Ruth Fielding

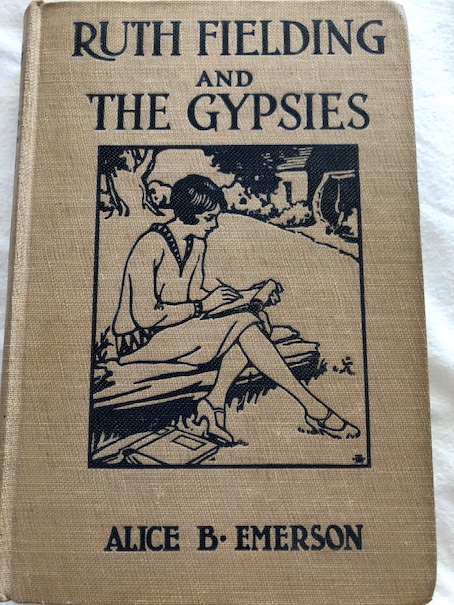

Ruth Fielding and the Gypsies; Or, The Missing Pearl Necklace by Alice B. Emerson (Stratemeyer Syndicate), 1915.

Just as a quick note before I begin to describe the plot of this book, this book is part of the Ruth Fielding series, an early Stratemeyer Syndicate, before they started writing some of their more popular and best-known series, like the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew. Some books in early Stratemeyer Syndicate series are awkward because they use racial terms that polite people would not use now. During the mid-20th century, around the time of the Civil Rights Movement, the Stratemeyer Syndicate revised the books it had in print, updating the technology and slang terms in the stories to be more modern and removing or altering some questionable racial terms and attitudes. Unfortunately, the Ruth Fielding series had already ended by that time, and these books were not among those that were revised and updated. I’ve explained this before on the pages for some the Stratemeyer Syndicate book series and individual book reviews, but I have to explain it again here because some people might object to the word “gypsy.” I know that’s not really the correct or polite way to refer to the Romany or “Travelers”, as they’re sometimes called, but it can’t be helped here because the Stratemeyer Syndicate put it right in the title. This is one of those books where I just can’t avoid it, and it’s all through the book. Some of the attitudes and stereotypes around the characters are also likely to be objectionable, but I’ll address that further in my reaction section.

The Ruth Fielding series is interesting because it was kind of a precursor to Nancy Drew, with a similar type of heroine, but one that, unlike Nancy Drew, grew up, went through school, and had a career during the course of the series. There are some aspects of this series and the development of the characters that I think were better done in this series than in the Nancy Drew series. There are also times when the books are surprisingly thoughtful about the conditions of life and society in the early 20th century, when they were written, and this book and the next one begin to mark a turning point in the main character’s life. Ruth is a poor girl, and before her education is over, she will have to seriously consider her career options, which is something you don’t see much in the Stratemeyer Syndicate series that are still in print because those characters never age. The characters in the earlier series did, which is why those series ended. There are some things in the series that I don’t like, like the racial terms and attitudes and when the stories are more adventure than mystery because I really prefer mystery, but this is what the books are like. In these reviews, I’m just explaining what the books and characters are like. On the bright side, if you don’t like what the books are like, you can consider that I read and reviewed them, so you don’t have to. You can find out what they’re like from my reviews and save yourself some time.

The Plot

Ruth Fielding is with her Uncle Jabez in a boat on the river near the Red Mill where they live when the boat overturns. Uncle Jabez falls out and hits his head. He almost drowns, but Ruth holds his head above water. She can’t pull him out of the river by herself, but she calls for help and attracts the attention of a passing gypsy boy. The gypsy boy, called Roberto, pulls Uncle Jabez out of the water.

Uncle Jabez is grateful, but the incident brings back an earlier argument about whether boys are more useful than girls. Uncle Jabez argues that boys are more useful than girls because they are stronger and can do heavier work, and he thinks that his near-drowning proves that. Of course, Ruth, Aunt Alvira, and Ruth’s friend Mercy are all offended by that assessment. Aunt Alvira points out that the boy who helped Uncle Jabez wouldn’t have been able to do that if Ruth hadn’t already been holding his head above water and calling for help. Ruth says that not all work is heavy work. Uncle Jabez says that girls are costly because they need money for education, and they’re not likely to have careers afterward, like men do. Ruth says that the reason why she wants an education is so that she can have a career and support herself.

Ruth knows that a poor orphan like her is lucky that she can attend boarding school with her friends. Her friend, Helen, is from a wealthy family, who is willing to fund her education in anything she wants to study, whether it eventually produces money or not, but Ruth doesn’t have that luxury. Eventually, she will have to get a job of some kind. Aunt Alvira says that, when she was young, most girls got a basic education and then got married, which is probably what Uncle Jabez is expecting Ruth to do. However, Aunt Alvira knows that modern girls have more ambitions. (Keep in mind that this story is set around 1915, contemporary to the time when it was written.) Ruth’s music teacher at school thinks that Ruth has a promising voice, and she wonders if she can train as a singer, although that’s not the kind of thing that her uncle would think of as something useful.

Before returning to boarding school with her friends, Ruth goes on a car trip with Helen and Helen’s twin brother, Tom. It turns out to be an unexpectedly eventful trip. Not long after setting out on the trip, they meet up with Roberto again and begin talking with him. The others ask Roberto about being a gypsy and if he wouldn’t prefer a more settled life with a regular job. Roberto says that, while he could work as a farmhand easily enough, few people would hire him for other jobs because he’s a gypsy, and people don’t trust gypsies. Besides, he sees little use in such a life. Tom says that he could afford better food and better clothes if he had a better job. Roberto says that he does well enough traveling around with his family, taking odd jobs, and helping his uncle at horse trades. He tells the others a little about his family and his life with them. After he leaves, Tom makes jokes about the rumors of gypsies kidnapping people.

Further down the road, Tom accidentally hits a lamb in the road with his car. The lamb is still alive, but its leg is broken. The farmer is angry, says that the lamb is useless now, and demands that Tom pay for the lamb. The price he demands is about twice as high as it should have been, but Tom pays it anyway to avoid further trouble. Then, they learn that the farmer, who doesn’t want to be bothered nursing the lamb until it heals, plans to simply kill it and feed it to his dogs. The girls are upset about the poor little lamb, and they plead for its life. Ruth is sure that the lamb can be healed. The farmer says that the lamb is his to do with as he pleases, but Helen points out that the lamb isn’t his anymore because Tom just paid for it. The farmer protests, but they take the lamb anyway. At first, Tom says that he doesn’t know what else to do with the lamb except take it to a butcher, but the girls persuade him to let them keep the lamb and try to help it.

Later, there is a storm, and the group seeks shelter in an old, empty house. The girls go inside while Tom parks their car in an old shed. The girls find the house spooky and wonder if it could be haunted. In some books, investigating a haunting in an old, abandoned house like this would be the main mystery, but in this one, it’s just one episode that gives them a clue to something else. While the girls are exploring the upstairs rooms and Tom is still outside, two strange men enter the house. The girls don’t let the men know they’re there. They’re not sure of who the men are or what their intentions are, so they listen to their conversation. They can’t understand everything the men say because half of their conversation is in an unfamiliar language, but from what the girls understand, they have either committed a theft or are going to be involved in one. The girls don’t want the men to find them or Tom, so they scare them out of the house by spooking some bats, which take flight and frighten the men away.

All of this would be exciting enough, but as they all travel further, Tom’s car breaks down. Tom leaves the girls and sets out on foot to get some help. The girls wait at the car for him, but it starts getting dark, and they start to get worried. A group of gypsies passes by with their wagons, and although Ruth isn’t sure it’s a good idea, Helen asks the gypsies if they can give her and Ruth a ride to her parents’ house. The gypsies ask the girls some questions, and then, they agree that the girls can come with them. Helen leaves a note for her brother that they’ve gone with the gypsies, but when she isn’t looking, one of the gypsies takes the note and destroys it.

It turns out that Ruth’s concerns about the gypsies were justified. The leader of this gypsy band is an elderly woman, who the girls recognize from Roberto’s stories as his grandmother, although Roberto is not currently among the group. The grandmother is a greedy woman, and she has realized from the girls’ car that at least one of them is from a wealthy family. To her, that means that they have relatives who would be able to pay a ransom for the girls. The girls become captives of the gypsies. The old woman also has an ability to hypnotize people with her eyes, and Helen seems particularly susceptible to it. During the night, while spying on the old woman, Ruth also learns that she is involved with the thieves they saw in the empty house.

The girls try to escape from the gypsies, and Helen gets away, but Ruth is caught. The old woman makes Ruth disguise herself as one of the gypsies so no one will notice her among the others. Can Ruth find a way to escape, or will Tom, Helen, or Roberto manage to help her?

This book is now in the public domain and available to borrow and read for free online through Project Gutenberg.

My Reaction and Spoilers

The Mystery/Adventure

The story covers not only Ruth’s adventures but the adventures of Ruth’s friends while she is captive, including Tom’s encounter with a suspicious farm couple and Helen’s frightening experience on a whitewater river. In the end, Roberto does help Ruth to escape. By the time Ruth returns to her friends and is able to tell her story to the authorities, the gypsies are well out of the area.

However, there is still something that bothers Ruth. She knows that Roberto’s grandmother had a valuable pearl necklace in her possession, apparently the spoils of the theft that the men in the empty house were talking about. Ruth wonders who they robbed and where the necklace came from. At first, it seemed like this plot line was going to be left hanging, but when Ruth returns to boarding school with her friends, she gets the answer. A new student is joining the school, Nettie Parsons, and she is the daughter of a multi-millionaire who made his money in sugar. She is the one who was robbed of the pearl necklace, which really belongs to her aunt, and there is a $5,000 reward for its return. $5,000 would be a pretty decent reward even in the 2020s, but it went much further in the 1910s. Ruth realizes that she knows who has that pearl necklace, and if she can get it back for Nettie, she would not only be doing a good turn for a classmate but getting the much-needed reward for herself. $5,000 would be enough to give Ruth some monetary independence and could fund her continued education.

Like other early Stratemeyer Syndicate books, the story is more adventure than mystery, although there are some mystery elements. Ruth gets some of the clues to the theft that the gypsies committed, but it’s more by coincidence than investigation that she discovers who the pearl necklace belongs to. Ruth does get the reward in the end, which allows her to finish at Briarwood Hall and go on to college in later books. However, while the old woman was apprehended with the necklace on Ruth’s information, I think it’s important to note that Ruth does not chase her down and apprehend her herself. Ruth is still at boarding school when others do that on her behalf, and she is then summoned to identify the apprehended suspect. On the one hand, this would never happen that way in a modern, 21st century book. In modern books, the girl heroines are much more active and would insist on catching the bad guys themselves. On the other hand, I have to admit that the way the book did it would actually be the more likely way this situation would play out in the real world, with the boarding school kid just providing information and being kept at boarding school while others apprehend the criminals. I think if the book was rewritten in the 21st century, Ruth would be more active in catching the criminals and retrieving the necklace, but there is some realism in the way the book actually ends.

Ruth’s career ambitions are not resolved in this story but are addressed more directly in the next book in the series.

Stereotypes and Racial Attitudes

I was curious about the notion that gypsies kidnap people because I’ve read about that in other books, and I wondered where that idea came from. According to an article that I found, it seems to come partly from traveling gypsies being used as scapegoats for missing or murdered children (like in old movies, where the small-town sheriff is anxious to blame a “drifter” for a crime) or as “bogeymen” in stories parents told to scare their children into not wandering away from home and also partly from people noticing children among traveling Romany groups who did not seem to resemble the people raising them, particularly if the children seemed to be lighter-skinned or have lighter hair or eyes than the adults. The reasons for the children not looking like the adults have been proven in modern times to be because the children were either adopted or were simply biological children who didn’t look like their parents through quirks of genetics, which sometimes happens. Light-colored eyes and light-colored hair are recessive traits, while dark eyes and dark hair tend to be more dominant traits, but even a dark-eyed, dark-haired person can carry the recessive genes for light hair and eyes, and those recessive traits can come out in the next generation. Basically, the children resemble previous generations in the same family, such as grandparents or great-grandparents, and if observers could see all the generations of the family together, it would be more clear how the traits were handed down to the children. (People also used to think that it was impossible for two blue-eyed parents to have a brown-eyed child, but that also happens sometimes because genetics can be complicated, eye color can be influenced by combinations of multiple genes together, and genetic mutations sometimes take place.) Basically, some people overreact when they see a child who doesn’t match the adults they’re with and start imagining kidnapping, but often, there are other, logical explanations, and being too quick to scream “kidnap!” causes problems. Some people do this to families who have had interracial adoptions. Personally, my brain would be more likely to consider possible divorces or previous relationships or possible affairs or maybe that the adult was actually a hired caretaker rather than a parent to be the next most-likely explanations after adoption for children who don’t look like parents, and I wouldn’t be eager to publicly ask questions about the sexual or reproductive history of total strangers. Unless the child appeared to be in immediate physical danger or was screaming, “Help!” or “This isn’t my daddy!” or something similar, I would be unlikely to interfere. “If you see something, say something” can be helpful, but it also helps if what you see is the big picture.

I also noticed that the gypsies in the story are described as being non-white people because they have darker skin, and even Ruth seems to dislike them and be suspicious of them for that alone. Granted, these particular people are actually criminals in the story who kidnap Ruth and Helen, but Ruth was thinking that just from looking at them. While I would have understood Ruth being reluctant to trust them because they’re strangers and because they know from the men in the empty house that there are thieves in the area, it’s their darker skin that bothers Ruth first. When Ruth first meets Roberto’s grandmother, Ruth thinks that the gypsy woman is too dark and strange/foreign to be trustworthy, and she later hates that her gypsy disguise involves bare feet and her skin dyed darker. She is ashamed of the way she looks in that disguise and thinks that she would be embarrassed for Tom to see her looking like one of the gypsies. Ruth’s prejudices bothered me more than if another character had done it because, while the older Stratemeyer Syndicate books do have inappropriate racial language and attitudes, the characters who are outright racists are typically the ones the stories show to be unfriendly antagonists or outright villains. From what I’ve seen so far, it’s rare for a friendly main character to be outright disparaging of racial appearances even if they have stereotypical notions about other people.

It’s really an irony that Ruth has prejudices against non-white people because the beginning of the story involves an argument with her uncle about his prejudices about girls. If this book had been written, or at least revised, during the 21st century, the rest of the story would have involved overturning both sets of prejudices. In the book as it is, nobody’s prejudices seem to be proven wrong.

Uncle Jabez’s assertions about girls’ usefulness go largely unchallenged. The girls are kidnapped when they’re by themselves, after Tom leaves them alone. Ruth copes decently with her captivity by helping Helen escape, but she needs help to escape herself, and men apprehend the criminals in the end, not Ruth herself. If Ruth’s uncle has any rethinks about the relative usefulness of boys and girls, he doesn’t mention it, and he isn’t presented with any strong evidence in favor of girls. Ruth is just content that she got the reward money for the return of the necklace, so she isn’t solely dependent on miserly Uncle Jabez’s grudgingly-given support.

There are no prejudices about gypsies proven wrong in the story. While I’m sure that most real-world Romany are not kidnappers, the gypsies in the books are criminals and kidnappers. Roberto is fond of his family and their traveling lifestyle, but at the end of the book, he accepts a new job as a gardener at Ruth’s school. He cuts his hair more like mainstream American styles of the time, and he starts wearing more mainstream American clothes. Ruth notes that his skin is still darker, but she is happy about these other changes. It is revealed that Roberto’s family came from Bohemia (a region now part of the Czech Republic) about ten years before, and his grandmother will now be deported back there, but Roberto wants to stay in the United States. He Americanizes his name and starts having people call him Robert. That’s quite a conversion from his attitudes much earlier in the book. Granted, having relatives arrested for theft and kidnapping can have an effect on a person, but from his earlier descriptions of his grandmother, I’m pretty sure that these sort of situations are not new to Roberto’s grandmother and the rest of their group. Maybe getting caught is new, but there is an implication that his greedy grandmother has done shady things before for the sake of money. But, part of the happy ending of this story is that Roberto gets assimilated into mainstream American society and becomes less ethnic, which is bound to leave a bad taste in the mouths of modern Americans.

So, Did I Like the Book?

I liked parts of it. As I pointed out, there are things in this book that are highly problematic for modern people, and I think the book as it is would be more suitable to adults who are interested in nostalgic children’s literature or the evolution of children’s literature. However, there are parts of the book I did find interesting, and I can see ways in which the book could be rewritten to make it both more exciting and more acceptable to modern people. For example, I really liked the part with the empty house where they overheard the thieves talking and the way the girls scared the thieves with the bats. If I were rewriting the story, I would extend that scene and leave out the part with the lamb, which didn’t contribute much to the rest of the story.

Of course, I would just have the criminals be part of a random criminal gang, not Romany. (How common were traveling caravans in the early 20th century anyway? I’ve never seen even one in real life. Was that really a common thing at one point so that it ended up in so many children’s books? From what I’ve read about Romany populations and migrations in the United States, some of the stereotypes about them had some basis in fact, like that some of them occasionally resorted to stealing to survive, but were exaggerated in the press for the sake of sensationalism, so I’m thinking that the prevalence of gypsy caravans and fortune tellers were probably also greatly exaggerated in literature.) I picture the criminal gang organized with the two guys who hide out in the old house being the thieves, and the others being a seemingly-ordinary and pleasant-looking couple who act as the fences of their stolen goods. Then, the girls could hitch a ride from this nice-looking couple after their car breaks down. At first, they wouldn’t know there was a connection between the “nice” couple and the thieves, but they would later accidentally see the couple talking with the thieves and the thieves handing over their goods. The girls would get caught spying on them, so the criminals would kidnap them because the girls now know too much.

Later, after the girls get away from the criminals, Ruth could find out that the necklace they saw being handed over wasn’t among the thieves’ belongings when the police caught up with them. Thinking about the place where the thieves were caught and something she may have heard them say, she could then realize that the thieves doubled back on their trail after the girls escaped from them, returning to their hideout in the abandoned house to hide the necklace because they still don’t know that the girls were in the house when they were talking there before. Then, Ruth could sneak away from her boarding school for a day to go back to the house and look for the necklace, finding it in a clever secret hiding place. I think that arrangement of events would make Ruth more active in solving the mystery, better justifying her acceptance of the reward at the end.

Mystery of the Golden Horn by Phyllis A. Whitney, 1962.

Mystery of the Golden Horn by Phyllis A. Whitney, 1962.