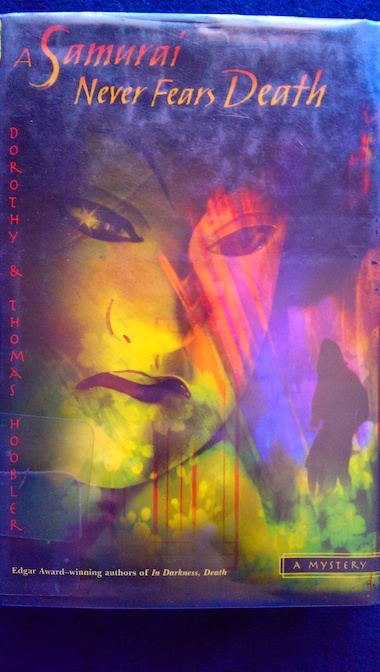

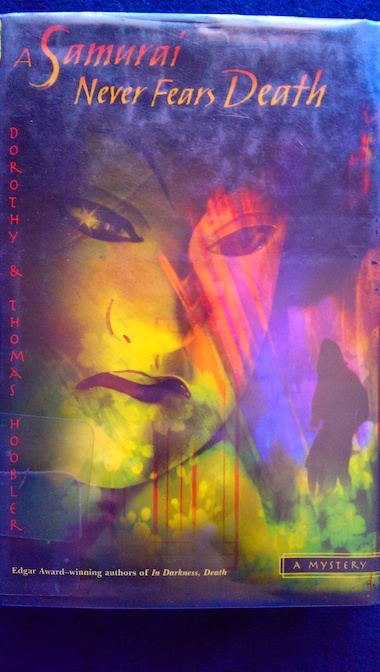

A Samurai Never Fears Death by Dorothy and Thomas Hoobler, 2007.

This book is part of the The Samurai Detective Series.

Sixteen-year-old Seikei returns home to visit his birth family in Osaka while Judge Ooka investigates reports of smugglers in the city. Seikei is a little nervous about seeing his birth family because he hasn’t gone to see them since he was adopted by Judge Ooka about two years before. All he knows is that his younger brother, Denzaburo, is helping his father to run the family’s tea business, which is probably a relief to Seikei’s father because Denzaburo was always more interested in the business than Seikei was.

However, things have changed in Seikei’s family since he left Osaka, and his homecoming isn’t quite what he imagined it would be. Seikei had expected that his older sister, Asako, might be married by now, but she says that Denzaburo is keeping her from her dowry because he needs her to help run the family business. Although Denzaburo enjoys business and the life of a merchant, it turns out that Asako has a better mind for it than he has. The two of them have been running the family’s tea shop by themselves because their father is ill. Also, although the family no longer lives above their shop, having bought a new house for themselves, Denzaburo says that he sometimes stays at the shop overnight to receive deliveries of goods. Seikei knows that can’t be true because no one ever delivers goods at night in Osaka. Denzaburo brushes off Seikei’s questions by suggesting that the three of them visit the puppet theater together to celebrate Seikei’s visit.

At the puppet theater, Seikei learns that Asako is in love with a young man who is an apprentice there, Ojoji. Because Ojoji is only an apprentice, the two of them cannot afford to get married, something that Denzaburo laughs about. However, before Seikei can give the matter more thought, they discover that one of the narrators of the plays has been murdered, strangled.

They summon an official from Osaka to investigate the scene, Judge Izumo, but Seikei isn’t satisfied with his investigation because it seems like Judge Izumo is quick to jump to conclusions. Then, suspicion falls on Ojoji. Asako doesn’t believe that the man she loves could commit murder and wants Seikei to ask Judge Ooka to intercede on Ojoji’s behalf, so Seikei begins to search for evidence that will help to prove Ojoji’s innocence.

The mysterious happenings and murders (there is another death before the book is over) at the puppet theater are connected to the smuggling case that Judge Ooka is investigating, and for Seikei, part of the solution hits uncomfortably close to home. However, I’d like to assure readers that Asako and her beloved get a happy ending.

During part of the story, Seikei struggles to understand how the villains, a group of bandits, seem to get so much support and admiration from other people in the community, including his brother. It is Asako who explains it to him. It’s partly about profit because the outlaws’ activities benefit others monetarily, but that’s only part of it. In Japan’s society, birth typically determines people’s roles in life, and each role in society comes with its own expectations about behavior, as Seikei himself well knows. Seikei is fortunate that circumstances allowed him to choose a different path when he didn’t feel comfortable in the role that his birth seemed to choose for him; he never really wanted to be a merchant in spite of being born into a merchant family. Others similarly do not feel completely comfortable with the standards that society has set for them, and their fascination with the outlaws is that the outlaws do not seem to care what society or anyone else thinks of them. The outlaws do exactly what they want, when they want to do it, dressing any way they please, acting any way they please, and taking anything they want to use for their own profit. Denzaburo, who was always willing to cut corners when it profited him, sees nothing wrong with this, and he envies the outlaws for taking this idea to greater lengths that he would ever dare to do himself.

The idea of throwing off all rules and living in complete freedom without having to consider anyone else, their ideas, their wants, their needs, can be appealing. Asako understands because, although she is better at business than either of her younger brothers, she cannot inherit the family’s tea business because she is a girl. She thinks that, because the system of society doesn’t look out for her interests, she has to look out for herself, and what does no harm and makes people happy (in the sense of giving them lots of money) shouldn’t be illegal. At first, Asako sees their activities as victimless crimes. Although she doesn’t use that term to describe it, it seems to be her attitude. However, do victimless crimes really exist? Seikei has a problem with this attitude because what the outlaws are doing has already caused harm in form of two deaths and the risk to Ojoji, who may take the blame for the deaths even though he is innocent. Asako might not care very much about the others at the puppet theater, but she does care about Ojoji.

It’s true that Seikei has defied the usual rules of society by becoming something other than what he was intended to be, and for a time, he struggles with the idea, comparing himself to the outlaws, who were also unhappy with their roles and wanted something different. However, the means that Seikei used to get what he wanted in life are different from the means that the outlaws use, and Seikei also realizes that his aspirations are very different from theirs. While Seikei had always admired the samurai for their ideals and sense of honor and order, the outlaws throw off the ideals of their society in the name of doing whatever they want. Although the outlaws do benefit some of the poorer members of society, paying money for goods that the makers might otherwise have to give to the upper classes as taxes and tribute and trying to stand up for abused children when they can because their leader was also abused as a child, their main focus is still on themselves and what they and their well-paying friends want. Seikei is concerned with justice and truth, which are among his highest ideals. Even though he learns early on that, as a samurai, he could claim responsibility for the deaths at the theater himself because, in their society, a samurai would have the legal authority to kill someone for an insult. Claiming responsibility for the killings would allow Ojoji to go free, and it would be one way to solve the problem quickly and make Asako happy, but Seikei cares too much about finding the truth behind the murders and bringing the real murderer to justice to take the easy way out. It is this difference in ideals and priorities between Seikei and others around him which set them on different paths in life.

One thought that seemed particularly poignant to me in the story is when Seikei reflects that we don’t always understand the importance of the choices we make in life at the time when we have to make them because we don’t fully understand all the ways in which a single choice can affect our lives. He thinks this when the leader of the outlaws offers to let a boy who was abused come with them and join their group after they intervene in a beating that the boy’s father was giving him. They tell him that joining their group would mean that he could do whatever he wants from now on. The boy, not being sure who they are or what joining their group would really mean for him, chooses to stay with his father. Seikei wonders then whether the boy will later regret his decision or not. His father obviously doesn’t treat him well and may not truly appreciate his show of loyalty by remaining, although joining the outlaws comes with its own risks. It’s difficult to say exactly which two fates the boy was really choosing between in the long run and which would be likely to give him a longer, happier life, which is probably why the boy chose to stick with what he already knew.

There is quite a lot in this story that can cause debates about the nature of law and order, society’s expectations, and the effects of crime on society and innocent bystanders. I also found Seikei’s thoughts about what makes different people choose different paths in life fascinating. I’ve often thought that what choices a person makes in life are determined about half and half between a person’s basic nature and the circumstances in which people find themselves, but how much you think that or whether you give more weight to a person’s character vs. a person’s circumstances may also make a difference.

The story also explains what fugu is, and there is kind of a side plot in which Judge Ooka wants to try some. A lot of the characters think that the risk involved in eating the stuff isn’t worth it, but well, a samurai never fears death, right?

There is a section in the back with historical information, explaining more about 18th century Japan and the style of puppet theaters called ningyo joruri, where unlike with marionettes or hand puppets, the puppeteers are on stage with the puppets themselves, wearing black garments with hoods so that the audience will disregard their presence (except for very well-known puppeteers, who might reveal their faces). For another book that also involves this style of puppetry, see The Master Puppeteer.

The Master Puppeteer by Katherine Paterson, 1975.

The Master Puppeteer by Katherine Paterson, 1975. Okada was once Yoshida’s teacher, and he accepts Jiro into the theater. Jiro is fascinated with the world of the theater, studying alongside Yoshida’s son, Kinshi, who becomes his closest friend. However, he must first graduate from apprentice to puppeteer before he can begin earning enough money to support his family, and the news from outside the theater is grim. Word has reached him that his father is ill and his mother is starving. The poor people of Osaka, starving and oppressed by the wealthy merchants and tax collectors, begin rioting.

Okada was once Yoshida’s teacher, and he accepts Jiro into the theater. Jiro is fascinated with the world of the theater, studying alongside Yoshida’s son, Kinshi, who becomes his closest friend. However, he must first graduate from apprentice to puppeteer before he can begin earning enough money to support his family, and the news from outside the theater is grim. Word has reached him that his father is ill and his mother is starving. The poor people of Osaka, starving and oppressed by the wealthy merchants and tax collectors, begin rioting.