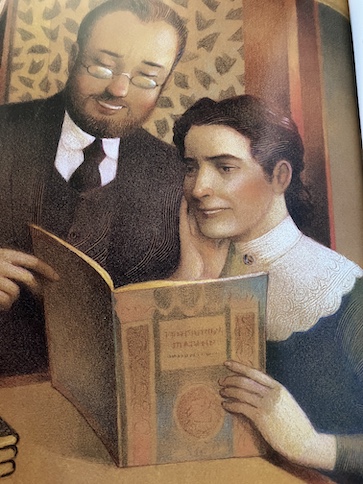

Look Up! by Robert Burleigh, illustrated by Raul Colon, 2013.

This picture book is about the life of Henrietta Leavitt, a “Pioneering Woman Astronomer” during the late 19th century and early 20th century.

The story says that Henrietta had a fascination with the night sky from a young age, often wondering just how high the sky was. When she got older, she formally studied astronomy, although most of the other students were men, and it was an uncommon profession for women.

After she graduated, she found a job with an observatory, although she rarely worked on the telescope. She was part of a team of other women who acted as human “computers”, doing basic calculations by hand and compiling information for others to use. Women like Henrietta were not expected to use this information themselves or draw conclusions from their own calculations, but Henrietta had her natural sense of curiosity and confidence in her ability to use her own mind.

She continued studying in her spare time, and while examining photographs of stars and doing her calculations, she began to notice some patterns that made her wonder about the explanations behind them. She studied an effect where stars seemed to become brighter and then dimmer, a kind of “blinking” effect.

She not only discovered that the existence of some of these stars had not been recorded yet, but she also found herself wondering about the pattern of this twinkling effect. Some stars appeared brighter and seemed to “blink” more slowly between bright and dim than other stars that weren’t as bright. By examining the relative brightness of the stars and the patterns of blink rate, she realized that it was possible to calculate the true brightness of the stars and use that to figure out how far away each star is from Earth. When she presented her findings to the head astronomer at the observatory, he was impressed. By using the chart Henrietta compiled, it was possible to calculate the distances of stars even beyond our galaxy. People of Henrietta’s time initially thought our galaxy might be the entire universe, but Henrietta’s finding shows that it was not and also that our galaxy is much larger than people thought.

The book ends with sections of historical information about Henrietta Leavitt and her discoveries and other female astronomers. There is also a glossary, some quotes about stars, and a list of websites for readers to visit.

My Reaction

I enjoy books about historical figures, especially lesser-known ones, and overall, I liked this picture book. The pictures are soft and lovely.

The only criticisms I have are that the book is a little slow and repetitious in places, and the subject matter is a little complex for a young audience. Some repetition is expected in picture books for young children, but how appealing that can be depends on what is being repeated. Henrietta’s work involves a lot of looking at pictures and figures and studying, so the text gives the feeling of long hours studying and “looking,” and many of the pictures are of her looking at books and examining photographs of stars through a magnifying lens. I found the story and pictures charming and in keeping with the Academic aesthetics, but I’m just not sure how much it would appeal to young children.

The story explains some of the concepts that Henrietta Leavitt developed and discovered, and it does so in fairly simple language. However, I still have the feeling that it would mean a little more to a little older child, who already knows something about astronomy, or to an adult like myself, who just enjoys the charming format of the story.

Part of me thinks that this story could have been made into a little longer book, perhaps a beginning chapter book, which would have allowed for a little more complexity. One of the issues with making the story of Henrietta Leavitt into a longer book is that, as the section of historical information says, “not a great deal is known about her life.” There just might not be enough known details about Henrietta’s life to put together a longer book.

Still, I really did enjoy the book, and I liked the presentation of 19th century astronomers and astronomical concepts. I especially enjoyed the way the story portrayed the concept of “human computers.” This type of profession no longer exists because we have electronic computers and computer programs that perform mathematical calculations faster than human beings can, but before that technology existed, humans had to do it themselves. “Human computers” had to work in groups to get through massive amounts of data and calculations, and it was long and tedious work, but their work was largely hidden from the public eye. As the story says, they were expected to do mathematical calculations and compile data, but they were compiling it for someone else’s use. Someone else would use their data to draw conclusions, and that person usually got the credit for whatever they discovered, ignoring all the people who did the grunt work that made it possible. Since women like Henrietta were more likely to be among the “human computers”, working in the background, they often didn’t get much credit for their work. The male astronomers were more likely to be the ones analyzing data and taking credit for the conclusions they drew, although they didn’t do the background calculations themselves. What made Henrietta different was that she stepped beyond the role of simply compiling information but also took on the role of studying patterns and drawing conclusions from the data she was compiling. She did all of it, from compiling data and making calculations to interpreting the data and laying out conclusions and discoveries from it.

Women once worked in similar positions as “human computers” at NASA. The 2016 movie Hidden Figures was about women working as “human computers” at NASA in the 1960s.

Top Secret by John Reynolds Gardiner, 1984.

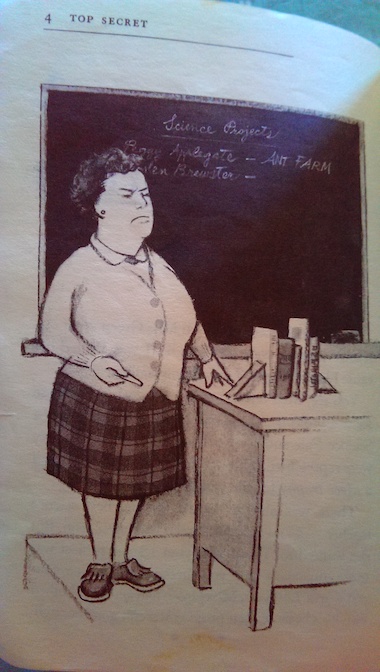

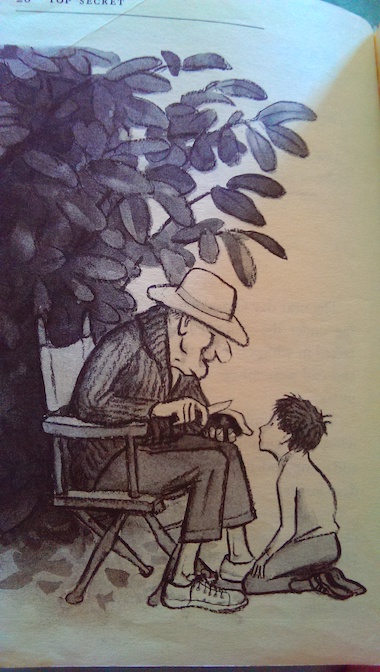

Top Secret by John Reynolds Gardiner, 1984. Allen is angry that Miss Green didn’t take him seriously, and lipstick is the last thing that he’s interested in. His parents think that he should just do the lipstick project and forget about it. Even if human photosynthesis were possible, how could a nine-year-old possibly achieve such a thing? Real discoveries are made by important men, not little boys. However, Allen’s grandfather encourages him to persevere in what he wants. He says that Allen has everything that a important man would have: five good senses and a brain that he can use to think. Allen’s grandfather often thinks about strange things himself, and he encourages Allen to think all the time.

Allen is angry that Miss Green didn’t take him seriously, and lipstick is the last thing that he’s interested in. His parents think that he should just do the lipstick project and forget about it. Even if human photosynthesis were possible, how could a nine-year-old possibly achieve such a thing? Real discoveries are made by important men, not little boys. However, Allen’s grandfather encourages him to persevere in what he wants. He says that Allen has everything that a important man would have: five good senses and a brain that he can use to think. Allen’s grandfather often thinks about strange things himself, and he encourages Allen to think all the time. Although Allen acts like he’s carrying out the lipstick project, with his parents’ help, he continues studying photosynthesis on the side. When Allen gets stuck on what to do next, his grandfather advises him to “think crazy,” to just let his mind explore possibilities and see what it comes up with.

Although Allen acts like he’s carrying out the lipstick project, with his parents’ help, he continues studying photosynthesis on the side. When Allen gets stuck on what to do next, his grandfather advises him to “think crazy,” to just let his mind explore possibilities and see what it comes up with.

Basil and the Pygmy Cats by Eve Titus, 1971.

Basil and the Pygmy Cats by Eve Titus, 1971. Now, Basil thinks that he and his associates are free to continue their other mission, finding the lost civilization of pygmy cats. However, that mission is fraught with danger and surprises, and they haven’t quite heard the last of Ratigan.

Now, Basil thinks that he and his associates are free to continue their other mission, finding the lost civilization of pygmy cats. However, that mission is fraught with danger and surprises, and they haven’t quite heard the last of Ratigan.