for common ailments. White people did have a tradition of herbal medicines from Europe, but one of the issues with that was that white people were more familiar with plants from Europe than plants native to the Americas. The book doesn’t explain this, but European colonists brought some of the plants that they commonly relied on from Europe, and apart from that, they had to learn how Native Americans used the local plants.) The Native American boys learn how to be farmers at their school. (Exactly how this kind of education differed from their traditional Native American lifestyles depends somewhat on the tribe, but basically, one of the goals was to make Native American society into permanent agrarian settlements, specifically on land nobody else really wanted, rather than nomadic or semi-nomadic, which had been the previous way of life for some of them. They also learned to grow different types of plants than the ones that their society would have traditionally cultivated, more in line with the European-based crops favored by white people.)

Anna is described as enjoying her school and lessons in “some of the white man’s ways” (I added those quotes, just quoting from the book), but she also values the ways of her tribe. (This is one of the more benign descriptions I’ve heard of what “Indian schools” could be like. Real life stories could be much worse, and that’s part of the reason why Native Americans would try to avoid sending their children, if they could.) Her ambition in life is to become a teacher herself and to start a school for Cherokee children that will also teach Cherokee traditions.

Middle Class or Upper Class in Indiana

Nancy Feather is the most fortunate of the children described in this chapter. She is an eleven-year-old girl whose father owns a hardware store in Indiana. They are a “middle-class” family. There are other people who are more wealthy than they are, but the Feathers have a very comfortable lifestyle, with money for some luxury items, including some that modern middle class families would be unable to afford. The Feather family employs a cook and a gardener and even has a summer house at a lake. Mr. Feather is a respected businessman in his community, and like others of their social class, the family is concerned with maintaining a good social image. The Feathers make sure that their children are always clean and neatly dressed in public. The children also learn etiquette, so they make a good impression on people they meet. They value education and culture, and they can afford the best education their community can offer and lessons that are not solely focused on employment skills. Nancy attends Miss Dwight’s Academy, which emphasizes that they teach music, art, classical literature, and French.

How Children Dress in 1876

This chapter has short little stories about a different set of children from the ones described in the previous chapter. This set of stories focuses on what children wore in 1876. Social class and money are factors in the clothes they wore, but the author also brings in other issues, such as health theories and cultural habits. This chapter seems to further elaborate on the range of lifestyles and daily life activities of children and also helps readers to picture the people they’re reading about.

Boys in Wool Suits

Nine-year-old Fred Hart gets a new suit to wear to the Centennial parade on the Fourth of July in his town. Fred doesn’t want to wear the suit because it’s really too heavy for the summer weather, but his mother insists that he wear it because she doesn’t want him to “catch a chill.” The book explains that there were no vaccines to prevent disease at this time, so parents and doctors recommended other precautions, including wearing heavy clothing year-round to avoid “chills.” (This comes from the misconception that colds are caused by literally being cold instead of by viruses.) Dr. Gustav Jaeger, a German doctor, spread a popular theory that wool was the healthiest clothing, telling everyone that plant fibers like linen and cotton wouldn’t adequately block air from touching or moving across the skin. He also believed that clothes should fit tightly to be less breathable. Not everyone agreed with his advice or followed it, but it was a popular theory that governed the way some people dressed.

Poor Children in Flour Sack Clothes

On the other hand, Anna Jenkins is a poor child in a mill town, and her dress is made from an old flour sack because her family can’t afford anything better. They have to improvise clothing from whatever they can find or have available. She dreams of one day owning a pretty silk dress.

Sailor Suits

Ten-year-old William Smith wears a nice sailor suit to church. He wears a wooden whistle around his neck as an accessory, but his mother tells him that he shouldn’t be blowing it on Sunday.

Fancy Dresses and Accessories for Little Girls

Lucy Preston wears a pink dress decorated with rosettes and a blue ribbon sash with a bonnet and white gloves when she visits her grandmother. Her grandmother believes that proper young ladies should wear pretty and fashionable clothes and “behave in a proper manner.” Lucy’s outfit isn’t particularly comfortable, but her grandmother also believes that sacrifice is necessary for the sake of style. This section of the book notes that children’s fashions of the era are based on adult fashions rather than being designed specifically for children.

Different Outfits for Different Purposes of Young Ladies

Twelve-year-old Mary Trent gets her first corset and a dress with a bustle, fashionable touches that mark her as becoming a young lady rather than a mere girl. She writes a letter to a younger cousin about it. She is excited about her new clothes, although she admits that they are difficult to wear. She finds it harder to breathe in the corset, and she admits that her new button boots are difficult to put on, but she thinks that it’s important to wear the right kind of clothes, and she’s looking forward to wearing them when she visits her aunt.

Her father is irritated with her for being too obsessed with clothes, but Mary says that he doesn’t understand because he is a man. Men of their time wear suits for every occasion. A couple of suits for work and church are about all they need. On the other hand, fashionable women are expected to have different outfits for different purposes, including walking dresses, riding dresses, morning dresses (simpler, more informal garments to wear first thing in the morning for breakfast and other activities at home, before dressing to go out for the day – unlike other dresses of the era, they were more loose and could be worn without a corset – sort of like the 19th century version of feminine lounge wear, although the term “morning dress” later came to indicate a more formal type of outfit in the 20th century), and church dresses. Basically, each of these styles of dresses have features that make it easier to do certain activities, rather than the women having a single outfit that was comfortable and easy to wear for a variety of activities. (See the YouTube video Why Did Victorian Women Change Their Clothing 5 times a Day? for more detailed explanations and examples of different types of Victorian era women’s outfits.) With more variety in styles and additional requirements for different types of outfits, women have more decisions to make in the clothes they choose, so there’s more for them to consider.

The Schools of 1876

Unlike the previous two chapters, this chapter focuses on school systems, school districts, and individual schools rather than describing individual students who attend them. It isn’t clear whether the schools the book describes are/were real schools or if, like the children described earlier, they are intended as just general examples of types of schools and school conditions that existed in 1876. I tried looking them up, and I couldn’t find information about them, so they might be fictionalized examples, but they do work as examples to illustrate school types.

One-Room Country Schoolhouse

The Wexbury District School is a one-room schoolhouse one mile outside of town. The book explains that it was common in the 19th century for public schools to be called “district schools” because they served students in a particular area or district. The local school committee (sometimes called school directors or school board, depending on the area) governs the school, pays the teacher, and maintains the school building, using money collected from taxes. However, they don’t pay the teacher much, and the teacher is also responsible for cleaning the school. Public schools of this type could vary in size and the number of teachers, depending on the needs of the local district, but Wexbury District School is just a small, one-room schoolhouse, so it only has one teacher for all the students, regardless of age or grade level. There just aren’t enough students to separate them out into different rooms with different teachers. The Wexbury District School is a kind of dingy gray little building with a couple of outhouses behind it, and truancy is high because the area has weak laws about school attendance. Most days, less than half of the students in this district attend school. Part of that is due to the poor condition of the school. The book quotes an unnamed Connecticut official’s observation that schools are often less comfortable than prisons. One thing the Wexbury District School has that is considered a new innovation is a blackboard. The book says that blackboards were a new development for 19th century schools, and not everyone thought that they would be a lasting trend.

Small Local School Districts/District Schools

The book explains that school districts in southern and western states are named for the town or the area they serve, and some of them have really colorful names. The example of this is Fly Hollow School in West Virginia. Fly Hollow is a very rural area, and most people live on scattered farms, although many of the local families are related to each other. However, the schoolhouse in 1876 is new because West Virginia only established its public school system in 1872. It’s a one-room schoolhouse with one teacher and ten students, most of whom are the teacher’s younger cousins or nephews. The teacher decides when students are ready to pass to the next grade, and the teacher at this school refuses to pass students until they’re really ready, even though they are relatives of hers. Her standards are strict, and she holds to them.

Pioneer Sod Buildings

By contrast, the Logan County public school in Nebraska, is run out of the teacher’s house, which is only a small sod building. Sod houses, made of bricks of sod, are common for pioneers in Nebraska because wood is rare on the prairies. They only have dirt floors, and the conditions are rough and uncomfortable. However, charmingly, plants will grow in the sod bricks, so flowers will grow out of them and bloom in the spring. This particular school and teacher has only six students, and they are supported with state funds.

Small Private Schools

The Millville Academy is a private school for boys. When the schoolmaster opens the school, he advertises the opening in the newspaper, describing what subjects will be taught at the school and what the school fees are. The schoolmaster will be running the school out of his own home, and he will teach science and classical learning. As part of the school’s services, the students will also be provided with a midday meal. Private schools like this were often found in larger towns, and their students were from upper class families. Along with the academic subjects, they would teach etiquette and proper behavior. The midday meal this school provides is also a lesson in how to behave at a dinner table. The schoolmaster uses some harsh punishments on his students, including locking them in a closet. (Abusive by modern standards.) His lessons are rigorous because he wants to prepare the students to go on to college. The schoolmaster’s credentials for teaching are that he is a graduate of Yale.

Upper-Class Academies and Seminaries

While upper class boys’ schools were called “academies”, schools for upper class girls were called “seminaries.” The headmistress of a female seminary was often an educated woman who was either the wife or daughter of a minister. Sometimes, they came from Europe to teach because upper class American families wanted their daughters to learn another language, such as French. Typical subjects at a female seminary might include spelling, writing, music, drawing, sewing, and embroidery.

Segregated Schools in the South

My summary of this part is going to be longer because I think this requires more explanation. Prior to the Civil War, there was no education for black people in the southern states because black people were slaves. (The book doesn’t explain this, but there were actually laws forbidding teaching black people to read. Occasionally, some sympathetic white person would do so anyway in defiance of the laws, or black people themselves would find a way to learn and teach others, but they were rare exceptions.) After the Civil War, the southern states developed a public education system that provided for the education of both black children and white children, but it was a dual system with separate schools for children of different races. Even with separation between the black and white people, the subject of educating black people at all was controversial in the south, with some people calling it a waste of money.

(Think of it this way: If some people generally didn’t like the relatively new idea of public education because it meant paying for other people’s children to attend school through their tax money, imagine how those people might react when they find out that this is going to include paying not just for the children of friends and neighbors they like or might potentially do business with to go to school but also a group of people they specifically hate and resent. I’m not saying that this is well-reasoned, ethically right, or a healthy mindset, just that this is the sort of thing that might be going through people’s minds at the time. The book doesn’t explicitly explain this, although it does indicate that this is how some people of the time feel without going into specifics. Educating people in general might not objectively be a “waste of money”, but what I’d like to point out is that these people are not being objective but very personal about it. They, personally, don’t want to spend their money, and they especially don’t want to spend it on people they personally don’t like or even want to associate with in their daily lives. We’re about to see what they and their children do in response because the book does explain that.)

The example the book describes of a school for black children in the South is Goose Creek School in South Carolina. It’s a small school with only two rooms, and there is only one teacher. The teacher is from the American Missionary Society, an abolitionist organization founded prior to the Civil War which had an interest in providing education for black people after slavery was abolished. The children at Goose Creek School learn basic subjects, such as reading and writing, mathematics, hygiene, and farm skills. A black boy named Jason attends this school, and he gets teasing and physical abuse from white children and even some other black children because of it. They accuse him of being “uppity” and thinking that he’s “somebody special” for going to school. However, he still wants to go to school, and his mother and teacher encourage him to continue his education because this is an opportunity that people like him never had before.

Because this book only focuses on conditions during one year, 1876, it doesn’t explain the futures of any of the children or schools described so far. However, readers with some historical background will know that this segregated system of education continues into the mid-20th century, until the Civil Rights Movement and school desegregation. Having seen footage of people reacting to school desegregation in the mid-20th century, the behavior of opponents to education for black people described in this 19th century is very similar.

A question readers might ask at this point is, was school segregation limited to only the South? Because of the history of slavery in the South and its previous laws against education for slaves, the idea of 19th century southerners being opposed to their children being educated alongside black people or even black people being educated at all makes logical sense just as a progression of events and in keeping with the long-term attitudes of the people involved in the public decision-making. What I’m saying is that educational segregation is not great but not surprising, given the context. People might expect that attitude in former slave states, and their official dual school systems and Jim Crow segregation laws made the South the focus of desegregation, the area of the country always most associated with the idea of segregation. It certainly isn’t an undeserved reputation.

However, others might point out that even northern states had some slavery, and they still had their share of racism, and that’s also a fair observation. So far, in this book, there has been no mention of racism with relation to any schools or school systems outside of the South, so readers might wonder what was happening in Northern schools with relation to race during the 19th century. I have things to say about that in my reaction section below because I think this is a good topic to cover that’s missing from this book.

Public School in a Large City

At this point in history, large cities already have established school systems, and public education is just accepted as a normal part of life. Because there are many schools in a large city, they are often given numbers instead of names, such as “P.S. 84.” The “P.S.” stands for “public school.” Class sizes are large, about 50 to 60 students in a class. One of the challenges they face is helping students from immigrant families, who are still learning English and adjusting to life in a new country. School superintendents are often political appointments, so there are some accusations that the schools are too political.

Church Schools

Some of the very first schools in the United States were church schools, and there have been church schools here ever since. They were very common during the 19th century. Religious groups of all types had schools of their own, and they taught religious classes alongside more basic subjects, such as reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, and history. Although church schools were familiar features of American education, some people criticized them for being too insular, preventing children from mixing with the broader population, keeping them from being exposed to people with different religions, and confining them to their own ethnic groups.

Kindergarten

There weren’t many kindergartens in the US in 1876. The very first public kindergarten in the US was founded in 1873 in St. Louis. Kindergartens were the concept of a German educator named Friedrich Froebel and were meant to help young children become prepared for regular school. At kindergartens, children would learn to play with other children and become adjusted to the concept of leaving their mothers and attending school. Some people at the time criticized the concept of kindergarten because they thought that it was silly and that young children weren’t developed enough to begin learning much.

The Teachers of 1876

Teacher Examinations

Job requirements for teachers in the 19th century were far less strict than in the 21st century. Not all teachers even had a high school education, and when they did, high school was often the highest level of education they had. They were typically graduates of whatever local school system they hoped to teach in. To gain teaching status, they had to pass whatever examination was established by the local school superintendent to establish that potential teachers had sufficient knowledge of the subjects they planned to teach.

Normal Schools

In 1834, American Charles Brooks had an interesting conversation about education with a German man while they were traveling together by ship. The German man described how, in Germany, teachers were given specialized training in order to become teachers. Brooks thought the concept was fascinating, and when he returned to the United States, he promoted the idea of specialized teaching colleges called “normal schools,” which would not only give potential teachers mastery of the subjects they would teach but also instruct them on the theories of education and teaching techniques. By 1876, normal schools were becoming common features of American education, and trained teachers became in demand for teaching jobs. (The book doesn’t mention this, but some state universities, including the one I attended, originally started as normal schools before gradually expanding as larger colleges, and eventually, universities.)

Godey’s Lady’s Book

Godey’s Lady’s Book was a popular magazine for American women in the 19th century, and it influenced American life by influencing American women and mothers. (I’ve mentioned it before as one of the magazines that promoted the concept of Halloween as a children’s holiday, around the same time as this book is set, with ideas for mothers to help set up children’s parties, offering suggestions for decorations, costumes, and games. This book doesn’t mention Halloween, but I like to tie into earlier subjects I’ve covered.) Godey’s Lady’s Book promoted the idea that there should be more female teachers in American schools. There were relatively few respectable professions for women during the 19th century, and teaching was one of the more genteel professions, making it an attractive job for unmarried women. The magazine pointed out that, since married women of the time were expected to give up whatever job they had to care for a household and raise children of her own, they wouldn’t need as large a salary as a man would, if he had a family to support. Because women would work for a cheaper salary and had a nurturing, motherly image, teaching gradually came to be thought of as primarily a women’s profession in the United States, although some people questioned whether female teachers had the same academic rigor of male teachers.

Teaching and Marriage

While teaching was becoming a popular profession for women, it was only for unmarried women. Few school systems would hire married teachers because they assumed married women wouldn’t have much time to teach with their own households and families to manage. Unmarried teachers often lived with their parents or other family members or boarded with other families who lived near their schools. There were opportunities for professional teachers to continue studying educational techniques and to form groups with fellow teachers to share information.

The Lessons of 1876

A Day in a Country School

This chapter covers what students often studied in American schools, and it starts with a section about a typical day in a country school. All of the students would typically walk to school, no matter what the weather was like, and many of them had to walk long distances. (This aspect of historical education in the US is what started the old joke about elderly people claiming that they had to “walk to school in the snow, uphill … both ways!”) Classrooms might have an American flag, but the students wouldn’t say the Pledge of Allegiance because it hadn’t been established yet, and they didn’t sing the national anthem because no song had been chosen as the national anthem yet in 1876. Instead, students would start the day with a reading lesson from McGuffey’s Ecletic Readers, a popular set of books with reading lessons and selections of stories and poems. McGuffey’s Eclectic Readers also helped to transmit important pieces of American history and culture in their readings.

The students would then study arithmetic, take a recess break, and then have a writing lesson. When it was time for lunch, the students would eat in the classroom. They would bring their own food or sometimes eat soup the teacher would make on the classroom stove. Then, they would study history and geography, and they might have a spelling bee.

Copybooks

Although many schools use slates for writing practice, students would write their best and most important pieces in copybooks.

Lessons in Discipline

As an example of a kind of inspirational lesson a teacher might use to correct a student’s discipline problems, the book tells the story of a student who is caught in a lie by his teacher. The teacher assigns him to read the story about George Washington and the cherry tree from A History of the Life of General George Washington by Mason Weems. The book notes that many of the incidents of George Washington’s life were fictitious, the book was very popular in the 19th century and used in many classrooms. Weems’s book was the origin of many popular myths about George Washington’s life, and although this book doesn’t mention it, even though Weem’s book was popular, it did receive criticism even during the 19th century for its inaccuracies and fantasies.

Arithmetic

In 1876, it was common for schools to teach students to do mental arithmetic instead of having them write everything down. Mathematics lessons covered the basic operations of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division, plus fractions, decimals, and units of measurement.

Report Cards

Report cards on students’ learning progress and behavior at school were very common and often required of teachers. Teachers might require parents to sign a child’s report card to prove they had seen it, and parents might punish children who misbehaved at school and didn’t do their schoolwork.

School Life in 1876

School Rules

Large schools might post a list of school rules in the hallway along with the punishments for breaking them. The book presents an example of what might happen to students who misbehave.

Immigrants in School

The book offers an example of what school was like for young immigrants. Schools helped immigrants to learn American history and heritage as well as English, helping them to assimilate to American culture.

School Discipline

The book has an account of how harsh and intimidating school punishments could be. It also describes how some misbehaving children escaped punishment by stirring up other students and watching as they got punished while they put on an innocent act. Sometimes, teachers seemed to take an almost sadistic pleasure in dealing out punishment.

Recess and Games

The book tells an anecdote about some boys who were so busy playing sports at recess that they came back to class very late. Their teacher banned the boys from going to recess for the next five days.

The Discipline of 1876

New Teacher

The book describes some boys talking about how they aren’t afraid of their new teacher, but 19th century teachers were tough, strict, and not afraid of administering even physical punishments. The next small section describes the punishment given to a pair of misbehaving boys.

Advice from a Magazine

A girl reads advice on the discipline of children from a magazine. It was becoming more common to allow children some degree of freedom, but obedience to parents was still expected.

Conditions of Poor Children

Life was hard for poor children, and they often faced cruelty and neglect, including harsh physical punishments from employers. Because conditions were getting so bad, citizens in New York formed the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.

Reform Schools

Children who actually committed crimes or were completely uncontrollable might be sent to reform schools, which were also called industrial schools. There were reform schools for girls as well as boys. The children would live at the school, and parents typically paid for the children to be there. Aside from school subjects, children in reform schools also had to perform long hours of work.

Orphans

“Orphans” not only included children whose parents were dead but also children whose parents were simply unable to care for them, perhaps because they were sick, in jail, had no money, or were divorced but neither parent was able to look after the children. Orphanages would care for children until they were old enough to work, and then, they were often hired out as domestic servants.

After School in 1876

Circuses

Traveling circuses were a major source of exciting entertainment, and their arrival in town was often like a holiday.

Children’s Books

Popular books for children in 1876 included the Rollo books by Jacob Abbott and Hans Brinker or the Silver Skates by Mary Mapes Dodge. Children also enjoyed books that we might think of as adult classics now, like The Last of the Mohicans by James Fenimore Cooper. There were also magazines for children, such as St. Nicholas Magazine. Sometimes, children would also read sensationalist adventure stories in “dime novels,” although parents might consider this form of literature “trashy.” Parents and relatives might give children books or magazine subscriptions they approved of as presents for birthdays and Christmas.

Baseball

Baseball evolved from several older games involving balls and bats. By 1876, there were organized, professional teams and a national league.

Football and Lawn Games

Football wasn’t as popular in America as baseball in the 19th century. However, there were a few college teams that played against each other. Popular lawn games in the 19th century were croquet and lawn tennis.

Swimming

It was popular for children to swim in local ponds. Boys would often swim naked in ponds, although swimsuits were required for public beaches.

Playing in the City

Children living in big cities could play in parks, in vacant lots, or just out in the street. Girls often liked to play hopscotch, and boys would play tag. Poor children didn’t have much time to play because they often had to work. However, parks offered green spaces where children could explore among the trees, watch birds and squirrels, or play with toy sail boats on a lake.

My Reaction

I included some of my opinions and some additional historical information within the review itself, but there are a few more points I’d like to make. I looked up this book because I found the first one, Going to School in 1776, fascinating, and I wanted to see what this book would say about changing education in the US from the 18th century to the 19th century. What I appreciated about both books was that they connected the types of schools children attended and the types of education they received to the actual, daily lives of children at the time and the types of lives that they were likely to lead as adults. No matter the era, I think that the type of education a child receives reflects both the realities of their current life and the kind of life that adults caring for them think that they are likely to lead in the future. In the context of 19th century children’s lives, their levels of education and the attitudes of their families toward education make sense.

However, we know that not only did schools not stay the same between the 18th and 19th centuries, the conditions of education in the 20th and 21st centuries are different yet from either of those. Even my own childhood school experiences from the late 20th century aren’t quite like what kids have been experiencing in the early 21st century, and that’s just a difference of about 30 years. Part of that is due to changing technologies since my childhood, but also, it’s about changing expectations about the lives that children will eventually lead. Not only are there almost no jobs in 21st century America that will hire anybody who doesn’t have at least a high school education, there are relatively few jobs that pay a living wage that don’t require either a college education or some form of professional training or certification beyond high school. The schools children attend in the 21st century have that in mind.

One of the controversies about modern education is the way that schools address topics like racial issues. Some schools definitely handle topics like this more effectively than others, but ignoring the issues is not an option for 21st century schools because modern people mix more with people of different cultures and racial backgrounds. Kids have to grow up understanding more about other people’s backgrounds and how to interact with other people than, say, a kid who lived on a 19th century farm and spent most of his time with his own family and occasionally people from nearby farms or the nearest small town. If you rarely see other people in general and almost never interact with anyone whose background is different from yours, then learning to understand other groups of people and how to speak to and about them politely would not be a high priority. (I talked about this when I was reviewing Little House in the Big Woods.) However, that is not even remotely the type of life people in the 21st century have, unless they’re deliberately trying to isolate themselves. Anybody who is reading this review, no matter who they are or where they are, has Internet access and, by extension, the ability to speak to people from all over the world. People of the 19th century were pretty excited by the concept of communicating with people over distances by telephone, but the idea of communicating with large numbers of people around the world would have been incredible to them. The school systems of the 19th century would never be able to prepare students for the kinds of lives people live in the 21st century, which is why we have the school systems we have today instead of the ones we used to have.

School Segregation in the North

In the section about segregated schools in the southern states, I pointed out that the book doesn’t address whether or not schools were segregated in the northern states or anywhere else in the country. I’m going to discuss that here and also point out some of the reasons why segregation and discrimination in the South stood out more than other places.

There was also segregation in northern states, but just as schools and school systems varied, racial laws and conditions also varied by location. In the United States, schools have always been regionally governed, and there can be considerable variation on the way schools are run from region to region, depending on who lives there and what their priorities are. There were both official laws segregating races in various public settings in northern states and unofficial customs and economic factors that effectively created segregated circumstances that weren’t covered by laws. Because I think this is an important and complicated issue that the book doesn’t cover, I want to give a brief run-down of these factors.

As some people have observed, historians tend to focus more on the unofficial factors of racial segregation when it comes to the northern states instead of discussing the formal laws, and I think that’s partly because the southern states had a much more visible system of segregation. Given the South’s history of institutionalized slavery and their official “separate but equal” school systems prior to the Civil Rights Movement, everyone has watched the South’s racial issues much more closely since the Civil War than they have other parts of the country. The South’s stance on segregation was a very visible and deliberately enforced part of public policy during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Of course, none of that means that the North didn’t have its problems and its own bad behavior and segregation laws. It was more that what it looked like in the northern states was different from what it looked like in the South because of the South’s position in the Civil War and because racial demographics were different in the northern states, compared to the southern states.

Prior to the Civil War, even in northern areas where black people were allowed to attend schools, there was an official policy of segregation. Soon after the end of the Civil War, official legislation “outlawed school segregation in all northern states except Indiana.” However, just as formal school attendance laws were often ignored or rarely enforced when they didn’t suit the people involved, laws forbidding school segregation in the North were also ignored whenever it suited the white people involved. Schools were always managed at the local level, and if the local white people didn’t want black people attending their school, they would find ways to stop them, whether officially or unofficially. Black people had little legal recourse in places where they were outnumbered, wider public opinion was against them, and they couldn’t find or afford lawyers to help them argue their case.

Another factor to consider is that racism tended to be stronger in areas with higher populations of black people, and this applied to both the North and the South. The South had much higher numbers of black people than any area of the North during the 1870s, the focus period of this book, and within the northern states, some areas had higher populations of black people than others. In fact, some areas of the North had few or none. That makes a major difference in the priorities and concerns of the people who were living in these areas.

The 1870 United States Census is telling because it was the first U.S. census to gather detailed information about black people. You can read the full census online, and when you start examining the aggregate population information with race and study the numbers of total population, population of white people, and population of “colored” people, you realize that black people, while still a minority in 1870, were a very large minority in southern states. They were definitely a minority politically and socially, but in some areas of the South, their numbers actually rivaled those of white people. For example, black people made up 46% of the aggregate population in Georgia, and in Mississippi, they were actually the majority at 53% of the aggregate population. In South Carolina, black people were 58% of the aggregate population. By contrast, black people made up only about 1.8% of the aggregate population of Connecticut, 0.26% of the aggregate population of Maine, about 1.2% of the aggregate population of New York, and about 2.5% of the aggregate population of Ohio. The racial demographics were radically different between the different regions of the country, and that changed the ways the racial groups interacted and how the laws in different regions were made. Where there were more black people, there seemed to be more concern about white and black people mixing in public facilities and more rules to prevent it. It also changed how visible the treatment of people of different races could be. One of the lessons I take from this is that making laws that oppress a particular part of the population becomes much more obvious if the part of the population being targeted is about 40% or more of the total population than if it’s only about 2% or less. I think this is a major factor in how visible Southern segregation was and how Northern segregation was easier to overlook.

Because the South had a higher population of black people, they could justify having an official “dual system” of segregated schools. The northern states could not do this in the same way as the South, officially and on a large scale, regardless of whether or not anybody there wanted to, both because most northern states during the 1870s had official laws against segregated schools (whether or not they were being enforced) and also because many areas didn’t have large enough numbers of black people in general to populate a second school system. In rural areas especially, they barely had enough students to justify having even one school, with one room and one teacher. Many of the schools that we’ve seen described for this time period are rural schools and schools in small towns. Many of these small public schools were one-room schoolhouses, serving very small populations of students. Simply because of their overall low populations, not all small towns or rural areas in the northern states would even have black residents, and when that was the case, the issue of where to educate black people didn’t apply to them, and they likely didn’t have to give the matter much thought.

In cases where there were black families in a small town or rural area, there was just no other school or likely not even a second room at the local school to be used to segregate anybody. It was more a question of attending vs. not attending school. Most likely, under those conditions, any segregation would have been more unofficial, established and enforced directly by the attitudes and behavior of local people. Any black people in the area who didn’t feel welcome at the small local school or were actively discouraged from attending simply wouldn’t attend school at all, and because many areas either didn’t have attendance laws or rarely enforced the ones they had, probably no one would say or do anything about it. Their education and training for later life would come largely by engaging in manual labor of some kind and whatever else they could pick up along the way. (This is exactly the situation described for the titular black character in Stories of Rainbow and Lucky in the first installment of the series, written in 1859, on the eve of the Civil War. The white author was aware that things like this were happening in his time period.) The idea of non-attendance sounds bad and like it would set black people far behind white people in their area, and that’s true. However, even white kids during this time often skipped school or only attended sporadically if they were from farming families that needed them to help with farm chores or if they had to work to help support their families. The white kids would still have an advantage from the little schooling they had, but they were still likely to be farmers or doing manual labor, like their parents, rather than prioritizing education or looking to move up much in society or branch out into different types of work.

In larger towns and cities, there was more school choice because the populations there could support both public schools and fee-based private schools for those with the money to pay. Some former slave families went to the bigger cities in the north to find new opportunities and to escape the downsides of the environment they came from. In the larger cities, black people technically could attend public schools by law, although not necessarily without social pressure to not attend public schools with white children, and probably very little or nothing would happen if they didn’t attend because white families didn’t make them welcome or discouraged them from coming because, even in areas with school attendance laws, the laws were only weakly enforced and had loopholes. Where there was a sufficiently large enough population of black people, there was also more opportunity for the local authorities to find ways to segregate them in their neighborhoods. There were even cases where local school systems created some schools specifically for black students, which was illegal under the laws forbidding segregation in education, but could be managed if there was a sufficient number of black people in a particular area to make it seem justified to build a specific school, just for them. As long as they were living in concentrated areas, separate from white people, the segregation could be portrayed as simply providing a school for their particular area but which was meant to make sure that black children wouldn’t join the public schools white children attended. There was also the option for white people who had enough money to send their children to more exclusive private schools that black people would be unlikely to afford. In those instances, neighborhoods segregated by both race and economic status and the unequal ability to pay for a more exclusive form of education could separate well-to-do white families from poorer black counterparts, a form of economic segregation that is still a matter of concern in the 21st century.

There was also the issue that many black people didn’t entirely trust white schools because, having experienced exclusion and abuse, they thought that black children would be better nurtured by black teachers. Why fight too hard to be included in a school system that didn’t want them anyway and where the people there couldn’t be trusted and might just take advantage of them? In those cases, their solution was to form their own private schools or form private schools in conjunction with more sympathetic white organizations who shared common views and goals. If white people could sometimes start private schools out of their own homes or associated with their own churches (as explained in other chapters of this book), black people could do the same. (See Addy Learns a Lesson for a fictional example of a school for black children in Philadelphia during the Civil War.) The downside of this type of solution was that, in the 1870s, so soon after the end of the Civil War, slavery, and the laws that prevented many black people from being formally educated, there were relatively fewer qualified black teachers. Because the families of the students were also poor and struggling, these schools didn’t have much money. There were advantages to forming schools with the help of larger church organizations that also included white people or at least getting support from a larger church to form an all-black school. During the 1870s, state governments also created local colleges to teach people who had been freed from slavery, so the foundations were being laid during this period for more black people to become educational leaders for future generations. Conditions would still be rough and equal for a long time after this, but this period is important for laying the foundations of what was to come.

What I’ve described is just to give you a rough idea of the circumstances of racial segregation in schools and school systems in the 1870s and up to the Civil Right Movement, both in northern and southern states. It’s a complicated issue with a lot of variables. There is quite a lot more to be said about this, and because schools were always governed at the local level, there were considerable variations and options from place to place during every time period. It would be difficult to thoroughly describe every one of them in detail. However, I wanted to explain at least some of the broad strokes and varying conditions and attitudes to the issue to offer a broader view of what this book explains and what it doesn’t about race and education.