The Story of the Treasure Seekers by E. Nesbit, 1899.

This story (the first in a series) is told by one of the six Bastable children: Dora, Oswald (who won the Latin prize at his school), Dicky, the twins Alice and Noel, and Horace Octavius (called H.O. for short). The narrator initially refuses to identify which of the Bastable children he is, saying that he might admit it at the end, but his constant self-praise (which begins immediately) and the way he refers to his siblings kind of gives it away. At various points in the story, he forgets that he’s trying to be mysterious about his identity and just refers to himself in the first person, although he goes back to the third person when he remembers. The children live with their father, but their mother is dead. The narrator says, “and if you think we don’t care because I don’t tell you much about her you only show that you do not understand people at all.” The story isn’t about missing their mother, but about their search for treasure. (“It was Oswald who first thought of looking for treasure. Oswald often thinks of very interesting things.”)

The Bastables are in need of money. After their mother died, their father was ill for a time. Then, his business partner went to Spain, and his business hasn’t been very good since. The children can tell that their father is economizing on household goods. He’s sold some things from the house, there doesn’t seem to be money to have broken things fixed or replaced, and he’s let the gardener and other servants go. He’s not even sending the children to school right now because he can’t afford the school fees, and people have been coming to the house about unpaid bills. Oswald thinks that the best thing to do is to look for treasure to restore their family’s fortunes.

The children all think of ways that they can look for treasure. Oswald wants to become a highwayman and hold people up, but Dora, as the eldest, rejects that idea as wrong. His next suggestion is that they rescue a rich old gentleman and get a reward, but that’s a long shot. Alice thinks they should try using a divining rod. H.O. is in favor of the idea of being bandits. Noel likes books, and he wants to either write poetry and publish it or possibly marry a princess. Dicky is more practical with things like math and money, and he tells the others about an advertisement in the newspaper about a way to earn money in your spare time. Since the children aren’t going to school and have plenty of time, he thinks they should try it. He also has another idea, but he refuses to explain to the others exactly what the scheme is. Dora, as the eldest, decides that they should just try digging for treasure, not even bothering with a divining rod, because it seems like people always find treasure by digging. Since that’s the most straight-forward method any of them have thought of yet, they decide to go with that.

They recruit Albert, the boy from next door, to help with the digging. They don’t always get along with Albert because Albert doesn’t like reading and isn’t good at games of pretend. (The children seem to know that this treasure hunt is a game, although they’re still half-way hopeful that they’ll actually find something.) Still, they manage to persuade Albert, and the children begin digging a tunnel. It’s Albert’s turn to dig when the tunnel collapses, half-burying the unlucky Albert, who screams and keeps on screaming while Dicky runs to get Albert’s uncle. Albert’s father is dead, so he lives with his mother and his uncle, who used to be a sailor and now writes books. The children all like Albert’s uncle because they like his books, and he seems to know a lot. Albert’s uncle matter-of-factly digs Albert out of the hole and asks the children how he came to be buried. The Bastable children explain about their search for treasure. Albert’s uncle says that he doubts they’ll find any treasure in the area, but as he unearths Albert, he seems to find a couple of coins, which he gives to the children to divide among themselves and Albert. (It’s hinted that Albert’s uncle is just giving the children pocket money that he pretends to find.) It’s an uneven amount, so they agree that Albert can have the larger share because he got buried.

The Bastable children could have used their new pocket money as stake money for the venture Dicky saw in the newspaper, but there are some other things they want to buy, so they spend it all and have to try something else. One of the children (they disagree later about who it was) brings up the subject of detectives, like Sherlock Holmes. They think that detectives must earn a lot of money, so some of them think they ought to try being detectives. Alice says that she doesn’t want anything to do with murders because that would be dangerous, and even if they did kill someone, she would feel bad if she had to be the one to get them hanged for it. After all, surely nobody would want to kill someone more than once anyway, so there’s probably little risk that they’d do it again. (Oh, boy. Alice has apparently never heard of serial killers. Jack the Ripper had already committed his murders by the time this book was written and published.) The others tell her that detectives probably don’t get to choose which crimes they investigate. They just have to look into any mysterious situations they encounter and see what they turn out to be. That reminds Alice that she did see something mysterious herself. She got up during the night because she suddenly remembered that she’d forgotten to feed her pet rabbits, and she saw a light in a nearby house, where the entire family is supposedly away at the seaside. The children think that some criminals may be hiding in the empty house and decide to investigate. It turns out that there is an innocent explanation. Oswald accidentally falls and gets knocked unconscious during the investigation, so Albert’s uncle is again recruited to carry him home, and the uncle lectures them about spying on people.

Since another money-making scheme has failed, they decide to move on to the next idea, publishing Noel’s poetry. He doesn’t have enough poems for a book, but they remember that they’ve seen poetry published in a newspaper, so they decide to talk to the newspaper editor. Oswald and Noel go to see the editor together. Along the way, they meet a woman who also writes poetry. She reads Noel’s poems and says that she likes them, giving the boys a little stake money to get Noel’s literary career started. At first, Oswald refuses the money because he remembers that he’s not supposed to accept gifts from strangers, but the woman insists that the gift is that from a fellow writer, not a stranger, and she gives them her card. The children’s father later says that she’s famous for her poetry, although the boys had never heard of her before.

When they see the newspaper editor, he seems amused by Noel’s poetry (which includes an elegy to a dead beetle) and very interested in how and why he came to write poetry. He invites the boys to join him for tea, and they explain about how they’re trying to restore their family’s fortunes. The editor says that he’s willing to buy Noel’s poems and publish them, and he asks what Noel thinks would be a fair price. Noel isn’t sure because he originally just wrote the poems because he likes poetry, not to sell. The editor offers him a guinea, which is more money than they’ve ever had before, and the boys are impressed and accept it. The editor says that his paper doesn’t normally publish poetry, but he can arrange for it to be published in a different paper. They later see a story in a magazine about them, written by the editor, with all of Noel’s poems with it. Oswald isn’t happy at how the story describes them, but Noel is pleased that he’s been published.

The book continues from the summer through the fall, and the children continue trying various money-making schemes, with varying degrees of disaster and success. Noel finds a princess to marry, but they only get a few chocolates out of that adventure. While Dora is away, visiting her godmother, the other children turn bandits on Guy Fawkes Day. The only person they can find to kidnap and ransom as bandits is Albert, who doesn’t like this game at all. (The children again seem to realize that this is only a game, but at the same time, they hope for a little money out of it.) They write the ransom note for Albert using H.O.’s blood because this adventure was his idea (although they also have to use red ink to finish it because they don’t get enough blood from H.O.’s finger). Albert’s uncle, who enjoys a good game of pretend, comes to ransom Albert, although he can’t pay the enormous sum mentioned in the ransom note. He tells the children that he knows it’s all a game, and he thinks a little more pretend play would do Albert good (Albert doesn’t have much imagination), and the rough play is also punishment for Albert sneaking out of the house while he should have been inside, nursing his cold. However, the uncle says they should have realized how scary that ransom note could have been for Albert’s mother if he hadn’t seen Albert with the children and knew where he was and what was really happening. The children apologize and admit that they don’t think much about people’s mothers since they lost their own. (Although the book is mostly funny, there are sentimental bits, too.)

Albert’s uncle suggests a more harmless money-making scheme to the children – starting a newspaper, and they let Albert join them. Their newspaper contains a couple of serial stories (that don’t entirely make sense, and some of the children can’t think what to contribute to them), some poetry by Noel, some “Curious Facts” (that aren’t entirely factual but are very curious), and an editorial piece on the subject of education by Alice, who says that if she had a school, nobody would learn anything they didn’t want to learn, but there would be cats, and the students would sometimes dress up like cats and practice purring. The newspaper turns out to be not very lucrative, and the children run out of things to write about, so they give that up and return to more hair-brained schemes.

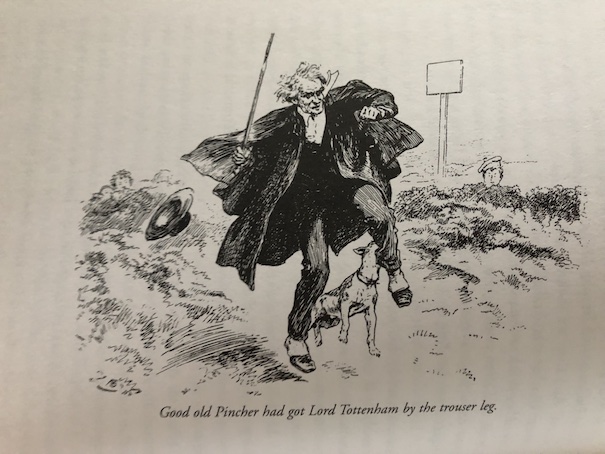

Oswald tries to rescue an elderly gentleman so that the wealthy old gentleman will richly reward him, just like in books, but not finding any danger to save him from, he sets their dog on him, so he can easily save him. The gentleman, a local lord and politician, figures out pretty quickly that this was a scheme and that the dog belongs to the children, and he demands an explanation. The children explain to him about trying to restore their family’s fortunes by doing the things that seem to work for people in books, only nothing they’ve tried works like it does it books. The old gentlemen gives the a lecture about honesty and honor and consideration for other people, and the children make their apologies to him.

From there, they try the part-time job advertised in the newspaper, which turns out to be getting people to place orders for wine by giving them free samples. The children try a little of the wine themselves, but they don’t like it, so they add a bunch of sugar to try to improve the taste. You can imagine how well a group of children trying to give various strangers free wine goes. Eventually, someone confiscates the bottle and tells their father what they’ve been up to.

Although they promise their father that they won’t attempt to go into business again without talking to him about it, they start thinking that they could make a lot of money if they invented a wonderful medicine that would cure something. After arguing about what they’re going to cure, they decide they’re going to cure the common cold. The only way they can think of inventing the medicine is for one of them to get a cold and then for all the others to try various things to cure it. Noel is the one who catches cold, and the others try to cure him. When they can’t cure Noel’s cold, they worry that he’s going to die from it, but fortunately, he does recover.

However, there are times when the children do things that are helpful, typically by accident. The best thing they do is to be extra friendly to a man who comes to see their father. The children come to the conclusion that he’s a poor man and that their father is being kind to him, but they’re not satisfied with the level of hospitality that their father offers. The children decide to invite him to their kind of dinner, and the fun they have together encourages him to give their father the help he needs. The children come to the conclusion that, sometimes, life can be like books.

The book is now public domain, so it is available to read online through Project Gutenberg (also in audio format) and Internet Archive (multiple copies, including audiobooks). There is also a LibriVox Audiobook on YouTube. It’s the first in a series of books about the same children. The story has also been made into movies multiple times. The original book contains some inappropriate racial stereotypes and language, which I discuss below. However, recent reprintings of the book have changed some of the inappropriate language, so the book would probably be okay for modern children, if you pick a book with a recent printing date.

My Reaction

I really enjoyed this story, even though there are some problematic racial issues, which I’m also going to describe and discuss. The descriptions of the children’s schemes and escapades are very funny, and I laughed out loud at some parts. The story reminds me of some of the MacDonald Hall books where the boys do some bizarre fund-raising efforts or try to get publicity for their school. The children’s efforts to find or earn money in this book are based on books that were popular with children in the late Victorian era and money-making schemes that existed at that time. Not all of them would be as familiar to modern children as they would have been to children of the late Victorian era, but I think modern children could understand most of them, with the possible exception of the man who I think was supposed to be a money lender.

If this book was set in modern times, in the early 21st century, I think that their bizarre money-making schemes would be a little more like those in the MacDonald Hall books, although I can think of a few more. Alice’s description of the ideal school, with cats who teach students how to purr, makes me think that, if she were a modern girl, she would want to start a cat cafe out of their house using a bunch of stray cats (or maybe some borrowed from neighbors without permission), which would also be hilarious. I would like to see a book with someone doing something like that because the opportunities for things to go wrong would be both boundless and guaranteed to happen. (Corralling the cats, possibly abducting cats from neighbors, messing up the tea and food, health violations, lack of business license, cats biting and clawing people and messing up the house and trying desperately to escape, etc.)

One thing that I like about the Bastable Children series in general is that there are many references to books that children from the late Victorian era would have known and enjoyed. This book references things that I think came from the Arabian Nights, and the children refer directly to Sherlock Holmes, The Jungle Books, and The Children of the New Forest, which was a 19th century historical novel.

Reality vs Pretend

Much of the book is about the difference between reality and pretend, and the Bastable children often end up about halfway between the two with most of their schemes. They draw much of their inspiration from books they’ve read, and they seem to be aware that much of what they do is a game of pretend, although they also seem to halfway hope that their schemes will work out for them the way they would if they were children from the books they’ve read.

The children’s innocence and naivete about the way the world works is a major reason why they don’t understand how things work differently between the real world and the world in stories. It’s also the reason why they only seem to halfway grasp their father’s money troubles and the reasons for them. Adults often find the innocence of children to be charming, and the adults in the story are often charmed by the children for that reason. It works in their favor in the end because they receive kindness from adults for being charming, innocent children, who know how to have fun. However, the adults in the story also understand the children’s family situation, seemingly even better than they do, and they frequently humor them and help them out of pity. It’s both funny and also a little sad and touching at times for adults reading this book. It’s funny because you can see what the children are really doing and follow their logic as they map out their plans, while at the same time spotting how it’s all going to go wrong before the children see it themselves. It’s also a little sad and worrying because you can also see how little the children are being supervised and how much they turn to the kindly uncle who lives next door for help when they’re in real trouble because their mother is dead and their father is wrapped up in his own troubles.

The subject of the children’s deceased mother comes up periodically throughout the book, as the children think about how things have changed for the family since she died. Dora admits to Oswald that, before their mother died, she asked Dora to look after the younger children. That’s why Dora has been trying to be responsible and to stop the other children from doing things she knows are wrong (like turning into bandits to rob people for money). The other children often get irritated with her for stopping them from doing things they want to do, and they frequently do the wrong thing anyway, even if they have to go behind her back to do it. Oswald develops some sympathy for Dora when he realizes that she’s been trying to do a difficult job that she doesn’t really know how to do, and he talks to some of the other children about going easy on her.

Racial Issues and Gender Stereotypes

This book has been reprinted many times since its original publication, and modern editions have been edited to remove inappropriate racial language. The original book has multiple places where there are racial issues and gender stereotypes, although they mostly come from two very specific sources. The gender stereotypes, which are found in other books in this series as well, come from our narrator, Oswald. Oswald has noticed that his sisters and other girls have different standards from him and his brothers, and it sometimes irritates him. Like other boys in vintage children’s books, he also has a tendency to try to show that boys are better than girls, sometimes saying things like, “Girls think too much of themselves if you let them do everything the same as men.” I partly think that the author, who was a woman, put things like that in her stories to show how boys of her time behaved, but maybe also to poke fun at men who felt threatened by women doing things that were considered for men only, like they’re little boys, feeling threatened by sisters who can do what they do.

Much of the racial issues in the story come from the children’s playacting, which is again based on the books they’ve read. They frequently refer to “Red Indians”, by which they mean Native Americans. Based on what they’ve read from books, American Indians are fascinating and exciting but also savage, and they love all of that. Actually, now that I think of it, that stereotype isn’t a bad description of the Bastable children themselves. They are somewhat savage or semi-feral in their behavior at times, although they would probably hate being called that. They’re certainly not tame children. I don’t entirely blame the children in the story for having misconceptions about other people because children can get misconceptions from things they read, see, or are told by adults. I don’t entirely blame the author for depicting the kind of misconceptions children have, either, especially because the Bastable children’s misconceptions make up a large part of the story and its humor. What is more concerning to me is the original sources of these misconceptions, the things that children get from people who should know better, who might even actually know better but who spread misconceptions anyway for their own purposes.

Whether the author of this book could be considered a source of misconceptions, or at least for perpetuating them, is a matter for debate. The references to other pieces of real literature and how the children use them for inspiration for what they do point to earlier books that sparked these misconceptions and racial stereotypes. I’ve always thought that the things children read early in life set them up for many of their attitudes as adults, and that’s why I think it’s unfair to expose children to literature that creates these misconceptions without an accompanying explanation about why certain attitudes are wrong or harmful and how spreading them causes problems. As adults, we often forgive children for things they do and think because we know they’re young and still learning, but children don’t stay little forever, and they need to know what is expected of them as they grow older. When they’re no longer little kids, people expect them to have a certain level of understanding about the world, the people in it, and how to treat others and speak respectfully about them. If they don’t demonstrate that kind of understanding by a certain age, many people will not take it that they’re still in the learning phase but will think that they’re being deliberately insulting or trying to provoke others when they speak inappropriately. In many cases, those people will be correct because there are people of all ages who like to push other people’s buttons to get a reaction, but I think it’s doing a great disservice to set children up for that type of conflict by trying to keep them “innocent” for too long. I’ve seen that even kids who know that there are certain words they shouldn’t use don’t always seem to understand why they’re not supposed to use them, and that half knowledge is part of the reason why they sometimes throw around nasty terms like they don’t know what they mean. The truth is, some of them really don’t. Kids like that don’t sound charmingly innocent in the 21st century. They sound dumb and clueless because they are these things. The things they don’t know are painfully obvious, and people, even possibly other kids their own age, will definitely notice and openly comment on it. The reason why they’re so clueless is that the adults in their lives who knew enough to tell them, at some point, that these were bad or shocking words to use around other people apparently didn’t explain to them why or make it clear what the social consequences for using these words would be. What I’m trying to say is not that reading this book or others of this vintage is bad, but if you’re going to share books like this with kids, with the original wording, you can’t do it properly without talking to the kids and being very direct about certain subjects. If you’re not, it could lead to problems, and it will be no favor to the child to set them up for that. The things people don’t know will almost certainly hurt them eventually and probably damage their relationships with others along the way.

The Bastable children don’t end up with damaged relationships or social consequences for the things they do because they are still young enough to be considered charmingly innocent and naive in their antics, although at least some of them would be considered old enough to know better about some things by their age. The children don’t even seem to understand the difference between Native American Indians and Indians from India until it is explained to them toward the book, when their “Indian uncle” comes to see them. The Indian uncle is the source of another racial issue in the language he uses. He’s one of the adults who says things he shouldn’t, and I need to talk about what he says and why he says it.

Readers should be aware that the original printing of this book contains the n-word. There is one use of the n-word by an adult character, toward the end of the book. It happens just once in the story, although it threw me when I reached that point because there wasn’t really anything leading up to it, so its use seemed rather sudden. It’s a shame because, up to that point, I was prepared to make some allowances for what the children say about “Red Indians” as part of their innocent ignorance, but as I said, we make allowances for the things children do that we don’t for people who are old enough to know better. The “Indian uncle” just throws out the n-word in a casual expression he uses, like “If Oswald isn’t a man, then I’m a monkey’s uncle,” except he uses the n-word instead of “monkey’s uncle.” A more recent edition of the book I’ve seen replaces the n-word with the word “fool.” I could forgive the children some of the racial stereotypes they use in some of their games because the entire premise of the story is that the Bastable children are naive and somewhat clueless, getting most of their sense of how the world works from storybooks instead of guiding adults, but things that adults say and do are different. To say that this was simply part of the way people talked during this period of history would be taking the easy way out and providing an apparent excuse for the behavior. Everyone has reasons for the things we say and do, and I’m not letting either the author or this “Indian uncle” off the hook that easily without prodding deeper into both of their motives.

The n-word isn’t something that appears in many of the children’s books I’ve read, even the vintage and antique books, because it’s a crude term. Technically, the n-word isn’t even really a word by itself but a slang corruption of a word, and it’s been considered a crudity and an insult since much earlier in the 19th century. By the early 20th century, its use was associated primarily with uneducated and unrefined “poor white trash” in the United States, and whatever their personal racial attitudes, people who wanted to be seen as educated would avoid its use. Those who did use it tended to use it in a derogatory and hostile way. Even in children’s books as old as this one, the use of crude racial terms (when they appear) are often used to establish the personality and background of the character who uses them. They appear as hints of crudeness, lack of good upbringing and moral character, and even violence and criminal tendencies (see books in the Rover Boys series for examples). Even when other characters use racial stereotypes in these stories, the use of the n-word in particular tends to signal something crude and nasty in the user’s character, something that goes beyond the other characters’ level of acceptability, especially when it comes from a character who is portrayed as being old enough and educated enough to know better. A contrast would be the Little House on the Prairie series, where characters sometimes use crude racial terms without being the villains of the story. However, the characters in the Little House on the Prairie books can still fall under the description of uneducated and unrefined. They are a poor farming family who lives much of their lives in the backwoods and on relatively isolated farms. When they associate with other people, it is most often people who are very similar to themselves, so they’re rarely in a position to get feedback from a wider society. The while the Ingalls family does try to better themselves and seek out educational opportunities later in the series, characters in those books could be considered “innocent” about certain things in much the same sense as the Bastable children are. That is, none of them know any better. The term “innocent” implies a lack of knowledge and experience as well as a lack of guilt. The Bastable children are, once again, proof that what you don’t know is obvious to others who do know, and it can hurt your image.

With that in mind, when I have seen the n-word or similar words in print, my main approach is to use it as a clue about the personality of the character who says it or about the author who wrote the dialog or both. One of the difficulties that I encountered with this particular book, compared to others, is that the author sets up the “Indian uncle” who uses the n-word to be one of the “good” characters, a rich and kindly relative who saves them all from poverty. He would seem to be in the position of someone who should know better than to use the n-word, but he does so anyway, in a casual and thoughtless way. That makes this book different from other books, where the n-word is used by characters who are definitely villains and whose use of crude language is portrayed as part of their rough and ill-mannered character. The uncle’s age and position in society wouldn’t seem to put him in the position of an ignorant innocent, and yet, he’s not portrayed as a rough villain. However, there is something else at play in this situation that I think explains who this “Indian uncle” really is and what his deal is, and that’s Victorian British colonialism.

In this series of books, adults are not always referred to by name but by their relationship to the children or the role they play in the children’s lives. In this case, the “Indian uncle” (who is never called anything else by the children, not even by his personal name) is not an “Indian” of any kind. This is just another of the children’s misconceptions because of what their father told them about him. He is apparently really an uncle of the children, and he has recently returned to England from India, but he is white and British, like the rest of their family. This is revealed in hints that go over the children’s heads at first, but which are explained more toward the end of the book.

First, the children listen in on some of the things their father and uncle say to each other when they’re having dinner, and they hear them talking about “native races” and “imperial something-or-other.” The children don’t understand what they’re talking about. Because of the books that they’ve been reading, they’re still under the impression that “Indian” means that this uncle of theirs is a Native American, but adults will put together the bits and pieces and realize that, since this story is late Victorian, the uncle has just come from India, which is under British imperial rule, and like an imperialist, he’s probably not saying many complimentary things about the “native races” there. 19th century British racial concepts were shaped by their colonization and quest for empire and were frequently expressed in a pseudo-scientific form of social Darwinism, that some races of people on Earth had evolved to be more successful than others, with the British at the top of the heap because they had successfully conquered other people and took over their land for their own use. (By this definition, I note that highwaymen and robbers should also be considered vastly superior to the people they rob because they successfully took something away from someone else. I’m sure that the Victorians would be insulted by that comparison, but I think it accurately shows the problems with this type of thinking.)

Second, when the uncle’s house is described, it’s full of taxidermy animals, most of which he killed himself (this is discussed further in the second book in the series) during his travels. That’s when it is revealed that the uncle has actually come from India and is not Native American at all, as the children had supposed. He is a wealthy man who has traveled as an adventurer, which is exciting for the children to hear about, but this is also another clue to the uncle’s personality. I noticed that the author made it a point to say that the uncle’s study was very different from the children’s father’s study because it didn’t have books in it but had those taxidermy animals. I took this as an indication that the uncle is not as much of a man of learning or business as the children’s father. He doesn’t use his study for reading and studying anything. He has money, but I’m guessing that he didn’t get it from having a profession. The children mention that their father went to Balliol College, and they meet a friend of his from his student days. Their father spends most of his time working, even though his business is suffering, and his old friend is also a family man with job (he is described as a sub-editor in the next book in the series). However, the “Indian uncle” is not described as having any profession. We don’t know if he ever attended college, but if he did, it probably wasn’t to be educated for a career. He is a man of leisure or relative leisure, who has apparently spent a good part of his life traveling around the world, shooting things and having them stuffed, and has little interest in books and studying. He’s had the money to live this kind of life, so he does it, fully confident in his superiority and ability to go where he wants and do what he likes. What I’m thinking is that this man is probably their father’s elder brother, who probably inherited money and indulged himself, while his brother studied and worked. Travel can broaden a person’s perspective, but the uncle seems to have traveled for self-indulgent adventure and excitement rather than learning about the world and the people in it. He’s got enough money that he probably doesn’t have to learn anything he doesn’t want to, and as the man who pays the bills and hires people to do things for him, he’s probably not held accountable for much. He can say and do what he likes, so he does that, without giving it a second thought, and maybe not even a first one. This isn’t explained in the course of the book, and I can’t point to much more than I already have to support it, but I think this man is meant to represent a type of wealthy British imperial adventurer.

Ultimately, what I’m saying is that the children think their uncle is a great man because he brings the family to live with him in his big house and helps their father with his business (probably by providing financial backing), so the family’s circumstances improve. He can invest money in their father’s business (the nature of which isn’t specified), and he showers the children with presents, which they love. However, as an adult, I’m noting his apparent relative lack of interest in books, intellectualism, and refinement of manners. I’m sure that the children will find him exciting to be around, but he doesn’t strike me as a learned man, a well-read one, or even a very well-behaved one. He has a lot of money, which can be used to fund the children’s education, but I don’t really trust his guidance or ability to be a role model. I also wonder if the children, who are being given an education and were definitely raised to love books, will continue to see their uncle in a romanticized way as they grow older. Few people can spend their lives traveling around, shooting things, and hiring “native races” to carry their baggage along the way. If that’s most of the uncle’s experience of life, it’s not really going to prepare the children for the future. At the time E. Nesbit wrote this book, she couldn’t have known that, about 15 year later, Europe would erupt into World War I, and boys who were children around this time, like Oswald, Dicky, Noel, and H.O., may very well have ended up being soldiers and had many of their illusions about life shattered. (I have more to say about that when I cover the next book, The Wouldbegoods.) People talk about past people being a product of their times, and in this case, the uncle and his racial attitudes are both a product of this time of imperial Britain and his own wealth, and nobody outside that bubble would see either the way he does.

That brings up the question of what the author, E. Nesbit, really thinks about these things. Does she also share the uncle’s view’s of British imperialism and other races, or is she just portraying the uncle as a type of person she observed around her in society? It’s not entirely clear because everything in the story is presented from young Oswald’s point-of-view, and he is uncritical of these things and seems to have little idea of the larger picture of things. But, there are things in The Wouldbegoods that I think help clarify some aspects of that, some possibly intentionally and others possibly not.

That was a long rant/explanation, but I thought it was important to delve into the issues a little deeper. The tl;dr of it is that, while people were the products of their times, they were also the ones who made their times what they were for their own purposes, even if they didn’t think as deeply about it at the time as we do today, and what we observe about them and their behavior are clues to their personality, life circumstances, and motivations. Overall, I found the racial issues with this story to be aggravating distractions from what is otherwise a fun and funny story, and their removal from modern printings actually improves the story by removing these distractions from the plot. The modern printings are fine for kids to read.

The Movie Version

I watched the 1996 version of the movie, which emphasized the more serious portions of the book and included the character of a female doctor, who helped the family in place of the uncle from India. It wasn’t bad, but it wasn’t as funny as the original book. I’m not sure about other movie versions.

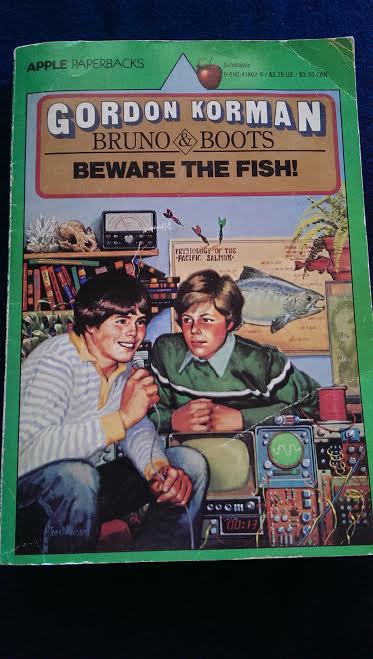

Beware the Fish! by Gordon Korman, 1980.

Beware the Fish! by Gordon Korman, 1980.