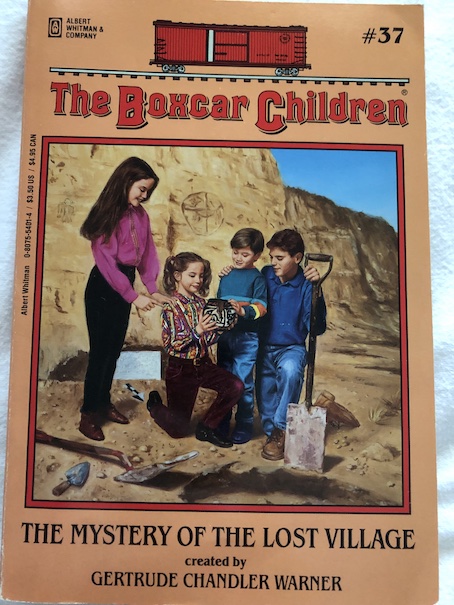

Sing Down the Moon by Scott O’Dell, 1970.

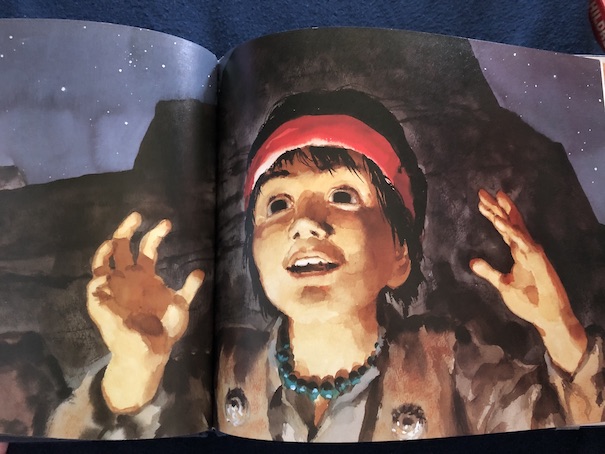

The story begins with a young Navajo girl, Bright Morning, admiring the beginning of spring, but she is caught in a storm and hurries home without the sheep she was supposed to be tending. When the girl’s mother realizes that she abandoned the sheep, she takes the girl back to the sheep, and they watch them all night. The sheep are very important to the family, and the girl’s mother refuses to allow her to take the sheep out by herself again for the rest of that spring.

When Bright Morning finally proves that she can be responsible and not leave the sheep to tend themselves, she is allowed to take them out again. Bright Morning likes to talk to the other girls, Running Bird and White Deer, as they watch all of their sheep together. The girls like to talk about their futures, who they will marry and what kind of children they have. They like to tease each other. Bright Morning’s friends know that she is likely to marry a young man called Tall Boy. The rumor is that Tall Boy’s parents want him to marry her because her mother owns so many fine sheep. Bright Morning knows that her friends tease because they are curious about Tall Boy and want her to talk about him, but she refuses. The girls know that he is supposed to be riding out with the warriors soon, and they tease that maybe he will bring back some other girl from the Ute tribe, but Bright Morning ignores them.

After the warriors have left for their raid on the Utes, the girls see some white men on horses approaching the village. The girls recognize them as oldiers and are worried that their village could be vulnerable to attack without the warriors. Later, the girls encounter more white men, but these men are not dressed as soldiers. They stop to talk to Bright Morning and Running Bird, asking them for directions, but the girls realize that they are slavers. They kidnap both girls and ride away with them!

They take the girls to a town of Spanish people and separate them from each other. They sell Bright Morning to a woman who uses her as a servant. The woman has other Native American girls as slaves, including a younger girl called Rosita. Rosita doesn’t mind her captivity or her life as a servant much. She came from a tribe that was very poor, and since she was brought to this woman’s household to work for her, she has had better food and clothing than she did at home. Rosita tells Bright Morning that the family they work for isn’t bad, and Bright Morning is allowed to keep her dog, who followed her when she was abducted. However, Bright Morning can’t stand her captivity. The woman who owns the house gives her new clothes, but Bright Morning doesn’t care. All she wants to do is find a way to go home.

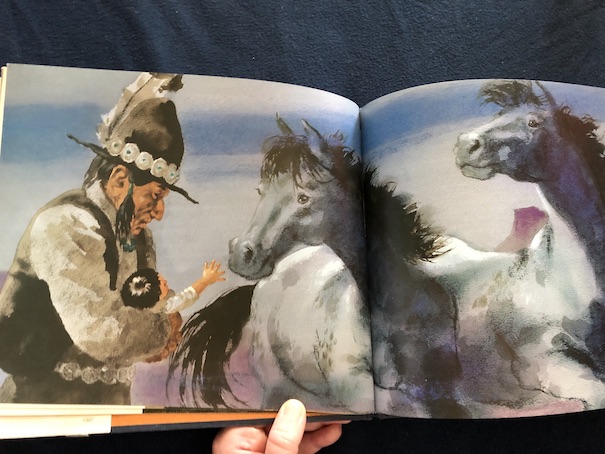

Bright Morning is reunited with Running Bird when another captive girl comes up with a plan for the three of them to escape. They manage to steal horses and ride away from the town. Along the way, they meet up with Tall Boy and one of his friends, and the boys help fight off the Spaniards who are pursuing the girls. Unfortunately, Tall Boy is badly injured in the fight. He loses the use of one of his arms, and the other Navajos know that he can no longer be a warrior. Bright Morning still cares about Tall Boy, but her mother and sister tell her that she should no longer consider marrying him.

However, the Navajos’ troubles are just beginning. They haven’t heard the last of the soldiers. The American soldiers return and drive the Navajos off their land. They destroy all of their homes and eventually round them up and start them on a long march with little food, where many of them die. The Navajos fear that all of them will die. How will Bright Morning and her family survive, and will they ever see their homeland again?

The book is a Newbery Honor book. It’s available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive (multiple copies).

My Reaction

I remember reading this book when I was about 13 years old, in middle school! It takes place in my home state, the northern part, where the Navajo reservation is now, in the Four Corners region. I’ve been to Canyon de Chelly (“Chelly” is pronounced like “shay”, like in French) before, although I hadn’t been there at the time when I first read this book. Since I read this book as a kid, I’ve been to places and seen things that helped me understand the setting of the story better. As an adult, I appreciate the historical aspects of the story even more because I know more about the background. The book doesn’t give a date for the story until the postscript at the very end of the book, but the death march described in the story is Long Walk of 1863 to 1865.

The second half of the book is very depressing because there are horrible conditions and many deaths, including the deaths of children. I wasn’t sure that I really wanted to revisit this book at first because I remembered that it was depressing, but the book is well-written. The narrator describes events in an exciting, compelling way.

I had forgotten many details of the story, but there were some things that jumped out at me as an adult that I hadn’t noticed the first time. The postscript at the end of the story explains how life and Navajo culture changed after this traumatic event. If you see photographs of Navajo in “traditional” costumes now, they often include velveteen clothing, but that’s actually a relatively new tradition. The velveteen was adopted from white people during their captivity because they didn’t have access to wool to make their older style of traditional clothing. When Bright Morning was held captive in the Spanish town, she was given velveteen clothing there.

Another odd topic that is touched on only very briefly but that I know more about from other sources concerns the subject of flour. The book mentions that the Navajo were unused to eating wheat flour until it was their only form of rations during the Long Walk. Until then, their staple grain was corn, and when they started eating wheat flour, it made them feel sick. Their bodies just weren’t used to it. The book doesn’t explicitly explain this, but I know from other sources that the Long Walk and those flour rations were the origins of Navajo fry bread. Fry bread was not part of Navajo diet until that point. I grew up eating it on special occasions as a treat because it is greasy but good with powdered sugar, and it’s often served at carnivals and fairs here. However, as an adult, I came to realize that its origins as a food come from a very dark source. It was starvation food. It can keep you alive if there’s nothing else, but it’s not going to keep you healthy if you eat nothing else. It’s greasy and fatty, and it has little nutritional quality. Even now, I don’t have as much tolerance for it as I did when I was a kid. I can’t stomach it well these days if it’s too greasy or I eat too much.

That’s actually not a bad metaphor for the events described in this book. They’re heavy, and the more of it you understand and absorb, the sicker you feel. I absorb much more now than when I was a kid and only half understood the full significance of the events, and it makes me feel much worse than I did the first time.

So, do I recommend this book for kids? Actually, yes. I’m not a fan of depressing books with a lot of death, and I struggled through some depressing books when I was in school. If you had asked my 13-year-old self whether books with this much death and suffering were worth it, she might have had trouble answering that question, but time and further understanding have changed the way my adult self feels. There are some depressing topics that are worth the struggle to absorb them, but if I were the one teaching the lessons, I think I would do it a little differently than my teachers did for me back then.

I think this book is still a good introduction to topics that can be difficult to discuss. It’s worth reading once to understand the historical background of these events and what they really meant to the people who experienced them directly. It’s painful to read the bad parts, but it’s the kind of pain that leads to something better: real understanding. I recommend the book for kids in their early teens because I think that’s the best level for understanding it and accepting the bad parts. I think it should also be accompanied by nonfiction history lessons about the time period and events and discussion about their feelings about the story and historical events. I remember being told some of the history the first time I read this book, but I think that maybe there should have been more discussion about feelings.

I think it’s important to discuss feelings because they’re the hardest part of this book and they’re also the reason why it’s difficult to study some of the darker parts of history. I had a hard time with this when I was younger, and I still do in some respects, but I think understanding what causes those feelings is key to handling them. Reading books like this while discussing tools to handle difficult feelings could help students to better handle their emotions in other areas of life as well.

One of the first points that I think is important to understand and which my teachers didn’t really explain to me is that it’s natural to feel bad when you hear about bad things happening to other people, even when the bad things happened generations before you were born or even when those individual characters are fictional. (Bright Morning and her friends and family are fictional characters even though the events around them are historical. Real Navajos did experience what they experienced.) Empathy is a natural human emotion, and it’s an important tool for living with other people. Humans are social creatures. We live as part of larger groups, and we need at least some empathy to understand other people’s emotions and circumstances, how our actions affect them, and how to treat other people as we ourselves would truly like to be treated. The ability to experience empathy is a sign that you are mentally and emotionally healthy. It’s really only worrying when someone can’t feel it.

One of the most disturbing feelings about this story comes from realizing that the soldiers who are inflicting all of this death and pain either don’t feel empathy for the people they are harming or have actively chosen to ignore it to further their own purposes. That’s not a sign of being mentally or emotionally healthy or behaving in a moral way. When the readers feel repulsed by the soldiers and what they’re doing, it’s because they recognize that these people are a serious danger to others, and they are not functioning in a normal way. Your brain is warning you of a threat. It’s a past threat rather than an immediate one, but if you find the soldiers and their actions upsetting, it’s a sign that your brain has accurately assessed the risk associated with these people and the harm they do. You have accurately connected the suffering of other people for whom you feel empathy with the people who are the direct cause. I’m not saying that the soldiers were necessarily psychopaths, but lack of empathy and remorse and calculated manipulation are all symptoms of psychopathy and should raise alarms for anyone confronted with those signs. So, feeling bad about this situation and the people causing it is a sign that you yourself are mentally and emotionally healthy and have correctly recognized the seriousness of the situation and the harm being done to other people. What I’m saying is that, even when you’re feeling bad, it’s for good reasons, and that deserves recognition.

When I was young, I felt angry and frustrated by stories where people were doing terrible things to others. I still do because that’s part of empathy, but I also came to realize that part of my frustration when it came to historical situations came from my inability to change the situation. When harm has been done, it’s impossible to undo it. What was done was done. I can’t help the people who died, and I can’t even punish the wrong-doers because they’re dead now, too. It’s frustrating to find yourself confronted by a situation where nothing can change. But, I think it’s important to realize that change has happened and is currently happening. History is being written all the time, not even just through writing but through the ways that people live their lives every day. Even when a particular event is over, events and people keep moving. Bad events can cast long shadows, causing harm long after the initial event. That’s part of what makes them so bad. However, as time moves on, new people enter the scene, and new things happen, including things that people in the past would never have foreseen. It eventually reaches a point where the things that continue to happen rely on what we, the living, continue to do or allow to be done. History takes the long view, and I think people need to be reminded of that.

Do you suppose that the people in this story who act as villains thought of themselves like that? Further point, how much does it matter how they thought of themselves? Maybe they thought of themselves as winners at the time because they were getting their way and the people they were hurting were unable to stop them from hurting and killing them, but is that really “winning”? Lazy historians frequently brush things off by saying that “history is written by the victors“, but if that were really true, would we even be hearing or reading stories like this? Would we ever hear about slaves or care about the victims of war and atrocity? Would we ever consider the perspectives of people who died at all? Or does it change your mind about what “winning” really is and who’s really a “winner”? Maybe, in life and history, there aren’t any “winners” because neither of those was ever really a contest to begin with. (Or, as some put it, life is a collection of contests that people can simultaneously be both winning and losing. Personally, I think life is just for living, not for winning against someone else who is also trying to just live and probably couldn’t care less about you “winning” or not.) Apparent victories aren’t always real accomplishments, and people who see that reality are the ones who write the most accurate histories. Individual human lives only last so long, so any apparent “win” by an individual or group is never more than temporary. Our sense of what history includes and what people in the past were really like changes as we increase our knowledge of it and reconsider the context, not unlike the way my 40-year-old self has a deeper understanding of this book than my 13-year-old self did.

Remember that, at the beginning of this particular story, the Navajo warriors were going to raid the Utes. We never really find out in the book why they were going to do this, but does it matter anymore when the Navajos themselves get raided and subjected to something that might be even worse than what they were originally planning to do to their enemies? The story drops this subplot when the march begins. Life is like that, constantly moving, ever changing. History goes on and on. Sometimes, a young warrior who was praised for his prowess gets shot in the arm and can’t pull a bow anymore. Sometimes, a 40-year-old woman from the 21st century looks back on 19th century soldiers who may have thought of themselves as heroes and wants to tell them, to their faces, that they couldn’t be more wrong about that. If they’re not evil psychopaths, they’re doing a dang good job of pretending, and I never once thought of them as being “heroes” in my entire life. That’s life for you. Each of the people who have read this book or ever will read it are among the new people entering the story and its sequels, and we all have the ability to decide what role we want to play in the on-going story of history.

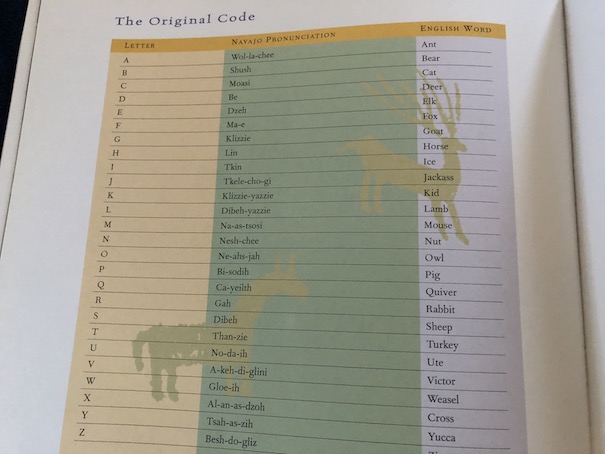

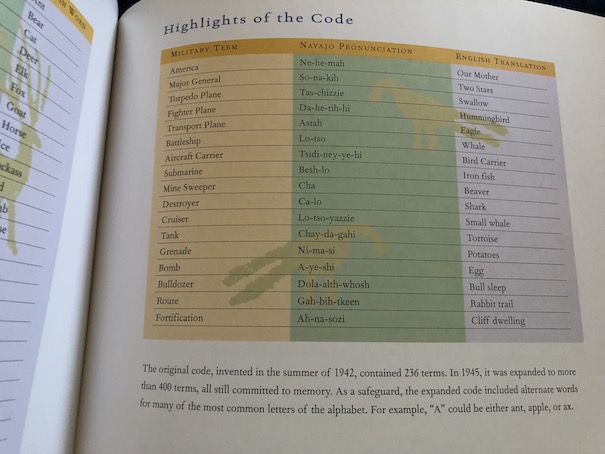

What happens after the book ends, is important, too. If I were teaching this, I would follow up this particular chapter of Native American and Navajo history by talking about some of the developments that continued to happen in their history, including some of the better moments, like the development of the written form of the Navajo language (for much of it’s history, Navajo was only a written language – that’s why the soldiers in the story couldn’t leave a written message in Navajo) and how code talkers used the Navajo language during WWII. The people who realized that these things were possible and something worth working toward were creative individuals. Rather than seeking to destroy something or repress it, they found creative ways to make use of what was there and put people’s talents to good use, helping others. The worst moments of history have been when people without empathy use others or seek to destroy them for personal gain, but the triumphant moments are when people take what they have and find a way to make it better. Noting these positive moments doesn’t make the bad parts of history any better than they actually were, but what we want is more of these positive moments of creativity and development and the type of people who are willing to work to make them happen.

It helps to balance out the explanations of what went wrong and people who did wrong with examples of what was better. Some teachers stress how we teach the bad moments so people learn from the past and don’t repeat it, and that’s true. However, I think we also need to add on what has worked and what we want people to do instead. A “don’t do this” needs to be followed up by “do this instead” to be an effective instruction. As a society, we don’t want more destroyers and takers. We want innovators and makers. We want creative people who find new uses for resources, including human resources and talents, and who are dedicated to truly helping others and human society as a whole instead of merely helping themselves to what others have that they want. This book demonstrates the dark side of humanity, but as I said, history is still being written every day with new players.

On the lighter side of this story, I enjoyed the descriptions of the coming-of-age ceremony for young women that Bright Morning has and the marriage ceremony later. During her time in captivity in the Spanish town, Bright Morning also attends Easter celebrations. She doesn’t understand Christianity and has never heard of Jesus before, and she doesn’t understand what the holiday is about or what’s going on. Rosita tries to explain to her who Jesus is in terms of Navajo religion. I found the explanation fascinating, but Bright Morning is still confused.

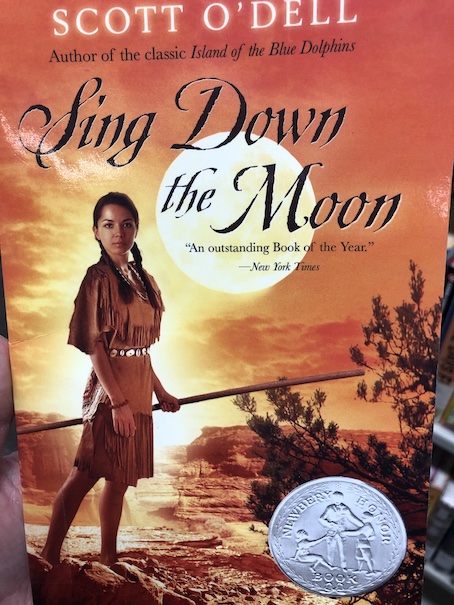

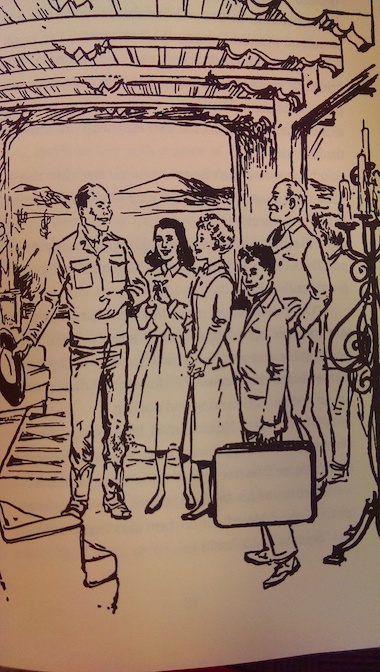

Di’s Uncle Monty (the real one, not the fake from previously in the series) has invited her and the other Bob-Whites to spend Christmas at his dude ranch near Tucson, Arizona. At first, Trixie is worried that she won’t be allowed to go with the others because her grades in school are bad and she needs to study. However, her parents finally agree to allow her to go when the boys offer to tutor her over the holidays, and Trixie can get information that she needs on Navajo Indians for her theme. It won’t be easy, though.

Di’s Uncle Monty (the real one, not the fake from previously in the series) has invited her and the other Bob-Whites to spend Christmas at his dude ranch near Tucson, Arizona. At first, Trixie is worried that she won’t be allowed to go with the others because her grades in school are bad and she needs to study. However, her parents finally agree to allow her to go when the boys offer to tutor her over the holidays, and Trixie can get information that she needs on Navajo Indians for her theme. It won’t be easy, though.