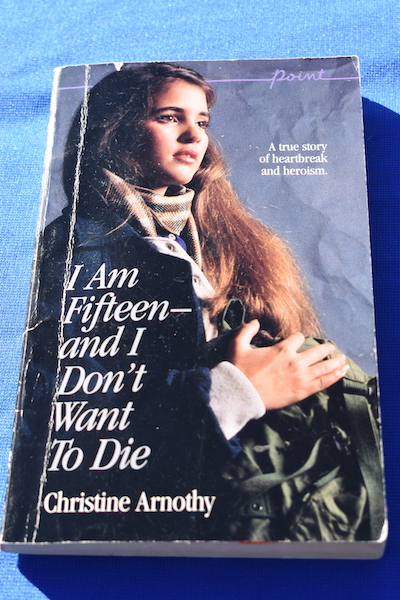

I Am Fifteen – And I Don’t Want to Die by Christine Arnothy, 1956.

Christine Arnothy was a fifteen-year-old girl during the siege of Budapest during World War II. In this book, she recounts her memories of that time, based on diaries that she kept. Following the war, she worked in a bookstore in Belgium before writing her memoirs. This book was awarded the Prix de Verities, which is a French prize for nonfiction.

When the book begins, Christine and her parents are hiding in a cellar during the siege of Budapest along with their neighbors. It is difficult for them to keep track of the time because they must remain in the cellar and limit lights that could give their location away. After living in such cramped quarters for many days, everyone is getting on everyone else’s nerves. They quarrel over scarce resources and hoard things for their own families, worried that their neighbors will take too much.

For a time, a young ex-soldier they call Pista (although he has another name) comes to stay with them, and he goes out to scavenge goods for them from ruined parts of the city. While he does this, it raises their spirits and hopes for survival. Unfortunately, death is all around them, and Pista is eventually killed by a mine. There are scenes in this book that would make it frightening and disturbing for young readers. Christine is fearful for her own life, worried that she will die in the cellar that has been their shelter.

When the German and Russian soldiers arrive, there is more slaughter. Eventually, Christine and her family are able to get out of the city and go to the villa where they had originally hoped to go to escape the bombings. They had already stocked the villa with provisions and were allowing some refugee friends of theirs to use it. When they arrive, they discover that their “friends,” believing that they were killed in the bombings, have appropriated their belongings and actually seem disappointed to find that they are alive and want some of the provisions that are left. Christine reflects on how quickly morals and ethics can be put aside in wartime. Their supposed “friends” are not so friendly when resources are scarce and their deaths would have meant that they could keep more for themselves.

Transportation has been disrupted, but they are finally able to board a train to get to a small house they own in the countryside. They remain there for three years before deciding that they need to leave entirely.

I found the story difficult to read because of all the sad and gruesome parts, but I found it interesting that Christine reflects that the part of her that died in the cellar in Budapest was the child that she used to be. At the end of the story, she realizes that she has become an adult and, although she is worried about the life that she may be heading for, she is ready for a new life.

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive (multiple copies).

Silver Days by Sonia Levitin, 1989.

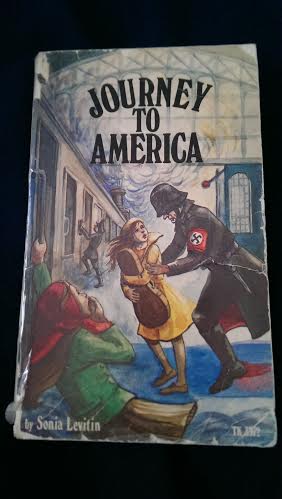

Silver Days by Sonia Levitin, 1989. Journey to America by Sonia Levitin, 1970.

Journey to America by Sonia Levitin, 1970. But, getting on the train out of Germany is only the first step of their long journey. Lisa and her mother and sisters live as refugees in Switzerland, waiting for her father to help arrange for their passage to America. Often, they have too little to eat because they don’t have much money. There are some people who help them, and they make some new friends, but the long wait is difficult. Meanwhile, they must face the frightening events taking shape around them, around the people they left behind, and their own uncertain future.

But, getting on the train out of Germany is only the first step of their long journey. Lisa and her mother and sisters live as refugees in Switzerland, waiting for her father to help arrange for their passage to America. Often, they have too little to eat because they don’t have much money. There are some people who help them, and they make some new friends, but the long wait is difficult. Meanwhile, they must face the frightening events taking shape around them, around the people they left behind, and their own uncertain future. The Night Crossing by Karen Ackerman, 1994.

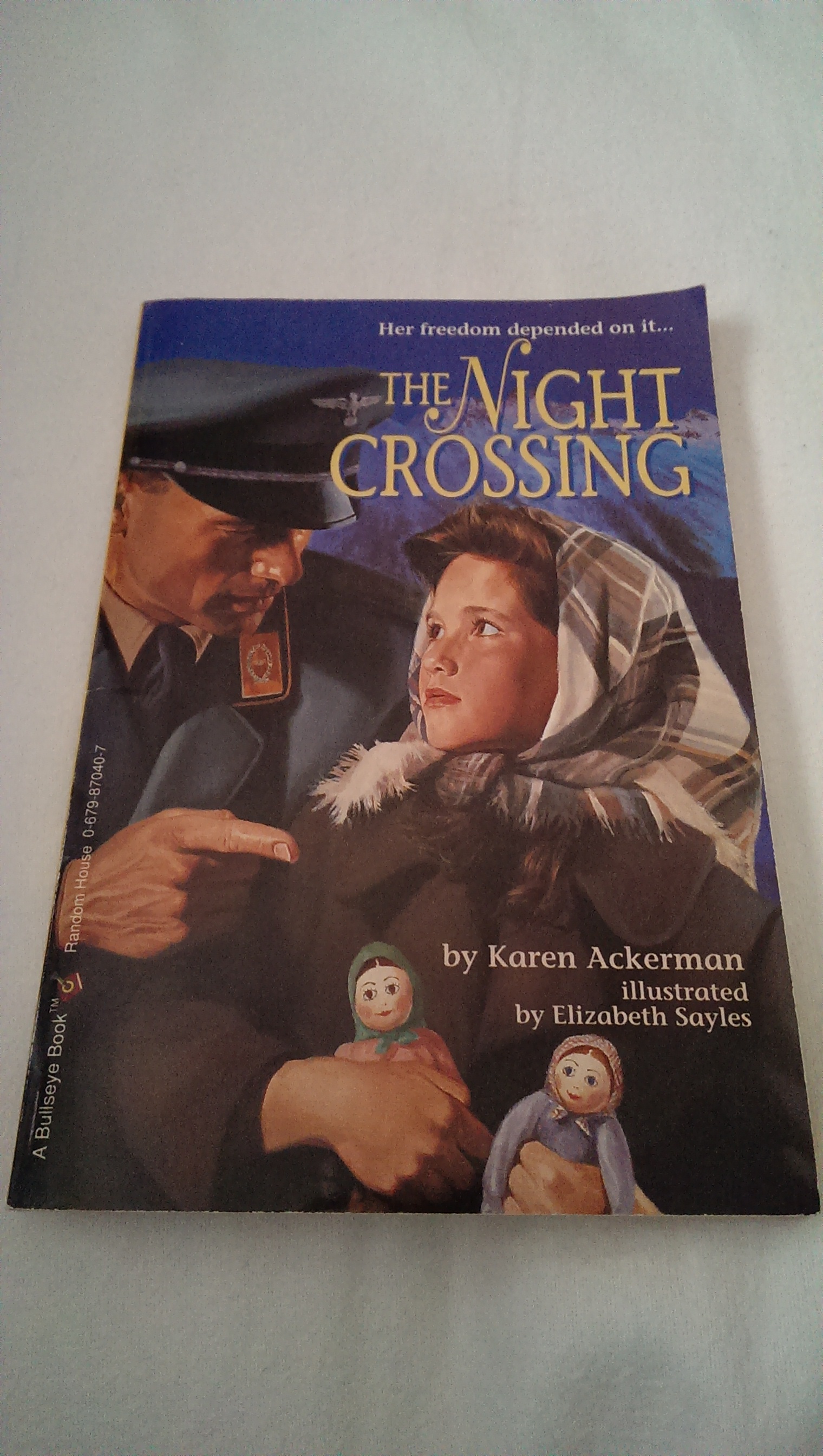

The Night Crossing by Karen Ackerman, 1994. This is a pretty short chapter book. Although the subject matter is serious, and parts might be frightening to young children (the part where Clara and Marta are chased and perhaps some of the parts where the family is hiding), there are only vague references to more dark subjects like concentration camps (people who already know what they are and what happened there would understand, but children who haven’t heard about them wouldn’t get the full picture from the brief mentions). The book would be a good, short introduction to the topic of the Holocaust by putting it in terms of the way it changed the lives of ordinary people who had to flee from it. Actually, it wouldn’t be a bad way to start a discussion of the Syrian refugees in Europe by putting it into the context of ordinary people fleeing the violence of war.

This is a pretty short chapter book. Although the subject matter is serious, and parts might be frightening to young children (the part where Clara and Marta are chased and perhaps some of the parts where the family is hiding), there are only vague references to more dark subjects like concentration camps (people who already know what they are and what happened there would understand, but children who haven’t heard about them wouldn’t get the full picture from the brief mentions). The book would be a good, short introduction to the topic of the Holocaust by putting it in terms of the way it changed the lives of ordinary people who had to flee from it. Actually, it wouldn’t be a bad way to start a discussion of the Syrian refugees in Europe by putting it into the context of ordinary people fleeing the violence of war.