American Girls

Samantha Learns a Lesson by Susan S. Adler, 1986.

This is part of the Samantha, An American Girl series.

Samantha attends Miss Crampton’s Academy for Girls in Mount Bedford. She is doing well and has some friends at school, but she misses her friend Nellie. She knows how poor Nellie’s family is and worries about how they are doing.

One day, Samantha comes home from school to a surprise: Nellie has returned to town with her family. Samantha’s grandmother recommended Nellie’s family to a friend, Mrs. Van Sicklen, who has hired Nellie’s father as a driver and Nellie’s mother as a maid. Nellie and her sisters will also be helping with household chores. They will also get the chance to go to school, although they will be attending public school and not the private school that Samantha attends.

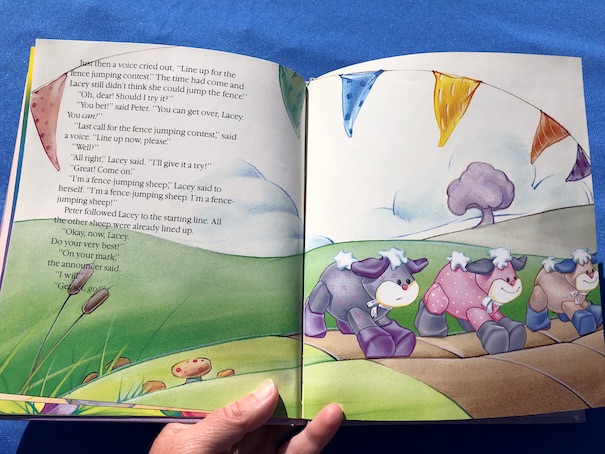

When they begin attending school, Nellie’s younger sisters do fine in the first grade, where they are expected to be beginners, but Nellie herself has trouble in the second grade. Nellie is a little old for second grade, so the other children make fun of her for being there, and she is so nervous that she makes embarrassing mistakes in front of her teacher and the other students. Nellie thinks that perhaps she’s too old to start going to school, but Samantha realizes that what she needs is a little extra help.

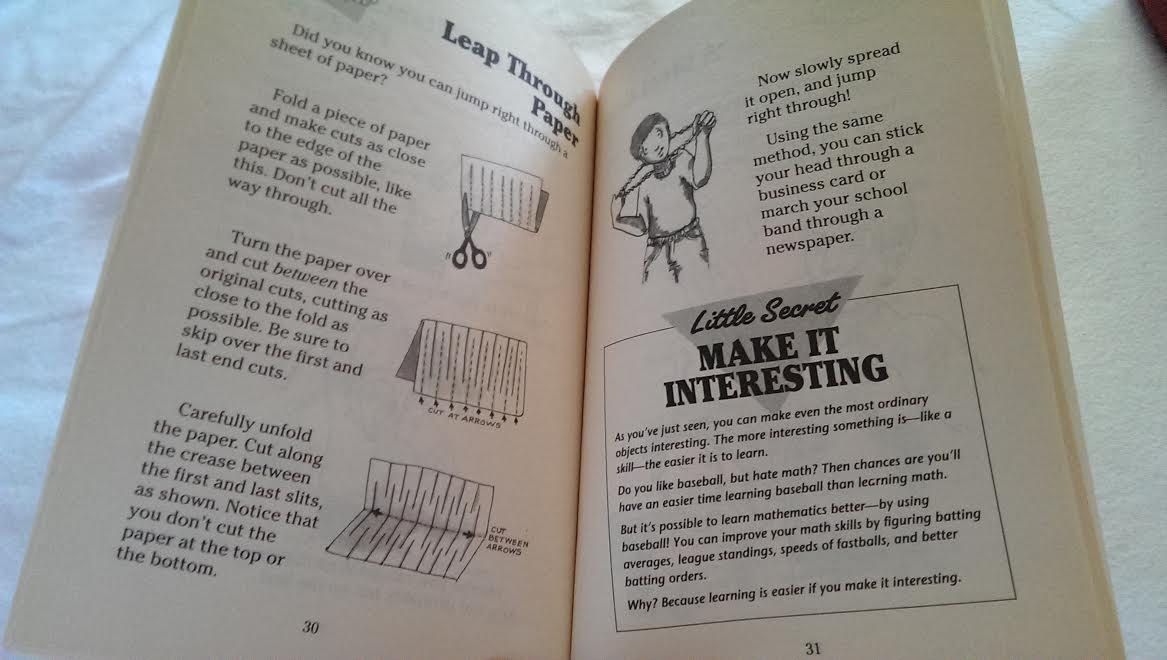

Samantha talks to her own teacher and explains the situation. She says that she would like to help teach Nellie what she needs to know, but she is not sure what Nellie needs to know in order to pass the second grade. Samantha’s teacher, Miss Stevens, thinks that it is nice that Samantha wants to help Nellie and gives her a set of second grade readers to study with pages marked for assignments. Samantha tells her grandmother what she is planning to do, and she says that it is fine, as long as the extra tutoring doesn’t interfere with Nellie’s house work too much.

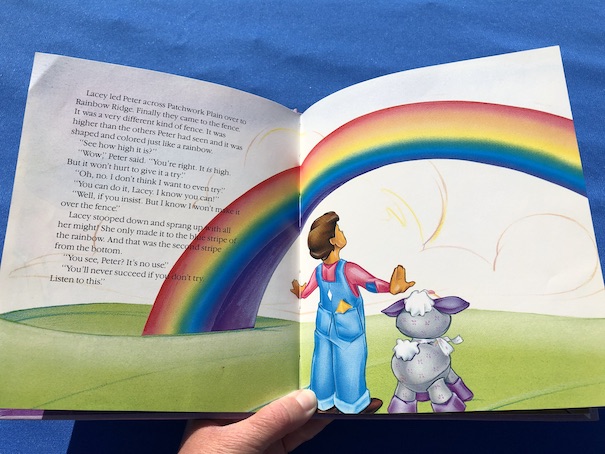

Nellie accepts Samantha’s help at their secret, private “school” that Samantha calls “Mount Better School.” During their lessons, Samantha discovers that Nellie is very good at math because she used to have to help her mother with shopping and had to keep track of her money. Nellie cannot always come for lessons because of her work, but Samantha’s tutoring helps her to improve.

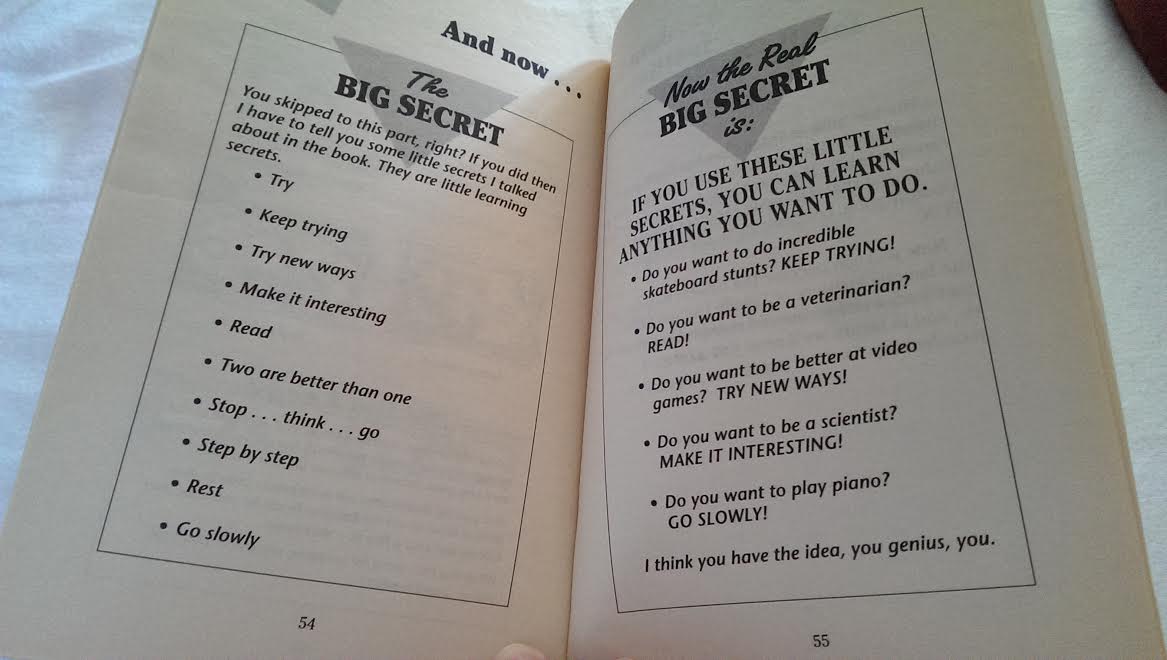

One day, when Samantha is walking home from school with Nellie and her sisters, a mean girl from Samantha’s school, Edith, sees them and criticizes Samantha for spending time with servants. She says that her mother would never allow her to play with servants. Samantha asks her grandmother what Edith means, and her grandmother says that Edith is a young lady. When Samantha asks why she is allowed to play with Nellie, her grandmother says that they are not really playing, that Samantha is helping Nellie, which makes it different. That explanation doesn’t entirely satisfy Samantha.

However, her grandmother is both understanding of the help that Samantha has been giving to Nellie and serious about the need to help others. When Edith’s mother and other ladies of the neighborhood come to visit and complain about Nellie’s family and how Samantha is spending time with them, Samantha’s grandmother defends them and says that Samantha is doing good.

Meanwhile, Samantha’s school is preparing for a public speaking contest with the theme “Progress in America.” To prepare for her speech, Samantha asks her grandmother, her Uncle Gard, and other people what they think about progress and what the best inventions are. They mention inventions like the telephone, electric lights, automobiles, and factories. Samantha is fascinated by the idea of factories and the variety of products that they can make. However, when Samantha reads her speech to Nellie, Nellie is not nearly so enthusiastic about factories as a sign of progress. Nellie used to work in a factory herself, and she knows that they are not pleasant places. She tells Samantha how factories are noisy and how dangerous the machines are for the workers. The factory workers are also very poorly paid, which is why the products they make are so cheap.

Nellie’s stories about factories bother Samantha. When it is time for the public speaking contest, Samantha delivers a changed version of her speech in which she discusses the dangers of child labor and how some form of progress, particularly ones that endanger children, are not good forms of progress. Samantha’s thoughtful speech wins the contest, and her grandmother understands that Samantha has been learning things from Nellie even while teaching her.

In the back of the book, there is a section with historical information about education and child labor during the early 1900s.

The book is currently available to borrow for free online through Internet Archive.

#1 The Beast in Ms. Rooney’s Room by Patricia Reilly Giff, 1984.

#1 The Beast in Ms. Rooney’s Room by Patricia Reilly Giff, 1984. However, even though he’s embarrassed at having to attend special reading classes with Mrs. Paris while most of the rest of his class has normal reading, these special classes really help him, not just to improve his reading skills, but to connect with other kids in his new class who have the same reading difficulties he does and who understand how he feels.

However, even though he’s embarrassed at having to attend special reading classes with Mrs. Paris while most of the rest of his class has normal reading, these special classes really help him, not just to improve his reading skills, but to connect with other kids in his new class who have the same reading difficulties he does and who understand how he feels. Going to School in 1776 by John J. Loeper, 1973.

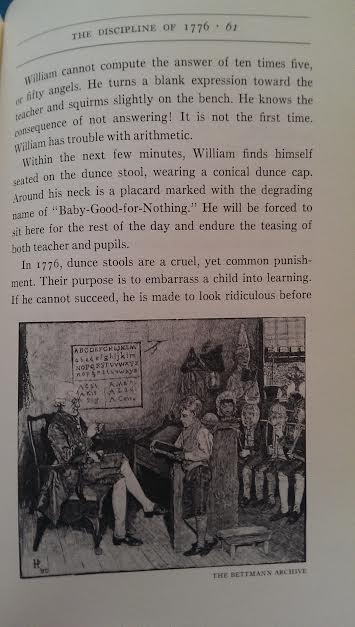

Going to School in 1776 by John J. Loeper, 1973. These explanations are told in story form, rather than simply explaining listing the ways children could live, learn, and go to school, trying to help readers see their lives through the eyes of the children themselves. The children’s lives are affected by the war around them. As the book says, many town schools in New England were closed during the war, so the students would attend “dame schools” instead. A dame school was a series of lessons taught in private homes by older women in the community. In other places, such as cities like Philadelphia, official schools were still open. Discipline was often strict, and school hours could be much longer than those in modern schools. Sometimes, children would argue with each other over their parents’ positions on the war.

These explanations are told in story form, rather than simply explaining listing the ways children could live, learn, and go to school, trying to help readers see their lives through the eyes of the children themselves. The children’s lives are affected by the war around them. As the book says, many town schools in New England were closed during the war, so the students would attend “dame schools” instead. A dame school was a series of lessons taught in private homes by older women in the community. In other places, such as cities like Philadelphia, official schools were still open. Discipline was often strict, and school hours could be much longer than those in modern schools. Sometimes, children would argue with each other over their parents’ positions on the war. There were different standards for what girls and boys were expected to learn because their learning was guided by what they were each expected to do with their adult lives. A typical school might teach boys subjects like, “writing, arithmetick [sic], accounting, navigation, algebra, and Latine.” Generally, “reading, writing, arithmetic, and religion” were common elementary school subjects. Latin lessons and other advanced subjects were typically for boys who planned to become lawyers or clergymen. Girls were likely to receive little formal education beyond reading and writing, and black people were less likely to receive even that.

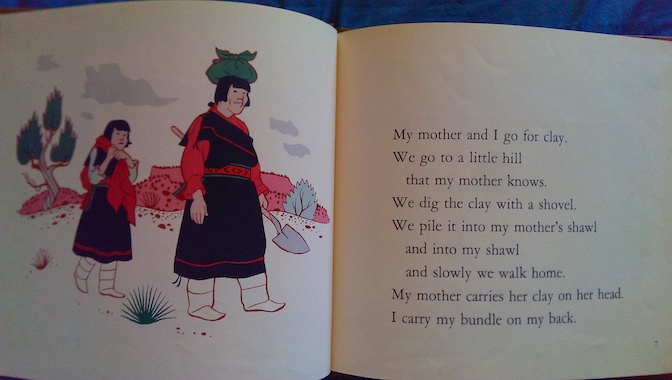

There were different standards for what girls and boys were expected to learn because their learning was guided by what they were each expected to do with their adult lives. A typical school might teach boys subjects like, “writing, arithmetick [sic], accounting, navigation, algebra, and Latine.” Generally, “reading, writing, arithmetic, and religion” were common elementary school subjects. Latin lessons and other advanced subjects were typically for boys who planned to become lawyers or clergymen. Girls were likely to receive little formal education beyond reading and writing, and black people were less likely to receive even that.