The Three Pines by Jacob Abbott, 1860.

This is the third book in the Stories of Rainbow and Lucky series. I’ve already started covering this series, and I have to do all five books in a row because the series is set up like a mini-series. That is, none of the books in the series can stand alone; they are all installments of one, longer story. They only make sense together.

It’s an unusual series from the mid-19th century, written on the eve of the American Civil War, by a white author with a young black hero. Rainbow is a teenage black boy who, in the previous installments of the story, is hired by a young carpenter who is just a few years older than he is to help him with a job in another town. The rest of the series follows the two young men, particularly Rainbow, through their adventures leaving their small town for the first time, learning life lessons, and even dealing with difficult topics like racism. (Lucky is a horse, and Lucky enters the story in this installment!) The story is unusual for this time period because it was uncommon for black people to be the heroes of books and for topics like racism to be discussed directly. It’s also important to point out that our black hero is not a slave, he is not enslaved at any point in the series, and the series has a happy ending for him. People don’t always treat him right, but he does have friends and allies, and he manages to deal with the adversity he faces and builds a future for himself. Keep in mind along the way that there are a lot of pun names in this series and that people’s names are often clues to their characters.

This particular installment in the series focuses on their arrival at their new town and what their neighbors are like. There is a racial slur in the story. Although there are hints in the earlier books, this story does particularly contain a lesson about the polite words to use when talking about black people by mid-19th century standards. I’ve explained this before, but the terms that they considered polite in the mid-19th century aren’t quite the same as what we would consider polite by 21st century standards, and the main reason for that was a cultural shift that took place in the mid-20th century with the Civil Rights Movement. Up to that point, “black” was unconsidered impolite and unflattering, and the terms “Negro” or “colored” were preferred. You can see remnants of this is the name of organizations formed prior to the Civil Rights Movement, such the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the United Negro College Fund (NCF), although those terms sound outdated today. During the Civil Rights Movements, people wanted to distance themselves from the older racial terms because they came with a lot of emotional baggage attached to them, and they wanted a fresh start. Because of that, from the late 20th century to the 21st century, the term African American has been considered the polite, formal term (some call it “politically correct”, but I think “polite” covers it well enough) and “black” has been used as the informal, generic term. One point this particular story makes, which I think applies to all eras and circumstances, is that the best policy is to refer to people by whatever terms the prefer themselves and to never call anyone something you think they wouldn’t like. One of the characters says that to do otherwise makes for “ill blood.”

This book is easily available to read online in your browser through NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICAN CHILDREN & WHAT THEY READ, I’m going to do a detailed summary below. If you’d rather read it yourself before you read my review, you can go ahead, but some people might want to know what it’s like in more detail.

The Story

The story picks up where the previous installment left off, with Tolie taking Handie and Rainbow into Southerton by wagon. On the way, Handie asks Tolie questions about the farm that he’s inherited, which is called Three Pines. The farm used to be much finer, but it has become run down, and Handie will have plenty of work fixing it up with Rainbow’s help. Handie’s plan is to get a room at the local tavern for a day or two, where he and Rainbow can stay until they get a chance to see the farm and fix it up enough for them to live there for the next two or three months, while they’re working there. His backup plan, if they can’t get a room at the tavern, is to make up beds from straw for them to sleep on at the farm because he doesn’t expect to find any furniture there. Tolie confirms that there probably won’t be any beds, but there won’t be any straw there, either. The place has been empty for some time, and it was probably cleaned out by the neighbors. They stop at a farm that Tolie knows nearby, which belongs to Mr. Workworth, to buy some bundles of straw, just in case they need it, and Tolie tells them a little more about the Three Pines farm’s neighbors.

Tolie says that the woman who lives next door to the Three Pines farm is Mrs. Blooman (Tolie calls her “Ma’am Blooman”), and he describes her as “the crossest and ugliest old vixen in town.” They pass her farm on the way into town, and they see her looking out of the window at them.

The Three Pines Farm

When they come to the Three Pines farm, they decide to go up to the house to have a look at the place and drop off the straw. The house at Three Pines is painted red, and there’s a broad field between it and the Blooman farm. There’s also a little yard around the house, surrounded by a fence, and the yard is full of litter. Tolie doesn’t see how they can get in because it looks like the house is all locked up. (I don’t know why the lawyer didn’t provide Handie with a key to the house or tell him where to find one.) Handie looks over the situation and decides that their best bet is to try one of the windows on the upper floor because he thinks that they’re less likely to be locked. They look around the barn and the shed to see if they can find a ladder, and they find a jar of wheel-grease. When Handie sees the grease, he comments that this will be useful, and he comes up with an alternate plan. With Rainbow’s help, he removes one of the doors to the shed from its hinges. They prop this door against the house, and Handie uses it to climb up to an upper window and get inside and open a door for Rainbow.

Once they get into the house, Handie says that they should make a fire in the kitchen fireplace “to drive the spooks out of the house.” The story says that neither of them really believes in “spooks” as in ghosts, but the house has a lonesome atmosphere from being empty for so long, and they know that a cheery fire will make the place feel more cozy and lived-in. Handie sends Rainbow out into the yard to pickup some chips and kindling from the yard litter that they can use to start a fire.

Since they got into the house successfully and have straw to make beds for themselves, they decide to forgo renting a room at the local tavern and just camp out in the house instead. Handie has Rainbow fetch a few things that they found while exploring the shed and barn, including the jar of grease and an old tin mug, and he uses them to make a primitive oil lamp so they will have a light while they explore the rest of the house. He explains to Rainbow what he’s doing as he works on the lamp. It’s sort of a thrown-together lamp with a short wick, but it will do for one night, and Handie promises that they will get a better lamp later.

Handie says that they will explore the house together before they go to bed. Rainbow is relieved that they will have a look around, not because he thinks the house might be haunted, but because it occurs to him that there might be some trespasser hiding somewhere, like a drunk, a crazy person, or criminals hiding out. He knows he will feel better if they look in all the rooms and make sure that there’s nobody else there. Handie is less worried about trespassers and more generally curious to see what the house looks like, so he goes first in their exploring.

The house is generally a mess, with broken floor boards, a door with a half-broken hinge, signs of a leak in the roof, and litter everywhere. Handie can see that they have their work cut out for them, getting the house in shape. However, Handie is generally pleased with the layout of the house. There is a bedroom that connects to both the kitchen and parlor, and he thinks that, when he’s old enough to get married and come to live here with his wife, she will be pleased with that room and how easily it connects to the rest of the house.

They are startled by a cat, which dashes from the house out to the barn and shed. Handie asks Rainbow to try luring the cat back to the house with some cheese, which is the only food they have that might interest a cat. Rainbow is very good with animals, and he makes friends with the cat. Handie says that cats tend to belong to places rather than people, and they tend to stay in their territory, even if the people leave. He figures that the cat just belongs to the house, and he invites Rainbow to give the cat a name, something that would be appropriate to the Three Pines farm. Rainbow decides to call the cat Pineapple. The narrator reflects that pineapples don’t come from pine trees, which are the source of the farm’s name, but Handie and Rainbow are satisfied that the name has “pine” in it.

The next morning, Handie gets up early to meet the stage coach, which delivers their luggage and his tool box. Then, he and Rainbow begin setting up for the work that they’re going to do on the farm. They start cleaning up the yard and setting up Handie’s new workshop in a back room of the house. They haven’t even had breakfast yet, so they go into town to get some food at the tavern. After they eat, Handie sends Rainbow back to the farm while he goes to see the local lawyer. As explained in the first part of the series, the lawyer who is handling Handie’s inheritance until he is old enough to take full possession of the farm himself has made arrangements to send money from his uncle’s estate to him so that he can buy what he needs to fix up the farm and to support himself and Rainbow while they’re working on the project.

Meeting The Neighbors

When Handie returns to the farm, he tells Rainbow to start sweeping the house while he starts to prepare some wood to make a workbench for himself. They don’t have a broom, and they hate to bother the neighbors to borrow one, but Rainbow says that he knows how to make one himself from hemlock, and there is hemlock growing nearby. Handie sends Rainbow to collect the hemlock and says that he will make a handle for the new broom. When Rainbow returns with the hemlock, he says that he met Mrs. Blooman. She asked him who was at Three Pines and what they were doing there. Rainbow explained to her who they were, and Mrs. Blooman gave him a kind of wild look before saying that she hoped that Handie Level would have a good time working on the farm and went away. She behaves very oddly, and Handie says she is probably unhappy because people don’t like her. Handie thinks that they should do something nice for her when they have the chance so they can make friends with her and cheer her up.

They finish up their first day on the farm by walking around the grounds and taking note of all the things they will have to do. The garden has many good plants, but it will need weeding. There’s an old summerhouse that’s in such bad condition that Handie decides they will just have to pull it down. To their surprise, they see that someone has been mending the fence at the end of the lane, but they’re not sure who did it.

As they approach the three pine trees that give the farm its name, they see a black colt that looks shaggy and wild. They wonder who owns the colt, and they notice an old man fishing nearby with a boy, so they decide to ask him. This leads to the part of the story I mentioned earlier, the conversation about the polite way to describe black people, by mid-19th century standards. The old man, called Old Uncle Giles by most people, is fishing with his grandson, Jerry. Old Uncle Giles is blind, and Jerry is helping him. When he hears someone approaching, Old Uncle Giles asks Jerry who is coming:

“I don’t know who they are, grandfather,” said he, after gazing at Handie and Rainbow a moment intently. “One of them is a black fellow.”

“Call him a colored fellow, Jerry,” said the old man. “They all like to be called colored people, and not black people. Every man a right to be called by whatever name he likes best himself.”

“But this is a boy,” replied Jerry.

“The same rule holds good in respect to boys,” added the old man. “Never call a boy by any name you think he don’t like; it only makes ill blood.”

Handie greets them and introduces himself, and Uncle Giles tells him more about the history of Three Pines farm. The story behind the three pine trees is that they were planted by the young daughter of a former owner of the farm. The man’s wife died, and he was so upset that he nearly gave up the farm and moved away. However, he had a young daughter to support, so he decided to keep the farm and tend it as best he could. As he was clearing trees from the land to plant fields, he brought his little daughter along with him because there was now nobody to take care of her at the house. His daughter asked him why he was cutting down all the pretty trees, and he explained how they had to make space for planting crops. However, his daughter saved three very small pine trees and planted them in a special little garden she made for herself. She made her father promise not to touch those three little trees, so he left them for her and protected them. That was over 70 years ago, and now, the three pine trees are tall and strong. The girl herself grew up and moved away, and how she’s 80 years old, about 5 years younger than Uncle Giles is.

Mrs. Blooman

A few days later, a little boy comes to the Three Pines farm and says that his “ma’am” asks to borrow a saw. When Rainbow and Handie try to question him about who is “ma’am” is and why she needs a saw, he doesn’t seem to know quite what to say. The little boy says that his name is Tom and points in the direction of Mrs. Blooman’s house when they ask him where he came from. Rainbow expects that Handie will lend Mrs. Blooman a saw because he said that he would like to do Mrs. Blooman a favor, but instead, Handie explains to the boy that he doesn’t have the kind of saw Mrs. Blooman needs. Handie’s saws are special carpenters’ saws, not the ordinary wood saws that someone might use for cutting up old lumber or firewood. They would be dulled if they were used for that purpose because that kind of wood probably contains old nails or sand and dirt. The boy seems a little confused, so they can only hope he understands well enough to repeat Handie’s message to his mother.

Rainbow knows that Handie could easily resharpen one of his saws if Mrs. Blooman dulls it, but Handie explains to him that’s not the point. He says that it wouldn’t really be doing someone a favor in the long term to humor an unreasonable request, and this particular request is unreasonable. She’s asking to use tools which are important to him and his work in a way that they are not intended to be used and which would damage them. Yes, he could repair the damage, but he doesn’t want her to get in the habit of thinking that it’s okay to use his tools in this way. There are limits to what another person can ask for and what favors Handie is willing to grant. ”We must help our neighbors all we can, but we must not let them loll upon us and make us carry them, instead of doing what they can for themselves.” He fully expects Mrs. Blooman to argue with him about his refusal to loan her a saw, but he also knows that’s because she doesn’t understand the nature of his trade and tools and doesn’t know how unreasonable her request is. He expects that she will come to understand and accept it eventually, and then, the neighborly relationship between them will improve.

A short time later, Tom returns and tells them that his mother says that Handie’s type of saw will do. Handie and Rainbow puzzle over what she means by “that’ll do.” Handie says maybe they’ve misunderstood what kind of task Mrs. Blooman is trying to do, since Tom isn’t able to describe it well. Since Handie is busy, he tells Rainbow to go over to Mrs. Blooman’s farm with Tom and see what the task is. If it’s a simple task that would be appropriate for a carpenter’s saw, like cutting a piece of clean lumber, they can can do that for Mrs. Blooman. If it isn’t the right kind of task for the saw, like cutting up old wood for firewood, he should explain to Mrs. Blooman herself why that type of saw isn’t appropriate for the job.

Rainbow goes over to Mrs. Blooman’s with Tom, who doesn’t really talk the entire way, even though Rainbow tries to talk to him. When they reach Mrs. Blooman, Rainbow explains the situation to her, and she reacts angrily, becoming the only person to use n-word that has appeared so far in the series:

She called Handie and Rainbow all manner of hard names, and wound up by telling Rainbow himself never to dare to show his sooty face upon her premises again. “For if there is any thing in the world that I absolutely hate,” she said, “it is a nigger.”

She is being deliberately insulting, and when she’s done with her tirade, she turns around and goes straight back inside her house. Rainbow returns to Three Pines farm and tells Handie what happened. Handie says that he is relieved that Rainbow didn’t give her any retort or that she didn’t allow him the chance to do so. Some people think that having a clever retort to crush someone who has said something rude or cruel is the best response, but Handie disagrees:

“The best thing to do when any body says any thing angry or cruel to us is not to make any reply, but to leave the sound of the words which they have spoken remaining their ears, without doing any thing to disturb it. If we say any thing ourselves we take the sound away, whereas, if we leave it there them to hear and think of, it makes them feel worse than any thing we can possibly say pay them back.”

Handie assumes that Mrs. Blooman, left alone with her own words echoing in her ears, will regret what’s she’s said and will be more civil the next time they meet her. Rainbow says that this might be likely, but he doesn’t care whether she is not. The truth is that he’s angry about the way Mrs. Blooman talked to him, although he doesn’t want to say so out loud. He is not eager to try to make friends with Mrs. Blooman.

While Handie and Rainbow are talking, the narrator says that Mrs. Blooman is feeling guilty about her behavior. It’s not because she thinks that she was unreasonable so much as she realizes that Rainbow was just the messenger for the person who refused her demands. It occurs to her that Handie is the one to blame for not lending her the saw, and it was just Rainbow’s bad luck to be the one who had to tell her. This doesn’t mean that she has any better feelings toward black people, just that Rainbow isn’t the person to blame for the immediate problem, and that she should make it up to Rainbow for that reason. Using another slur mentally, she thinks, “I need not have scolded poor blacky about it, after all … It was not his fault, I suppose, that the young curmudgeon would not lend me a saw.”

Introducing Lucky

A few days after this nasty incident with Mrs. Blooman, Rainbow sees Mrs. Blooman running down the road, trying to stop the black colt that they saw earlier. She calls to Rainbow to help, but he is also unable to catch the colt. Mrs. Blooman doesn’t blame him for this. She says that the colt, whose name is Lucky, has a habit of escaping, and it’s always difficult to get him back. Eventually, he will be caught by someone and taken to the pound, and then, she’ll have to pay to get him out again. (The narrator adds the information that Lucky’s behavior is Mrs. Blooman’s fault. She has encouraged Lucky to jump fences into other people’s pastures to graze or to just to graze along the roadsides. She has not just allowed him to be free roaming but actually encouraging in this, so she has encouraged him to develop habits that are causing problems with her neighbors, creating situations that have caused her neighbors to be angry with her.)

Rainbow volunteers to go after Lucky anyway and either try to catch him or drive him in the direction of home, provided that Handie is willing to let him go. Mrs. Blooman doubts both whether Handie will let Rainbow off work and whether Rainbow will be able to accomplish the task, but Rainbow is determined to try. As established in the previous book in the series, Rainbow loves horses and knows how to handle them. Handie allows Rainbow to go in search of the colt and lets him take some bread with him to try to lure him.

Rainbow has some strong cord, and he uses it to make a kind of halter for Lucky. When he finally spots the colt, he approaches him very carefully. He’s just making some progress with the colt when a group of boys comes along. They recognize Lucky and think it would be fun to drive him toward the pound. Rainbow speaks up and says he already has charge of the horse. The boys argue a little about it, but they finally leave Rainbow alone with the colt. Gradually, Rainbow begins feeding some bread to Lucky. He talks to him, saying:

“Now, Lucky … why can’t you and I be good friends at once, without any more playing off and on? … I’m a colored boy, it is true, Lucky; but then you can’t complain of that, for you are blacker than I am, and nobody likes you the less on that account. I am not heavy to carry, and then I shall never whip you unless you really deserve it, and then, you know, it will be for your good.”

That last part didn’t sound very reassuring to me, the reader. However, Rainbow is able to get his harness on Lucky. When Rainbow gets up on Lucky’s back to ride him home, Lucky starts running in the opposite direction from home. Lucky tries to throw Rainbow off or scare him at first, but when he realizes that Rainbow isn’t scared and loves being on his back, Lucky begins to calm down and enjoy the ride himself.

Eventually, Rainbow is able to take Lucky back to the Blooman farm. Mrs. Blooman is glad to see that he has caught Lucky and offers to pay him for his help, but Rainbow refuses. Instead, he asks if he can lead the horse around while Tommy rides him. Mrs. Blooman isn’t sure that’s safe at first, but Rainbow says it will be fine and Tommy wants a ride, so she allows it. Then, she invites Rainbow into the kitchen and gives him a big piece of pie. Rainbow is a little surprised at how tidy the kitchen is and how good the pie is, and the narrator says:

“it was very natural that he should be so, for when we find that a person is marked with bad or disagreeable qualities of one kind, we are very apt to form an unfavorable opinion of him in all respects. But when we do this we usually make a great mistake, for good and bad qualities are mixed together in almost all human characters, and nothing is more common than for a woman who is rude and selfish, and makes herself hateful to all who know her by her ugly temper and her perpetual scolding, to be very neat in her housekeeping, and an excellent cook.”

Yes, Mrs. Blooman is a definite pain-in-the-butt, obviously rude and selfish, outwardly hateful and bad-tempered to her fellow human beings, but at least, she knows how to cook and keep her house clean. I guess that’s some consolation, although I can’t help but think that the ability to make a pie doesn’t matter much in situations where you don’t actually need a pie but just need to be able to communicate with someone without them flying off the handle and becoming verbally abusive.

Mrs. Blooman asks Rainbow where he got the halter for Lucky. When Rainbow says he made it, Mrs. Blooman asks him if she can keep it for Lucky. Rainbow says that the cord he used wouldn’t be strong enough to prevent Lucky from breaking it, but he could make another one, if she has some stronger rope. She says that all she has is the rope she uses for clothesline. Rainbow has a look at it and decides that it looks strong enough, so he makes her a new halter.

Mrs. Fine

There is another house near the Three Pines farm, and that’s the house that belongs to Mrs. Fine. Mrs. Fine’s house is on the edge of Southerton, and unlike Mrs. Blooman, Mrs. Fine is a very polite woman. However, beneath her politeness, she is also cunning and scheming. It’s more that she has discovered that having pleasant manners can help her to get what she wants.

One day, Mrs. Fine wants to go somewhere in her wagon, but the man who works for her isn’t there, and she can’t harness the horse to the wagon by herself. She happens to see Rainbow passing the house on an errand for Handie, and she decides to get him to help her. Instead of just explaining the problem and asking him for help, she starts by chatting with him in a friendly way and offers him some flowers because she knows that Handie is replanting the garden at his house. Rainbow is reluctant to stop on his errand, but he feels that he has to because she’s being friendly and offering something for Handie. Then, while they’re looking at the flowers, Mrs. Fine comments that she knows Rainbow likes horses, and she invites him to come look at her horse. Rainbow says that he really needs to continue with his errand, but Mrs. Fine says that it won’t take long. Rainbow can tell immediately that the horse is difficult to handle, and then, Mrs. Fine brings up that she would like to go somewhere but can’t manage the horse herself. After all this maneuvering, Mrs. Fine could finally ask Rainbow if he can help her harness the horse, but she draws it out, step by step, first getting him to lead the horse out of the barn for her, and then, asking him if he would put on the horse’s collar. At this point, Rainbow cuts to the chase:

“If you wish to have the horse harnessed, ma’am, I can harness him for you just as well as not,” said Rainbow. “If you had told me so at the gate, I should have been perfectly willing to come and do it.”

Rainbow does harness the horse for Mrs. Fine, and later, he tells Handie about the incident. Handie thinks that it’s very funny, although Rainbow is impatient with Mrs. Fine’s roundabout way of asking for what she wants or needs. He says that, between the two of them, he thinks he likes Mrs. Blooman better than Mrs. Fine because at least she’s straight-forward.

The narrator agrees with Rainbow on this point. Mrs. Fine is in the habit of pretending that things are better than they really are, and she pushes other people to agree with her in what she pretends. Her children are often the targets of this behavior. She will often offer them something great in exchange for them doing chores, but what she gives them isn’t as good as what she promised. Then, she just pretends that she gave them what she promised. She also often assigns difficult or distasteful chores in a way that, at first, makes it seem like she’s doing them a favor or letting them have a treat. She has a smooth manner, but she takes advantage of people, even her own children. The worst part is the deceptiveness. Nobody (again, not even her own children) can trust her when she’s being nice or promising something because there’s probably going to be a catch somewhere.

Meals with Mrs. BloomaN

While they’re talking about the differences between Mrs. Fine and Mrs. Blooman, Handie asks Rainbow what he thinks about Mrs. Blooman’s cooking. Since Rainbow liked Mrs. Blooman’s pie, Handie is thinking about making arrangements with Mrs. Blooman for them to buy their meals from her instead of going to the tavern in town all the time. They can’t really cook at the Three Pines farm, and if they could get their meals next door, it would save them a lot of time going back and forth to town. Rainbow agrees that Mrs. Blooman’s cooking is good and the plan to buy meals from her would work for him.

Handie goes to see Mrs. Blooman about arranging to buy meals from her. When he gets there, Mrs. Blooman is immediately suspicious about his reasons for visiting, bracing herself for some complaint, because that’s usually why people come to see her. She invites Handie inside, and he compliments her about how neat her house is. His compliments soften her a little, but she’s still suspicious and raises the question with him about whether or not he’s come to complain about something. Handie asks her what he could complain about. Mrs. Blooman isn’t sure, but people do often complain to her, mostly about Lucky getting into their pastures. (As established earlier, this is her fault.) Handie says he’s not complaining about anything and that he thinks she’s a good neighbor. He says he’s looking forward to living next door to her when he’s old enough to take full control of his farm, although he speculates that she might have married and moved away by then. Mrs. Blooman is surprised by that comment, but Handie says he doesn’t see why she shouldn’t marry. To his mind, the only thing stopping her is her obvious capability and independence, that she seems to be managing things on her own and wouldn’t be interested in marriage. Handie is young yet, too young to get married himself, but he offers this thought about what men are looking for in a wife:

“You see, when a man looks out for a wife, he wants somebody to take care of, not somebody to take care of him. He likes to have his wife a little timid and gentle, so that she will lean upon him, and look to him for help and for protection. When a woman shows that she is perfectly able to go alone, and fight her own way through the world, he lets her go. He wants one who will lean upon him, and look to him, and let him fight for her.”

(I also think it’s important to point out that we don’t really know much about Mrs. Blooman’s backstory. We know that she must have been married at some point because she’s a “Mrs.” and she has a little boy, but we don’t know what happened to Mr. Blooman. Pressumably, Mr. Blooman is dead, and Mrs. Blooman is a widow. Since she was married once before, I wouldn’t think that the idea that she could marry again would be so surprising. She has a child, which might be a complication if she wants to remarry, but my idea is that her biggest barrier to remarriage is that she has a uncontrolled temper. I’ll have some further thoughts about Handie’s assessment of her marriage prospects in my reaction below. )

Since Mrs. Blooman brought up the subject of Lucky getting into the pasture, they discuss putting up fences, although Handie says that he will allow Lucky to graze in the pasture at regular intervals. Then, Handie brings up the topic which he really came to discuss, which is buying meals from Mrs. Blooman.

Mrs. Blooman is surprised about Handie’s request to buy meals from her, but she agrees to the arrangement. Handie will pay her regular amounts of money on top of allowing Lucky grazing time in his pasture, and Mrs. Blooman says that he and Rainbow can come to her house for their meals.

This arrangement works out well for all of them. Handie and Rainbow enjoy her cooking, and they notice that Mrs. Blooman starts dressing better and taking more care of her appearance when they come to her house. She doesn’t often receive visitors (as previously established), and Handie and Rainbow make it a point to dress as nicely as they can when they call at her house, making her feel like she should take more care to look nice as well. Handie also makes it a point to compliment Mrs. Blooman on her appearance when she looks nice, to encourage her to continue to take care of her appearance. (This is similar to how he encouraged his mother to take better care of their clothes and house in the first book by showing his appreciation every time she did something nice and complimenting the behavior he wanted to encourage. He’s using positive reinforcement.) The narrator points out:

“This is the true way to promote improvement in those who, though within the reach of our influence, are not in any sense under our control. It is not by pointing out their faults and exhorting them to amend, but by noticing what is right, and commending it, and thus encouraging them to love and to cultivate the virtue, whatever it is that you wish them to acquire.”

Handie and Rainbow also help Mrs. Blooman with some repairs to her house and yard while they’re there, and they encourage young Tommy by giving him some simple jobs to do to help and praise him when he does well. Rainbow also takes the opportunity to become better friends with Lucky. He gives him little crusts of bread as a treat, so Lucky always looks forward to Rainbow coming.

The Robin Incident

There is an upsetting incident where Rainbow comes to Handie and tells him that someone has shot a couple of robins he was caring for near the pine trees. Rainbow is so angry and upset about the deaths of the robins that he wishes he could shoot the shooter himself. Handie is alarmed, and Rainbow amends that to saying he would shoot the person in the legs with salt. It’s all talk because Rainbow doesn’t have a gun, and Handie is relieved about that. Handie says that he doesn’t think shooting someone would teach them to behave better, and Rainbow agrees, but he still feels like there should be some punishment for this.

When the shooter comes along, they see that it’s a boy who lives in the area named Alger. Handie and Rainbow confront him about what he did, Handie saying that it was a “good shot” in the sense of accuracy but not in the sense that it was a good thing to do. They explain that those two robins were parents, and they had a nest with babies in it. With the parents gone, the babies will starve if they don’t help them. Alger says that he didn’t know about the babies and wouldn’t have shot the robins if he had known. Handie and Rainbow say that Alger should get the nest and raise the babies since he made them orphans. Alger doesn’t think he can get to the nest when Rainbow points out where it is, but Rainbow helps get it down.

Alger is charmed by the babies when he sees them, and Rainbow makes him promise to take care of the baby birds and feed them properly. Alger agrees, and he plans to make pets of them. Unfortunately, he carelessly puts the nest where a cat can get at it when he gets home, and the cat eats the babies. Alger feels terrible about this, realizing that, with one shot, he destroyed an entire family of adorable birds. If he hadn’t shot the parents, they wouldn’t have taken the babies out of the tree, and if they were still in the tree, they wouldn’t have been eaten by the cat. Alger thinks to himself that he’ll never shoot another robin. “Thus, although Handie’s mode of managing the case proved unhappily unsuccessful, so far as saving the lives of the little birds was concerned, it had the effect of awakening the dormant sentiments of humanity in Alger’s bosom …” Alger’s sadness at seeing the full, awful consequences of his actions directly teaches him an important lesson about thinking before he does things and understanding that his actions affect other living creatures, something that the author reflects, he couldn’t have learned by getting shot in the legs.

Rainbow’s Party

The narrator tells us that other boys in Southerton didn’t like Rainbow when he first arrived in the area, presumably because he’s black. However, Rainbow is generally a friendly and helpful person, and he gradually won them over by helping them with problems that they had. Rainbow is physically strong and also clever, and the local boys discovered that he could help them do things that they couldn’t do themselves, causing them to turn to him when they need help with things and develop a friendlier relationship with him.

One day, some younger boys come to Three Pines farm and ask Rainbow for some wood shavings from Handie’s carpentry work because they want to make a bonfire. Rainbow asks them where they plan to make this fire, and they say that they want to make it out in the street. Rainbow says that’s too dangerous because a fire in the street would scare horses that might come along. Instead, he says that he will help them make a space in the garden for their bonfire. He takes them to a clear space in the middle of the garden and gives them some wood shavings and some matches. Then, he goes back to his work and lets them have their fire. (This sounds dangerous, too, leaving them unsupervised with matches and fire, but fortunately, nobody gets hurt or burns anything down.)

When Rainbow sees how much the younger boys enjoy the bonfire, he thinks that he should make a large one for them some evening. He plans a bonfire party and starts inviting other boys, but he only invites boys who are twelve years old or younger. The younger boys are relieved that the older boys aren’t invited because the older boys give them a hard time. Rainbow doesn’t tell them about the bonfire right away, either, because he wants that to be a surprise. He just tells them that he wants to have a party, and he says that they should bring some bread and butter for their supper because the kitchen at Three Pines still isn’t set up for cooking. When Rainbow discusses his plans with Handie, Handie approves of the party and buys some gingerbread in town for the boys’ dessert. Mrs. Blooman, whose son Tommy is also part of the party, lets the boys take some milk from her cow when they ask.

The story describes how the boys set up their bonfire, and the boys play hide-and-seek until it’s dark enough to light the fire. Everyone has a good time, and the bonfire is impressive. When the fire has burned out, Rainbow gives the boys rides on Lucky. Generally, the party goes well, nothing goes wrong, and it’s just a pleasant interlude in the story.

The Torpedo Fire Incident

The narrator says that, all the time that Handie and Rainbow have been at Three Pines, they spend an hour in the evening helping Rainbow to improve his writing skills. Sometimes, Rainbow writes letters to his mother or works on accounts, but other times, he copies quotations with some moral lesson, which he often decorates with little drawings and hangs on the walls of the room where he’s staying. One day, Rainbow asks Handie about a poem by Pope, which says:

“Teach me to feel another’s woe,

To hide the fault I see:

That mercy I to others show,

That mercy show to me.”

Rainbow asks Handie if he thinks they should always hide other people’s faults. Handie, says, yes, unless there’s a good reason for calling attention to them. As an example, he reminds Rainbow of how he revealed when he saw a thief hiding a bag with the stolen goods in the last book in the series. In that case, he had to tell what he saw so that the stolen goods could be return to the owner. However, in lesser circumstances, there is no good reason to point out every little, petty fault in other people. The narrator agrees with the principle, although he notes that it can sometimes be difficult to tell when there might be a good reason to reveal someone else’s fault or wrong-doing.

“On the other hand, in respect to the ordinary faults and foibles of our friends and acquaintances, it is plain that we ought to do all in our power to conceal them. They who take pleasure in talking over these faults and in setting them out in a strong and ridiculous light among each other, merely for amusement, evince a very unchristian and a very hateful spirit, and do very wrong. But then there is a third class of cases, in which a conscientious person is sometimes quite at a loss to know whether a certain act of wrong-doing which has come to his knowledge ought to be divulged or concealed.”

This brings us to the incident with the “torpedos,” which tests that principle and presents a case where Rainbow wonders whether or not he should tell what he knows. The story explains that “torpedos” are small explosives that some of the local boys make for fun. They roll up fulminating powder (which is highly volatile) in some paper with sand and lead shot. Because the fulminating powder is so volatile, the torpedos explode with a loud bang when the boys just throw them on the ground.

One day, little Tommy Blooman sees some other boys setting off torpedos for the first time. He doesn’t know quite how they work, but he’s fascinated. He asks the boys to set off more for him, but the other boys need to go home, so they just give Tommy a couple of torpedos for himself. Tommy thinks at first that they need to be lit with a match, like “India crackers” (I think they’re referring to fire crackers), so he puts the torpedos in his pocket and plans to go ask Rainbow for a match to set them off. When he asks Rainbow for a match, Rainbow thinks that he’s going to make another little bonfire, like the local boys sometimes do, and gives him one. Tommy wraps the match up in his pocket with the torpedos, planning to light them later. (You can see the disaster impending, can’t you? See, this is why we, as a society, discourage children from playing with matches, especially unsupervised. You just can’t make assumptions about what kids are going to do with them.)

When Tommy gets home, Joseph, the man who works for his mother, is taking Lucky into the barn. Joseph asks Tommy to help him spread some straw for Lucky, and Tommy does, but somewhere, he loses the little paper bundle he made with the torpedos and the match. Tommy returns to the yard and the barn later, looking for it, but he doesn’t see it anywhere. Fortunately, he leaves the barn door unlatched when he leaves, so Lucky is able to get out later.

Lucky accidentally steps on the bundle with the torpedos in it because it’s in his stall, and he sets them off. The loud bang scares him, and he bolts, running for the Three Pines farm. Meanwhile, the explosion and Lucky treading on the match starts a fire in the Bloomans’ barn.

When Lucky runs to the Three Pines farm, he goes to the place along the porch where Rainbow usually gives him some food, and he begins pawing with his hooves to get Rainbow’s attention. Rainbow is asleep, but he wakes up when he hears the horse and wonders why Lucky is there in the middle of the night. He looks out the window and see the fire at the Blooman barn, and he wakes up Handie. The two them rush over to the Blooman farm to help.

When they get there, Mrs. Blooman is in a panic, and Joseph is starting to work on the fire. Handie clams Mrs. Blooman down, and they help Joseph fight the fire. Eventually, they manage to put it out. Mrs. Blooman and her son go back to bed because it’s still night, and Joseph sits up to keep watch, in case there are still sparks smoldering, which can start a new fire. Handie and Rainbow go back to their own farm. In the morning, they return to the Blooman farm to see how things are.

By this time, Rainbow has had time to think, and he remembers Tommy asking him for matches. Thinking that Tommy’s request might have something to do with the fire, Rainbow questions him about what he did with the matches. Tommy reluctantly admits that he lost them and tells Rainbow about misplacing the bundle with matches and torpedos. He thought he dropped them in the yard somewhere, but Rainbow correctly realizes that Tommy lost them in barn, and that’s how the fire started.

However, Rainbow is reluctant to tell anybody what he knows. After all, Tommy didn’t start the fire on purpose, and Rainbow realizes that everyone might be really mad at Tommy for being careless with matches. On the other hand, though, Rainbow has to admit that Tommy was careless with the matches and should never have taken them into the barn. When Rainbow lets some of the boys have matches, he warns them to be careful. But, now that the fire is over, what good would it do to tell everyone about it? It’s not like the fire can be undone now. Rainbow has good intentions, although the narrator points out that there is a selfish motive in Rainbow’s concealment of what he knows because, as the person who let Tommy have matches, he is also partly to blame.

Handie later tells Rainbow that the damage done to Mrs. Blooman’s barn isn’t the problem. Mrs. Blooman had insurance, so she’s going to get some money to take care of rebuilding the barn. The real problem now is that the thinks Joseph is responsible for the fire. She thinks that he was smoking his pipe in the barn and got careless, since as far as she knows, Joseph was the last person in the barn before the fire. She is planning to send Joseph away because of his carelessness. Now, Rainbow is worried about Joseph losing his job and being falsely accused because he didn’t speak up about what he knows about Tommy and the matches.

To make sure that he really has the story straight, Rainbow talks to Tommy one more time, and Tommy admits that he went out to the barn to find the torpedos and matches after Joseph left, but he never found them. Tommy also admits that he’s the one who left the barn door unlocked because he was too short to latch it again, although he’s glad he did that now because that allowed Lucky to get out of the barn when it caught fire. Satisfied that he now understands the full situation Rainbow realizes that he needs to tell Handie what really happened so Joseph won’t take the blame. Rainbow is also willing to face whatever criticism he gets for supplying Tommy with the matches. First, Rainbow tells Handie what he knows, and then, Handie speaks to Mrs. Blooman about the situation.

Fortunately, neither Handie nor Mrs. Blooman are angry with Rainbow or Tommy. Handie believes that Rainbow has learned a lesson from this experience and doesn’t feel the need to lecture him. Mrs. Blooman no longer blames Joseph for the fire, and actually, she’s not really upset about the fire because it has allowed her the opportunity to rebuild her barn with some improvements, so she doesn’t lecture Tommy. (Personally, I thought she ought to talk to Tommy at least somewhat, pointing out that the fire shows him how dangerous fires can be and how she wants him to be careful with matches and explosives, regardless of whether or not the ones he had caused the fire. It’s not just about the fire in the barn but the future fires Tommy might cause, if he doesn’t understand that how he treated those matches and explosives was dangerous.)

With this incident behind them, Handie continues work on repairing his farm. In a few more weeks, it’s in pretty good shape, and he soon finds a suitable person to rent the farm. Before he and Rainbow return to their home town, Handie also works on the new barn for Mrs. Blooman. There are just a couple more matters to attend to. One of them is the cat, Pineapple. At first, Rainbow wants to take the cat home with him, but sadly, Pineapple is killed in an accident when a wood pile falls on her. The author describes how the accident was caused by the careless way a local girl removed wood from the bottom of the pile, probably a warning to child readers of the story. The other matter is the horse, Lucky. Rainbow has become extremely fond of Lucky, and now Lucky has a new barn to live in, but there’s more to the story between him and Rainbow, which the author promises to tell in the next installment in the series.

My Reactions

The story is episodic, like other installments in this series. Within the book, there are smaller stories and incidents. Overall, I liked it, and the author’s analysis of human nature and behavior are thought-provoking. I don’t agree with him on everything, but he does a good job of examining the feelings and motivations of his characters.

Mrs. Blooman vs. Mrs. Fine

The criminal we met before, in the previous book, spoke contemptuously of black people and didn’t want to ride inside the coach with Rainbow, but Mrs. Blooman is even more over-the-top in her reaction to being told that she can’t borrow one of Handie’s tools. So far, she is the only character in the book to use the n-word. I’ve read other vintage and antique children’s books where characters’ language, including their choice of racial language is a clue to their personal character. Sometimes, as with the criminal in the previous book, it indicates a bad upbringing and a disreputable character. Mrs. Blooman’s language is also a clue to her character, but the author takes it in a somewhat different direction, and he also introduces another woman, whose behavior is opposite to Mrs. Blooman’s, to provide further insight into both of them.

Is Mrs. Blooman actually a racist? She certainly sounds like one, and she explicitly states that she doesn’t like black people, in very crude terms. On some level, she might be, but there’s more going on with her than that. Basically, Mrs. Blooman’s worst problem is that she’s bad-tempered and has little or no impulse control. In modern terms, she has no filter, and she lacks it pretty badly. Whenever something happens that gets her angry, even if it’s a situation that she created herself (maybe even especially when she’s caused the problem herself), she lets loose with the worst, most insulting language she knows. It might be debatable how much she means what she says literally, but she certainly means the emotion behind it, and that emotion is that she wants to hurt other people’s feelings whenever she feels bad.

Handie seems to see what’s behind Mrs. Blooman and her behavior, and he uses a kind of positive reinforcement with her to draw out her better nature. He finds parts of her behavior and her nature that he wants to encourage, and he makes it a point to praise her for them repeatedly, giving her an incentive to do more of what is pleasant and less of what is unpleasant. Through this technique, Mrs. Blooman’s behavior gradually improves, and she becomes helpful to both Handie and Rainbow.

One of the points that I find difficult to believe is the idea that Handie puts forth is that Mrs. Blooman probably regrets the nasty things she says to Rainbow soon after she says them and that, if she is left to consider them, she will probably change her behavior out of embarrassment over the way she acted. Personally, I have doubts about this. I don’t doubt that such a person might feel badly or embarrassed about saying something rude; I just don’t expect that their behavior will improve that quickly because of that embarrassment. I’ve seen similar people before just dig themselves in deeper, doubling down on their bad behavior, because they feel like they have something to prove. What they do indicates that they think that, if they make any attempt to change their behavior, they would be tacitly admitting that they were wrong to do what they did, and they can’t or won’t do that because it would compromise their egos. To avoid that, they often increase their bad behavior, trying to prove that there’s nothing wrong with what they’ve done, that nobody can stop them from acting any way they choose, and because nobody can stop them or give them any consequences for their behavior, they must have been right to do what they did all along. Even if nobody else buys it, they’ll do it if they can use that to convince themselves. I’ve seen this often enough that I would have expected Mrs. Blooman to behave the same way for the same reasons, doubling down on the bad behavior save face and/or prove that nobody can control her when she can’t control herself. Like other people I’ve seen, Mrs. Blooman has ingrained bad habits and a sense that she’s entitled to take out her own bad feelings on other people. So, if she’s feeling bad again, even if it’s because she’s feeling bad about her own behavior, I would expect her either to take it out on someone else or double down on her previous behavior to try to prove to herself and everyone else that she can do what she wants and not feel badly about it. Even if she does actually feel badly about it, she still might try to repeat the behavior to prove to herself that she doesn’t need to feel bad. Lather, rinse, repeat ad nauseum.

However, I did like the author’s suggestion that it’s best to make no reply to such people when they’re being rude and nasty. Handie’s idea is that it leaves their own rude words echoing in their ears with no one’s retort to distract them from what they said themselves. I do think there’s something to this idea. In modern times, a lot of people put their emphasis on having a good comeback to crush the offender, but those can be difficult to think of in the moment, and also, there are many offensive things a person can say which just don’t have any good response. The offender can also use any rude or harsh reply that someone might make to try to blame the other person for their own attitude problems or to try to prove that the other person is no better than they are. Handie is correct that this is likely to compound the problem and distract from the real issue, which is the original rudeness. I don’t take it as a guarantee that the person will come to their senses and realize that their behavior was inappropriate, but offering no reply would at least not add any potential distractions from the real issue or fuel for further arguments.

Mrs. Fine is the opposite of Mrs. Blooman in many ways. She is far more polite in her outward behavior than Mrs. Blooman, and she is far more controlled and calculating. Mrs. Blooman lashes out without a thought, while Mrs. Fine is a schemer. Mrs. Fine’s polite veneer is a tool to get people to do what she wants, and she’s not above lying to provoke people’s sympathy and get her way. When Rainbow realizes that’s what she’s doing, he says that he actually prefers Mrs. Blooman to Mrs. Fine. Yes, Mrs. Blooman is temperamental and offensive, but with her total lack of impulse control, she couldn’t scheme or manipulate to save her life. Rainbow appreciates that, as difficult as she is, at least he knows where he stands with her. Mrs. Fine uses politeness and promises to make people feel like they can’t refuse to do what she wants, but the worst part is that she is deceptive. She often misrepresents what she wants or doesn’t fulfill her promises to the people who help her, even her own children. I would argue that she’s not fooling people as much as she thinks because people who have dealt with her before are on to her tricks. It can still be difficult to refuse her because of the way she uses what seems like politeness to make people feel obligated to go along with her, but at the same time, people who are accustomed to her behavior can tell when she’s stringing them along, that she isn’t likely to follow through on promises, or that there’s going to be a catch somewhere in any offer or request she makes. Rainbow catches on after one encounter, and Mrs. Fine’s children don’t really believe anything she says to them anymore.

Handie and Rainbow interact more with Mrs. Blooman than with Mrs. Fine in the story, so Mrs. Blooman’s behavior is examined more, and Handie finds a solution to dealing with her. They don’t deal more with Mrs. Fine, Mrs. Fine’s behavior isn’t examined as much, and Mrs. Fine doesn’t change during the course of the story. I developed a few theories of my own regarding why Mrs. Fine acts the way she does. My main theory is that Mrs. Fine’s behavior is probably a reflection of the family that raised her. I suspect that her family probably insisted on good behavior in the sense of being polite and agreeable, or at least faking it, but also made it difficult for her to ask for things she wanted and needed openly. I think that she probably developed her behavior as a coping mechanism because she felt like it was the only way for her to get what she needed from other people when she couldn’t directly ask. She still uses it when she thinks that she can’t get her children to cooperate with her just by asking them or telling them what she wants them to do. Because she doesn’t expect people to accept her real requests or her real reasons, she invents them. It wouldn’t surprise me if her own mother did that or had the habit of pretending that bad circumstances are better than they actually are to cover up for some unpleasant realities. We don’t know for sure because the book doesn’t provide her background details, but I base that theory somewhat on times when I’ve been around people who were disrespectful to me and wouldn’t accept what I said when I was voicing real opinions or concerns. Those types of circumstances can lead a person to become a bit cagey to work around difficult people. It can be awkward and embarrassing, but as I said, there are some things and some people who simply have no good response. Maybe Mrs. Fine could learn to be a little more sincere if people made it clear that they want to know what her real needs are, that it’s safe for her to be honest with them, and that they refuse to play along with her when she pretends that things are other than they really are, but that’s just my theory.

So, do I agree with Rainbow’s assessment that blunt Mrs. Blooman with the faulty filter is easier to get along with than the slick Mrs. Fine? Actually, I didn’t like either of them. Mrs. Blooman improved her behavior, which made it easier to follow her the rest of the story, but I refuse to accept the premise that there’s a choice to be made between these two women just because they were both neighbors of Handie’s and their behavior was juxtaposed. Mrs. Blooman and Mrs. Fine are both examples of extreme behavior, just in opposite directs. Mrs. Fine is too controlled and too controlling where Mrs. Blooman represents a lack of control and self-awareness. Neither trait is really appealing. While the two are represented as a comparison with a choice between them, neither of them makes an easy neighbor when taking as individuals. Between Neighbor A and Neighbor B, my preference is for Neighbor C, someone different and more moderate in their behavior. In this case, Neighbor C is really represented by Handie himself.

Handie does use some flattery and politeness to smooth things over with Mrs. Blooman, but what makes his behavior less manipulative than Mrs. Fine’s is that it contains no deception. Being honest doesn’t have to mean being rude and nasty, which is a concept that Mrs. Blooman struggles with. Handie is just honest about the things he finds appealing, emphasizing the positive, but he didn’t lie about what he finds positive about Mrs. Blooman. Mrs. Blooman also hasn’t made the connection that her own negative behavior provokes the negative interactions she has with other people, while Handie understands that positivity brings out more positive reactions in other people. Mrs. Fine has a sense of that as well because she knows that politeness and a smooth manner bring cooperation, but she doesn’t use that technique in an honest way. Handie makes business arrangements with Mrs. Blooman that suit his needs, but he’s honest about what he wants and what he has to offer her in the arrangements, and he follows through on his promises, which Mrs. Fine never does. Of course, Handie is the most balanced character in the story because he’s the one who is meant to demonstrate to Rainbow and young readers of the stories how to behave and how to get along with other people. He’s not entirely perfect because the author has established that he sometimes tries too hard, but he is meant to set a good example.

I’m pointing out Handie’s role as the good example to follow because I’ve noticed that many people tend to like “no filter” people, seeing them as the alternative to people who are a bit too smooth and manipulative, like Mrs. Fine. I think it’s important to realize that the Mrs. Bloomans and Mrs. Fines of the world are the extremes they actually are, and most of life isn’t about choosing between them. They both have their problems, and Mrs. Blooman only becomes a helper when she changes her behavior in response to the opportunity that Handie gave her. Handie is more the ideal, balanced person, someone who has control of himself and his responses to other people but not in a deceptive way. He uses his abilities to promote positive outcomes and considers the benefits to everyone involved rather than merely using people for his own purposes or taking out his frustrations on them. Life isn’t about picking between Team A or Team B any more than everyone is neither Neighbor A or Neighbor B. It’s about trying to be something better than either of the extremes and maybe bringing out the best of everyone.

Handie’s thoughts about marriage

I was amused by Handie’s thoughts on the subject of marriage, especially because he is a nineteen-year-old who has never been married, and he was delivering them to a woman who had evidently been married before. I don’t fault him for having thoughts on what he’s looking for in a wife, and I think a nineteen-year-old can have a sense of what other young men are looking for in a wife, but Mrs. Blooman is a Mrs. with a young son, after all. It’s not like she hasn’t had a man in her life before. Handie uses his thoughts about marriage to flatter Mrs. Blooman, in a way, by pointing out that there are positive qualities that a man might see in her, but I just think that she probably knows that since at least one man has married her in the past.

One of the striking parts of what Handie says about marriage is that a man wants a woman he feels would need him to protect her and take care of her, whereas he might feel that a woman who is strong and independent wouldn’t need him in her life. I can see that a person likes to feel that their partner needs them and that they have a definite role to play in the other person’s life. However, it did strike me as odd that Handie would characterize Mrs. Blooman’s level of capability as the major barrier to her remarrying.

As far as barriers to remarriage go in Mrs. Blooman’s life, there are far more obvious ones that Handie doesn’t mention. I considered whether or not Mrs. Blooman’s son might be a barrier to her remarriage. It’s debatable. Some men might be reluctant to commit to being an instant father, but on the other hand, there might be some men who would appreciate her son and also take it as a sign that they might have other children together. The biggest obstacles I can see for Mrs. Blooman come from herself and her own behavior. I think Handie doesn’t mention them because he’s trying to stick to promoting positives, but her temperament nature and lack of self-control are the first, most obvious aspects of her character that would make her difficult for another person to live with. Mrs. Blooman provokes other people with her bad behavior, lack of self-awareness, and lack of consideration for other people. She overcomes this by absorbing Handie’s emphasis on her positive qualities and changing her behavior to match his positivity and level of effort to put forth her best image, but she doesn’t change to become more dependent on him or any other man beyond her basic business arrangements. In fact, it’s her capability that gets Handie to make his business arrangement with her about meals for himself and Rainbow.

Farm wives have to be capable people because there are many jobs to be done on a farm, and everyone has a role to play. Like other farm wives, Mrs. Blooman has learned to cook and care for her house and her child. She has hired a man to work for her to help run the farm and manage the animals, but she’s still in charge as his employer. Even if Handie marries a woman to share his life on the farm and he sees himself as taking care of her by running the farm well, she will also have to do her part in taking care of the farm house, the cooking, any children they have, and possibly Handie himself during times when he might become sick or injured. Although the historical view would be that the man is the head of the household, providing for his family, the day-to-day reality is that everyone in the family is providing something for each other because everyone has a part to play. I know that, one day, Handie might well be grateful for a woman who will let him lean on her occasionally as well as her leaning on him because everyone needs someone to depend on for something. The image of a capable woman might sound like a modern one that evolved as more women started working outside the home or needing to work to provide an extra income, but women back then were workers as well, just not in a paid, official capacity, and their ability to do what they needed to do for their families was necessary. Handie might not be thinking about that right now because he is probably envisioning himself as the strong hero to the young woman of his dreams, but I think he might come to appreciate that aspect of a woman’s role in his life eventually.

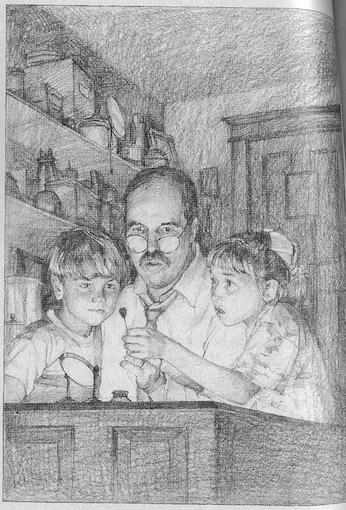

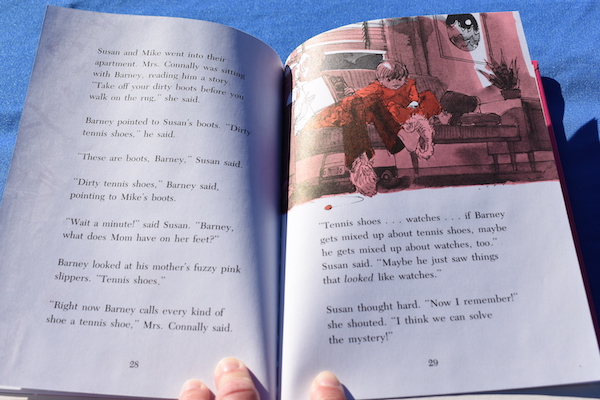

It’s 1851, and Professor Carver of Boston is living in an apartment above a candle shop with his wife and two children, his son Jamie and daughter Lorna. One day, a man named Mr. Giddings comes to see Professor Carver to request his help. For years, he has wanted to buy a particular farm with a beautiful house called Windy Hill. However, when he finally succeeded in buying the house and he and his wife went to live there, his wife became very upset. She said that she felt strange in the house and that she had seen a ghost. Now, she is too upset to return to Windy Hill. Mr. Giddings has heard that Professor Carver once helped a friend get rid of a ghost haunting his house, and he asks the professor if he would be willing to do the same for him.

It’s 1851, and Professor Carver of Boston is living in an apartment above a candle shop with his wife and two children, his son Jamie and daughter Lorna. One day, a man named Mr. Giddings comes to see Professor Carver to request his help. For years, he has wanted to buy a particular farm with a beautiful house called Windy Hill. However, when he finally succeeded in buying the house and he and his wife went to live there, his wife became very upset. She said that she felt strange in the house and that she had seen a ghost. Now, she is too upset to return to Windy Hill. Mr. Giddings has heard that Professor Carver once helped a friend get rid of a ghost haunting his house, and he asks the professor if he would be willing to do the same for him. Jamie and Lorna are thrilled by the house, which is much bigger than their apartment in town. They can each have their own room, and there is an old tower in the house that was built by a former owner, who was always paranoid about Indian (Native American) attacks (something which had never actually happened). However, their new neighbors are kind of strange. Stover, the handyman, warns them that the house is haunted and also tells them about another neighbor, Miss Miggie. Miss Miggie is an old woman who wanders around, all dressed in white, and likes to spy on people. There is also a boy named Bruno, who apparently can’t walk and often begs at the side of the road with his pet goat, and his father, Tench, who is often drunk and doesn’t want people to make friends with Bruno.

Jamie and Lorna are thrilled by the house, which is much bigger than their apartment in town. They can each have their own room, and there is an old tower in the house that was built by a former owner, who was always paranoid about Indian (Native American) attacks (something which had never actually happened). However, their new neighbors are kind of strange. Stover, the handyman, warns them that the house is haunted and also tells them about another neighbor, Miss Miggie. Miss Miggie is an old woman who wanders around, all dressed in white, and likes to spy on people. There is also a boy named Bruno, who apparently can’t walk and often begs at the side of the road with his pet goat, and his father, Tench, who is often drunk and doesn’t want people to make friends with Bruno. Then, strange things do start happening in the house. The quilt that Lorna has been making disappears and reappears in another room in the middle of the night. At first, the family thinks maybe she was walking in her sleep because she had done it before, when she was younger. However, there is someone who has been entering the house without the Carvers’ knowledge, and Jamie and Lorna set a trap that catches the mysterious “ghost.”

Then, strange things do start happening in the house. The quilt that Lorna has been making disappears and reappears in another room in the middle of the night. At first, the family thinks maybe she was walking in her sleep because she had done it before, when she was younger. However, there is someone who has been entering the house without the Carvers’ knowledge, and Jamie and Lorna set a trap that catches the mysterious “ghost.” Cranberry Autumn by Wende and Harry Devlin, 1993.

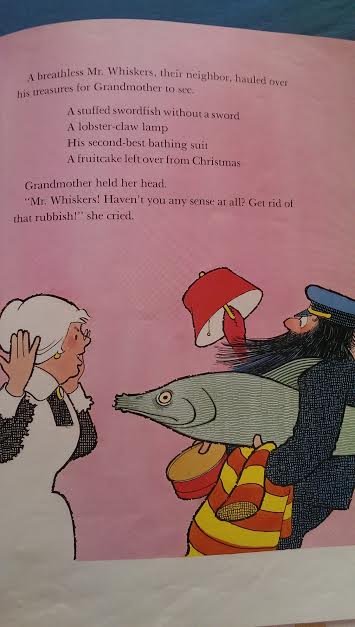

Cranberry Autumn by Wende and Harry Devlin, 1993. School is about to start, and Maggie and her grandmother realize that they’re short of money. Maggie needs new school clothes, and her grandmother needs a new coat. They know that some of their neighbors could also use some more money, so Grandmother suggests that they hold a sale. Some of them have some antiques and other interesting old items that they could sell.

School is about to start, and Maggie and her grandmother realize that they’re short of money. Maggie needs new school clothes, and her grandmother needs a new coat. They know that some of their neighbors could also use some more money, so Grandmother suggests that they hold a sale. Some of them have some antiques and other interesting old items that they could sell.