A Sweet Girl Graduate by Mrs. L. T. Meade, 1891.

Don’t let the cover of this book fool you! Yes, it’s a 19th century novel for young girls, and there’s a strong morality aspect to the story, which is common for Victorian novels, but the story is not nearly so sweet and flowery as the cover indicates. This book is Dark Academia over 100 years before the term “Dark Academia” was coined and the genre/aesthetic became what it is today.

The story begins on an autumn evening. Priscilla (often called Prissie as a nickname) lives in a small country cottage with her aunt and her younger sisters, and she is packing to go to a college for young ladies. Her aunt isn’t sure about this recent trend of girls getting an education, but she is still proud of her niece. They discuss some last-minute advice for Priscilla, and although her aunt doesn’t have much money, she promises her a little extra as an allowance while she’s away. Priscilla says that she’ll write to her aunt, although probably not very often because she will be busy studying.

Priscilla’s three younger sisters will be remaining at the cottage with their aunt while she is away. Aunt Rachel, called Aunt Raby, is very strict, and the girls aren’t allowed to have much fun, so Priscilla’s sisters will miss her while she is away. Priscilla says that she will be at college for three years, and that she will visit when she can, at least once a year. Then, when she graduates, she will look for a good job so she can make a home for herself and her sisters together.

The younger sisters don’t entirely know it yet, but the stakes are high in the success of Priscilla’s education. Their father died when Priscilla was only 12, and their mother died when she was 14, which is when they moved in with their aunt. That was four years ago because Priscilla is now 18. There was a bank failure before their parents’ death which wiped out their savings, so the sisters have been entirely dependent on their aunt and her farm for support. The aunt works hard and has provided for their basic needs, although the family has no luxuries, and there was never really any expectation that the girls would have any education at all. However, Priscilla loves to read and has a talent for learning, so she has been teaching her younger sisters as best she can. The local minister, noticing Priscilla’s talent for learning and feeling fatherly toward her, has given her some extra tutoring in the classics, and he is pleased at how well she has managed the material.

The problem is that the girls’ aunt is now ill. She will not die from her illness immediately, but there is no cure for what she has (which is never explicitly named), and she and Priscilla know that she will die from it eventually. Over a period of two or three years, she will gradually become weaker, and she is already showing signs of that weakness. The aunt’s farm is legally entailed for another relative, so Priscilla and her sisters will not inherit anything from her and will have to find some way of making their own living after their aunt is gone. Priscilla goes to the minister and explains the situation, saying that she will have to stop her lessons and begin seriously learning skills that will help her find a job and support her sisters. She regards learning as a luxury that she will now have to go without.

Her first thought is that she should improve her sewing and become a dressmaker, but the minister can see that she doesn’t have much talent in that direction. He tells her that, besides being a pleasure, learning can also be a means of making a living. He thinks that Priscilla has the talent to become a teacher because of her learning ability and her skill in teaching her sisters. However, to become a teacher, Priscilla will need to attend college and graduate. At first, Priscilla doesn’t see how she can afford college, but her aunt sells her watch and the little jewelry she has, and the minister helps her take out a loan to pay for her education. He also helps Priscilla to study to pass the entrance examinations at St. Benet’s College for Women. Priscilla will need to do well in college for her sake and for the sake of her sisters’ future. People are depending on her, and she doesn’t want their help and sacrifices for her to have this chance in life go unrewarded.

The rest of the book is about Priscilla’s first year at college. During that time, she suffers from homesickness and social awkwardness because she has not been schooled in the intricacies of social manners and social classes. She confronts prejudice from the other students because she is poor, and they pressure her to act like they do and spend money as recklessly as they do. Priscilla has to learn to resist these pressures and temptations. It isn’t too difficult for her because she finds many of the girls at college to be shallow and not serious about her studies, and she doesn’t really admire them. However, she is soon befriended by a girl named Maggie, who is outwardly charming but inwardly miserable and complex.

Maggie’s friendship is often toxic to other girls, and Priscilla can see that she isn’t always honest and that she is not as devoted to other people as they are to her. She uses people for attention and affection, but Priscilla becomes fascinated with Maggie because she comes to realize that Maggie has layers and some of them are genuinely noble. For reasons that Priscilla doesn’t fully understand, Maggie is deeply troubled by the death of another student who once lived in the room that Priscilla now has at their boarding house. It seems like everyone at the boarding house is haunted by memories of Annabel Lee, and Maggie was once Annabel’s best friend. Maggie is moody and fickle in her temperament, and she hasn’t been truly close to many people since Annabel died, although she can charm people into do giving her attention and doing things she wants them to do. Priscilla has to be careful not to let Maggie manipulate her into getting into trouble, but she also benefits from Maggie’s friendship and has a way of bringing out Maggie’s better side.

During the course of the story, Priscilla has to face girls who don’t really want her at the college and who try to sabotage her socially and pressure her to leave. She also has to remind herself of her goals and the reasons why she came to college. When Priscilla is accused of a theft, both she and Maggie receive help from some mutual friends to realize the truth of what happened and the identity of the real thief, and Maggie is forced to confront a painful incident from her past that is still haunting her and which is the major reason why she acts the way she does.

There’s a lot more to unpack here, and I want to cover the story in more detail. If you’d like to stop here and read it for yourself, you can skip the rest of this.

The book is now public domain. It is available to borrow and read for free online through Project Gutenberg and Internet Archive (multiple copies, including an audio version). Later versions of this book were published under the title Priscilla’s Promise.

First Evening in The “Haunted” Boarding House

When Priscilla gets to college, she settles into her boarding house, which called Heath Hall and is run by Miss Heath. It isn’t until she gets to the boarding house that Priscilla realizes just how nervous and homesick she is. Because of her nervousness and the strangeness of living in a new place, she doesn’t present herself very well to the other students at first.

When she clumsily drops a coin, another student, Maggie, picks it up for her, and this is their first introduction. Maggie can tell right away that Priscilla is nervous and frightened, and her immediately impulse is to take Priscilla under her wing. Nancy, Maggie’s best friend, cautions her about how she treats new students. There are other students Maggie has been friends with when they first arrive, but she treats them like novelties. She acts like a friend and mentor for a couple of weeks, winning the girls’ confidence and making it seem like the start of a lifelong friends, and then tires of them and simply drops them. Nancy doesn’t think it’s right for Maggie to do this to the new girls, although Maggie brushes off her concerns. Nancy likes Maggie because she can be very sweet and fun, but she also recognizes that Maggie can be trouble, and she is sure that Maggie is going to recklessly cause some problems before she is finished with her education.

Maggie and Nancy notice that there is someone moving into the bedroom next to Maggie’s in the boarding house, and Maggie is upset because that room belonged to Annabel Lee. Annabel Lee was another student at the boarding house who was very popular with the other girls, but she tragically died of an illness. Nancy is practical and says that they couldn’t very well expect that room to be simply left vacant now that Annabel is no longer there. It’s just natural that the boarding house would rent it out to someone else eventually. Maggie is more emotional and says that they ought to have left it as a shrine to Annabel and that she is sure that she will hate the person who lives there. Nancy sighs, and when Maggie goes into her room, Nancy decides to introduce herself to the person who now occupies Annabel’s room, who turns out to be Priscilla.

Priscilla is unaware of who Annabel was, and she is still struggling with her nervousness and homesickness. Because Priscilla is trying to cover up for how nervous and awkward she feels, her manner just strikes Nancy as being cold and awkward, which makes Nancy feel awkward while talking to her. Nancy briefly introduces herself but doesn’t stay to chat long, although Priscilla secretly wishes that she had.

Priscilla continues to make mistakes through her first evening at the school. When she goes down to dinner, she enters the dining hall through the door that is normally reserved for the dons (teachers), and she sits at a table where the higher level students normally sit instead of with the other freshmen. Other students in the dining hall start talking about the nerve of some freshmen, getting above themselves, but Priscilla nervously isn’t sure what they’re talking about. Fortunately, Maggie decides to step in and help Priscilla.

Maggie sits next to Priscilla and gently explains to her what she did wrong. Miss Heath gave Priscilla a list of rules when she moved into her new room, and there was nothing about any of this in those rules. Maggie explains that there are certain, unspoken rules and customs among the students. Even though the students are supposed to be modern, liberal, and democratic by the standards of their day as part of this new generation of women seeking a higher education, Maggie admits that, deep down, they are still very conservative. She says this classist side of themselves shows itself whenever someone breaks their unspoken rules and social customs or steps out of their proper place. Priscilla thinks that the students at this school are cruel if they expect someone new to know rules that aren’t written or spoken about and that she is starting to wish she hadn’t come. Maggie hurriedly soothes her, saying that they’re not really that bad, and she invites Priscilla to her room to talk later so she can explain some things to Priscilla that she will need to know.

Nancy also steps in and tells Priscilla that most of the students take their tea up to their rooms after the meal, asking her if she would like to do the same. Priscilla, still nervous, decides that she will skip the tea tonight. Nancy says that, since this is the first night, she will want to spend the rest of the evening unpacking and that other girls in the boarding house will come to call on her. Priscilla asks her why they’re going to do that. Having lived on a farm, in a family that wasn’t very socially active, Priscilla knows less about social manners than she does about anything else. She isn’t accustomed to informal visits from people. Visits for her are usually more formal occasions, and she particularly has no idea what she’s going to say to these strangers who will be coming to call on her. Nancy, seeing that Priscilla is nervous and doesn’t know how to cope with the social aspects of the school and life in the boarding house, tells her that these are simply informal visits so the other students can introduce themselves to the new person in the boarding house. Nancy offers that, if Priscilla would like, she can spend the evening with Priscilla and help facilitate these introductions. Priscilla nervously murmurs that she would like that.

The boarding house is more luxurious to Priscilla than anywhere that she has previous lived, but it also feels cold and un-homelike to her. The other girls are bright and chatty, and Priscilla finds them a little overwhelming. When the other girls come to visit Priscilla, they also comment about Annabel, who used to live there, and how the room looks more bare without her and her things. It seems like the other girls are there mostly to see the room and remember Annabel than to see Priscilla, and Priscilla is too shy to know what to say to any of them. One of the girls kindly says that the place will seem better once Priscilla has really moved in and has a chance to add her own decorations. Another girl says it will never be the same as when Annabel was there, but the kind girl suggests some shops where Priscilla can find some room decorations and offers to go shopping with her.

Then Nancy arrives and intervenes, seeing how overwhelmed Priscilla is and encouraging the other girls to leave. Nancy offers to help Priscilla unpack and goes to borrow some matches from Maggie because Priscilla doesn’t have any to light a fire. Priscilla accepts the matches but tersely declines the offer of help unpacking because she doesn’t want Nancy to see how meager her possessions are. Nancy awkwardly says that she will wait in Maggie’s room and that Priscilla can join them for cocoa later. It’s a custom of the boarding house for the girls to have cocoa in the evening, and they often invite friends in the boarding house to their rooms to share cocoa and chat before bed. Maggie later calls Priscilla to join them for cocoa but refuses to enter Priscilla’s room herself, still too affected by the memory of Annabel.

Priscilla goes to Maggie’s room, and the girls have cocoa together. Nancy isn’t there because she has gone back to her room to do some work, and Priscilla finds Maggie charming. Maggie has a way of putting people at ease, and Priscilla finds herself telling Maggie about herself and her reasons for wanting an education. Before she leaves, Priscilla asks Maggie about Annabel because of what the other students have been saying about her. To Priscilla’s shock and surprise, Maggie immediately becomes distressed and refuses to talk about Annabel, bursting into tears. Fortunately, Nancy arrives and reassures Priscilla that Maggie will be all right. As Nancy walks Priscilla back to her room, Priscilla asks her about Annabel. Nancy doesn’t really want to talk about Annabel, either, but she tells Priscilla that Annabel was a very popular girl at school who is now dead, and she says that it’s better if Priscilla doesn’t talk about her now.

All the same, the other students at the boarding house won’t stop talking about Annabel Lee. Although Priscilla doesn’t really believe in ghosts, it feels to her like Annabel still haunts the boarding house and her room in particular. Everyone seems to have memories of her, and Priscilla’s presence and her occupation of Annabel’s old room brings them out. Priscilla is often left with the awkward feeling that she has somehow usurped Annabel’s place, or at least, that other students feel like she has. She wishes that she had been given some other room in the boarding house. Even Annabel Lee’s name reminds her of the song by Poe, which is familiar to Priscilla and which is about a love that survives beyond death. (I think the author picked that name on purpose because of the song.)

Before that first evening is over, Priscilla realizes that she has misplaced her purse somewhere. This is serious because it has her key in it and the little money she has. She goes looking for it, and she overhears Maggie and Nancy talking about her. Maggie assures Nancy that Priscilla will not replace Nancy in her affections. Maggie calls Priscilla “queer” (in the sense of “strange”) and admits that she is nice to younger girls at college because she craves their affection. Maggie says that it gives her “kind of an aesthetic pleasure to be good to people.” She knows that she has an ability to inspire affection in other people, and she absolutely craves seeing the look of grateful affection she gets from the younger girls she helps at school. Nancy asks her if she ever returns the love that she receives from other people, and Maggie says that she does sometimes. She says that she is very fond of Nancy and kisses her.

(Note: This conversation isn’t necessarily proof that this is a lesbian relationship, which would have been not only shocking but actually illegal in England during the time period of this story. The book was published in 1891, and later in the 1890s, Oscar Wilde was tried and convicted for homosexual acts, although part of his conviction was also that he committed acts with underage boys, which would still get him a conviction by modern standards.

Certainly, lesbians did exist during this period of history, and it’s possible the author might know more about it than she could explicitly state and may be basing the characters’ feelings off of people she knew or met herself. However, modern readers might want to hold off firmly deciding what the real relationship between Maggie and Nancy is because there are other factors that are revealed later in the story. In particular, Maggie is a complicated character, who cultivates relationships for attention and to fill some dark emotional needs, and these relationships are not honest because there is not necessarily any real affection or romantic interest behind them. Maggie does have a male admirer, who we hear more about later, and we also eventually learn why her relationship with him is complicated.)

Priscilla, who is a sincere girl of strong morals and deep affection, is shocked at the way that Maggie and Nancy talk to each other and about her, and she quickly returns to her room without finding her lost purse. She is angry about what she’s heard because, although both Maggie and Nancy have been friendly to her and helpful that evening, Priscilla can see that neither of them really likes her or cares about her. Maggie was just pretending to be nice just to get attention, and Nancy is jealous of her for the attention that Maggie has given her. Although these types of feelings are completely alien to an inexperienced and unsophisticated girl like Priscilla, she has just had her first taste of toxic friendship, and she is about to learn more.

Life at College and the Other Students

When Priscilla is unpacked, and her meager personal belongings begin to fill her room, she starts to feel a little more at home, and she even begins to enjoy some of the newness of the college experience. She has more freedom at college than she ever has before, although she realizes that there is still a routine to college life, and conscientious girls follow the routine and both the written and unwritten rules of college society.

The book explains that life at college is somewhat like life at school, but much less restrictive because the students are considered young ladies rather than little girls. The freshmen are about 18 years old and are expected to graduate at about age 21, so all of the students are expected to behave as young adults. They are not closely monitored, and no one hands out punishments to students for neglecting their studies or misbehaving in minor ways. (What happens when students misbehave in major ways is addressed later in the book.) Basically, as long as the students are not breaking any laws or explicit rules and are not causing anyone serious harm or seriously disrupting the life of the college, there is little intervention. The students are expected to manage their time at college and organize their social lives and relationships with others by themselves. They are also not restricted to the college or boarding house. They may leave the college at any time for shopping or social engagements, although it is considered polite to let Miss Heath know where they are going and when they will be back, and they must be back before lights out. Priscilla has never been to school before, and she finds the unwritten social rules and the personal machinations of the other girls the most difficult part of her education.

Every morning, the girls in Heath Hall get up and start the day with prayers in the chapel. Nobody makes them go to chapel, but they generally do anyway because it’s expected, and participation in the routine activities helps them get along better. Then, they go to breakfast, where they select the foods they want to eat because the meal is served in the style of an informal buffet. Then, the students look at the notice boards. There is one notice board for announcing the lectures for the day and another for student clubs and social activities. The students use these announcements to plan their day. The mornings are always for educational lectures. Sometimes, there are more lectures in the afternoon, but there are also sports, gymnastics, and social activities. Nobody checks attendance at any of the lectures or activities, and if someone chooses not to attend something, nobody checks up on them. They can have lunch whenever they like, between noon and two o’clock in the afternoon, and the students typically have their afternoon tea in their own rooms, sometimes privately and sometimes with guests. Students study privately in their rooms whenever they like, and there are club activities between tea time and dinner, for those who wish to participate.

Priscilla has difficulties with the other students because she refuses to participate in the social activities of the college or go shopping with the other girls when they invite her. She even turns down invitations from other girls to have cocoa with them in the evening and chat, like she did with Maggie that first night at the boarding house. Having learned more about what Maggie and Nancy are really like, she becomes cold and distant with them, discouraging their friendship, but she also turns down possible friendships with the other students.

One day, two of the students criticize her for being unfriendly and not participating in the social life of the college. Everyone has noticed that Priscilla hasn’t even put up pictures or decorative knickknacks in her room or even purchased comfortable easy chairs for visiting, like the other girls have. Nancy tries to defuse the building arguments and criticism by saying that they mustn’t criticize the “busy bees”, the serious, studious students at the college because they are the foundation the college was built on. However, the other girls complain that college is also for fun and socializing, and if Priscilla is smart, she’ll stop fighting it and start participating with the other students.

The other students are about to walk out on Priscilla during this argument, but Priscilla stops them and shows them what she really has in her room. She shows them her empty trunk and explains that she has no pictures or knickknacks to put up in her room. She also shows them the contents of her purse (which she did find after she lost it) and how little money she actually has. She hasn’t gone shopping with the other girls or bought things for her room because she simply can’t afford them. She is from a poor family, and she is serious about her studies because she has to be, and her future depends on it. She acts the way she does because this is the life she lives, and this is what is right for her and her situation. The other girls just don’t understand because most of the girls at college are from wealthier families, and they’re not in her position. Priscilla has realized that she’s different from the other girls, but she doesn’t admire the other girls because she has already seen that there are problems with their behavior and priorities. She openly lets them know that she isn’t intimidated by them and will not be pressured into acting like they do because she simply can’t. It wouldn’t help her with her life or goals. The other girls are embarrassed and a little ashamed of themselves for not realizing her situation and for their shallowness and frivolous privilege. They leave Priscilla without saying anything else.

Nancy reports this conversation to Maggie and says that she admires Priscilla for her bravery in standing up to the other girls. Nancy never liked those particular girls because they are shallow, but she never had the nerve that Priscilla had to tell them off in that matter-of-fact way. Maggie asks Nancy if she’s going to worship Priscilla now, and Nancy says no but that she still admires Priscilla’s bravery. Maggie says that she doesn’t want to hear more about it because she doesn’t like hearing things about “good” people and their virtues, something which bothers Nancy. Nancy tells her to stop pretending that she doesn’t like goodness and morality, but Maggie says she really doesn’t. Hearing about Priscilla especially bothers Maggie because, although Priscilla initially opened up to her, she has not shown that grateful admiration toward her since that first evening, when she overheard Maggie talking to Nancy.

Maggie also has an unhealthy attachment to the memory of Annabel, and it still seriously bothers her that Priscilla has Annabel’s old room. Maggie can’t bring herself to look into Priscilla’s room or be reminded about Annabel, for reasons readers still don’t fully understand. Everyone liked Annabel at school, and people are still haunted by her memory, but for some reason, it’s worse with Maggie than with anyone else. She privately thinks that she cannot really feel love since she lost Annabel. It seems like Maggie had a similar sort of unhealthy attachment to Annabel as Nancy now has to Maggie.

This is where we begin to learn what is really going on with Maggie and what makes her tick. Maggie is not a happy person on the inside. In fact, she thinks of herself as the most miserable student at the college. Inwardly, she doesn’t think of herself as being either a good or lovable person, in spite of her outward charm and ability to inspire people to love her. She doesn’t really love herself. That’s why she always craves expressions of love and devotion from others but doesn’t seem able to really form relationships with others and maintain them.

However, there is one thing that really makes Maggie come alive. She loves the intellectual life of college. She forgets her misery when she loses herself in reading and translating classical works. Even her joy of classical studies can’t entirely distract her from her worrying love life. It’s a somewhat open secret that Maggie has a male admirer who writes to her sometimes, and this is a source of jealousy for the other students, especially Nancy and Rosalind (another younger girl that Maggie has been cultivating as an admirer), who both view this young man as a rival for Maggie’s attention and affection.

Toxic Friendships and Social Manipulation

Although Priscilla recognizes that Maggie is a false person who is mainly nice to other people for some selfish fulfillment, she can’t help but be fascinated by her charm and intelligence. Maggie tries harder to get Priscilla’s attention because she still craves attention and affection, and she views Priscilla’s reluctance to give her what she wants sort of like her playing hard-to-get. Priscilla’s attempts to ignore her just make her want to try harder to win the prize she craves.

Miss Heath, who doesn’t seem to understand some of the unhealthy admiration other students have for Maggie, encourages Priscilla to not burn out on her studies and to give herself time to make friends like Maggie and to enjoy the social aspects of school life. She says that she has seen other serious students take on too much, burn themselves out, and fail to finish their education before. Priscilla, who has never been to school before, takes Miss Heath’s advice seriously.

Maggie discovers that Priscilla loves flowers, and she uses them to appeal to Priscilla’s love of beauty. She uses aesthetics and intellectual discussion to appeal to Priscilla’s love of study and the pleasures of learning. Gradually, Priscilla finds herself become more of a friend to Maggie. She confronts Maggie about what she heard Maggie and Nancy say to each other on their first night in the boarding house, but Maggie brushes away Priscilla’s concerns. She claims that she only said those things to punish Priscilla for being naughty by eavesdropping. Soon, Maggie and Priscilla are doing many things together, from going to church services together to having cocoa in Maggie’s room in the evening and talking about their studies. It seems harmless enough, and some people are a little relieved because Maggie had given up doing many things that she used to do with Annabel, when she was alive, because they reminded her too much of Annabel. It seems like Priscilla has somehow inspired Maggie to do things that had become emotionally painful to her, and some people think it’s nice that Maggie has found a new best friend and is moving on.

However, as I said, not everyone understands Maggie’s toxic friendships, the unhealthy attachment some of the other students have had to both her and the deceased Annabel, and her manipulation of other people. The ones who do understand these things are some combination of jealous and troubled, and Priscilla, who is still relatively naive, hasn’t grasped the precariousness of her social situation. She has to learn to walk a delicate line between staying true to herself and her goals and between staying on good terms with her new friends. It’s fine for her to like other people, like Maggie, but not to be led astray by them. She has also attracted attention from some other students who resent her and feel threatened by her.

The two girls Priscilla told off earlier about their wanting her to participate in frivolous social activities and spending money are bitter about their embarrassment and how Priscilla made them them look shallow by demonstrating her poverty and virtue. They’ve been going around the school, telling everyone the story of what Priscilla said, but casting Priscilla in a bad light. They try to make Priscilla seem like a self-righteous prig who is trying to shame them for participating in normal social activities. Their fear is that, if other girls at college like Priscilla and decide to imitate her, austerity will become the fashion of the day. They think that they will either not be allowed to participate in their social activities and forced to keep their noses to the grindstone from now on or will be shamed for having nice things in their rooms while Priscilla doesn’t. They don’t want to be pressured to give up these things or forced to study as seriously as Priscilla does, so they do their best to ruin Priscilla’s social reputation, discourage other girls from being her friend, and try to get other students to gang up on her.

Their efforts are partly foiled because Maggie is popular, and Priscilla has become Maggie’s special friend. Nancy is also Priscilla’s supporter because she was present during their confrontation with Priscilla and stands up for her against the other students. Although Maggie and Nancy seem to have a toxic friendship with each other, and Maggie develops a series of toxic friendships with other students, Maggie and Nancy become Priscilla’s protection against even more toxic students. Miss Heath and the teachers at the college also appreciate Priscilla and her work at the college. However, unbeknownst to Priscilla, the more shallow girls still resent her and are plotting against her.

Rosalind knows of the unhealthy attachment other girls at college have to Maggie because she also shares it. Rosalind is one of the younger girls Maggie has cultivated as an admirer but has largely neglected since she became tired of her and more interested in Priscilla. Maggie and Annabel were once the college’s power couple/friendship duo, although Annabel was the more popular of the two. Other girls even save pictures and autographs of Maggie and Annabel as souvenirs, like they’re celebrities, and Rosalind herself has a picture of Maggie that she sometimes kisses.

Since Annabel’s death from a sudden illness, Maggie has been the undisputed social queen, although Maggie’s thrill at the attention she receives is somewhat dampened by her sense of loss because she was truly attached to Annabel herself. She craves attention and admiration and can’t help but pursue it, but she doesn’t feel like she really deserves it. Not all of the other students really admire Maggie. Some of them see her for the manipulative girl she really is, and they get sick of hearing the others rave about her or talk about poor, tragic Annabel.

However, Rosalind’s resentment of Maggie’s indifference to her after manipulating her affections has made her admiration of her turn to hate. She tells another girl that she’s thinking that she should tell Miss Heath about the unhealthy attachment other girls have to Maggie and get her to put a stop to this Maggie admiration cult. (I would have been in favor of this, but sadly, that’s not what Rosalind does.) Then, Rosalind and the girls who resent Priscilla get the idea of ruining Maggie’s friendship with Priscilla and bringing them both down this way.

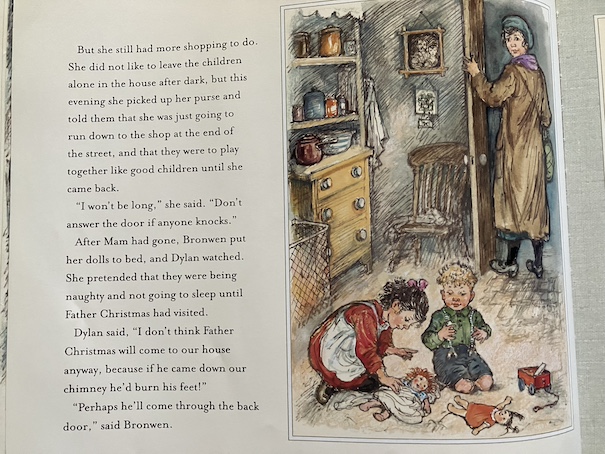

Rosalind tries to find ways to embarrass Priscilla socially and drive a wedge between Priscilla and Maggie. One day, she convinces Priscilla to go into town with her to pay her dressmaker, insisting that the dressmaker needs her money for her sick mother and that she wants company on the errand. Nancy tries to discourage Priscilla from going because the weather is bad and Priscilla has a cough, but Priscilla says that Rosalind talked her into coming. Since she promised, she has to go. Rosalind makes Priscilla wait in the cold and drizzle while she goes inside to pay the dressmaker and then takes Priscilla on another errand to see a friend before they go back to the college.

When they get inside this friend’s house, Priscilla realizes that Rosalind has tricked her into attending a party instead of just paying a short visit to a friend. Priscilla is under-dressed for this party and damp from her time outside, which is embarrassing. To make matters worse, Rosalind simply abandons her in a corner. Priscilla can’t bring herself to leave the party without Rosalind because she would be in trouble for returning to the college without her when everyone knows that they left together, and she can’t bring herself to search the party for Rosalind and demand that they leave because she feels out of place in her shabby clothes. She hears the fancy, catty women at the party gossiping about other women and the frumpy “girl graduates” of the college. Fortunately, the hostess of the party realizes that Rosalind has been treating Priscilla shabbily and makes her comfortable with some tea.

Then, Geoffrey Hammond, the young man who has been writing to Maggie, recognizes Priscilla and comes to talk to her. Priscilla explains her predicament and how Rosalind tricked her. Not only has Rosalind deprived her of study time by getting her to come to town on her errand and to this party, but if they don’t leave the party soon, they won’t get back in time for dinner, which would break one of the written rules of the college. Taking pity on her, Hammond goes to find Rosalind and talk to her. When he returns, he says that Rosalind has told him that she already told the principal of their college that they would be late for dinner, so they are excused. Priscilla is angry that Rosalind did this without talking to her, and she starts to create a fuss, but Hammond quiets her down, realizing that she is making a scene. He knows that she was nastily tricked, but he says, since they can’t get back to the college in time for dinner now, it would be more socially graceful for her to enjoy this party as best she can and then have words with Rosalind when they get back to college.

The two of them spend the rest of the party discussing The Illiad and The Odyssey. Priscilla shines in intellectual discussions about the classics, so Rosalind is a little jealous when she sees how well Priscilla is doing. She tries to ruin the moment by pretending that Maggie gave Priscilla a letter to give to Hammond and that Priscilla has either lost it or is withholding it. However, Hammond knows that Priscilla didn’t even know she was coming to this party and doesn’t fall for Rosalind’s story, disapproving of her. On the way back to the college after the party, Priscilla lets Rosalind know exactly what she thinks of her mean trick.

Later, at a cocoa party at the college, Rosalind tells the other students about the party, emphasizing Priscilla’s awkwardness and disdain of the fun. Then, she accuses Priscilla of flirting with Geoffrey Hammond. Everyone knows that Geoffrey Hammond is Maggie’s young man. The other girls don’t think Maggie treats him well, and some of them think they would be better for him, but they know that he’s devoted to Maggie. Rosalind is trying to make Priscilla look like a boyfriend-stealer.

The Auction

Meanwhile, one of the girls at the college, Polly, has gotten badly into debt. Although most of the girls at the college are pretty well-off, compared to Priscilla, even girls from wealthy families can get into trouble with money, if they’re not careful. Polly admits that her father told her not to spend above her allowance, but she is accustomed to spending freely. Now, she owes a considerable amount of money, and the only way she can think of to raise what she needs without telling her father what she has done is to sell some of the lovely things she’s bought to furnish and decorate her room and some of her fancy clothes. Her friends at the college, who all admire her nice things, are all eager to buy things from her. Their only concern is to remind her not to sell anything that would belong to the college, only her own belongings.

All of the girls at college, except for Priscilla, are invited to attend the auction. They exclude Priscilla because they know she doesn’t have money and they think “Miss Propriety” would snub the event and perhaps tell the principals about it. Really, the other students don’t think the principals of the college would approve of this auction, so they’re careful to keep the event secret from them. Originally, Maggie wasn’t planning to attend the auction, although she was invited, because she doesn’t know Polly and doesn’t care for this kind of auction. Then, Rosalind badgers her into going, saying that she has become too proper, self-righteous, and basically, no fun anymore. Maggie cares about her social reputation, so she decides to go to the auction, and to Priscilla’s surprise, she drags Priscilla with her. This turns out to be a bad thing for Rosalind because now Maggie is angry with her and determined to teach her a lesson.

Maggie doesn’t really want anything at the auction and resents being pushed into going, but because she is one of the richest girls at the college, she can afford to bid much higher for anything there than the other girls. She knows the things that Rosalind wants to buy for herself, so she purposely bids on the items that Rosalind wants. It’s bad enough when Maggie wins the bid for a sealskin jacket that Rosalind really wanted by bidding higher than Rosalind ever could, but it’s worse when Maggie intentionally ups the bid for some coral jewelry and then lets Rosalind win it at a price that’s higher than Rosalind can actually afford. Now, Rosalind owes money to Polly. Even worse, when Rosalind writes to her mother to ask for more money, her mother tells her to return the jewelry she bought and to send the money she’s already spent back to her. It was really more money than her mother could afford to give her, and she only lent it to Rosalind because Rosalind said that she could get a bargain on a sealskin coat, which is a valuable garment. The jewelry is more extravagance than Rosalind’s family can afford.

All of the girls who attended the auction get into trouble for being there because the activity wasn’t sanctioned by the college, and the heads of the boarding houses find out about it. That means that Priscilla is in trouble for attending, too, even though she didn’t buy anything. Nancy asks Maggie why she went when she knew it would probably be trouble, and Maggie says that Rosalind brings out her worst side.

Maggie hates herself partly because she knows that she has a good side and a bad side to her nature, and she finds it hard to manage or cover up her bad side. Sometimes, she just gets moody and temperamental. She doesn’t want to pretend to be good all the time, even though she knows she’s supposed to restrain her worst impulses to get along in society. That’s why she finds virtuous people so trying. She has a hard time struggling with her inner nature and doesn’t like herself. She can’t understand people who aren’t the same, who seem to find it easier and more pleasant to be good all the time and who aren’t subject to the same dark moods and temptations that she has. Even so, Maggie still considers good and proper Priscilla her friend because Priscilla is sincere in her friendship for Maggie and brings out more of her better side, and Nancy, who respects virtue, still loves Maggie, even knowing her complicated nature and how she feels about herself. So, while Maggie’s friendships with Nancy and Priscilla seemed toxic at first, when she was looking at it from the perspective of how she uses them to bolster her self-esteem, we start to see that there are positive sides to these relationships. Both Priscilla and Nancy care about Maggie, even when she struggles to care about herself or them, and they encourage Maggie to be a better version of herself.

The episode of the auction, while getting the girls into trouble is actually a turning point in Maggie’s character development. Polly, Maggie, Priscilla, and other girls from the auction are called before Miss Eccleston, the head of Polly’s boarding house, Katharine Hall, to explain themselves and the auction. Polly explains how she got into debt and couldn’t bring herself to ask her father for more money. Miss Eccleston lectures Polly about the need to manage her money better and avoid spending more than she can afford. Then, she questions Maggie about why she was at the auction because, as one of the senior students, she should know better. Maggie takes responsibility for her presence at the auction and also Priscilla’s, saying that Priscilla is only a new student at college and that she insisted that Priscilla come with her. Miss Eccleston asks Maggie what she bought at the auction and if she paid a fair price. Maggie admits that what she paid for the jacket was less than its true value. Maggie accepts responsibility for her actions and tries to shield Priscilla as much as possible from the fallout of the situation, not wanting her impulsive decisions to negatively affect her.

Miss Heath and Miss Eccleston lecture the girls about the importance of moral principles at the college, but Maggie stands up for herself and the other girls. She honestly admits that she is not proud of herself and her role in the situation. However, she points out that, although Polly’s debt was shameful and her abuse of the allowance from her father, her dishonesty about her spending to her father, and the secret auction were all improper, none of the students have actually broken any explicit rules of the college. Miss Heath and Miss Eccleston are concerned with disruptions to the the boarding houses and how the students’ behavior reflections on the college. Maggie’s argument is based on the fact that none of the students are children, and how they conduct their personal affairs isn’t the business of the college, even if they haven’t conducted themselves well here. Arguing with the heads of their boarding houses goes against their authority and is disrespectful, but Miss Heath and Miss Eccleston say that they understand Maggie’s point and will take it into consideration when they decide how they will proceed and what they will say to the college authorities.

The students themselves appreciate Maggie speaking up on their behalf, but they’re also divided in how they feel about the auction and even about Maggie’s defense of what they’ve done. Some of the students, who never took the auction seriously, think that Miss Heath and Miss Eccleston were making too much of the situation and that Maggie was right to tell them so. However, the more serious girls have realized that what they did was improper, and even though Maggie was trying to defend them from consequences, her defiance and disrespect of authority in the situation has broken one of the unspoken social rules of the college.

The social order that keeps everyone at college more or less in harmony has been shaken by the incident and by the students’ mixed feelings about the situation, and they’re not sure how to make it right. Some students think that the residents of Heath Hall should stand behind Miss Heath and Maggie and their position that, while the auction was inappropriate, the students have learned their lesson from the experience and should be treated leniently. Others think that it was all beyond the bounds of proper behavior, and they no longer wish to associate with Maggie because of her defiant attitude. The students who never attended the auction are irritated by the students who did because they think they are bringing scandal on the college, and by extension, on them. They don’t want to risk their families criticizing them or removing them from the school because they find out what happened and are scandalized by it. The students who weren’t at the auction didn’t do anything wrong, and they look down on the other girls for causing trouble. Everyone is unhappy that the harmony of the school has been shattered, and students are pressuring each other to take sides in the controversy.

Rosalind is even more vindictive toward Priscilla after the auction incident and tries again to blacken her name around the college. She tells the other students that Priscilla was the one who told the faculty about the auction and got them in trouble, even though Priscilla was there with them and is now in trouble, too. She also repeats the story of Priscilla flirting with Geoffrey Hammond at the party. Maggie knows that Priscilla said that Hammond was nice to her at the party, so she tries to ignore what Rosalind says, and Nancy makes it clear that she doesn’t want to hear Rosalind’s sour gossip.

The Fallout and Geoffrey hammond

The fallout of the auction incident causes some students to change their minds about their relationships with each other and some to change their behavior. Rosalind tries to ingratiate herself to Geoffrey Hammond because she likes him and tries to blacken Maggie’s name to him to ruin their relationship. Maggie’s affection for Priscilla sours when Priscilla insists on speaking privately with Geoffrey Hammond and that she doesn’t want Maggie to hear what she has to say. Maggie thinks that maybe Priscilla has designs on Geoffrey Hammond, but that isn’t the case. Really, Priscilla wants to have a frank talk with Hammond about both Rosalind and Maggie.

Priscilla likes Maggie, but having gotten to know her, she has a realistic sense of what Maggie is really like now, both her good side and bad side. She recognizes that Maggie is a flawed person, and this is what she doesn’t want Maggie to hear her say to Hammond. She tells Hammond that she finds Maggie fascinating because she has never before seen such a flawed person who also has such a sense of nobility. She doesn’t want Maggie to hear her speaking of her flaws, but like Nancy, Priscilla knows that Maggie has them and yet has likeable and honorable qualities, like the way she admitted her faults at the same time as she defended her fellow students to the heads of their boarding houses. Hammond understands what Priscilla means because he feels the same way about Maggie. Both of them also understand that Rosalind is dishonest, and Hammond believes Priscilla when she says that Rosalind is saying untrue things about Maggie to ruin her reputation.

Maggie’s behavior toward Priscilla becomes colder because of the suspicions that she harbors about what Priscilla said to Hammond. She continues to act as a friend, but she’s not as warm as she was becoming with Priscilla before. Hammond sees what’s happening between the girls, and he is critical with Maggie about the sealskin coat that she bought too cheaply from Polly. Maggie didn’t really want the coat originally, and she’s a little ashamed of having it, so she returns it to Polly. Polly says that she can’t afford to repay Maggie for it now because she really needs the money, but Maggie tells her not to worry about it. If she likes, she can consider the money a loan and repay her during the next school term, which pleases Polly. This is part of Maggie’s nobler side.

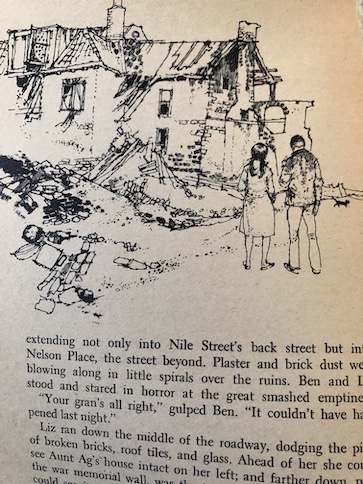

When Priscilla goes home for Christmas break and sees her aunt and sisters, they welcome her. Priscilla is astonished when she sees how rough and cramped the little cottage seems to her now that she has become accustomed to the beauty and comfort of the boarding house at college. When she notices how her aunt has become more sick, she feels guilty for her feelings. Her little sisters are upset about her returning to college, and one of them accuses her of forgetting about them and having fun in college rather than making any money. It’s true that Priscilla has been studying and not earning money yet, and she feels guilty that she hasn’t thought much about her aunt or sisters while she was away.

She confides all of this to the minister, and he says that he understands. He thought that she might have feelings like this because of all of the changes she’s been experiencing in her life and her new glimpse of the wider world and the possibilities of life that lay ahead of her. He says that what she is feeling is natural and that she’s over-analyzing it. Priscilla is just currently preoccupied by all the new experiences that she’s been having. She’s been adjusting to all the changes she’s experiencing, and her view of the world is wider now than the narrower one she had when she just lived on the farm.

Priscilla also tells him a little about her friendship with Maggie and how much influence Maggie can have over her, that sometimes she feels like she would do anything for her. The minister reminds her that she would also do anything for her aunt and sisters. This new relationship, like the new experiences she’s been having in college, is fascinating to her for its newness, but he doesn’t think that it has replaced her older and deeper affections. She may have temporarily found herself overwhelmed and preoccupied with everything that’s new to her, but what is deep and most important to her is what will last.

Priscilla worries whether it’s right for her to be away at college with her aunt so sick, but the minister insists that she go back to college and her studies because it’s still important to her future, and her aunt wants her to continue. Her aunt confirms this. She understands that Priscilla is bookish person, like her father. While she appreciates her niece’s care and devotion, she knows that her niece has a future ahead of her, and she wants her to build her future.

Ghosts of the Past and Paths to the Future

In spite of the now-strained friendship between Maggie and Priscilla and Rosalind’s resentment against them both, Priscilla must return to the college and finish her studies. Priscilla tells Maggie that she needs to give up the classical Greek studies that they both love and focus on modern languages instead. It pains her, but Priscilla knows that she has almost enough education for a teaching position, and she must focus on the most practical studies for getting a job as soon as possible for her sisters’ sake. For the first time, Priscilla fully explains to Maggie the true circumstances of her family. This revelation and their shared love of classical studies brings out Maggie’s better nature once again, and she is inspired to find a way to help Priscilla and her family.

However, Rosalind still has not returned the coral jewelry to Polly, has not paid Polly the money she still owes her, and has neither returned the money she borrowed from her mother nor obtained any more money from her. Rosalind is determined to keep the coral jewelry even though her mother has urged her to return it and get her money back, but she still can’t fully pay Polly for it. Polly has now gotten more money from her father during the Christmas break and wants her jewelry back, so she would be happy to buy it back from Rosalind for what Rosalind paid for it. It’s Rosalind’s pride and resentment that keeps her from returning the jewelry. When she has an opportunity to steal the money she needs to pay Polly what she owes from Maggie and frame Priscilla for it, she takes it, thinking that she can solve her money troubles and get revenge on the girls she hates.

Because Priscilla isn’t popular at college, many of the other students are inclined to believe the suspicions about Priscilla being a thief when the theft is discovered. Maggie initially worries that Priscilla might be the thief because she knows that Priscilla was in her room earlier and that Priscilla’s family badly needs money, but after observing Priscilla’s reactions and thinking it over, she regrets her suspicions. Nancy staunchly insists that she’s on Priscilla’s side. Even so, Priscilla is so embarrassed by the accusations that she wants to leave college, but Hammond persuades her to stay. He says that, if she leaves now, not only would she be depriving herself of her education, but running away would seem to confirm everyone’s suspicions. Hammond knows more about Priscilla than he has admitted because the minister who has been helping her is his uncle, and Maggie has told him things about Priscilla’s situation.

Maggie does some soul-searching and must confront her remaining feelings about Annabel’s death and about Geoffrey Hammond to resolve her feelings about Priscilla and herself. The truth is that Geoffrey Hammond was once a childhood friend of Annabel’s. Although Maggie is in love with him and everyone at college thinks of him as being her young man, she hasn’t felt free to express that love because, in her mind, she still thinks of him as being Annabel’s young man. Maggie is an orphan and an only child who is not close to her guardian, and before she met Annabel, she felt like she hadn’t truly known what love was. She just never had anyone to be close to before Annabel. Now that Annabel is gone, Maggie feels like she can’t truly love anyone else and has felt like it would be especially wrong to love Hammond, even though he expressed his love for Maggie before Annabel’s death. Maggie revealed to Annabel that Hammond had proposed to her shortly before Annabel’s death from typhus, and Maggie has felt guilty about it ever since, thinking that the shock of this revelation contributed to Annabel’s sudden death. This is a major root of Maggie’s self-loathing and rejection of budding relationships and real love. Maggie feels like she can’t accept Hammond and his love any more than she could originally accept Priscilla moving into Annabel’s old room. She almost wants to leave college herself because of it.

However, Maggie now can’t stand the idea of Priscilla giving up her classics studies, where she is sure she could shine as a scholar, and she tries to enlist Miss Heath in persuading Priscilla to continue. Meanwhile, Priscilla is not interested in Hammond for herself and tries to enlist Miss Heath in persuading Maggie to accept his marriage proposal because Hammond understands Maggie better than she thinks and genuinely loves her for it. Miss Heath says that she can’t make up the girls’ minds for them any more than the girls can make up each other’s minds. She knows that Priscilla has good reasons for focusing on practical subjects, and she doesn’t want to interfere with that, but she decides that she should talk to Maggie about Annabel. Fortunately, some of the other girls at the college are starting to suspect the truth about the theft of Maggie’s money, and an invitation to another party at the same house where Rosalind tried to embarrass Priscilla before reveals the truth to Maggie. Miss Heath’s final revelation about Annabel straightens out many things.

My Reaction and Spoilers

Early Dark Academia

One of the reasons why I wanted to cover this book was because it’s an early example of Dark Academia from over 100 years before this genre/aesthetic gained a name and became popular in the 2020s. Although people think of Dark Academia as a modern genre/aesthetic, it was built on Victorian aesthetics and very old concepts that have previously appeared in literature:

- The value of education (with the apparent conflict between learning for pleasure and learning for a profession and students who attend college for purposes other than education, like social activities)

- Class differences among the students (a major reason for the differences in the students’ purposes for attending college and what’s behind many of the unspoken social rules of college life)

- The nature of the friendships and relationships among the students.

Modern Dark Academia novels have all of these, but Mrs. L. T. Meade did it about 100 years earlier. Some aspects of human nature and education just haven’t changed much.

L. T. Meade was the pen name of Elizabeth Thomasina Meade Smith. She was born in Ireland and was the daughter of a Protestant minister. Later in life, she moved to London. She started writing at age 17, and she wrote more than 280 books in different genres. She was also a feminist and the founder and editor of Atalanta, a popular late Victorian literary magazine for girls. Although her writing was extensive, Meade is best known for her books for girls, especially school stories. Her school stories continued to influence school stories for girls after her death.

Modern readers of Dark Academia will appreciate all the literary references in A Sweet Girl Graduate, from classics like The Iliad and The Odyssey to Edgar Allan Poe and his poem Annabel Lee. Priscilla quotes the poem in the story, and I’m sure that the poem inspired the author to write about the memories of the dead student, which is why she gave the character that name.

From Toxic Relationships To Helpful Friends

In a modern Dark Academia book, a girl like Priscilla might be led astray by a girl like Maggie. However, in this book, Priscilla is not tainted by Maggie’s toxic friendship because she realizes that Maggie has toxic qualities, and she is determined to resist them. Early into her time at college, she makes it clear to the other girls that she won’t be pressured by them into changing herself, and that attitude is part of what keeps Priscilla from being too manipulated by Maggie. She does find Maggie’s charm harder to resist than the catty peer pressure of the other girls at college because it has more pleasant and helpful aspects. However, Priscilla has some very definite limits, and her knowledge that she has to be responsible and take her future seriously for her sisters’ sake as well as her own keeps her from doing anything too irresponsible.

Because Priscilla makes it clear that she won’t change herself to fit in for the sake of friendship or social cred, Maggie actually finds herself changing more to fit in with Priscilla. It isn’t harmful for Maggie to change because she is already unhappy with herself and truly needs to change the way she acts and the way she looks at life and love. She craves Priscilla’s attention and affection because it is harder to get than most people’s and also because, deep down, Maggie still craves a replacement for the love and support she had from her deceased best friend, Annabel, and someone who can help her redeem herself from the guilt she has felt ever since Annabel died.

Toward the end of the story, we learn that Maggie hates herself and cannot truly bring herself to feel affection for other people because she blames herself for Annabel’s death. Annabel died of a sudden but natural illness, but the day she fell ill was the day when Maggie told her that Hammond proposed marriage to her. Since Hammond was Annabel’s childhood friend, Maggie worried that maybe Annabel harbored feelings for him and that the shock of hearing that he really loved Maggie might have been too much for her in her weakened condition. So, although Maggie still craves love and affection, she has purposely shut herself off from returning affection to anyone, especially Hammond, since Annabel’s death.

By being her sincere self, Priscilla brings out Maggie’s better nature, reminds her that she has lovable qualities in spite of her imperfections, and shows her that not all relationships end in death or tragedy. Although Maggie starts out by being a toxic friend, Priscilla is the antidote to the toxicity, turning this story into one of redemption rather than corruption. Miss Heath completes Maggie’s self redemption and reconciliation with Annabel’s death by telling her that she spoke to Annabel shortly before she died. At that time, Maggie herself was sick, although she didn’t get as sick as Annabel did. Annabel told Miss Heath to tell Maggie that she was happy for her and Hammond. If Miss Heath had told Maggie what Annabel said immediately, it would have spared Maggie and the people around her a lot of pain. She just didn’t pass on the message because Maggie was sick at the time and because she didn’t fully understand what Annabel was talking about until Priscilla explained Maggie’s feelings to her.

When Maggie finds out that Rosalind was the thief, she confronts her and makes her apologize to Priscilla and leave the college. Maggie admits to Miss Heath that it was a bit high-handed of her to impose these consequences on Rosalind. Maggie may have overstepped her authority by sending her away from the college, but Miss Heath says that she approves of the way she handled the situation. If Rosalind had remained at the college instead of leaving quietly, Miss Heath would have had to take the matter to the college authorities, who would have publicly expelled Rosalind for her theft. A public expulsion would not only have embarrassed Rosalind and her family and brought legal consequences on Rosalind, but it would have also publicly embarrassed the college. It’s better for everyone if they can manage the situation quietly. Priscilla tells Rosalind that she forgives her before she leaves, and at the same time, because Victorian novels tend to deliver moral messages in strong terms, Priscilla also gives Rosalind a guilt trip about how “you have sunk so low, you have done such a dreadful thing, the kind of thing that the angels in heaven would grieve over” and reminds her of how her mother is going to feel when she finds out why Rosalind had to leave college. Rosalind says that she regrets not being Priscilla’s friend instead of her rival. She would be in a much better situation in the end if she had let Priscilla influence her for the better rather than becoming her worst to try to get the better of Priscilla.

I was left partly thinking that Maggie never really apologizes to Rosalind for the way she treated her. Maggie does feel guilty about what she did at the auction, driving up the prices so Rosalind would end up owing money. If she hadn’t done that, Rosalind might not have been motivated to steal the money. However, even before that, Maggie toying with Rosalind’s feelings, leading her on to get her attached to her and then dropping her, was messing with Rosalind’s mind. This was the sort of situation that Nancy feared and tried to warn Maggie about because Nancy understands even better than Maggie how strongly Maggie influences other people’s feelings. Maggie assumes that her temporary pets among the students will get over it when she leads them on, gets them somewhat emotionally dependent on he,r and then drops them, but some, like Rosalind, are damaged by the experience.

Nancy has a strong moral center, so even though there are times when she is too attached to Maggie and jealous about Maggie’s attention, she would never stoop to Rosalind’s kind of petty revenge. At first, Nancy’s relationship with Maggie seems more devoted than is healthy, but Nancy’s moral center is what keeps her from being corrupted by Maggie’s toxic friendship in the way that Priscilla’s knowledge of herself and her goals and situation save her from corrupting influences. Nancy loves Maggie, but even though she loves her, she’s not blind to Maggie’s flaws and not afraid to tell her when she thinks that she’s done something wrong or is taking a bad outlook. Victorian novels emphasize morality, and Nancy is one of the moral voices in the story. She sometimes acts as Maggie’s conscience and tries to help Maggie understand other people’s feelings, although Priscilla is the one who truly motivates Maggie to make changes to her life for the better. Nancy’s moral outlook and admiration for virtue also leave her open to admire other people besides Maggie, like Priscilla, and her admiration of Priscilla’s virtues is what soothes Nancy’s jealousy for her and makes her look at Priscilla as another friend instead of a rival.

The Atmosphere

The boarding house has a cozy, old-fashioned atmosphere, with fireplaces and stoves, tea and cocoa in the evening, and some charming room decorations. I thought it was interesting that the students all have beds that are meant to look like sofas, basically day beds. Priscilla is right that even the basic rooms are fairly luxurious. There are electric lights at the school, although the students also use fireplaces and candles.

However, Priscilla’s room also has that “haunted” quality because of the memories of the popular student who used to live there and died tragically young. When Priscilla first moves in, other students, especially Maggie, find it upsetting, and Priscilla gets the creeps because of the way the other students talk about Annabel and Annabel’s room. That haunted quality wears off as Priscilla makes the room more her own and asserts her own identity over it and her situation. Annabel’s haunting presence in the story ends when Maggie realizes that she did not contribute to Annabel’s death and that Annabel was her faithful friend to the end. She finally becomes reconciled to Annabel’s death and ready to move on with her life and accept the love of other people, including her new friends and the man she really loves and who has loved her all along. The story starts out Dark Academia but ends with Light Academia because the characters have learned important things about each other and themselves and are headed in better directions in life.

For part of the story, I had wondered if Maggie was going to go down the dark path in the story and if Geoffrey Hammond would turn his attentions to the equally intellectual but more virtuous Priscilla. However, I was relieved in the end that Maggie resolved her inner turmoil and that Hammond stayed faithful to her. Priscilla never tried to steal her friend’s boyfriend and was only concerned for their mutual welfare and happiness as her friends. I liked the happy ending and how the story ended with more cozy feelings than angst and regrets.

So, Were Any of the Characters Lesbians?

I don’t really think so. I can’t completely swear to it, but based on the time period, the habits of people at the time, and the ending of the story, I don’t really think that the author was trying to imply that. If they were lesbians or bisexual, there is nothing that states it explicitly, although modern readers could read that into the situation. I can’t 100% declare it’s impossible, but the original Victorian readers of this book probably wouldn’t have drawn that conclusion themselves because they were probably not inclined to think that way about people in general since that sort of thing would be a taboo subject that young Victorian women reading this story might not have fully understood.

The characters’ interactions can be open to that interpretation by modern readers, but there are factors of the time period and the characters themselves to take into account. It’s important to acknowledge that the ways people spoke to each other and interacted were different during this time period. For modern people, kisses between teenagers or adults who are not related to each other are almost always romantic, but this book shows that this is not necessarily the case. Many people kiss each other in platonic ways during the course of this book. It seems to be a general way for women in particular to greet each other or express affection. Many friends kiss each other, and there are even times when Miss Heath will give students a kiss, which college staff and faculty would never do in the 21st century because for fear of giving people the wrong impression. We don’t regard that kind of exchange as appropriate or professional in modern times.

Various characters are enamored of Maggie because Maggie is a charismatic character who knows how to attract attention and get people to admire her. However, in the end, Maggie accepts Hammond’s offer of marriage and admits that she really loved him all along. We don’t know whether Nancy, Priscilla or Rosalind end up with boyfriends/husbands or not. The story ends with Priscilla determined to finish her studies and support her sisters, and Rosalind leaves college in disgrace because of her theft.

What might look like romantic crushes between females in this book ultimately turn out to be extreme girl crushes or cult of personality/toxic friendships. It seems to me that Maggie’s charisma helped her build a kind of cult of personality among her fellow students, where she was almost hero-worshipped or treated as a kind of school celebrity. Some of her friends are jealous of rivals for her attention and possessive of Maggie, which could indicate something deeper, but it’s not definite. Many of the girls are inwardly insecure at this time of their lives and separated from family and other friends while they’re at college, and a major part of Maggie’s appeal is her ability to put people at their ease, soothe ruffled nerves, and get people to depend on her for a boost of self-confidence, affection, and reassurance. Maggie fulfills people’s emotional needs, when she isn’t too preoccupied with her own emotional turmoil, so the attachment the other students experience to Maggie may be a reflection of their need for that type of emotional support rather than romance.

I’m pretty sure this is the explanation for Rosalind because Rosalind is not particularly happy and confident by herself. She attaches herself to Maggie because she craves her support and possibly envies her for the money and social status. Rosalind gets in over her head at the auction because she’s trying to buy status symbols. She tries to embarrass Priscilla and blacken her reputation to make herself look better by comparison, but it ultimately fails because she goes too far and commits an actual crime. Even before then, not everyone liked her underhanded behavior and toxic gossip. I’m pretty sure that Rosalind was after Maggie’s friendship and was upset at being snubbed by her because she felt dependent on Maggie for her own popularity and insecure emotions.

Only three people in the story seem to see Maggie for what she is, both her good and bad sides, and love her for it. Those people are Nancy, Priscilla, and Hammond. Hammond’s interest is definitely romantic love. Priscilla is fascinated by Maggie’s complex and contradictory character, and she wants to see Maggie happy. Nancy might come the closest to romantic love, but even that’s not definite. It could still be devoted (and occasionally excessive) friendship. Like Priscilla, she seems to appreciate Maggie’s complex character, although she also tries to do a little damage control when she sees that Maggie is likely to leave some emotional messes behind her because of the way she handles her relationships.

If this book were made into a movie today (entirely possible because it’s public domain), it wouldn’t surprise me if at least some of the characters were interpreted as lesbians or bisexual. Personally, I just think that the author was trying to make more of a statement about charismatic personalities and emotional manipulation.