Annie’s Promise by Sonia Levitin, 1993.

This is the final book in the Journey to America Saga. Annie, the youngest of the Platt girls, is more of a tomboy than her older sisters. Her father thinks that she’s been growing up too wild in America, running around and climbing like a boy. This summer, in 1945, while her best friend goes to visit their family’s farm in Wisconsin, Annie’s father wants her to stay home and help him with sewing for his coat business, and Annie’s mother has a list of chores for her to do. It all sounds so boring and dreary. Twelve-year-old Annie longs for excitement, but because of her recent appendix operation and her migraine headaches, her parents worry about her health.

Then, Annie gets the opportunity to attend summer camp. She wants to go and do all the fun summer camp activities that other girls do, but her parents worry at first. They worry about Annie’s health, and they don’t know who is running the camp or what they do there. Annie’s older sisters, Ruth and Lisa, tell their parents that it’s normal for girls in America to go to summer camp and that the experience might do Annie some good. When the family doctor says that Annie is healthy enough to go, her parents finally agree.

At first, camp is hard. Annie faints soon after her arrival, and she worries that maybe her parents were right about her being delicate. However, one of the counselors tells her that these things happen and that she was probably just overtired, overheated, and still suffering from the rough bus ride to the camp and that she will be fine after she rests. Annie is physically fine, although one of the other campers, Nancy Rae, makes a big deal about the incident, calling Annie a “sickie” and other names. Nancy Rae is a terrible bully, and Annie nearly drowns in the lake after accepting a dare from Nancy Rae to swim across it, in spite of not being a good swimmer. Annie overhears the counselors saying that Nancy Rae should probably be sent home for goading Annie into a dangerous stunt, but they know that Nancy Rae comes from a bad home and that her father abuses her. For her own sake, they decide to give her another chance.

However, even knowing Nancy Rae’s troubled history doesn’t help Annie when Nancy Rae keeps picking on her and a black girl named Tallahassee (Tally, for short). Nancy Rae calls Tally and her younger brother (who is also at the camp) “nigger” and says that Annie is a “nigger-lover” when she tries to protect the younger brother from one of Nancy Rae’s tricks that could have really hurt him. (Note: I’m not using the n-word here because I like it. I’m just quoting because I want you to see exactly how bad this gets. Nancy Rae uses this word multiple times, and so do others when quoting her. This book is not for young children. Readers should be old enough to understand this word and beyond the “monkey see, monkey do” kind of imitation some kids do when they learn about bad words. The management assumes no responsibility if they aren’t.) Nancy Rae is a thrill-seeker, who frequently does wild stunts to get attention and tries to make other girls hate Annie as much as she does. At one point, she snoops through Annie’s things and tries to take her diary. Eventually, she figures out that Annie is Jewish and makes fun of her for that, painfully reminding Annie of what it was like living in Nazi Germany and of her relatives, who died in the concentration camps.

Finally, Annie reaches the breaking point with Nancy Rae. At a camp talent show, she arranges with other kids to dump horse manure on Nancy Rae’s head after she finishes singing a song. Nancy Rae is so humiliated by the experience that she ends up leaving camp. Annie is relieved that she is gone, but one of the camp counselors, Mary, makes her feel guilty about her revenge because she sees Annie as being stronger and more talented than Nancy Rae and wishes that she could have made Nancy Rae her friend instead, giving the bully a chance to improve herself. (I disagree with what the counselor says, but I’ll explain more later why.) Annie feels badly about how things turned out, but the incident blows over, and the rest of camp is a great adventure for her.

At camp, Annie mixes with different kinds of children from the ones she usually sees in her neighborhood and at school, and everything is a learning experience. She becomes friends with Tally and gets a crush on a boy named John. There is an ugly incident in which an assistant in the camp kitchen tries to molest Annie when he finds her alone (this really isn’t a book for kids), but the camp counselors dismiss him for what he did. Annie and Tally talk about many things together, and Tally is very understanding. The incidents with Nancy Rae and the kitchen assistant bring up the subjects of people who try to victimize others and how to deal with them. Annie resents that people like that force others to be on their guard, limiting them in ways that they can behave in order to avoid being victimized, but Tally says that there’s no help for that. As long as people like that exist, she says, protecting yourself is a necessity. They also compare the way Annie feels when John gives her a little kiss to the repulsed and frightened way that she felt when the kitchen assistant tried to force himself on her. Both incidents involved a kiss, but the way it was delivered and the person delivering it made each experience feel very different. In the end, Annie’s crush on John turns into friendship rather than love as she realizes that the kiss was just a friendly gesture. It is a little disappointing to her at first, but it is still a learning experience for her.

Annie learns that everyone at this camp has been through something bad in their lives. Annie’s family are war refugees, but Tally’s father has been married three times, and she’s often the one to take care of the house and her younger brother, while her current stepmother cleans other people’s houses for money. Other kids are poor or orphans or have fathers in jail. The camp gives them a chance to get away from their problems for awhile, to make new friends, and to develop talents that they can be proud of. Annie really blossoms at camp, learning to ride horses and work on the camp newspaper. As Annie’s session at camp comes to an end, Mary offers Annie a position as a junior counselor for the final session of camp, helping the young children. Annie is enthusiastic about the prospect, but family dramas at home threaten to derail her plans. Ruth’s fiancé is shell-shocked from the war and has broken off their engagement. Lisa is tired of arguing with their parents about every small piece of independence in her own life and has decided to move to a place of her own. With all of this going on, and their parents upset about everything, what chance is there that they will sign the permission slip that Annie needs to become a junior counselor?

This book shows how much the lives of the girls in the Platt family have changed since they first left Germany for America. It’s partly because they are living in a different country, partly because times and habits are changing everywhere, and partly because all of the girls are growing up and making decisions about what they really want to do with their lives. The older girls in the family, Ruth and Lisa, are women now and thinking about careers and marriage. As the girls suffer disappointments and changes of heart, their parents suffer along with them, and Annie realizes that she has to make up her own mind about what she really wants. As Annie tries to decide what she really does want, her parents struggle to cope with all of the changes in their daughters’ lives and in the changing world around them. They fight against it in a number of ways, and when things go wrong, whether it’s Annie’s illnesses or the older girls’ romantic problems, they tend to get angry or panic. As the book goes on, it becomes more clear that what the parents really feel is helplessness. More than anything, they’ve wanted life to be better for their daughters in their new country, and it upsets them when things don’t work out. They want to help guide their daughters and make their futures work out for the best, but in the process, they often come across as too controlling or making the wrong decisions because they don’t fully understand the girls’ feelings or situations.

Ruth and Lisa each suffer romantic disappointment before they settle down. Ruth had a fiancé, Peter, who went away to fight in World War II, but having seen the prisoners in the concentration camps, he has returned disillusioned and dispirited. He was Jewish, but now comes to associate his religion and heritage with pain and suffering and wants to give it up, breaking off his engagement to Ruth in the process. At first, Ruth is angry with him, saving that it’s like he wants to give up on his whole life, on the whole world. The girls’ father says that he wants to kill Peter for leading his daughter on, but part of his feelings turn out to be his own feelings for somehow failing his daughter, that he is somehow to blame for allowing this disappointment. When Lisa is upset because the young man that she’s been seeing says that he doesn’t want to get married, she argues with her parents about the course of her life and leaves home to live on her own. Her parents see that as turning her back on their love and protection, but Lisa says that she just wants the independence that other girls have. Even Annie feels abandoned by Lisa because Lisa was always there to comfort her as a sister and help her persuade their parents to listen to her, but Lisa says that she has to deal with problems on her own and that Annie will understand someday, when she’s in the same position. Annie realizes that, in a way, she already is in the same position.

The one time that Tally comes to visit Annie at her house and the girls go to the beach together, Annie’s parents make a scene when she gets home because she’s left sewing all over the house and eaten more food than she should have. Tally was going to apply for a sewing job with Annie’s father, which would have helped both of them, but Annie’s parents send her away, thinking that she’s a bad influence who encouraged Annie to goof off. Then, Annie hears her own parents use the n-word. It’s the final straw for Annie, and she runs away to camp.

The people at camp are glad to have her because they need her help, but being there, helping them, and thinking about her own life and future help Annie to realize what’s really important to her. She’s been feeling bad about the hate she got from Nancy Rae and the hate that she felt from her parents with their insults to her friend. However, her parents don’t really hate her, and in spite of what they’ve done, she doesn’t really hate them. She realizes that, before she does anything more with the camp, she needs to go back and see them.

Annie rethinks what Nancy Rae was really about, how she was filled with hate for everyone, dealing out hatred because of all that she’d received from everyone else. The counselors realized that she needed love more than anything, but Nancy Rae’s own hateful behavior pushed away the people who would have given her more positive attention and Annie’s revenge (although provoked) ended her camp experience. Annie realizes that she doesn’t want to go down the same path and that she must mend her relationship with her family.

I said before that I disagreed with the counselor’s approach to the problem of Nancy Rae and what she said to Annie about her revenge. I see what they were trying to do with giving Nancy Rae another chance, but what bothers me about it is that they act like Annie was in a much less vulnerable position to Nancy Rae and that she should have been strong enough to take what Nancy Rae dished out without hitting back, and I don’t think that’s true. All of the kids at the camp were there because they had something troubling in their lives, some vulnerability, including Annie. To say that Annie was more fortunate and more talented and that it should have been enough was to discount the harm that Nancy Rae was doing. I know that the counselors were trying to make the camp experience positive for Nancy Rae, but she was making the camp experience more negative for everyone else around her and needed to be stopped. Everyone suffers from something in life (as this book also demonstrates), but not everyone chooses to become a bully because of it. Nancy Rae made that decision herself, within herself, and for herself alone.

Part of the problem, I think, was that there were no obvious consequences for Nancy Rae’s bad behavior, and therefore, she had no reason to stop doing what she was doing. The lack of punishment and the inequity of the situation was what finally sent Annie over the edge with her. Since the counselors didn’t make it obvious that Nancy Rae was in the wrong, Annie felt that she had to, and that says to me that there was a lack of responsibility and accountability. I think that life is a balance and that both positive reinforcement (giving rewards to people who do good) and negative reinforcement (punishment for bad behavior) are necessary. I believe in plain speaking, and if I were in the counselors’ position, I would make it plainly and specifically clear that no campers were to use the n-word, to mess with others’ belongings, or to do the other things that Nancy Rae was doing and that there would be consequences for doing so, telling them exactly what those consequences were so that no one could say that they were surprised. I would also make it clear to Nancy Rae that I knew exactly what she was doing and why she was doing it and that it was unacceptable. When we choose what we do and say in life, we all consider (or should consider) what we want to happen in life, and I would put it plainly to Nancy Rae how she really expects others to react to her and how their reactions would change if she did things differently. Clearly, no one has ever told her that in her life before, and it was about time that she heard it from someone. I suppose we could guess that the counselors may have said something of the sort to her out of hearing of the others, but I would also say the same thing to Nancy Rae’s victims. Letting them know that I’d dealt with her adequately might head off their attempts to deal with her themselves and talking about what our behavior might lead others to do might also discourage revenge.

Also, the counselors were counting too much on the idea of friendship with Annie to get Nancy Rae to stop treating her badly, but that’s not at all the way that bullies work. One of the primary reasons why people bully is that they know that there are a lot of people who like mean humor, and they use their bullying to bond with those people, not their victims. Their friendships are formed on mutual contempt for the victim and the fun of humiliating that person. They’re getting everything they want through their bullying, so there’s no reason for them to stop until someone else gives them consequences and puts an end to their bully support network. I think that the counselors should have also talked to the people Nancy Rae was trying to bond with, explaining that they know what Nancy Rae is attempting to do and telling them that they would also be punished if they tried to help her, further cutting off one of Nancy Rae’s incentives to keep doing what she’s doing.

I’m not saying that it’s a perfect solution or that it would be guaranteed to work, just that I believe in being direct rather than letting things slide and just hoping that people will someday see the light. Sometimes, people just need to have things spelled out for them in no uncertain terms. If they chose to ignore what you say, then it’s on their own head, and they can’t say otherwise because you were clear and backed up your words exactly how you said you would. I do think that the counselors were right that, in the long term, revenge never turns out well. It often turns into a vicious cycle, as Annie later considers. However, in this case, some proper handling in the first place, with consequences as well as words, might have headed off the situation before it got that far.

We don’t know what eventually happened to Nancy Rae by the end of the story, but I’m not sure that Annie is right to think that she wronged her. In fact, she might have actually done her some good. Sometimes, seeing others react badly to bad treatment can make a difference to someone’s future. In my experience, people sometimes don’t realize that they’ve pushed another person too far until that other person finally reacts and says or does something. Realizing that they’ve pushed someone too far can give them a reason to change because they realize that people won’t put up with their behavior forever. Part of me thinks that maybe, at some point in the future, Nancy Rae might look back on this experience and quietly admit to herself that she had provoked it, being more careful the next time not to pick fights because she can be humiliated or excluded when people get fed up. It might even help Nancy Rae to realize that she doesn’t have to put up with her father’s ill treatment forever because she also has the right to lose patience with bad treatment, too. At least, I hope that this was a learning experience for her.

Annie realizes that both her parents and Nancy Rae are angry and hateful because of what they’ve suffered in their lives, but the problem is that both of them are taking it out on the wrong people. Annie’s parents, at least, seem to realize that what they did was going too far and taking out their feelings on someone who didn’t deserve it. By the time that Annie arrives home, they are also ready to make their peace with her and even support her return to the camp as a junior counselor, if that’s what she really wants to do.

The final days of World War II frame this story, beginning with the reports of Hitler’s death in the late spring of 1945 and ending with the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Japanese surrender in August. With the end of the war comes a new chapter in the lives of the Platt family. They’ve been through a lot together, but in spite of the girls growing up, moving out, and arguing with their parents, they still are a family. There are no more books in the series, but Annie explains that Lisa gives up the dream she once had of being a dancer because she doesn’t think that she’s star material and because she decides that what she really wants is to get married and have children of her own. In the end, she and her boyfriend get married, and she is happy with her life. Similarly, Ruth, who is now a nurse, meets a new love when she visits Annie at camp and later marries him. Annie realizes that she has found what she loves most in teaching young children, taking care of animals, and writing, and these things will form the basis of what she does with her future life.

The Best School Year Every by Barbara Robinson, 1994.

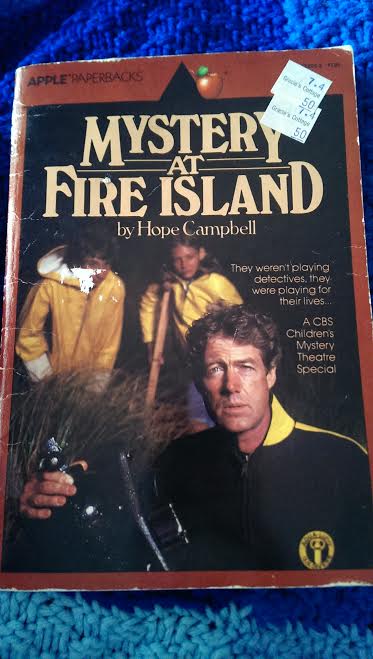

The Best School Year Every by Barbara Robinson, 1994. The Mystery at Fire Island by Hope Campbell, 1978.

The Mystery at Fire Island by Hope Campbell, 1978.