Pippi Longstocking by Astrid Lindgren, 1950.

Pippi Longstocking is an iconic figure in children’s literature, a little red-haired girl with amazing strength (she can lift a horse all by herself) and a quick wit, who can “always come out on top” in any situation and is frequently doing exciting and hilarious things without adult supervision. The books in her series were originally from Sweden, with the first one written in 1945, but I’m reading a later English translation.

In the first book, she comes to live by herself in a house, which she calls Villa Villekulla, in a small town in Sweden when her father, a ship’s captain, is washed overboard at sea. Although others fear that he is dead, Pippi thinks it more likely that he was washed up on an island of cannibals, where he will soon be making himself their king. (Of course, Pippi turns out to be right, but that’s getting ahead of the story.) Her mother died when she was a baby, so Pippi now lives all by herself, except for her pet monkey and horse. She pays for the things she needs with money from the suitcase of gold coins that her father left for her and spends her time doing just as she pleases.

Tommy and Annika, the children who live next door to Ville Villekulla, are perfectly ordinary, basically obedient children, who live normal lives with their parents. When Pippi moves in next door, their lives get a lot more exciting. The first time they meet her, she’s walking backward down the street. When they ask her why she’s doing that, she says that everyone walks that way in Egypt. Tommy and Annika quickly realize that she’s making that up, and Pippi admits it, but she’s such an interesting person that they accept her invitation to join her for breakfast. They’re amazed when they find out that Pippi has no parents, only a monkey and a horse living with her, and are entertained by the tall tales that she tells.

When they go back to see her the next day, Pippi tells them that she’s a “thing-finder” and invites them to come and look for things with her. Basically, Pippi is a kind of scavenger, looking for valuable things, things that might be useful, or (which is more likely) just any old random junk that she might happen across. Pippi does find some random junk, although she makes sure that Tommy and Annika find better things (probably by hiding them herself).

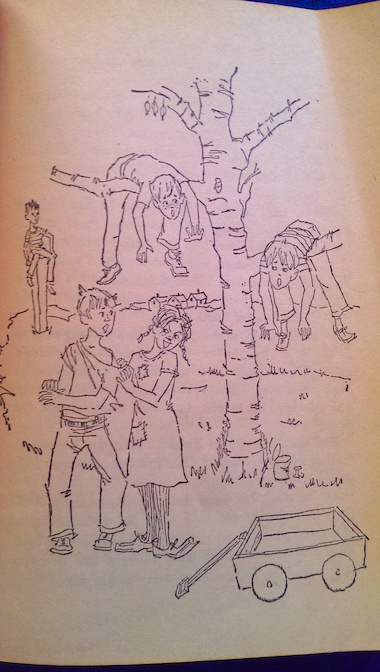

Then, the children see a group of bullies beating up another boy and decide to intervene. The meanest of the bullies, Bengt, starts picking on Pippi, but picking on a girl with super strength isn’t the wisest move. She picks him up easily and drapes him over a tree branch. Then, she takes care of his friends, too.

Word quickly spreads through town about this strange girl. Some of the adults become concerned that such a young girl seems to be living on her own. A couple of policemen come to the Ville Villekulla one day to take Pippi to a children’s home, but she saucily tells them that she already has a children’s home because she’s a child and she’s at home. Then, she tricks them into playing a bizarre game of tag that ends with them being stuck on the roof of the house. The policemen decide that perhaps Pippi can take care of herself after all and give up.

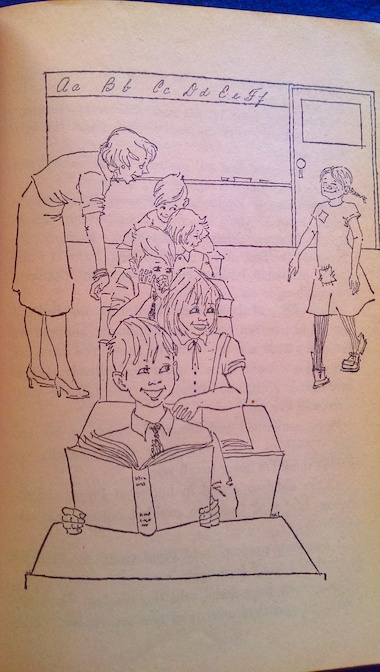

Tommy and Annika try to persuade Pippi to come to school with them, but that doesn’t work out, either. Pippi, completely unfamiliar with the routine of school, thinks that the teacher is weirdly obsessed with numbers because she keeps demanding that her students give her the answers to math problems that Pippi thinks she should be able to solve on her own. The teacher concludes that school may not be for Pippi, at least not at this point in her life.

Tommy and Annika delight in the wild things that Pippi does, like facing off with a bull while they’re on a picnic, accepting a challenge to fight a strongman at the circus, and throwing a party with a couple of burglars. When they invite Pippi to their mother’s coffee party, and their mother’s friends begin talking about their servants and how hard it is to find good help, Pippi (having already devastated the buffet of desserts and made a mess in general) jumps in with a series of tall tales about a servant that her grandparents had, interrupting everyone else. Tommy and Annika’s mother finally decides that she’s had enough and sends Pippi away. Pippi does leave, but still continuing the story about the servant on the way out, yelling out the punchline from down the street.

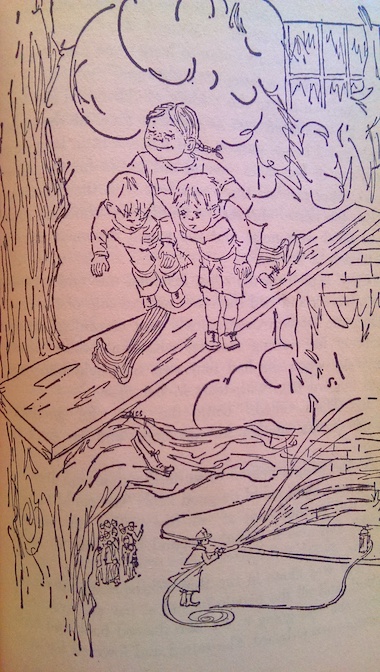

However, Pippi becomes a local hero when she saves some children from a fire after the fireman decide that they can’t reach them themselves.

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive.

My Reaction

I have to admit that, as a character, Pippi sometimes annoys me with her obvious lies and some of the stuff she does. She openly admits that she lies after telling some of her tall tales, but it’s the parts where she admonishes her listeners not to be so gullible that get to me. You can tell that her listeners aren’t really fooled at all; they’re just trying to be polite by not calling her a liar directly, and then she insults them for it. Maybe it’s Pippi who’s really the gullible one, thinking that she’s fooling people when she isn’t really.

Admittedly, Pippi’s wild stories are sometimes amusing. I liked the one where she claimed that the reason why other people don’t believe in ghosts is that all of the ghosts in the world live in her attic and play nine-pins with their heads. When Tommy and Annika go up there to see them, there aren’t any, of course, and Pippi says that they must be away at a conference for ghosts and goblins.

I just don’t like it that Pippi seems to be deliberately trying to make people look dumb when she’s the one saying all the stupid stuff and it’s really obvious that people know it. I also don’t like the part where she makes such a mess at the coffee party because she seems to be trying to be a messy pain on purpose. She insists that it’s just because she doesn’t know how to behave, but I get the sense that it’s just an excuse and that Pippi just likes to pretend to be more ignorant than she is, pushing limits just because she likes to and because she usually gets away with it. I didn’t think it was very funny. But, Tommy and Annika seem to just appreciate Pippi’s imagination, enjoying Pippi’s antics, which bring excitement and chaos to a world controlled by sensible adults, which can be boring to kids, and accepting Pippi’s stories for the tall tales they are, playing along with her.

Pippi herself is really a tall tale, with her super strength, her father the cannibal king, and her ability to turn pretty much any situation her to advantage. Part of her ability to “come out on top” is due to her super strength and part of it is that Pippi approaches situations from the attitude that she’s already won and isn’t answerable to anyone but herself. This approach doesn’t always work in real life (I can’t recommend trying it on any of your teachers, or worse still, your boss – not everyone is easily impressed, especially the people who pay your salary), and nobody in real life has Pippi’s super strength to back it up. The adults in the story frequently let Pippi win because they decide that fighting with her just isn’t worth it. (Admittedly, that does happen in real life, too. I’ve seen teachers and other people give in to people who are just too much of a pain to argue with because they’re too impatient or find the argument too exhausting.) Kids delight in Pippi’s ability to get the better of the adults, who usually have all the control, and in Pippi’s freedom to do what she wants in all situations.

One thing that might surprise American children reading this story is that the children in the story drink coffee. Tommy and Annika say that they are usually only allowed to drink it at parties, although Pippi has it more often. It isn’t very common for American children to drink coffee in general because it’s usually considered more of an adult’s drink and because of concerns about the effects of too much caffeine on young children. Children in Scandinavia tend to drink coffee at a younger age than kids in the United States.

Bed-Knob and Broomstick by Mary Norton, 1943, 1947.

Bed-Knob and Broomstick by Mary Norton, 1943, 1947.

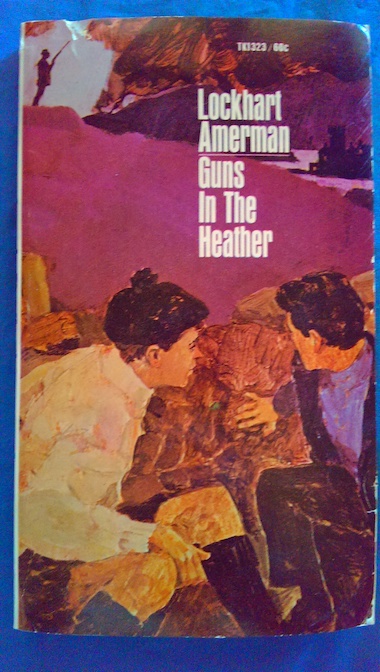

Guns in the Heather by Lockhart Amerman, 1963.

Guns in the Heather by Lockhart Amerman, 1963.

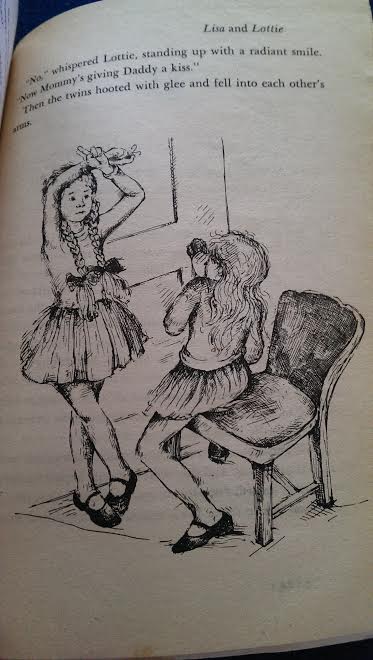

Lisa and Lottie by Erich Kastner, 1969.

Lisa and Lottie by Erich Kastner, 1969.

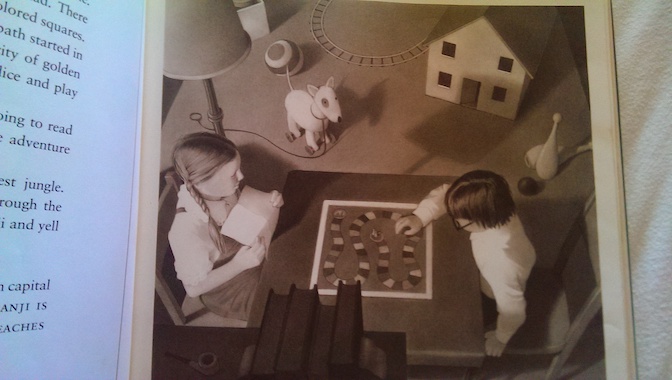

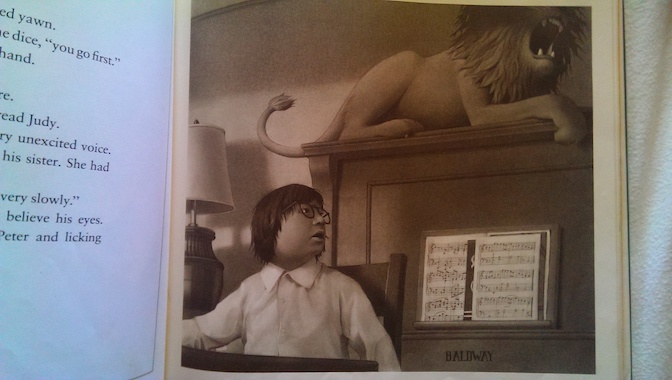

Through the rest of the summer, the girls discuss their lives and parents in great detail and continue speculating about the reasons for their parents’ separation and why they were never told about each other’s existence. They are somewhat angry at their parents for not telling them the truth, but they each also want to know more about the parent that they have never really known and perhaps to learn the truth behind their parents’ separation. They begin hatching a plot to switch places so that Lottie can go to Vienna to meet their father and Lisa can go to Munich to be with their mother. They get little notebooks and fill them with as many details of their lives as they can think of so that each girl can seem to behave like the other, although they know it won’t be easy because they’ve lived very different lives. They don’t like the same foods, and Lottie knows how to cook, but Lisa doesn’t.

Through the rest of the summer, the girls discuss their lives and parents in great detail and continue speculating about the reasons for their parents’ separation and why they were never told about each other’s existence. They are somewhat angry at their parents for not telling them the truth, but they each also want to know more about the parent that they have never really known and perhaps to learn the truth behind their parents’ separation. They begin hatching a plot to switch places so that Lottie can go to Vienna to meet their father and Lisa can go to Munich to be with their mother. They get little notebooks and fill them with as many details of their lives as they can think of so that each girl can seem to behave like the other, although they know it won’t be easy because they’ve lived very different lives. They don’t like the same foods, and Lottie knows how to cook, but Lisa doesn’t. Lisa is overjoyed to finally meet her mother in Munich. But, her mother has to work very hard as a photographic editor for a newspaper, and they don’t have much money. Lisa isn’t as good at cooking or taking care of household chores as Lottie is, so she finds it difficult to help, although she learns quickly.

Lisa is overjoyed to finally meet her mother in Munich. But, her mother has to work very hard as a photographic editor for a newspaper, and they don’t have much money. Lisa isn’t as good at cooking or taking care of household chores as Lottie is, so she finds it difficult to help, although she learns quickly. The book is much less of a comedy than either of the two Disney movies, although there are some funny parts, like when Lottie (as Lisa) takes over the household accounts to stop Rosa’s stealing and ends up turning her into a much better housekeeper with her practicality. Surprisingly, Rosa actually starts respecting her more and even liking her better because of it.

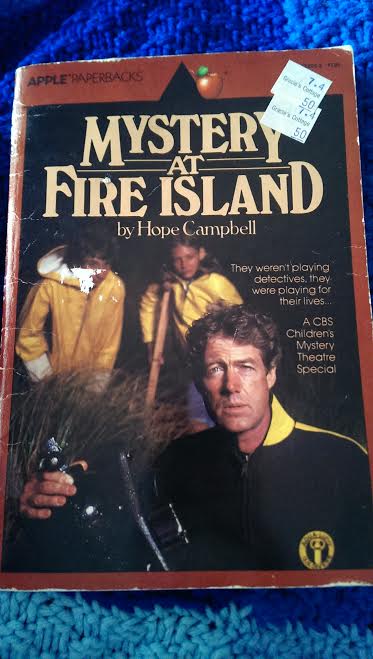

The book is much less of a comedy than either of the two Disney movies, although there are some funny parts, like when Lottie (as Lisa) takes over the household accounts to stop Rosa’s stealing and ends up turning her into a much better housekeeper with her practicality. Surprisingly, Rosa actually starts respecting her more and even liking her better because of it. The Mystery at Fire Island by Hope Campbell, 1978.

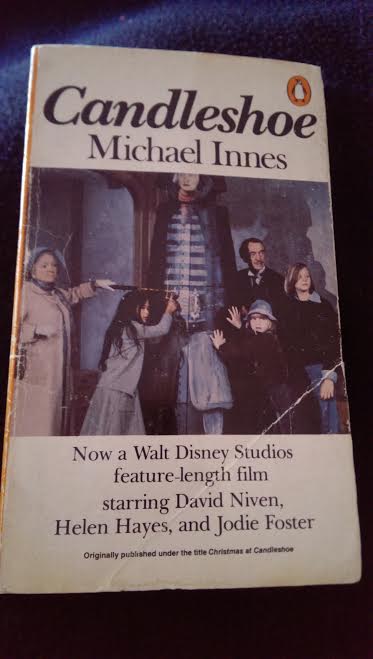

The Mystery at Fire Island by Hope Campbell, 1978. Candleshoe by Michael Innes, 1953.

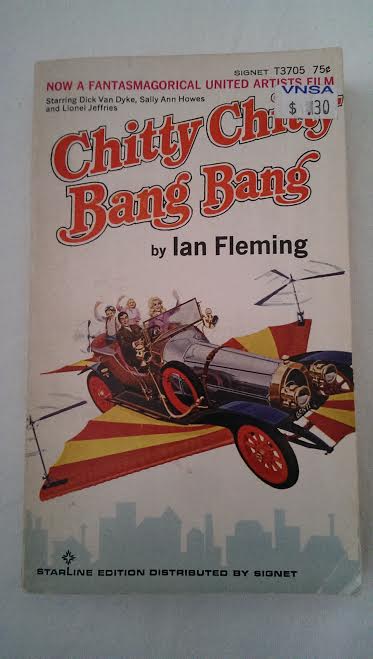

Candleshoe by Michael Innes, 1953. Chitty Chitty Bang Bang by Ian Fleming, 1964.

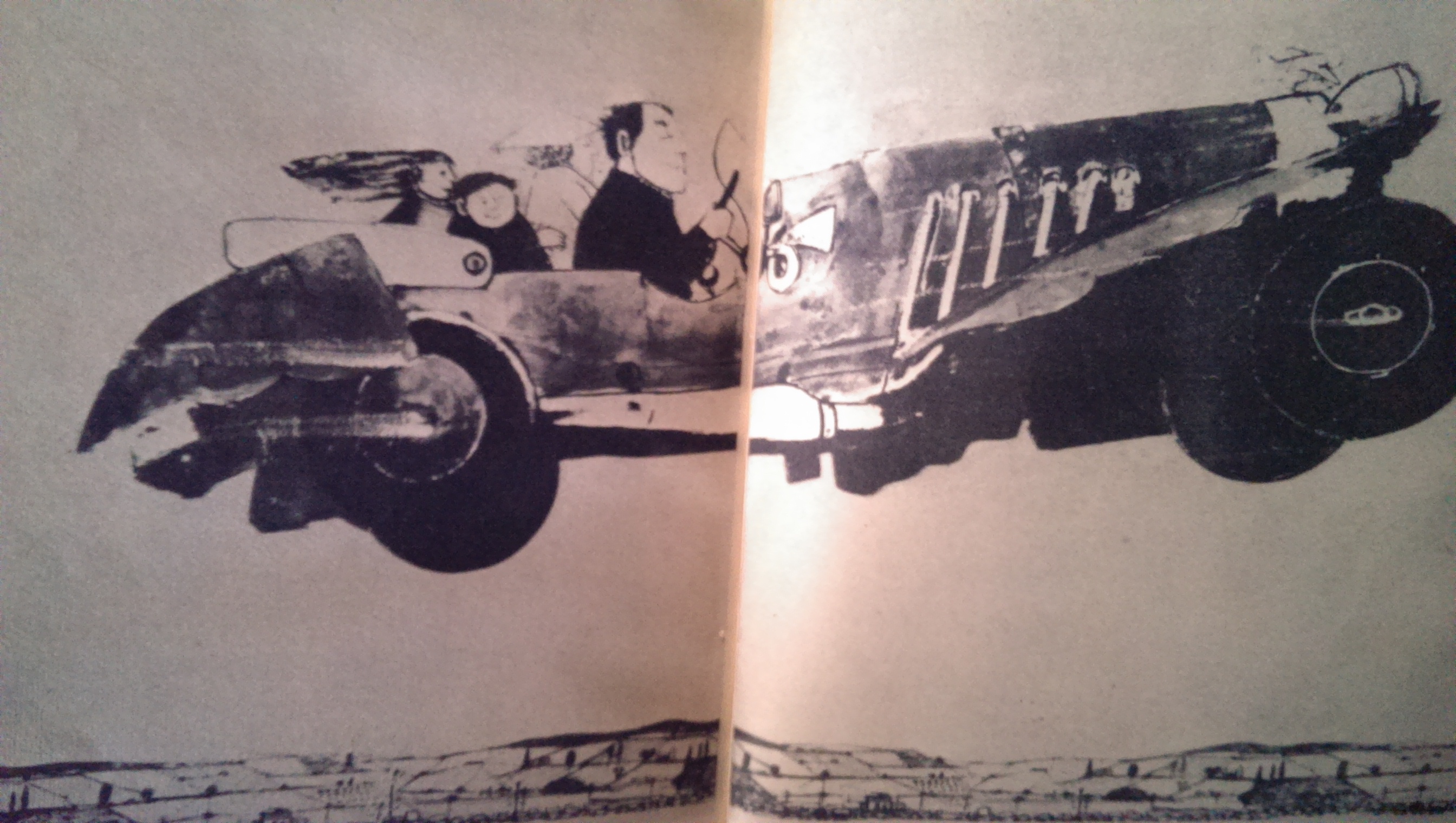

Chitty Chitty Bang Bang by Ian Fleming, 1964.