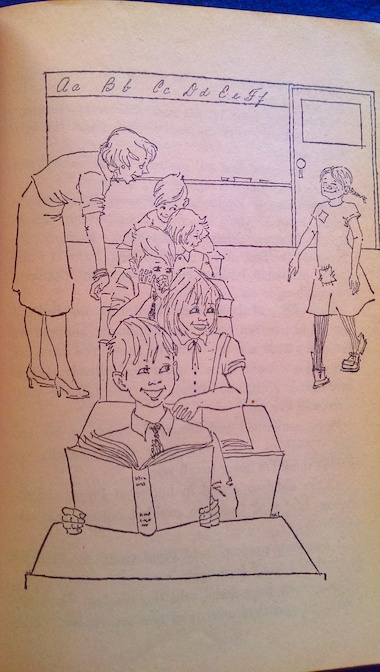

Toby Tyler; Or, Ten Weeks with a Circus by James Otis, 1881.

Toby Tyler; Or, Ten Weeks with a Circus by James Otis, 1881.

Toby Tyler is an orphan who lives with a church deacon he calls “Uncle Daniel.” Uncle Daniel isn’t really his uncle, but he raised Toby after he was abandoned as a baby. Toby doesn’t know anything about his parents. Uncle Daniel is stern with him and says that Toby eats more than he earns, making it a hardship to care for him. Toby is cared for, but life with Uncle Daniel isn’t exactly happy.

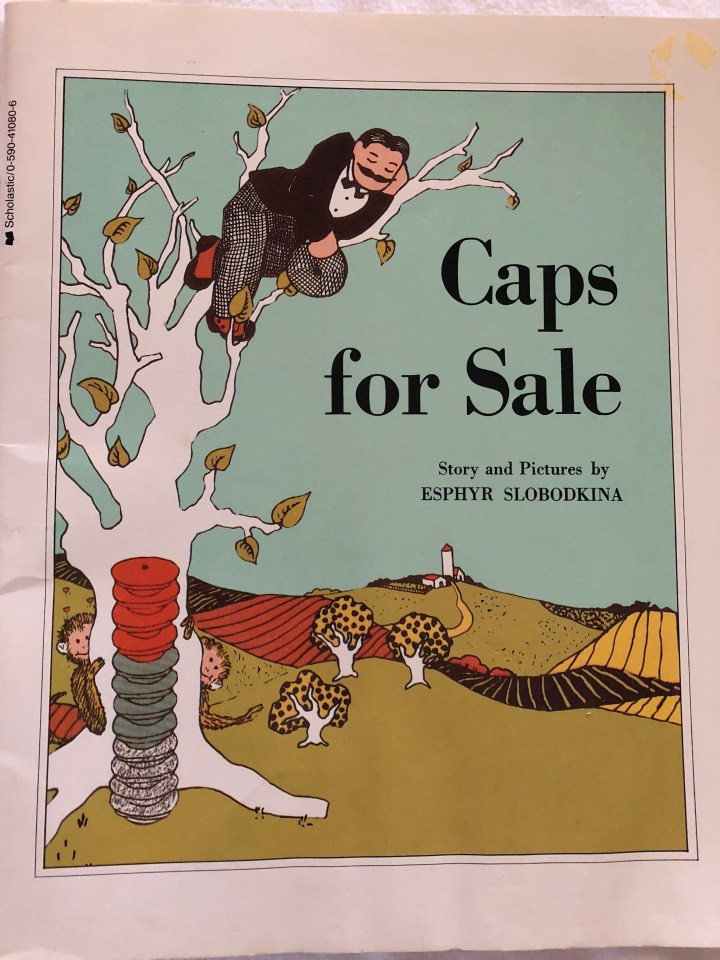

Toby has a fascination for the circus, although Uncle Daniel says that the show isn’t any good, and it’s all a waste of time and money. The circus is certainly cheap, as Toby can see from the first. When he tries to buy some peanuts, he only gets six for the penny he gives, and all or most seem to be bad. The lemonade is basically water with lemon peel in it. But, to Toby’s surprise, the man who sells the snacks at the circus, Mr. Lord, offers him a job. He says that people who work for the circus get to see the show as often as they like, and he could use a boy to help him as an assistant.

Toby think that it sounds like an exciting offer, and Mr. Lord persuades Toby that the best way would be for him to sneak away at night because his Uncle Daniel might disapprove and stop him from taking the job. Not taking that as a warning, Toby agrees. Toby feels a little guilty about running away and surprisingly homesick, but he decides to stand by the agreement he made with Mr. Lord and see what possibilities life with the circus might have for him.

Toby think that it sounds like an exciting offer, and Mr. Lord persuades Toby that the best way would be for him to sneak away at night because his Uncle Daniel might disapprove and stop him from taking the job. Not taking that as a warning, Toby agrees. Toby feels a little guilty about running away and surprisingly homesick, but he decides to stand by the agreement he made with Mr. Lord and see what possibilities life with the circus might have for him.

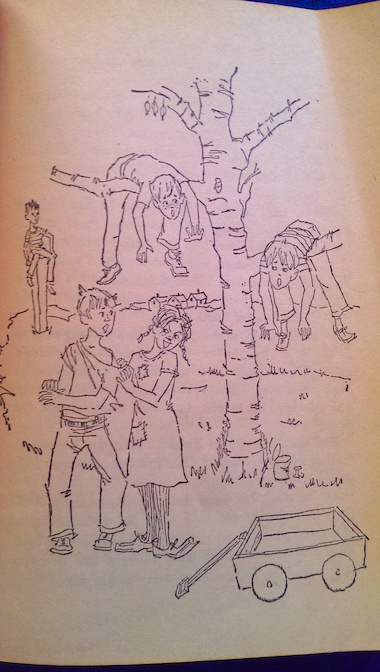

Life with the circus turns out to be very different from what Toby is used to and what he expects. It’s noisy and dirty, and no one seems to particularly care about Toby or his welfare. Mr. Lord also turns out to be even sterner than Uncle Daniel, not even telling Toby what he expects him to do, just expecting him to do it. Toby works hard, and Mr. Lord acknowledges that he’s better than the other boys who have helped him, but he’s still a temperamental man and hard to please. Like Uncle Daniel, he fusses about how much Toby eats. Toby also has to sell snacks inside the big top under the watchful eyes of Mr. Jacobs, who threatens him with violence if he doesn’t make sales or if people try to cheat him.

However, Toby does succeed in making a few friends in the circus. The first friend he makes is a monkey that he calls Mr. Stubbs. Mr. Treat, who plays the part of the Living Skeleton in the circus sideshow, and his wife, who is the Fat Lady, have seen Mr. Lord mistreating other boys, and they intervene to make sure that Toby is all right, giving him food when Mr. Lord doesn’t. Unlike everyone else Toby has known, Mrs. Treat lets him eat as much as he wants without worrying, saying that some people just need more food than others. Like her husband, Toby seems to have the ability to eat a lot while still being small and skinny. Mrs. Treat herself maintains an enormous size while hardly eating anything. She says that’s just how some people are.

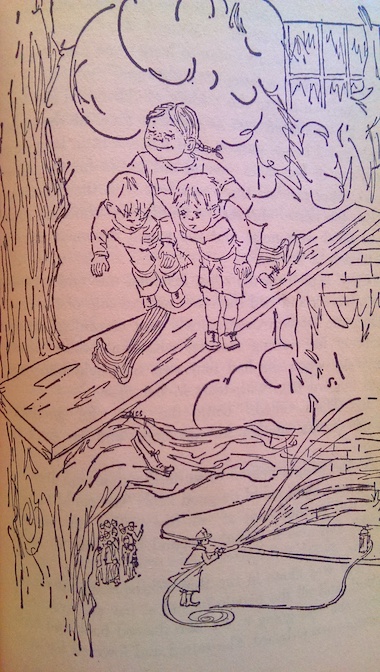

When Mr. Castle teaches Toby to do trick riding, his status goes up in the circus, and he is no longer under Mr. Lord’s thumb. As far as the Treats are concerned, Toby could stay with them forever. However, life in the circus isn’t what Toby had once thought it was, and Toby can’t get rid of the thought that he’s made a terrible mistake by running away from Uncle Daniel. He wants to go home and make things right with him.

In the Disney movie, Toby stays with the circus, doing well with his trick riding act and having happy adventures with his monkey friend. Unfortunately, in the book, Mr. Stubbs is accidentally shot by a hunter and dies. The book was meant to teach moral lessons about responsibility, whereas the movie was just about fun and adventure.

In the end of the movie, Toby stays with the circus even while being reunited with the people who raised him and missed him when he ran away, giving an all-around happy ending. In the book, Toby feels terrible about the death of Mr. Stubbs (although it wasn’t really his fault), and the hunter who shot him is very sorry because he hadn’t realized that he had shot someone’s pet. To make up for it, he helps Toby to get back to Uncle Daniel. At first, Toby is unsure that Uncle Daniel will want him back, but he misses his old home so much that he says he doesn’t care if Uncle Daniel whips him for running away. However, Uncle Daniel has also missed Toby since he disappeared. As stern and harsh as he could be before, Uncle Daniel genuinely cares about Toby and welcomes him back with open arms. The ending implies that Toby’s future with Uncle Daniel will be happier than the past because they have much greater appreciation for each other now.

The book is now in the public domain and is available on Project Gutenberg.