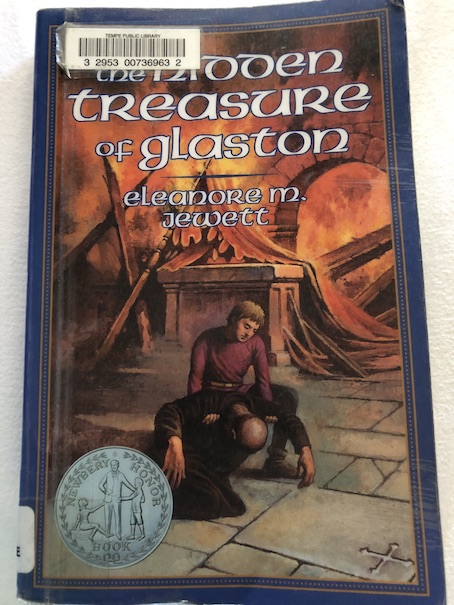

The Hidden Treasure of Glaston by Eleanore M. Jewett, 1946.

The

year is 1171. Twelve-year-old Hugh, a

somewhat frail boy with a lame leg, arrives at the abbey of Glastonbury with

his father on a stormy night. Hugh’s

father is a knight, and in his conversation with Abbot Robert on their arrival,

he makes it known that, although he loves his son, he is disappointed in the

boy’s frail condition because he can never be a fighter, like a knight’s son

should be. The abbot rebukes him, saying

that there is more to life than war and that he, himself, is also of noble

blood. The knight apologizes, and says

that, although it is not really the life that he would wish for his son, he asks

that the abbey take him in and educate him.

Although the knight (who refuses to give his name, only his son’s first

name) says that he cannot explain his circumstances, the abbot senses that the

knight is in trouble and is fleeing the area, perhaps the country of England

entirely.

It is

true that the knight is in trouble, and he is fleeing. Since Hugh’s health is delicate, his father

cannot take him along in his flight.

Realizing that the abbey will provide him with a safer life, Hugh’s

father wants to see him settled there before he leaves and gives the abbey a

handsome gift of expensive, well-crafted books as payment for his son’s

education. The abbot is thrilled by the

gift, although he says that they would have accepted Hugh even without it. Then, the knight leaves, and the monks begin

helping Hugh to get settled in the abbey.

Hugh is upset at his father’s leaving and the upheaval to the life he has always known, although he knows that it is for the best because of his family’s circumstances. Although the story doesn’t explicitly say it at first, Hugh’s father is one of the knights who killed Thomas Becket, believing that by doing so, they were following the king’s wishes. Hugh’s father did not actually kill Beckett himself, but he did help to hold back the crowd that tried to save Beckett while others struck the blows, so he shares in the guilt of the group. Although Hugh loves his father, he knows that his father is an impulsive hothead. Now, because of the murder, Hugh’s father is a hunted man. By extension, every member of his household is also considered a criminal. Their family home was burned by an angry mob, their supporters have fled, and there is no way that Hugh’s father can stay in England. However, the prospect of life at the abbey, even under these bleak circumstances, has some appeal for Hugh.

Hugh has felt his father’s disappointment in him for a long time because his leg has been bad since he was small, and he was never able to participate in the rough training in the martial arts that a knight should have. Even though part of Hugh wishes that he could be tough and strong and become the prestigious and admired knight that his father wishes he could be, deep down, Hugh knows that it isn’t really his nature and that his damaged leg would make it impossible. Hugh really prefers the reading lessons he had with his mother’s clerk before his mother died. His father always scorned book learning because he thought that it was unmanly, something only for weak people, and Hugh’s weakness troubles him. Hugh’s father thinks that the real business of men is war, fighting, and being tough. However, at the abbey, there are plenty of men who spend their lives loving books, reading, art, music, and peace, and no one looks on them scornfully. For the first time in Hugh’s life, he has the chance to live as he really wants to, doing something that he loves where the weakness of his bad leg won’t interfere.

The abbot is pleased that Hugh has been taught to read and arranges for him to be trained as a scribe under the supervision of Brother John. Hugh enjoys his training, although parts are a little dull and repetitive. Hugh confides something of his troubles in Brother John, who listens to the boy with patience and understanding. Although he does not initially know what Hugh’s father has done, Hugh tells his about the burning of his family’s home, how they struggled to save the books that they have now gifted to the abbey, and how there were more in their library that they were unable to save. Hugh tells Brother John how much he hates the people who burned their home and how much he hates the king, who caused the whole problem in the first place. His father would never have done what he did if the king hadn’t said what he said about Thomas Becket, leading his knights to believe that they were obeying an order from their king. Brother John warns Hugh not to say too much about hating the king because that is too close to treason and tells him that, even though he has justification for hating those who destroyed his home, he will not find comfort in harboring hate in his heart. He also says that not all that Hugh has lost is gone forever. People who have left Hugh’s life, like his father, may return, and there are also many other people and things to love in the world that will fill Hugh’s life. Brother John urges Hugh to forget the past and enjoy what he has now. When Hugh says how he loves books but also wishes that he was able to go adventuring, Brother John says that adventures have a way of finding people, even when they do not go looking for them.

One

day, when Brother John sends Hugh out to fish for eels, Hugh meets another boy

who also belongs to the abbey, Dickon.

Dickon is an oblate. He is the

son of a poor man who gave him to the abbey when he was still an infant because

he was spared from the plague and wanted to give thanks to God for it. Dickon really wishes that he could go

adventuring, like Hugh sometimes wishes, although he doesn’t really mind life

at the abbey. Because Dickon is not good

at reading or singing, he helps with the animals on the abbey’s farm. Although he is sometimes treated strictly and

punished physically, he also has a fair amount of freedom on the farm,

sometimes sneaking off to go hunting or fishing. He also goes hunting for holy relics. Dickon tells Hugh about the saints who have

lived or stayed at the abbey and how the place is now known for miracles. He is sure that the miracles of Glaston will

help heal Hugh’s leg, and he offers to take him hunting for holy relics. Hugh wants to be friends with Dickon, but at

first, Dickon is offended that Hugh will not tell him what his last name

is. Dickon soon realizes the reason for

Hugh’s secrecy when a servant from Hugh’s home, Jacques, comes to the abbey to

seek sanctuary from an angry mob that knows of his association with Hugh’s

father.

The abbot

grants Jacques temporary sanctuary but tells him that he should leave the country

soon. When Dickon witnesses Jacques’s

explanation of why the mob was after him, comes to understand his connection to

Hugh. Although the mob does not know

that Hugh is actually connected to Jacques, Dickon spots the connection and

tells Hugh that he forgives his earlier secrecy. Dickon even helps Jacques to leave the abbey

the next day, in secret.

Now

that Dickon knows Hugh’s secret, he lets Hugh in on his secrets and the secrets

of the abbey itself. He shows Hugh a

secret tunnel that he has discovered.

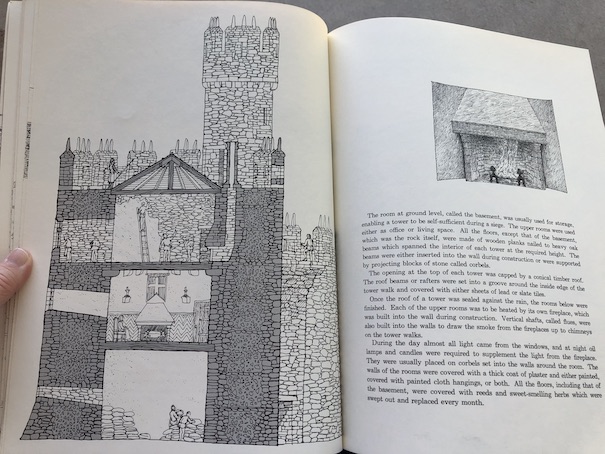

There is an underground chamber between the abbey and the sea where more

parchments and some other precious objects are hidden. Dickon doesn’t know the significance of all

of the objects, although there appear to be holy relics among them. Dickon’s theory was that monks in the past

created this room and tunnel to store their most precious treasures and get

them away to safety in case the abbey was attacked and raided. At some point, part of the tunnel must have

collapsed, blocking the part of the tunnel leading to the abbey. The boys are frightened away when they hear

the ringing of a bell and can’t tell where it’s coming from. Could there have been someone in a part of

the tunnel that is now blocked off from the part where they entered?

Since Hugh is sworn to secrecy concerning Dickon’s discovery, he can’t ask Brother John about it directly, but he gets the chance to learn a little more when Brother John asks him to help clean some old parchments so they can reuse them. Most of them are just old accounting sheets for the abbey that they no longer need. Brother John said that they were stored in an old room under the abbey. Hugh asks Brother John about the room and whether there are other such storage rooms underground. Brother John says that there are rumors about a hidden chamber somewhere between the abbey and the sea where they used to store important objects for safety, but as far as he knows, no living person knows where it is or even if it still exists. Hugh asks Brother John about treasures, but as far as Brother John is concerned, the real treasures of the abbey are spiritual. However, when Hugh notices some strange writing on one of the parchment pieces that doesn’t look like accounting reports and calls it to Brother John’s attention, Brother John becomes very excited and orders him to stop cleaning the parchments so that he can check for more of the same writing. Among the other scrap parchments, they have found pieces that refer to Joseph of Arimathea, who provided the tomb for Jesus after his crucifixion. According to legend, Joseph of Arimathea also took possession of the Holy Grail, the cup that Jesus used at the Last Supper, which was supposed to have special powers, and that he left the Middle East and brought the Holy Grail to Glaston, where it still remains hidden. This story is connected to the legends of King Arthur, who also supposedly sought the Holy Grail. The parchments may contain clues to the truth of the story and where the Holy Grail may be hidden.

This story combines history and legend as Hugh and Dickon unravel the mysteries of Glastonbury and change their lives and destinies forever. Although Hugh and Dickon both talk about how exciting it would be to travel and go on adventures, between them, Hugh is the one whose father would most want and expect his son to follow him on adventures and Dickon is the one who is promised to the abbey. However, Hugh loves the life of the abbey and serious study, and Dickon is a healthy boy who is often restless. Their friendship and shared adventures at the abbey help both Dickon and Hugh to realize more about who they are, the kind of men they want to be, and where they belong. Wherever their lives lead them from this point, they will always be brothers.

There are notes in the back of the book about the historical basis for the story. In the book, the monks find the tomb of King Arthur and Guinevere. Although the story in the book is fictional, the real life monks of Glastonbury also claimed to find the tomb of King Arthur. The bones they claimed to find were lost when the abbey was destroyed later on the orders of Henry VIII, but this documentary (link repaired 2-27-23) explains more about the legends and history of King Arthur. The part about Glastonbury is near the end.