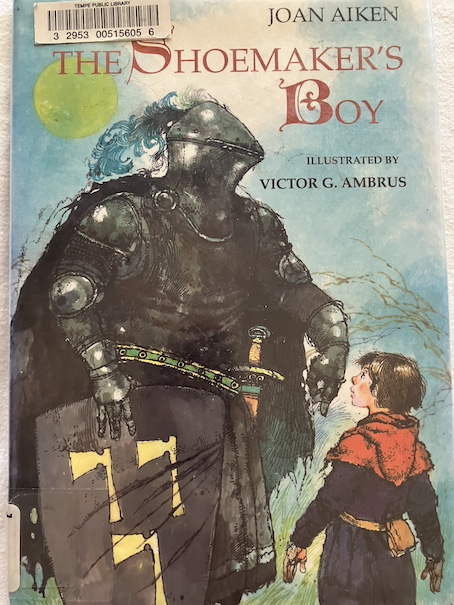

The Shoemaker’s Boy by Joan Aiken, illustrated by Victor G. Ambrus, 1991, 1994.

Jem’s father is a shoemaker, and Jem is learning his trade. However, things take a bad turn when his mother suddenly becomes ill. It’s a strange kind of illness. She sleeps all the time, can’t eat, and is hardly breathing. The doctors can’t seem to help her, so Jem’s father decides to go on a pilgrimmage to St. James in Spain and pray for his wife to get better.

While he’s gone, Jem has to mind the family business and look after his mother. Jem’s father has a reputation as a incredible shoemaker, with people coming to see him even from other kingdoms, and Jem is worried that he won’t be able to maintain the business on his own because he’s still learning the trade. However, since nothing else seems to help his mother, it seems like his father’s holy pilgrimage is their last hope.

While his father is away, Jem tries his best, but he finds it difficult to keep up with the orders that come in for shoes. He falls behind on his work, and money is running short. Then, one day, he has a strange encounter with three little men, who are only the size of young children. They are all dressed in green, and they ask Jem for the three silver keys. Jem doesn’t know what they’re talking about, but the men say that they were sent to ask him for them because someone was supposed to leave the keys with him. Jem says that nobody has left any keys with him, and suddenly, the little men vanish! At first, Jem thinks that maybe he imagined the whole thing, but this is just the beginning of a series of strange happenings.

Late that night, there is a knock on the door, and when Jem answers it, he is confronted by a knight wearing black. The knight says that he wants Jem to make him a pair of boots because he’s heard that the boots from this shop are the best. Jem doesn’t want the knight to be disappointed, so he explains to him about his father being away and that he is not as good as his father at making boots. The knight appreciates his honesty and says that he will try Jem’s work anyway. He promises Jem an excellent fee for his services if the boots are ready by morning, and to Jem’s surprise, he also asks Jem if someone has left three silver keys for him. Jem tells him that nobody has left any keys with him, and the knight says that someone may leave them by the time the boots are ready, and he asks Jem to take good care of them.

Jem works on the boots through the night, and he’s making good progress when, in the middle of the night, a second knight arrives. The second knight is dressed in white. This knight doesn’t want any boots or shoes. Instead, he asks Jem to take care of a little packet for him while he runs an errand. He says that he has heard that Jem is very trustworthy, and he says that if he doesn’t return by morning, Jem can keep the packet. Jem agrees that he will take care of the packet and make sure no one else touches it.

The rest of the night is very strange. While Jem works hard on finishing the last boot, he hears strange sounds outside, and he thinks that he can hear the little men and the black knight calling out for the mysterious keys. What does it all mean? Are the keys in the packet left by the white knight, and if so, what are they for?

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive (multiple copies).

My Reaction

This is a short, easy beginning chapter book, and it’s a nice story with a Medieval setting, written in the style of an old fairy tale. The story leaves a few questions unanswered at the end. We never really find out who the two knights are or who the little men are, although there are implications that they are supernatural. I think that they also have religious significance, tying them to Jem’s father’s pilgrimage. The contents of the white knight’s packet are not obvious, but it is the solution to Jem’s main problem. When Jem’s father returns home, he also has some information about Jem’s mysterious visitors, although he doesn’t have all the answers, either. Readers know enough at the end to appreciate that Jem made the right decision when he handled the packet and that his experiences were partly a test of his character.

The book mentions Jem’s father putting a scallop shell on his cap when he’s about to begin his pilgrimage. The scallop shell is a symbol of St. James, one of the original Twelve Apostles. The place where Jem’s father was going on his pilgrimage, the shrine of St. James at Santiago de Compostela in Spain is a real place that has been a popular site of religious pilgrimages for centuries. After Jesus was crucified, His disciples traveled to other places to spread the word about Jesus and gain new converts to the new religion of Christianity. St. James went to what is now Spain, and after teaching there, he eventually returned to Jerusalem. It isn’t entirely clear what happened to his body after he died, but one of the stories is that his followers brought his body back to Spain and buried it at the site now known as Santiago de Compostela. St. James is now the patron saint of Spain, and pilgrims who visit Santiago de Compostela often collect a scallop shell as a souvenir of their journey. Actually, that is the one complaint that I have about this book. In the story, Jem’s father puts on a scallop shell as he begins his journey, but in real life, Medieval pilgrims usually used the shell as a sign of completion of their journey.