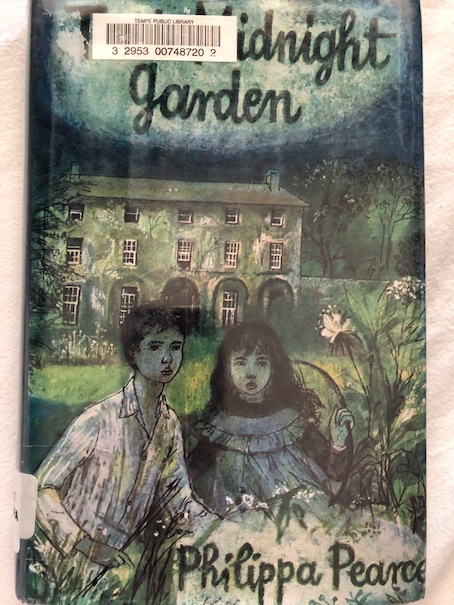

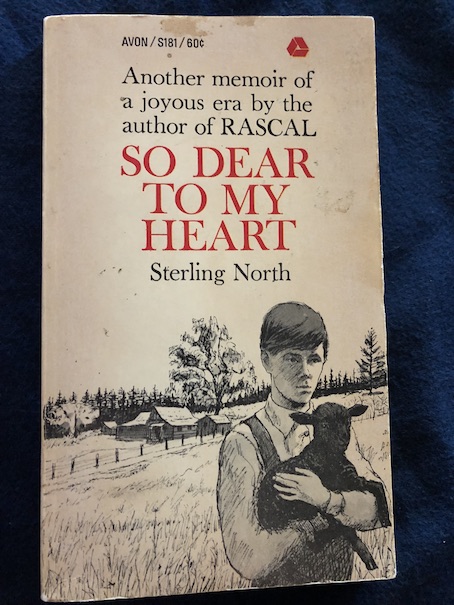

So Dear to My Heart by Sterling North, 1947.

The original form of this story was actually from 1943, when the book was called Midnight and Jeremiah. In that book, the black lamb was named Midnight, not Danny, and many of the subplots that came to dominate this edition of the book didn’t exist. This edition of the book was rewritten and published after the Disney movie of of the story, which is why it was given the same name. The Disney movie was half live-action and half animated, and it made some changes to the story that were reflected in this rewrite/reprint. Naming the lamb “Danny” after the race horse Dan Patch was Disney’s idea. I actually think that I would have liked the original book better because I didn’t like the way some of the characters were portrayed in this book.

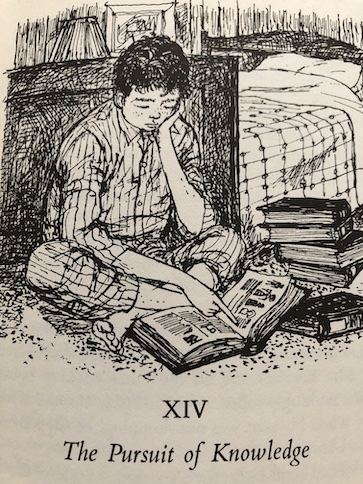

I have to admit that I was really frustrated with one of the characters in the story, and because of that, I found it difficult to wade through the parts dealing with her. However, it is important to actually finish this story once you begin because, otherwise, you won’t get the full picture of the story. It’s not that the ending is particularly surprising, and I can’t say that I ever really became fond of the character I didn’t like, but the more you pay attention to how the story gets to the ending, the more you realize what the one of the points of this story really is. This story is about the love between a boy and an animal. It has Christian themes and themes about hatred, prejudice, and loss. However, what struck me the most in the end is that this is also a story about knowledge and perspective. Knowledge and being open to knowledge can change a person’s perspective, but also having a different perspective in the first place can give a person knowledge or leave them more open to gaining it.

I’ll warn you that this is going to be a rather long review, and parts are going to seem a little repetitive because the way my review is organized is based somewhat on the way this book was organized, giving bits and piece of information about the same underlying situation accompanied by reactions to it. At the end, I’ve also included some odd historical information that relates to things mentioned in the story.

Jeremiah Kincaid, called Jerry, lives with his grandmother on the Kincaid family farm in Cat Hallow outside of the small town of Fulton Corners, Indiana in 1903. His parents are dead, having died in a fire when he was young. The full circumstances behind their deaths are not explained until the end of the book, and there are a few things in the book about their deaths and some current happenings that seem a bit mysterious. This book is not really a mystery story, but in way, parts of it play out a little like a mystery because there are missing pieces of information that need to be filled in before you really understand what’s going on. Knowing exactly what happened to Jerry’s parents and why eventually helps Jerry and his grandmother to resolve some of their feelings about their deaths and their relationship with each other. For most of the book, Granny Kincaid thinks she knows what happened, but it doesn’t take long for readers to realize that she’s unreliable as a narrator. Jerry’s Granny Kincaid is a very strict and strongly religious woman, and she is the character I did not like, who almost discouraged me from finishing the book. It wasn’t being strict and religious that made me not like her. I wouldn’t have minded that so much by itself; it’s the rest of the story of what she is that got to me. In a way, that feeling of not wanting to look further also plays into the story and the desire of whether or not you want to know more about what is behind a bad situation. In an odd way, Granny actually did remind me of something, but I’d like to save what she reminded me of until near the end because it will make more sense then.

When the book begins, Jerry is angry with Granny for selling his beloved bull calf to a butcher. Jerry loved the calf because he had raised it himself, but to Granny, it was just part of the routine of farm work. To Granny, animals are meant for food unless they are specifically work animals. Jerry feels more of a personal connection to the animals, which is also important to the story. Jeremiah longs for an animal that he can actually keep and love. This is what guides Jerry throughout the story.

Jerry gets his chance of an animal to love when the new lambs are born and one of them is a black lamb, rejected by its mother. Granny would be content to let the little black lamb die, thinking of it as an evil omen. Her casual cruelty and callous attitude when Jerry points out that it’s just an innocent lamb who couldn’t help being born black and is scared and hungry and will surely die without care were, frankly, pretty disgusting from my perspective. Granny is very religious but without compassion or empathy. For her, animals are to be used, and whatever or whoever is meant to die isn’t something she’s going to bother herself about. Not only that, but part of her callous, unfeeling nature is based on bitterness toward events in her own past, which are clarified through the story. There is/was a bitter history between the Kincaids and the Tarletons, who owned the next farm over, and Granny knows that the little lamb was sired by the Tarletons’ old black ram. Even though I didn’t like Granny, I kept reading because the most compelling part of the book is learning the full history of the Tarletons and the Kincaids, which comes out bit by bit as the book goes on. The way that this knowledge of the family’s history is given to the readers, piece by piece, is important. Each time that Jerry learns a little more about his family’s history, the story changes a little, giving not only Jerry, but the readers, a slightly different impression of what happened and why.

To help explain it, I’ll give you a kind of summary of what Jerry learns in the first chapters of the book. In her youth, Granny Samantha Kincaid married David Kincaid, Jerry’s grandfather, who is now deceased. David’s rival for her affection was Josiah Tarleton. Before Samantha and David were married, the two men had a terrible fight over her which had left David the victor but permanently injured. Following the marriage of the Kincaids, Josiah settled on a farm near theirs. Over the years, the Kincaids experienced hardships of various kinds, while Josiah became a wealthier man and flaunted that wealth at the Kincaids to show Samantha what she had missed by not marrying him. Even after Josiah married a woman named Lilith, things were still bitter between the two families. Samantha became convinced that Lilith was a witch who cursed their sheep with illness, although David said that was only superstition. Although Lilith is now dead (as are Josiah and David), Samantha is still afraid of anything associated with the Tarletons, thinking of it as evil. That is Granny Samantha’s frame of mind, as it has been for years, and that is the basic reason why she regards the black lamb as evil, because of its association with the Tarletons. As far as the beginnings of the bitter Kincaid/Tarleton feud goes, it’s an accurate description of the situation. From this basic description, it sounds like the Tarletons were mean, greedy, and vindictive, lording their better fortune over the Kincaids and maybe even doing things to make life harder on them. However, that is not the entire story. That description barely scratches the surface of the real situation.

Granny is a callous person with some vindictiveness of her own. Jerry himself has been on the receiving end of Granny’s callousness, and the story mentions that his birth was “unwanted,” like the lamb’s, something that he senses from his grandmother (a major reason why I didn’t like her). Part of the reason why Jerry craves love in his life and shows it to the animals is because he doesn’t get it from family, what’s left of it. Jerry insists on taking care of the little unwanted lamb, naming him Danny. He persuades his grandmother that the lamb will give good wool. As the lamb grows and gets into trouble, Granny says that it’s proof that she was right to think of the lamb as evil. However, Jerry defends the lamb, saying that Danny is just an animal that doesn’t know what it’s doing and forbidding his grandmother to turn Danny into food, a sentiment echoed by Uncle Hiram.

“Uncle” Hiram Douglas is the local blacksmith, a family friend, not related by blood to anyone else in the story, although he acts as a father to Jerry, having no children of his own. Uncle Hiram knew both the Kincaid and Tarleton families for years, observing their feud from a different, more distant perspective, and his account of what happened is more reliable than Granny’s. He was careful not to involve himself directly in the families’ troubles because their situation was toxic, and he knew it. Early in the story, Uncle Hiram sees the parallels between Jerry and his lamb, both of which have been deprived of love and proper care through no fault of their own. He tells Jerry that both of them are from good stock and not to pay attention to the superstitious nonsense that Granny tells him. It is Uncle Hiram who suggests to Jerry that he should take Danny to the County Fair when he’s bigger and show him off because Danny has the potential to be a champion. Jerry seizes on the idea, and it gives him hope. For much of the story, saving his lamb from Granny and taking Danny to the fair are his main goals.

It is Uncle Hiram who tells Jerry more about his grandmother’s long-standing feud with Lilith Tarleton and how she blamed Lilith for an unexpected flood that almost drowned his grandfather and killed some of their sheep (one of many unrelated things that Samantha blamed on Lilith). Samantha had been so sure that Lilith was a witch and caused the disaster with a curse that she actually hid in a place where she knew Lilith would go and waited for her to come along so that she could throw rocks at her, stoning her as a “witch”, and this incident is generally known in the community. Josiah Tarleton may not have been a nice person, but for all of her Bible-quoting, Granny Samantha has a fierce temper and an unpredictable nature. The picture of what happened between the Tarletons and the Kincaids changes a bit with the added information of Samantha’s sneak attack on Lilith.

The book continues like that, shifting back and forth between things happening in the present and Hiram’s explanations of the past. As the descriptions of the past become more detailed, Granny’s views are increasingly shown to be wrong, and her behavior more erratic and hateful. I did not find Granny a likeable or sympathetic character, to say the least. She struck me immediately as callous and unhinged, and that image stayed with me throughout the story. She is unfair and has double standards for how she views the world and human behavior. When misfortune happens to someone else, like an innocent black lamb (as well as other people, as described later in the story), Granny says it’s just the will of God and she doesn’t care, but if misfortune happens to her, it’s evil black magic and she’ll stone the first person she doesn’t like as the one responsible for it. This is how her mind works. When Jerry interacts with the people of the nearby town, readers discover that Granny is hardly seen as a pillar of the community. In fact, she hardly interacts with the community at all. Even the men down at the general store joke about Granny Kincaid being a witch herself. Jerry hears them joking, and it leads him to talk to Hiram more about his family.

When Uncle Hiram explains about the jokes the men make that both of Jerry’s grannies were possibly witches, more of the conflict between the Kincaids and the Tarletons is revealed. Samantha Kincaid doesn’t like to talk about Jerry’s father, who is her dead son, or his wife and is often deliberately callous with Jerry because Jerry’s mother was actually Arabella Tarleton, Lilith’s daughter. Up until this point in the story, Jerry was completely unaware of this or the fact that Lilith was his grandmother, too. Now, Jerry knows that Samantha’s son, Seth, married Arabella, and both of them died in a fire, something which Samantha blames on Arabella. With this information, the story shifts again, looking a little like a Romeo and Juliet type of situation.

Uncle Hiram doesn’t believe in witches at all, and he explains the truth about his grandmothers to Jerry. He says that, whatever Granny Kincaid says, Lilith was never an evil person, and he doesn’t really think that Granny Kincaid is, either. I’m still a little less charitable toward Granny here. Granny’s behavior and attitudes show a definite sadistic streak. I’m not talking about the way she sees animals mainly as food because that’s just a natural side of farming. Samantha is a vindictive person, with an inability to put blame where blame is due, choosing instead to take it out on an innocent victim, possibly because the innocent victim is more vulnerable to attack or because she can’t handle the thought of what or who is really at fault for a situation. In her attacks, she frequently resorts to physical violence, even inflicting harsh physical punishment on Jerry and also some twisted psychology, when you consider some of the things that Granny says to him.

As even more of the history of these two families comes out, you learn that there are pieces of the story that Samantha is deliberately ignoring or distorting in her accounts of what happened. First, Samantha blamed Lilith for Josiah’s jealous vindictiveness, rubbing his successes and the Kincaids’ hardships in her face because she refused his “love.” At least, he did this up until he also suffered hardships and lost much of his money later in life. This is another part of the story that is revealed later. At first, the characters make it sound like Josiah was more prosperous overall and had less hardship than the Kincaids, but it was more the case that his hardships came a little later in life, something that changes his story a bit. The reality of the situation is probably that the families were more equal in terms of their wealth and luck than earlier described. Their farms are literally right next to each other, outside of a small town where nobody is truly rich. Also, one of the misfortunes Josiah suffered was the early death of his wife. It turns out that Lilith died much earlier in life than any of the older generation of adult characters, not even living to see her own children grow up. Samantha and Lilith actually knew each other for far less time than it would sound from the way Granny talks. After Lilith’s death, Josiah seemed to kind of give up on life and generally let his children run wild because he didn’t quite know how to deal with them. In spite of Lilith’s death, Samantha continued to blame Lilith for everything that went wrong in her family’s lives. None of it was Lilith’s fault, but Samantha decided it was because she could not or would not see Josiah, or even members of her own family, for what they really were and Lilith for what she was. Lilith was a gentle soul who died relatively young, but she remained the evil witch and lurking spirit that haunted Samantha’s own troubled mind.

So, what was Lilith really like, and how do I know that she was a gentler person? Uncle Hiram explains that, unlike Granny, Lilith actually loved animals, just like Jerry does. Her father in Kentucky knew the famous Audubon who studied birds, and Lilith was also something of an amateur naturalist. People in Indiana distrusted her because she was more educated than most, and they thought it was weird that she knew all the “fancy names” for different birds and plants. Hiram understands the names that Lilith was using because he actually interacted with Lilith as a friend, and hearing her explanations broadened his experiences. The people who just thought Lilith was strange and “witchy” never figured it out. If I had to live with people like that, I’d probably be more trusting of animals than my fellow human beings, too. Hiram suspects that Josiah may have harbored feelings for Samantha even after his marriage to Lilith (the fuel for his vindictiveness, wanting to see his former love suffer for rejecting him) and that Lilith indulged her love of nature as an escape from her husband’s uncomfortable preoccupation with a woman who never returned his affections (and who lived on the next farm over and liked to call her a witch and throw stones at her like a crazy person for things she never did and possibly knew nothing about before the sneak attack – no, I just can’t let that slide – going out into nature to escape from her husband and study the plants and animals was what Lilith was doing when Samantha violently attacked her), leading to Lilith’s reputation for being a bit strange and possibly a witch.

This picture of Lilith is vastly different from the picture that Granny had given Jerry and even what other townspeople say about her, and it is much more truthful. (There is also more evidence that supports it later in the story.) Lilith was a spirited and loving young woman who defied her father to marry Josiah. She was loyal to him in spite of his obsession with Samantha, and she ran a tidy household, educating her children herself as best she could and teaching her daughter to play the violin. This was the person Granny considers to be evil, even beyond the grave, in contrast to herself.

At one of the points in the story where they discuss Seth and Arabella’s wedding, Granny says that deceased Lilith’s spirit was angry because Josiah, who was still alive at the time, kissed her hand at the wedding. Josiah was a drunkard who had taken a liberty, by Granny’s description, but poor dead Lilith was still the bad one. (Another thing we learn along the way was that Josiah’s mind deteriorated in his final years, an apparent combination of drinking and stress from the early loss of his wife and other hardships his family suffered. This comes from Hiram, not Granny, whose own mind I found suspect from the first.) Possibly, Granny could not bring herself to fully label Josiah has the bad one because he always liked her. Granny is actually somewhat vain and self-centered, and although she was not in love with Josiah and would never return Josiah’s feelings, I get the impression that she was flattered by them. That two men fought over her, even though she had a clear preference for one of them, and that one of them continued to follow her and dwell on her made her feel good, if a bit awkward that Josiah was the more prosperous of the two for a time as well as somewhat vindictive. Lilith, as Josiah’s wife, took at least some of Josiah’s attention away from Samantha when she entered the picture, and I suspect this was probably the basis for her becoming the bad one in Samantha’s mind, for representing a competitor for Josiah’s feelings, even though Samantha was married to the man of her choice and wouldn’t have wanted Josiah anyway. Sometimes, even people who do not want something in particular for themselves still feeling strangely resentful when someone else gets it, especially if the other person seems to benefit from it. Early on in their marriages, Lilith seemed to have gotten the better deal by marrying the richer man … until more of the story is told, and you find out that wasn’t quite the case. It didn’t take that long for things to turn rough for the Tarletons, and Lilith’s life didn’t have a very happy ending.

Uncle Hiram says that he has tried to explain all of this to Granny for the last 30 years, but “She don’t listen, or she don’t understand, or she don’t want to know-cain’t quite figger it out.” (This is one of those books where the author uses misspellings to convey accent.) My theory is what I said before, that Granny blames the wrong person for the source of problems and that blame is based solely on personal dislike. Lilith got the man Granny could have had, even if he was a self-centered jerk who Granny didn’t really love, and a more comfortable, prosperous life (at least, for a time, in a way, on the surface), while Granny’s husband was injured by Josiah and constantly struggled to make a living in the face of repeated misfortunes that were mostly random chance. The longer Granny harbored that irrational hate, nursed it, and indulged it, the more difficult it was to let go of it, not only because it had become habit but because of what it would mean to her personally to admit that she had done something horribly wrong. If Lilith was really her opposite in everything, and it turned out that Lilith was a really good person and a good mother, educated and nature-loving, what would that make Samantha? It would mean that she was not “on the side of the angels” and righteousness, that she was the one causing harm to the innocent rather than being the poor, injured party herself. (I still remember that Samantha is the one who hides in bushes and throws rocks at unsuspecting people, not Lilith. Once you know certain things, you can’t un-know them.) It would be a difficult thing for her to take, the realization that she might be more witch than the supposed witch and hardly an angel. As I said, people in the community have noticed it, too. Lilith may have seemed “witchy” to them because, as Hiram said, she was a little different and they didn’t really understand her, but Granny is witchy for much more obvious reasons.

At one point, Hiram tells Granny directly that she’s being unfair to Jerry and not raising him with the love he really needs, and she angrily tells him that she has to be this tough to keep Jerry from going the way of his parents, whose souls she considers sinful. During the course of the story, she actually tells Jerry that his parents are not in heaven, making up a song about them and how their marriage lead to hell. This is a terrible thing to tell a child and a twisted upbringing to give an orphan! Hiram tells Granny that, while she’s had to struggle and work hard all her life, she’s not the only one who works hard, suffers hardship, and is a good person and that the way that she’s behaving is unfair, but she only responds by both complaining and bragging at the same time about how hard she works and how often she prays and how much she’s done for Jerry, as if that entitles her to behave the way she does. Samantha is stuck on herself but can’t see it because she phrases her vanity in terms of her hard work and personal suffering, which she considers virtues, ignoring the bad behavior she has indulged in and the suffering she herself has caused. The book calls it her “proud bitterness.” (Insert wordless scream of frustration here.)

Because Jerry is Lilith’s grandson as well as hers, Granny Samantha sees evil in him, like she does in the lamb, and Jerry senses that she does not really love him. That is the strongest reason why I dislike Samantha as a character, plus her vindictiveness toward the innocent and helpless and inability to establish limits on how she indulges her vindictiveness. Although I think the author meant us to see her more as sad and warped by sadness than bad, I didn’t really see her that way myself. To me, she was irrational and possibly dangerous, given her history of physical attack, not “purely on the side of the angels” as Uncle Hiram characterizes. Seriously, hiding in the bushes to throw stones at a “witch” is not a healthy coping mechanism. The guys down at the general store know this and that is why they make witch jokes, but Granny doesn’t seem to have grasped how this looks even to people in her own town. Living alone with her grandson on their isolated farm has kept her steeping in her own bitterness and out of touch with reality. Only Uncle Hiram’s influence has allowed Jerry to get in touch with the truth of his family’s past and situation, and this is a central part of the plot.

I’m down on Granny Kincaid a lot, as you can tell by my repeated rants against her, but part of what makes characters like this so frustrating is that they are so obvious as plot devices. If Granny were a kinder, more reasonable person, this book would both be much less frustrating and much shorter. She is deliberately uncaring and unreasoning because she has to be in order to complicate the plot. She is one of the obstacles that Jerry must overcome. There’s no use arguing with Granny because she will and must remain resistant to persuasion, providing necessary plot tension, until the point in the story where the other characters either find a way to get around her or she has a change of heart and redeems herself. Given that Granny is Jerry’s grandmother and that this story has religious themes, I guessed that we would be going the redemption route eventually. However, I also knew that, with about 200 pages in the book, I’d probably have had more than enough of Granny by that point, which made me wonder if it would be worth it. I wouldn’t say that the redemption was worth it for Granny’s sake because I still didn’t really like her at the end, but by the time I got through all of the information that I’ve provided so far about the Kincaid and Tarleton families, I began to notice how the story about the families shifts slightly with each new piece of information about them, as seen from Hiram’s more neutral perspective. There is a larger point to be made here as the story continues, and Jerry learns more about the circumstances of his parents’ deaths, clearing up some additional plot holes that have been left hanging.

What’s left to tell? Notice that, while I told you that Jerry’s parents died in a fire, the Kincaid farm is obviously still standing and so is the Tarleton farm. They have not burned to the ground. So, where was this fire that killed Jerry’s parents? Also, if Josiah, Lilith, and Arabella Tarleton are all dead, who is running the Tarleton farm? Remember, Danny the lamb was sired by the Tarletons’ old black ram. Who owns that ram? Keep these points in mind for a moment.

Getting back to Jerry’s goal of taking Danny to the fair to win a prize, Granny is naturally resistant to the idea of going to the fair at all, but Hiram starts to win her over by suggesting that she show some of her weaving there (a successful appeal to her vanity), and Jerry promises to earn the money they need to go. Earning the money to go to the fair provides another obstacle for Jerry to overcome. Jerry begins hearing violin music at times, although he’s not sure where it’s coming from. He begins to think that it might be his mother’s spirit, trying to encourage him in his goals. There is also a scare when Danny is lost during a storm, and Jerry fears that he will never see him again.

The loss of Danny during a terrible storm is the turning point in the story and the real beginning of Granny’s redemption. Jerry doesn’t know whether Danny is surviving the storm or not, and Granny becomes truly worried about how upset that Jerry is and how she is unable to comfort him. She tries to tell him that whatever happens to Danny is the Lord’s will, and Jerry stuns her by saying that the Lord can’t have his lamb. Granny chastises him for blasphemy, but he refuses to take back what he says. Granny worries that Jerry might feel the wrath of God for what he says, and she actually tries to say that it’s her fault that Jerry says these things, that maybe she hasn’t raised him right, in the hope of sparing him from God’s wrath. This is the most concerned that Granny has been for Jerry since the book began. Jerry says that love isn’t evil, and for the first time, Granny admits that it isn’t, unless a person loves himself more than God. When Jerry asks how he can love a God who took away both his parents and his lamb, Granny is at a loss for an answer. She tries to explain that God is both all-merciful and all-powerful, but Jerry says that if God was really all merciful, He wouldn’t have let his parents die, and if He was all-powerful, He could have saved them. This is part of the age-old problem of why bad things happen to good people. Was there something wrong with God, perhaps even his non-existence? There are some who would argue that. Or was the fault with the people involved in the story, that their fate was punishment for their sins or brought about by their wickedness, as Granny has always believed? Granny has always believed that her son died because of his sins and that Arabella was the one who led him into sin. This belief has been the basis of all of her harshness with Jerry. However, there is another possibility, that is it all more a matter of perspective, that there is more information missing from this story which would make the situation more clear.

Granny’s inability to answer Jerry’s questions about the nature of God and prayer and why bad things happen to good people are what bring about a change in her. The older I get, the more I think that a little uncertainty in life, and even in religious faith, can be a good thing. Uncertainty is what keeps people open to knowledge because they feel like there is more that they don’t know. People who think they know everything they need to know tend to close the books because they don’t feel the need to learn more. People who are sure that they are doing everything that God wants don’t ask themselves what more they need to do, whereas people who aren’t sure are open to improvement. Some of the least confident people in life are the ones who are actually doing the most and trying the hardest because they constantly question what they’re doing, check themselves, and are the most open to learning and improvement along the way, the exact opposite of the Dunning-Kruger Effect. There have been many famous people who have experienced severe self-doubt, and sometimes, that’s what pushes people on to greatness. Even saints, viewed by others as having a special relationship with God and providing others with help and a sense of peace, often experienced their own dark times, self-doubt, and even doubt in God and their service to them. The great thing about saints isn’t that they were superior humans without flaws and human troubles but that they didn’t let those things stop them from doing the great things that they were meant to do. Perhaps the key is in seeing doubt not as defect but as a tool and uncertainty not as a failing but as a guide to learning and improvement.

Up to this point in her life, Granny Samantha felt absolutely certain about everything. She was as certain of Lilith’s wickedness as she was of her own faith in God. She had thought of all of the family’s misfortunes only in terms of what had happened to her, and now she realizes that Jerry was the one who was truly punished by the loss of his parents while being just an innocent baby, with no sins that needed to be punished. Now, Granny is confronted by the fact that she really doesn’t know everything and that some things may not actually have a definite explanation, or at least not one that is easy to find. Granny experiences doubt for the first time. It affects her so deeply that she tells Hiram that she told God that it’s about time that He answered her prayers about something or she might stop believing in the power of prayer and that He should really let Jerry find his lamb. She feels a little odd about saying this to God, even though she felt strangely better after saying it, but Hiram tells her that he doesn’t think it’s so bad. He says that he’s experienced his own doubts over the years and that he thinks that prayer is basically a way of telling God how you feel and letting him share the burden of worries. It’s natural for human beings to feel things like doubt, worry, and anger when things are going wrong and everything seems unfair. Granny admits that she has felt better since she has admitted her true feelings to God, like she truly has left the problem with Him, instead of keeping all of those negative feelings to herself, as she has for years.

Fortunately, this story does have a happy ending. Jerry does find Danny again after he is lost, and they do manage to go to the fair. Danny does not win the livestock competition because, as a black lamb, the judges decide that he is in a class by himself, but noting his quality, they give Jerry and Danny a special award for being unique. But, what’s important happens while Jerry is still searching for Danny and how he learns the final pieces of the puzzle concerning his parents’ death.

While Jerry was searching for Danny, he also met and connected with his Uncle Lafe, Arabella’s brother and Danny’s only other living relative besides Granny. Lafe is somewhat slow mentally, what the other characters call a “moonling.” He is referred to in passing a few times earlier in the story, but no one explains much about him other than his mental slowness. His slowness was considered one of the misfortunes of the Tarleton family because it caused his parents some worry. Even though Lafe is still living on the Tarleton farm next door and is the owner of the black ram, Jerry has not seen or spoken to him up to this point. However, like Arabella before him, Lafe knows how to play the violin and has kept the violin that once belonged to his sister. Jerry had heard him playing at other times earlier in the story, taking comfort in the playing and believing that it was his mother’s presence, trying to communicate with him. Lafe doesn’t talk much, and although he can read and write a little, he’s not very good. He shows Jerry Lilith’s old collection of books, showing that she was an educated woman, as Hiram said. Lafe cannot read well enough to read all of the books, and Jerry admits that he can’t read that well yet, either. Lafe also shows Jerry where he recorded Jerry’s birth in their old family Bible, a common practice in old times, before modern birth certificates. Jerry realizes that, in spite of the rift between the Tarletons and the Kincaids and the fact that Jerry has never really met his uncle before, his uncle has always accepted him as a full member of his family, giving Jerry an unexpected feeling of belonging.

Before the story is over, Uncle Hiram tells Jerry the final truth about his parents’ deaths. Both Seth and Arabella were fed up with life in Cat Hollow. They were tired of their parents’ feud and the limited opportunities for life there. Arabella loved horses and had real skill with them, so they took a horse with racing potential and tried to start a life in horse racing in Kentucky, where Arabella’s grandfather lived, where both of their families had lived before coming to Indiana. Their involvement in horse racing and gambling was what made Granny decide that they were sinful people. They later died in a burning stable in Kentucky. Granny told Jerry that she believed that Arabella had sent Seth into the burning stable to kill him on purpose, using their race horse as an excuse. She said that they had been living apart before that and that Arabella probably just wanted to get rid of Seth. When Jerry asked her how Arabella managed to die in the fire as well, Granny says that she could never figure it out.

This final piece of the puzzle is solved when the man who managed Arabella’s grandfather’s horses explains the night of the fire to Granny and Jerry. Seth had temporarily gone to Chicago to find a job to support his wife and child, but he had returned to where Arabella was staying with her grandfather to visit her. The fire broke out at night, and when Seth realized that his wife’s beloved horse was in danger, he insisted on going into the barn to try to save it. Arabella actually tried to stop him, but he ran in anyway. Arabella ran into the barn after him to try to save him, and they were both killed. After her earlier humbling at Jerry’s unanswerable questions, admitting her true emotions about the family’s misfortunes, and the victories of both Jerry’s lamb and her quilts at the fair, Granny is finally in a state of mind where she is able to except the truth of her son’s death. It was not caused by his sinfulness, but his love and a set of unfortunate circumstances, and Arabella had tried to save him at the expense of her own life. This knowledge helps Granny to make peace with the ghosts of the past.

I do feel like Granny receives this new picture of what happened to her son with less comment and emotional release than I would have expected. For most people, this would have been a very emotional moment, perhaps with crying or a sense of guilt for having put all the blame in the wrong place for years. Granny even made a quilt depicting a demonic marriage and writing a song to sing to her grandchild about how his parents were wicked and in hell, for crying out loud! So, what does Granny actually say about this final revelation?

“Wal,” said Samantha, “it jest goes to show. Cain’t never tell about true love. Guess I’ll have to change the last few verses of my song ballad. Burned to a crisp in each other’s arms, no doubt. It’s a real sad story.”

And that’s her final word on the matter. Great. I guess it just “goes to show” why I really don’t like Granny: she doesn’t have much emotional range or empathy even after her redemption experience. All through the story, it was all about her: her husband who was hurt by the rival for her affections, her husband who was almost killed in a flood, her son who was taken from her, and her duty to raise her grandson. When it was all about her, she had her deepest emotions and was wrathful and vengeful, and after she is made to realize that it’s not really all about her and never was, all we get is, “it jest goes to show” and “it’s a real sad story.” On the plus side, she did demonstrate some real caring for Jerry’s welfare before the end, but she’s never going to really feel bad about all the bad things she did or show a sense of regret, and that’s all there is to it. It’s good for Jerry because the past finally seems to be dead and behind them, and Hiram comments that, one day, Jerry will also inherit the Tarleton properties from his Uncle Lafe as well as the Kincaid properties, which will put him on a much better footing in life. But, somehow, it just seems unfair that Granny never seemed completely sorry for her role in all of this misery that went on for years, and I was left feeling it more than she was.

Something that I didn’t mention earlier, that I was saving for the end and my final reaction, is that Granny’s obsession with the supernatural and her belief in Lilith as a witch/witch’s ghost may not be based not only on her upbringing and religious beliefs but also in an odd human phenomenon that even modern people experience. People expect the world to make sense, and we are all hard-wired to look for cause and effect. Granny has a long history of misinterpreting cause and effect, but she’s not the only one. A few years ago, I attended a lecture given by a group of ghosthunters in my home town. This group said that they are sometimes called in to investigate people’s homes when they think that they are being haunted. In one of their explanations, they implied, although did not explicitly state, that there are psychological roots in much of the haunting phenomena that they investigate. What they actually said was that most of that people who called them in to investigate hauntings were people who were already in very troubled circumstances in their lives. These were people who had suffered financial problems, work problems, marital problems, health problems, or problems with their children, and often some combination of these. Then, in all of these cases, something mysterious happened that they couldn’t explain, and it was just the last straw. People in a happier, healthier, and more stable frame of mind might shrug off something unusual that happened as just momentary bad luck or coincidence, but when someone is already on edge or paranoid, they begin to notice more and more odd things happening that they would otherwise ignore, drawing connections between them in their minds to the point where they become convinced that they are haunted and/or cursed. The ghosthunters did not call these people liars or delusional, and from the way they told their stories, they suggested that, because these people believed that they were haunted, in a way, they became haunted. For example, one man suffered a series of disasters after buying an odd mask at a garage sale to use as a wall decoration, and he became convinced that the mask was cursed. One of the ghosthunters actually said, “I don’t think this mask was cursed before he bought it. I think it became cursed because he bought it.” The disasters that befell this man would have happened to him anyway, with or without the mask, but because they happened around the time when he bought it, he kept attributing every bad thing to the mask, and it did take on a negative influence in his life. It even began to affect the ghosthunters in a negative way after they removed it from his house because they were influenced by the negativity that this man had associated with the mask, making them wonder if some problems they experienced around that time were also associated with it, even though they said that they really didn’t think so. In an odd way, the man actually became the curse on his own cursed mask because of his attitude, just as Granny may actually have been the witch that she always claimed Lilith was, even though she couldn’t see it herself. From this psychological perspective, Granny Samantha’s weird witch obsession becomes more understandable, and she does look a little more like a sad victim of circumstance. Josiah Tarleton set up a toxic situation in the beginning with his early rivalry with the Kincaids, rubbing his early successes and their misfortunes in their faces, so when bad things happened that might have happened anyway, whether the Tarletons had bought the farm next door or not, Granny developed an association between them and her misfortunes that she interpreted as cause and effect. Although, I kind of suspect that Samantha may have been a little unbalanced even before all that, making her more of a candidate for going superstition crazy than her husband, who tried to tell her that it was all just coincidence. Still, I can see that repeated misfortunes can have a negative affect on someone’s view of the world. I have to admit, even now, thinking about it from that angle, I still don’t like Granny for the way she affected innocent people around her and didn’t seem to show remorse for her actions, but this explanation for Granny’s thinking does make sense.

However, I think that the overall message of the story was a good one. Life doesn’t have convenient, tidy answers that can just be summed up in one brief paragraph of explanation. There is no short, easy answer to the question of why bad things happen to good people, and much of the time, we don’t get the full story of what actually happened in the first place because we can’t see it from every perspective, from all of the people involved. I had wondered how the Tarletons responded to Samantha throwing rocks at Lilith, but the story never said. Did they just let the matter slide because the townspeople had also been whispering that Lilith was a witch? Did Josiah actually stand up for his wife in some way? Did David tell Samantha to back down because he didn’t really believe in superstition, and she was acting crazy? At the end of the story, we still don’t know what actually caused the stable fire that killed Jerry’s parents. Was it a human accident or negligence, deliberate arson, or a lightning strike? Even the man who was there at the time doesn’t know or doesn’t say. By that point, it doesn’t matter, because what the characters were most concerned about was the relationship between Jerry’s parents and the character of the the Tarletons, especially Arabella. Having established that, they feel no need to inquire further into the matter. What happened in the past was a combination of bad luck, random chance, and personal choice on the part of the people involved, when they decided how to respond to the emergency. What mattered in the end was how everyone felt about it and what they decided to do because of it. When their feelings and circumstances changed, they were free to make a different choice of what they would do. Being open to new information is key to considering a situation from a different perspective, and a different perspective helped them to gain the new information they needed.

In the original book, Midnight and Jeremiah, the family’s money troubles and the fair are more the central plot than these family issues. Also, the lamb, Midnight, doesn’t get lost until after the fair is over. Uncle Hiram (who is apparently really Jeremiah’s uncle in the original book) and the town decide to celebrate the lamb’s victory at the fair, but the celebration startles the lamb, so it runs off in fright. Jeremiah eventually finds him near the nativity scene at the church on Christmas Eve.

The book is available to borrow for free online through Internet Archive.

As a historical footnote to this story, Jerry mentions early in the book that his family and some others in their little town have Scotch-Irish ancestry and that they migrated into Indiana from Kentucky. This is something that older families in Indiana did during the pioneering and homesteading days of the 19th century. Another book that I reviewed earlier, Abigail, is about a family who traveled to Indiana from Kentucky in a covered wagon, which is what both the Kincaids and the Tarletons did when the grandparents in the story were younger, actually around the time when Abigail takes place. Their circumstances would have been very much like the people in that story, and the girl in the story of Abigail, Susan, also learns how to weave using a loom very much like the one Granny uses in this book.

Scotch-Irish (sometimes called Scots-Irish) is not a term that is generally used outside of the United States because Scotland and Ireland are separate countries. Basically, what it refers to is people with ancestry from Scotland (largely Presbyterian) and Ireland (more specifically Ulster Protestants, who also had some Scottish and/or English ancestry) who came to the Americas in the 18th and 19th centuries, settling in the upper parts of what is now the southern United States but ranging as far north as Pennsylvania, generally covering the Appalachian region and states like Kentucky and Virginia. Regardless of which wave of immigration in which individual families first arrived or what mix of ancestries they had at that time, having settled in the same regions of the United States, families intermarried. If an individual has one of those factors in their background, it’s highly likely that they also have the other somewhere in their family tree. Even those with mostly Scottish or English ancestry tended to come to the Americas by way of Northern Ireland, which is why they and their descendants are often referred to by this combined name. Even though England isn’t mentioned in the term Scotch-Irish, these families also often have English ancestry, which you can see in many of their surnames. In fact, some argue that they may be ultimately more English in their origins than anything else. It would take closer examination of an individual’s family tree to mark their exact ancestry or combination of backgrounds, and in casual daily life in the United States, it wouldn’t really make a difference. The communities they formed in the United States lived basically the same sort of life, making them virtually indistinguishable and often interrelated. Sometimes, this name has been considered somewhat pretentious in its use, partly because one of the purposes behind its adoption was to distinguish people with Protestant ancestry from Irish Catholics who came to the United States later. Irish Catholics represent a different group of immigrants here. In spite of that, Scotch-Irish is a commonly-accepted description in the United States and gives a fair explanation of an individual’s family history when you understand basically what it means. Many of their descendants still live in the Appalachian region, but others have branched out to different parts of the country, as the families in this story did. They can be found everywhere in the United States in modern times.

Throughout the story, characters sing old folk songs and hymns, some that are traditional and some that they made up, sometimes accompanied by playing a dulcimer, a folk instrument found in many forms that is also used in Appalachian folk music. The Appalachian dulcimer is probably the one that the characters in the book used, given their background. One of the songs that stood out to me was Putting on the Style. This song comes in different versions, and I’d heard of it before seeing it in this book. It’s basically about how people play roles when they’re out in public and how the way they behave is partly because they’re fond of the image, not because it’s how they actually are in private. As the characters head to the fair at the end of the book, they sing this song and make up some verses of their own.

As another odd historical note, early in the book, when Jerry thinks about and describes the small town of Fulton Corners and how it is more exciting to a young boy than most people would think, he mentions the “haunted graveyard” because it looks old and creepy and is the kind of thing that a child might imagine to be haunted. He mentions that the monuments in the graveyard have different shapes and that the shapes mean things, like a lamb for a dead baby. This is true, and I’ve seen graves like that, even in Arizona, where I grew up. Modern American graveyards don’t do this and tend to have simpler markers, but in the 19th century, people used certain shapes to explain something about the deceased person. Lambs were for babies and very young children because they symbolized innocence and youth, and broken columns indicated a person who died unexpectedly in the prime of life. Jerry mentions other symbols in the story. Part of the reason why I know this is because I took a historic tour of the local pioneer cemetery in Phoenix, and also because there was an article in the local paper awhile back about some hikers who stumbled across an old graveyard that was once part of a ghost town, and they helped themselves to a lamb statue that they thought would make a good lawn ornament. At the time, they didn’t know the significance of the statue, but to anyone who realizes what they took, it’s horribly creepy. The author of the article told them to put it back. This is kind of an odd digression from the story, but since this is one of few books that mentions this odd historical detail, I decided to explain it here.