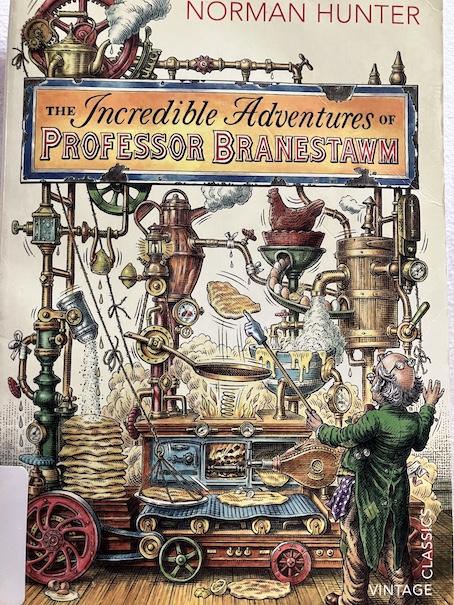

The Incredible Adventures of Professor Branestawm by Norman Hunter, 1933.

Professor Branestawm is a classic absent-minded professor. He’s is a balding man who wears several pairs of glasses, one of which is for finding the other pairs of glasses when he inevitably loses them. He’s a very clever man, but everyone knows that his inventions are likely to cause chaos. He’s not an easy person to talk to, so he doesn’t have many friends. His best friend is Colonel Dedshott, who is a very brave man.

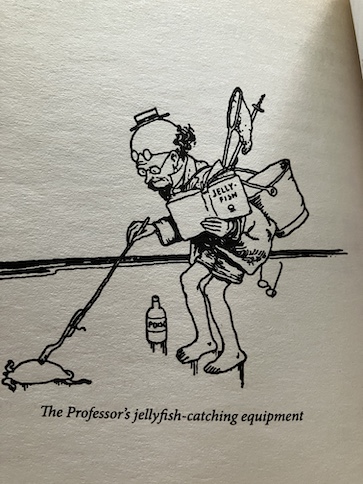

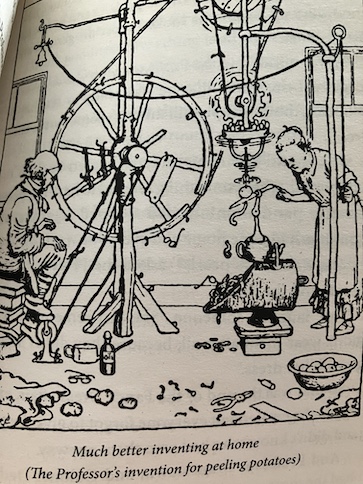

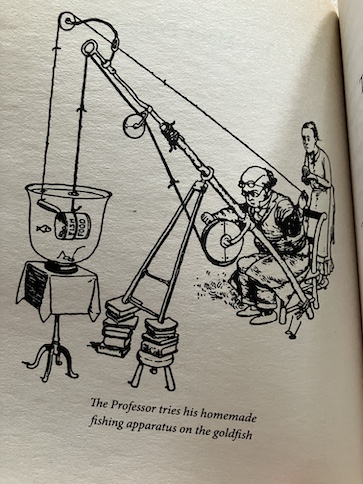

Every chapter in this book is about another of the Professor’s inventions and the adventures that the Professor, the Colonel, and the Professor’s housekeeper, Mrs. Flittersnoop, have with them and with various situations that the Professor creates with his absent-mindedness. The stories are accompanied by pen-and-ink drawings. I love the way almost every picture of the professor shows him shedding one or more of his many pairs of glasses and that the Colonel’s weapon of choice is a slingshot!

Chapter 1: The Professor Invents a Machine

One day, Professor Branestawm invites the Colonel to his house to see his latest invention, which he says will revolutionize travel. When the Colonel arrives, Professor Branestawm explains his idea. First, he points out that, if you’re traveling somewhere, you’ll arrive in half the amount of time you ordinarily would if you travel there twice as fast. The Colonel says that makes sense. Then, Professor Branestawm says that, the faster and faster you travel, the sooner you arrive at your destination. That also makes sense. Further, Professor Branestawm says, you eventually start traveling so fast that you arrive before you even start, and if you go fast enough, you can arrive years before you start. The Colonel doesn’t really understand this, but he takes the Professor’s word for it. The Professor has built a machine that will allow them to travel that fast, and the Colonel is eager to try it. He suggests that they try going back in time to a party he attended three years earlier. The Professor insists that they take some powerful bombs with them, just in case of emergencies (don’t try to make sense of it, there isn’t any), and the Colonel has his trusty catapult (slingshot) and bullets with him.

It turns out that, rather than going to the party three years earlier, they arrive at the scene of a battle that took place in another country two year earlier. Although they already know how the battle turned out, the Professor and Colonel can’t resist joining in with their bombs and catapult, and they end up wiping out an entire army and changing the result of the battle in favor of the revolutionaries. The revolutionaries are so grateful to them for their help that they take them to the palace of their former king, put the two men on the enormous throne there, and make them the new presidents of the country. Professor Branestawm realizes that they’ve made a terrible mistake and changed history because the king’s army was the one that was originally supposed to win the battle. The Colonel, however, doesn’t care because he thinks it sounds like fun to be a president and can’t wait to do some ruling.

Of course, the ruling of the two presidents doesn’t go well. Neither one of them really knows anything about running a country. Since they blew up all the country’s troops, there are no troops left for the Colonel to review, and he ends up playing with toy soldiers. Meanwhile, the Professor really just wants to get back to his inventing. Eventually, the revolutionaries get tired of this and tell them that they’ve decided that they don’t want any presidents, so they’re giving them a week’s notice before they’re out of a job. The Professor and the Colonel try not to take any notice (ha, ha) of the revolutionaries’ attempts to dethrone them. This just leads to the revolutionaries trying to imprison them in the dungeon, so the Professor and the Colonel are forced to escape in the Professor’s machine, which takes them back to the exact time and location where they started. They arrive just as the Professor’s housekeeper brings them some tea, so they have their tea, go about their usual business, and leave it to the historians to deal with the complications of the two of them changing history.

Chapter 2: The Wild Waste-Paper

When Professor Branestawm’s housekeeper puts a bottle of cough syrup with no stopper into the waste-paper basket, it accidentally creates a waste-paper monster! It turns out that it wasn’t really cough syrup in the bottle. It was a special life-giving formula that the professor invented. He only keeps it in a cough syrup bottle because cough syrup is the only thing that neutralizes the life-giving formula and stops it from bringing everything it touches to life, including the bottle holding it. Now that they’ve accidentally created a waste-paper monster, what can they do to stop it, especially since it seems to have the ability to use tools and is currently trying to saw down the tree where the Professor and his housekeeper are trying hide?

Chapter 3: The PRofessor Borrows a Book

Professor Branestawm accidentally loses a library book about lobsters, so he goes to another library to get the same book. By the time that he needs to return the library book, he has found the first one and lost the second one. For a while, he manages to avoid library fines by continually returning and checking out the same book from both libraries because the libraries don’t notice which library the book is from. Of course, he eventually loses the first book, too. He tries to fix the situation by getting the same book from a third library and then one from a fourth library, when he loses the third book. Where will it all end? How many libraries will have to share this one book, and where on earth are all these books about lobsters going?

Chapter 4: Burglars!

Professor Branestawm and his housekeeper go to the movies to see a documentary about brussels sprouts. (The housekeeper doesn’t care about brussels sprouts, but there’s a Mickey Mouse cartoon included with the feature, and she wants to see that.) When they get back, they discover that the house has been robbed! Professor Branestawm decides that he’s going to invent a burglar catcher, but the only burglar he catches is himself.

Chapter 5: The Screaming Clocks

Professor Branestawm’s clock stops, so he takes it to a clock repair shop. It turns out that the clock has only wound down because the Professor has forgotten to wind it. The Professor decides that he’s going to invent a clock that will go forever and never need winding. (This story is set before clocks that don’t need winding became common.) The Professor does invent a clock that will never stop and never need winding, but he makes a critical mistake: the chimes never reset after they strike twelve. They just continue counting up and up, endlessly, with no way to stop them! Just how many times will they endlessly strike before something terrible happens?

Chapter 6: The Fair at Pagwell Green

The Professor visits a local fair and invites the Colonel to join him. The Colonel ends up winning most of the prizes for the various games, and the Professor accidentally gets left behind in the waxworks exhibit, being mistaken for a wax statue of himself. When the Professor decides that it’s finally time to get up and go home, the people who work in the waxworks think that a wax statue has come to life!

Chapter 7: The Professor Sends an Invitation

Professor Branestawm writes a letter to the Colonel, inviting him to tea, but because he is distracted, thinking about potatoes, he accidentally writes a muddled letter and then mails the paper he used to blot the letter instead of the letter itself. The message that arrives at the Colonel’s house is a backward, muddled mess, and he has no idea who sent it to him. Since it looks like it’s written in some strange language he doesn’t know, the Colonel decides to take it to the Professor to see if he can decipher it. The Professor fails to recognize the letter as what he sent and has forgotten that he sent it. Will the two of them figure out what the letter is about, or will they eventually just give up and have some tea?

Chapter 8: The Professor Studies Spring Cleaning

Professor Branestawm’s housekeeper’s spring cleaning creates some chaos in the professor’s house, and the Colonel suggests that Professor Branetawm invent a spring cleaning machine. Predictably, the spring cleaning machine creates an even bigger mess and far more chaos.

Chapter 9: The T00-Many Professors

Professor Branestawm invents a very smelly liquid that brings things from pictures to life. The things from the pictures go back to being pictures when the liquid dries. Of course, there are some things that cause big problems when they’re brought to life. Possibly the most chaotic pictures that come to life are pictures of the Professor and the Colonel and the professor’s housekeeper. Who is who and which is which?

Chapter 10: The Professor Does a Broadcast

Professor Branestawm is invited to give a talk on the radio, and the Colonel helps him to rehearse. However, because he gets mixed up, he almost misses his own talk, and when he finally gives it, he speaks too fast and discovers that the time slot for his talk is much longer than he thought it was. Listeners are confused, but everything is more or less all right when the Children’s Hour comes on.

Chapter 11: Colonel Branestawm and Professor Dedshott

The Professor and the Colonel are going to a costume ball. Since the Professor doesn’t know what to do for a costume, the Colonel suggests that the two of them dress as each other. This causes some confusion, and neither of them likes each other’s clothes. The Professor’s social skills aren’t even great at the best of times, and the truth is that he’d rather be inventing things at home in his “inventory” (pronounced “invEnt – ory” as in a laboratory where you invent things, ha, ha). Then, the Countess at the ball raises the alarm that her pearls are missing! Everyone is confused when they try to get “the Colonel” to find the thief, and he doesn’t seem to know what he’s doing. It takes a while for things to get sorted out, but at least the Professor and the Colonel develop a new appreciation for being themselves instead of being each other.

Chapter 12: The Professor Moves House

Professor Branestawm’s house has gotten so full of his inventions that it’s become difficult to live there, so he’s decided to move to a new house. Moving to the new house is an escapade, and when Professor Branestawm and his housekeeper get there, they discover that the water and gas haven’t been connected up yet. Professor Branestawm’s attempts to remedy the situation render the new house unlivable, so he is forced to move back to his older house.

Chapter 13: Pancake Day at Great Pagwell

Professor Branestawm invites his friends and various members of the community to his house for a party, where there will be tea and pancakes. Everyone is happy to go because of the promise of pancakes, but when they’re all there, Professor Branestawm reveals that the party is to unveil is newest invention: a pancake-making machine! As the library man predicts, the pancake-making machine goes wrong (just like the Professor’s other inventions), but it’s all right because the town council comes up with a new purpose for it.

Chapter 14: Professor Branestawm’s Holiday

Professor Branestawm takes a trip to the seaside. He asks the Colonel to join him and bring his book about jellyfish, but unfortunately, he neglects to tell the Colonel where he’s staying (partly because he forgot where he was supposed to stay and is actually staying somewhere else). When the Colonel tries to find the Professor, he accidentally mistakes an entertainer dressed as a professor for Professor Branestawm. When the entertainer isn’t acting like himself (so the Colonel thinks), the Colonel becomes worried and decides medical intervention is necessary.

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive (multiple copies). It’s the first book in a series about Professor Branestawm, and it was also adapted for television multiple times.

My Reaction

Kids won’t learn anything about real science from Professor Branestawm, but the stories in the book are funny and not meant to be taken seriously at all. Most of the stories are about some pretty silly things that don’t really mean much in the end, but when you think about it, the Professor’s antics do lead to some pretty serious consequences, from wiping out an entire army just for the fun of it (pretty horrific in real life) and changing the course of history to accidentally blowing up someone’s house with his perpetually-chiming clock. No matter what the Professor does, though, there never seem to be any lasting consequences.

Even when people around him brace themselves for when the Professor’s latest project inevitably goes wrong, everybody still thinks that the Professor is pretty clever. The Colonel always thinks the Professor is clever, and even when he knows that the Professor is bound to do something that’s going to cause chaos, he enjoys the excitement. The housekeeper sometimes goes to stay with her sister, Aggie, when the chaos and excitement get too much for her.

The stories are just meant to be enjoyed for their zaniness, and there’s no point in analyzing them much. You don’t have to worry about whether anything the Professor does makes sense or exactly how he got any of his inventions to work. You can just enjoy seeing how everything develops and watch the craziness unfold! It sort of reminds me of Phineas and Ferb’s summer projects, which cause some chaos but are ultimately funny and always disappear at the end of the day. Enjoying these stories is what they used to say in the theme song for the tv show Mystery Science Theater 3000:

“If you’re wondering how he eats and breathes

And other science facts,

Just repeat to yourself “It’s just a show,

I should really just relax …”

I can promise you that, no matter what happens in any of the stories, the Professor and his friends will ultimately be fine and will probably have a cup of tea (or “a cup of something”) afterward. This book was originally published in Britain the early 1930s, and it was read by children during the Great Depression. I can imagine that it might have given children then a good laugh and some escapism during troubled times.

Strangely, at least one of the Professor’s inventions, the clock that never needs winding, is a real invention that we have every day because time has moved on (ha, ha) since this book was originally written and published. In fact, it’s very unusual to find clocks that need to be wound these days. Of course, the part about the clock perpetually chiming more and more and blowing up when it gets to be too much is just part of the craziness of Professor Branestawm.

Ten-year-old Kat is going to be living with her Aunt Jessie for the next year. Her parents are botanists, and they are spending a year in South America, studying rain forest plants. Aunt Jessie lives in a house in the same town as Kat and her parents so, by staying with her, Kat can continue going to the same school and see her friends.

Ten-year-old Kat is going to be living with her Aunt Jessie for the next year. Her parents are botanists, and they are spending a year in South America, studying rain forest plants. Aunt Jessie lives in a house in the same town as Kat and her parents so, by staying with her, Kat can continue going to the same school and see her friends.