An Ellis Island Christmas by Maxinne Rhea Leighton, illustrated by Dennis Nolan, 1992.

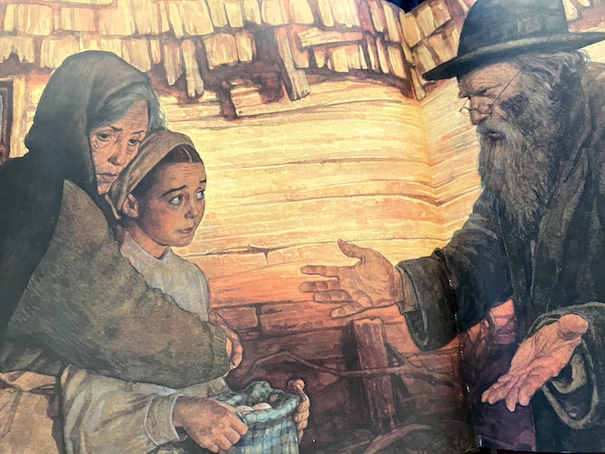

A six-year-old girl, Krysia Petrowski, knows that her family is preparing to leave Poland for the United States. Her father went ahead to America to establish a home for the rest of the family, and she knows that she, her mother, and her brothers will soon follow him. She doesn’t want to leave her home and her best friend, but her mother explains that life will be better in America because there is more food and there are no soldiers in the streets.

When the family begins packing to leave for America, they cannot bring everything with them because they have a long walk to get to the ship that will take them to America, and they can only bring what they can carry with them. The girl can only bring one of her two dolls with her, and she is sad at having to leave one behind.

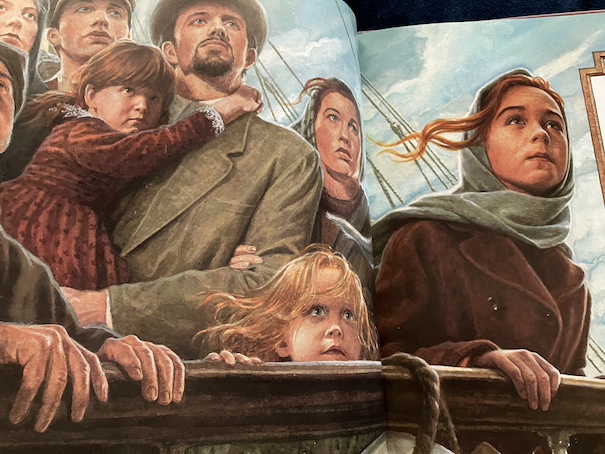

When they board the ship, the conditions are cramped and cold. The food isn’t good, either. The voyage is rough and stormy, and many people are seasick. The one bright point is that Krysia meets another girl she knows from school, Zanya, so she knows that she won’t be going to America alone and friendless. Krysia and Zanya play together on the ship when the weather is better.

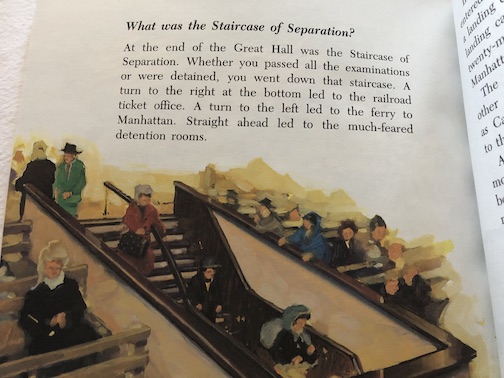

Finally, they reach Ellis Island on the day before Christmas. Everyone lines up, and the family has to show their papers to the immigration officials. Doctors look at them to make sure they are healthy enough to go ashore and into the city. Fortunately, they pass the health tests, although Krysia sees another woman who is told that she will have to go into the hospital or back to Poland because she is ill. The family converts their money to American money and buys some food. A man has to explain to them how to eat a banana because they’ve never seen one before.

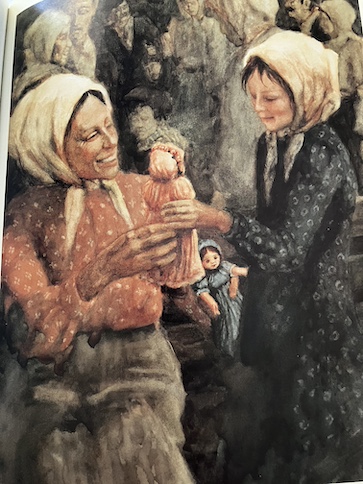

Because it’s Christmas Eve, there is a big Christmas tree, covered with lights and toys. There is also a man dressed like Santa Claus, although Krysia thinks of him by the Polish name, Saint Mikolaj. They don’t receive any new presents, but Krysia’s mother does have a surprise for her. The best part is when Krysia’s father comes for them and takes them to their new home.

The book ends with a section explaining the history behind the story.

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive (multiple copies).

My Reaction

The focus of this story is all on the feelings and experiences of the immigrant family, especially little Krysia. Krysia’s impressions of the journey and the arrival at Ellis Island are all a child’s impressions, and she often needs explanations of what’s happening and what’s going to happen next, which is helpful to child readers.

The historical context for the story is provided in the section of historical information at the end and in some hints during the course of the story. The section of historical information in the back of the book discusses the peak years of US immigration, from 1892 to 1924. They don’t say exactly what year this story takes place, but it mentions 48 stars on the American flag. That means that this is the early 20th century, after Arizona and New Mexico were admitted as states in 1912. During that time, 70% of US immigrants came through the immigration center on Ellis Island, just off the coast of New York City. Of those who arrived at Ellis Island, about a third stayed in New York, and the others spread out across the US. The family in the story seems to be going to stay in New York, but because the focus of the story is mainly on the journey, there are still few details provided about this family’s background and circumstances. The section of historical information also explains a little more about the traveling conditions of immigrants around that time and what typically happened at Ellis Island, so readers can understand how the experiences of the characters in the story fit into the experiences of other, real-life immigrants. (For more details, I recommend reading If Your Name Was Changed at Ellis Island and Immigrant Kids, nonfiction books which echo many of the details included in this book.)

There is some discussion in the section of historical information about the reasons why immigrants left their homes, and we told in the beginning of the story that there are shortages of food in Poland and soldiers everywhere, but there is more that I’d like to say about this. Because I like to add context to historical stories, I’d like to talk what was happening in early 20th century Poland and what’s behind the circumstances the characters describe. During the 19th century, parts of Poland were under the control of three different European empires: Russia, Prussia (a German state), and the Austro-Hungarian Empire (while later dissolved into Austria and Hungary). The oppressive control of these imperial powers accounts for the soldiers the family describes on the streets. There were Poles who resisted the control of these forces and wanted to reunify their country, so the soldiers were to keep the population under control and put down resistance. Around the turn of the 20th century, Polish territories were also suffering from unemployment and land shortages, which explains the food shortages the family experiences. Because of these conditions, there was massive immigration from Poland to the United States during the late 19th century and early 20th century. The Petrowski family in the story would have been on the tail end of this wave of immigration because circumstances changed for Poland after World War I (1914 to 1918), when Poland became an independent country again. Some Polish immigrants to the United States intended to stay only for a relatively short time, hoping to save up money and return to their homeland with the money to purchase land or improve their family’s circumstances, but many of these people remained in the United States anyway.

Because the main character, Krysia, is only six years old, she likely wouldn’t understand the full background of her family’s circumstances and the political causes of the hardships in her country, but I like to explain these things for the benefit of readers. I think it’s also interesting that this story is a Christmas story. We are never told what the religion of the characters is, although it seems that they are Christian because they care that it’s Christmas. Many people from Poland were Catholic, so it’s possible that this family was Catholic, too, but it’s never clarified.

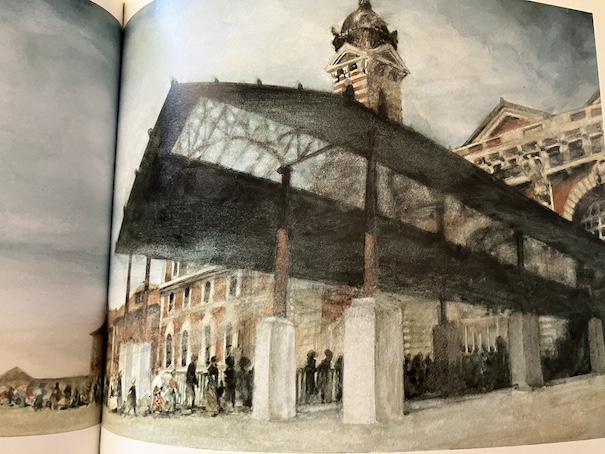

If you read the short biographies of the author and illustrator of the story, the author reveals that the inspiration for the story was the story of her own family’s journey from Poland. The illustrator says that he went on a tour of Ellis Island to prepare for producing the illustrations, and he tried to capture the “awe and anticipation” of the immigrants and the high vaulted ceilings and views of the New York skyline through the windows. I’ve also been to Ellis Island, and the illustrations in the book brought back memories of my trip there. I thought that the illustrator did a good job of capturing how big, impressive, and bewildering the Ellis Island compound would be to a young child.