If Your Name Was Changed at Ellis Island by Ellen Levine, 1993.

Like other books in this series, this book explains about a part of American history using a series of questions and answers. Each section of the book starts with a different question about what it was like to come to America as an immigrant in the past and what happened when they reached Ellis Island, one of the main ports of entry into the United States around the turn of the 20th century, just off the coast of New York City, such as, “Would everyone in your family come together?”, “What did people bring with them?”, and “What did the legal inspectors do?” Then, the book answers each of the questions.

The questions and answers start by describing what the journey to America was like from the late 1800s through the early 1900s. Typically, families would come to the United States in stages: the father of a family (or perhaps one of the older children) would make the trip first, find a job in the United States and start saving money to prepare for rest of the family to come. Depending on the family’s individual circumstances, it might be years before all the members completed the immigration process and reunited in America.

People traveled by ship in those days, and an often-forgotten part of their journey was even reaching the port the ship to America would be leaving from. Depending on the starting point of the journey and the travel arrangements each family was able to make, getting to the port might involve crossing borders between other countries, adding another layer of legal difficulties to the journey.

There was also the knowledge that they might be turned away once they arrived at Ellis Island. One of the chief concerns at the time was illness. The inspectors at Ellis Island checked immigrants for signs of infectious diseases, and the ship companies knew that if their passengers were turned away because of the fear of disease, they would be required to pay for the return voyage themselves. To help ensure that their passengers would not arrive with a disease, they would conduct their own health checks before the ship ever left port, looking for signs of illness, giving the passengers vaccines, and disinfecting things. They were particularly afraid of passengers with lice because lice can spread typhus, which is deadly. They would often cut the passengers’ hair or comb it very carefully.

The treatment passengers on ships received depended largely on their class of passage. First and second-class passengers received the best rooms and the best food, and when they arrived in New York (assuming that was their destination), they didn’t even have to go to Ellis Island at all; the immigration inspectors would inspect first and second-class passengers on board the ship. Only steerage passengers (“third class”, the cheapest possible method of travel, used by the poorest people, the largest group) would have to get off the ship for processing at Ellis Island.

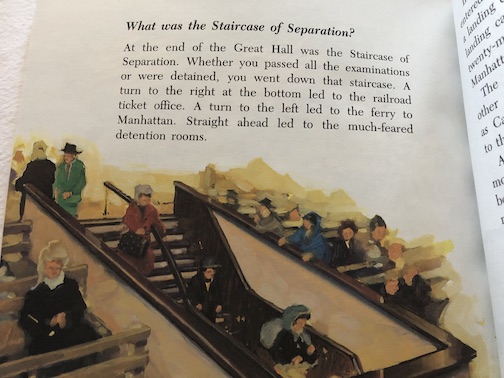

The processing center at Ellis Island wasn’t just a building; it was an entire complex. The Great Hall alone was large enough to contain hundreds of people at a time, and when it was full of immigrants there were so many languages being spoken at once (sometimes as many as 30 different languages) that some people described it as sounding like the Tower of Babel. There were also dormitories that could house more than a thousand people, a hospital for the sick, a post office, banks where people could change their cash for American money, a restaurant to feed everyone (with two kitchens, one kosher and one regular), a railroad ticket office where immigrants who would be moving on from New York could make their travel arrangements, and much more. Some people called Ellis Island the “Island of Tears” because the arrival there after a long journey was an emotional experience and many immigrants were worried that they might be sent back if they couldn’t answer the inspectors’ questions to their satisfaction. At the end of the Great Hall, there was a large staircase that came to be known as the Staircase of Separation. Everyone had to go down this staircase after their examination by the inspectors. At the bottom, they would go their separate ways, depending on their travel plans or whether they had passed inspection. People who turned to the right were heading to the railroad ticket office. People turning to the left were heading to the Manhattan ferry. People who went straight were heading to the detention rooms because they hadn’t passed the inspection.

As I mentioned before, the inspectors were very concerned about people who showed signs of serious diseases. One of the first things that would happen during inspection was a brief examination by the Ellis Island doctors. Because of the massive amount of people who had to be processed, this examination lasted only a few minutes, during which the doctor would quickly check for very specific symptoms and signs of possible illness. If they didn’t see anything obviously wrong, such as red eyes (possible sign of eye infection, although for some, it was just because they’d been crying), difficulty in breathing, or lice, they would let the people pass. If the doctors thought that they saw something that might be sign of illness, they would write a letter in chalk on the person’s clothes and send them on to be examined more thoroughly by another doctor. Getting one of these letters didn’t always mean rejection. If the other doctor decided that the first doctor was mistaken or that the person’s symptoms weren’t serious, they would still be allowed into the country. Sometimes, if a person was ill but had a curable disease, they would be kept in the hospital on Ellis Island until they were better. If the doctors weren’t quite sure if a person was ill or not, they might keep the person in the dormitories for a few days and then check them again after they had a chance to rest. The people who were sent back on the ship were ones who had diseases that were incurable or seriously contagious. (It sounds heartless, but they were trying to head off deadly epidemics. During the 1800s, large cities like New York sometimes suffered serious epidemics of deadly diseases because of the sudden influx of new people who were living in overly-crowded conditions with relatively poor sanitation. By preventing people with signs of serious diseases from joining the rest of the population, they were hoping to head off new epidemics and save lives.)

One of the more controversial parts of the examination was when they tested people for possible mental problems. They wanted to make sure that they were mentally fit enough to find work, but the problem was that the tests designed by people who didn’t take cultural differences into account when they designed them. The parts where they asked people to do simple arithmetic problems or to demonstrate that they could read, count backwards, or match up sets of similar drawings were pretty straight-forward. However, sometimes they were shown a picture and asked to describe what was happening in the picture, and the immigrants gave the inspectors some surprising interpretations because it turns out that some experiences aren’t quite as universal as some people think. For example, one picture was of some children digging a hole with a dead rabbit lying nearby. It was supposed to depict children burying a dead pet. But, some people view rabbits more as food than pets, and some immigrants said that the children were doing their chores because why shouldn’t the children work in the garden (the digging) after hunting a rabbit for dinner? Fiorello La Guardia, himself from an immigrant family, an interpreter on Ellis Island and later, mayor of New York, particularly despised tests like these because the people who designed them and administered them were trying to test the minds of others without any real idea about what their lives had been like or how their minds actually worked.

The inspectors’ examinations in general weren’t always reliable because they were often hurried (dealing with so many people in a limited amount of time) and because the interpreters weren’t always accurate, which brings us to the question of why people’s names were sometimes changed at Ellis Island. Sometimes, it was intentional. Some immigrants thought that they would be more likely to be accepted by the inspectors if they had short, easy-to-pronounce names, so they would purposely give them shorter versions of their names. There was some basis for this belief because, if an inspector didn’t understand a long, unfamiliar name, they wouldn’t have much time to figure it out and so would either take their best guess at the what the name should be, shorten it when they wrote it down, or give up altogether and write a much shorter name instead. For example, when they processed Jewish people from Russia, the inspectors often ran into difficulties in understanding their last names and would sometimes just write down “Cohen” or “Levine”, no matter what the original name really was. Sometimes, name changes were just an honest mistake because the inspector didn’t know how a name was really spelled (I can speak from personal experience because my family’s last name wasn’t always spelled like it is now, and when they found out that it had been changed, it was just too much trouble to fix it) or because they had misinterpreted something that the immigrant said. One of my favorite examples of this was a young man who tried to explain to the inspector that he was an orphan (“yosem” in Yiddish). The inspector dutifully wrote his last name as Josem.

The pictures in the book are paintings based on original photographs of immigrants and Ellis Island. (See Immigrant Kids to compare some of the pictures.)

The book also contains some further information about the lives of immigrants once they arrived in America (Immigrant Kids goes into a lot more detail), the attitudes of Americans toward immigrants at the time (varied but with strong strains of anti-Catholic, anti-Irish, and general anti-immigrant attitudes during the 1800s), and the contributions of immigrants to American society. I actually bought this book as a souvenir on a visit to Ellis Island years ago.

The book is currently available online through Internet Archive.