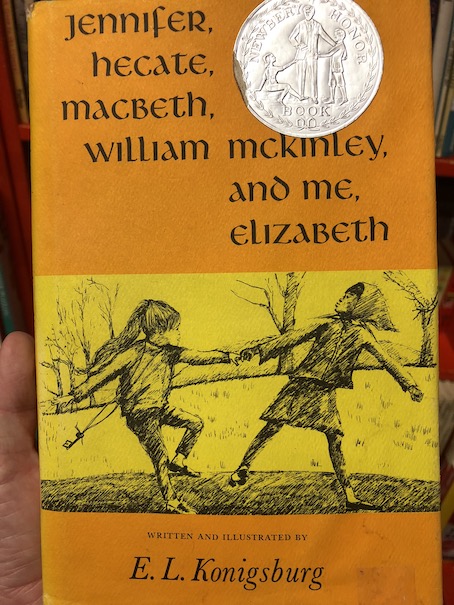

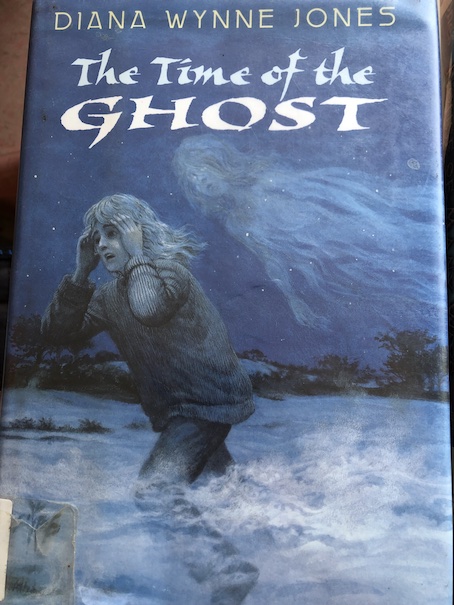

The Time of the Ghost by Diana Wynne Jones, 1981.

This isn’t a very long book, but it packs a lot in! This is both a time travel story and a supernatural ghost story, but with the odd twist that we don’t initially know who the “ghost” is, and she isn’t really dead. She’s trying to save her own life.

In the beginning, although this book is from the first person perspective, we don’t know quite who the narrator is. Even the narrator isn’t quite sure who she is or what has happened. Her last memory is that there was some sort of accident, and her mind doesn’t seem to be working right. Now, she seems to be walking through the countryside, but she can’t remember what happened earlier that day or even what she had for lunch. When she looks down to see what she’s wearing that day, she realizes in a panic that she can’t see herself. She has become a ghost!

It takes her some time to get her panicked thoughts together, but she gradually begins to recognize the countryside. She is surprised that she can look over a hedge, thinking that it was something she had always wanted to do before, and she must have grown. There is a small hut nearby, and she recalls that there is an old rag doll called Monigan inside. Exploring further, she finds herself at a school and locates a classroom she recognizes. To her surprise, she discovers that it’s a Latin class full of boys, and although she has no body, she is sure that she’s a girl, so this can’t be her class. However, she does recognize the teacher as someone familiar but also intimidating.

Leaving the classroom, she continues exploring the school, and she finds people she is sure are her family. She remembers that the woman is called Phyllis, and Phyllis is her mother. There are also girls called Imogen, Fenella, and Charlotte. The ghost thinks that these are her sisters and that her name is Sally because Phyllis seems to call her Sally, although nobody really seems to see her. Sometimes, people just seem to have a sense that someone is there, and the dog, Oliver, seems to know she’s there. Pieces of information click in the ghost’s mind. This family’s last name is Melford. The teacher in the Latin class is her father. Sally is short for Selina. Charlotte is called Cart as a nickname.

The ghost finds herself angry and hating her family. She wonders if she could have died in the accident she vaguely remembers and if she came back to get some sort of revenge on her family, but the idea horrifies her, and she’s sure that she wouldn’t have thought of it in other circumstances.

The ghost watches as Fenella goes to the little hut and pretends to worship the doll Monigan and call her forth, like the doll is some kind of oracle. The ghost remembers that Cart was the one who started this game a year before and that she always thought that it was a boring game. Cart started the game because the four sisters had been fighting over the doll or playing with it too roughly one day, and they had each grabbed an arm or leg and pulled the doll apart. Cart had felt guilty about that, so she sewed the doll back together (badly, because she’s bad at sewing), and she turned the doll into a kind of oracle that the girls would worship to make it up to the doll that she had been ruined. Now, the doll is moldy and mildewy from being left in the little hut for a year. Only little Fenella still plays this game, although the doll has never actually done anything magical when they’ve called on her.

Gradually, the ghost begins putting the pieces of her memories together. Her parents manage a boarding school for boys. The girls help out with chores at the school, but they’re mostly expected to stay out of the way. Although they attend a different school themselves, it feels like they never get a break from school because they live at one. They never even get summers off because there are summer courses for disabled children at the boarding school.

Sally the ghost listens to her sisters complaining about her in her absence. They resent her for being overly sweet and a perfectionist and for defending their parents when the other girls criticize them. Sally is angry with them for the things they say behind her back and for their constant bickering and drama. Imogen gets melodramatic and picks at her sisters because she’s worried about not achieving the music career she really wants. Cart keeps trying to shut Imogen down because she feels overwhelmed by sentiment and emotions, and admittedly, Imogen’s emotions are frequently overwhelming. This dynamic between Imogen trying to express her overwhelming emotions and Cart trying to shut her down is a large part of the quarreling between the girls. Fenella, the youngest of the sisters, is just being a silly little girl, and she is rather fed up with her older sisters. At one point, Sally finds a poem that Fenella wrote that explains her relationship with her sisters:

“I have three ugly sisters

They really should be misters

They shout and scream and play the piano

I can never do anything I want.”

It’s a pretty accurate description of what goes on in their house. All of the girls are loud and argumentative, and a large part of the tension in their house comes from the inability of any of them to do what they want to do. Sally notices some pictures on the walls and remembers their father (whom the girls only refer to as “Himself”, never as “father” or “dad”) yelling at them and calling them “bitches” for stealing art supplies from the school for drawing and painting. Imogen’s drama about her music career is because she’s not allowed to use the music room at the school for practicing, and she thinks that she’ll never get a chance to develop her abilities. The parents pay more attention to the students at the school than they do to their own daughters, even forgetting to leave the girls any supper sometimes. The girls’ home life is not happy, and that’s why they’re not happy with each other. The two oldest girls especially are not happy with their parents because of their neglect.

As Sally listens to her sisters talking about her, Cart and Imogen admit that they’re both jealous of Sally because she gets to be somewhere else that will be important to her future career. Sally wishes that they would say where she’s supposed to be because she can’t remember. She finds a few unfinished rough drafts of letters that she wrote to her parents, trying to tell them that life at the school didn’t have much to offer her and that she was going away, but Sally can’t imagine where she would have gone. One of the letters even says that her life is in danger, but from what?

There is a bright spot in the girls’ lives, and that’s a secret friendship they’ve developed with some of the boys at school. The boys visit them in the kitchen after dinner, and they have coffee together. As ghostly Sally watches one of these visits, the boys ask the girls what happened to Sally, which ghostly Sally is (literally) dying to hear. Sally’s sisters explain that Sally’s disappearance is part of a Plan the girls have.

It’s obvious that the girls’ parents neglect them. While Sally has always been defending their parents to the other girls, the other girls want to prove to her that their parents would never notice if something awful happened to one of them. A lot of the strange things that Sally has witnessed them doing that day are part of this Plan. Fenella has been going around the entire day with big knots tied in her hair, and their parents haven’t noticed. Fenella says that if they continue to not notice, she’ll act like she’s fallen seriously ill. Sally’s sisters say that Sally has gone to stay with a friend named Audrey Chambers, but their parents don’t know and still haven’t noticed that she’s even gone.

The sisters and the boys decide to try holding a seance for fun, and ghostly Sally uses this as an opportunity to communicate with them. Although she has some difficulty and misspells her message, she manages to convince Imogen that she’s the one communicating and that she’s dead. Imogen gets hysterical, but the others calm her down by phoning her friend’s house and confirming that Sally is there and that she’s fine. Ghostly Sally can’t understand it. She’s sure that she’s really Sally, but how can that be if Sally is definitely at her friend’s house?

Ghostly Sally seeks out living Sally, and to her surprise, she finds her, although she feels disconnected from this girl. She also learns that this Sally has been secretly doing things with a boy from the school, Julian, performing nighttime rituals with the doll, Monigan. Although ghostly Sally remembers having been friends with Julian, seeing him from outside herself makes her realize that Julian is actually sinister and disturbed. In her spirit form, she also realizes that their rituals with Monigan have stirred up something genuinely supernatural, apart from herself.

As things become more clear to her, the ghost begins to think that she was wrong about being Sally. She is still sure that she is one of the four sisters, neglected at her parents’ school, but she doesn’t think that she’s Sally after all, and that’s why she had no knowledge of Sally’s secret rituals with Julian and couldn’t remember where Sally was or what she was thinking. She also realizes that everything she has seen happened when she was younger. Somehow, after her accident, her spirit went back into the past, seeing things that she and her sisters used to do.

As the “ghost” wakes up in the hospital in the present day, she also realizes that she is not actually dead. She’s been having an out-of-body experience. Worse, her “accident” wasn’t really an accident. Someone tried to kill her. Julian, also older now in the present day, shoved her out of his car while they were driving somewhere. He was deliberately trying to kill her! Something that happened during that time in the past, during the time with the Monigan rituals and the girls’ Plan to confront their parents over their neglect led up to this attempted murder.

The “ghost” still can’t remember everything that happened in the seven years since then, leading up to the attempted murder, and she’s still confused about who she really is. She only senses that Monigan tried to kill her through Julian. Although the girls once thought that Monigan was just a game, Monigan is actually a real, evil spirit. Seven years ago, Monigan told them that it would claim a life, and now, Monigan is trying to do so. Can the “ghost” regain her memories and figure out what to do in time to save her life before the next attempt?

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive (multiple copies).

My Reaction

Earlier, I covered The Headless Cupid, in which children play at being witches and doing magical rituals that are clearly nonsense, but this book has children who are coerced by some ancient supernatural spirit into doing “real” occult rituals. The children’s rituals involve blood and cruelty to animals, which I didn’t like when I was reading the story. We don’t fully get to know what Monigan actually is, although there are indications that Monigan might be some kind of ancient goddess that craves sacrifices, especially human sacrifices. Monigan seems to remember receiving sacrifices before, in the distant past. Although Cart thinks that she invented Monigan, that Monigan is just a doll they tore, and that all of their rituals are just playacting, the “ghost” realizes that they were all being manipulated by the spirit called Monigan into thinking that. Monigan took advantage of the neglected children and their mentally ill friend for its own purposes. I think Monigan was based on Morrigan from Irish mythology. We are told in the story that this British boarding school is built on a site that has been inhabited from ancient times, and the girls’ father is obsessed with the archaeology of the area, which may also be responsible for stirring up this ancient spirit.

The intriguing part of this story is first that the readers aren’t sure whether or not the “ghost” is actually dead, and then, the readers as well as the ghost have to determine the ghost’s true identity. At first, the “ghost” thinks that she knows who she is, but then, she thinks that she was wrong. (Or was she?) Even when she is awake in the present day, her mind is still confused, and even two of her sisters, while they know that Julian’s attempt to kill her was part of Monigan’s curse, find it difficult to remember everything that happened when all of this started. The “ghost” has to go through the events of the past, with Monigan working against her all the time, to figure out what set off this threat against her before she runs out of time. She knows that Monigan plans to kill her before the day is over, and she doesn’t have much time left to break this curse or prevent it from happening in the first place. The “ghost” isn’t sure at first that she can change the past, but she gradually manages to get through to the other children and figure out a solution with the help of her sisters.

I found the parents in the story not just neglectful but actually cruel and infuriating. The father keeps calling his daughters “bitches” when he gets angry at them. When the girls appeal to their mother about how they’re not being fed and have to keep begging food from the school’s kitchen, the mother shuts her eyes and tells them to stop bothering the cook. The cook is also revealed to be stealing food from the kitchen herself, which may be the reason why both the girls and the students have little to eat, but when the girls tell their mother about it, their mother doesn’t want to hear about it. She just doesn’t want to go to the bother of finding another cook. I’m amazed that the girls haven’t actually died at some point before this or that social services hasn’t gotten involved. The girls do attend a different school from the one their parents manage, so they would have the opportunity to get help and attention from an outside source.

At one point, Fenella openly tells her mother that she’s neglecting them while she only pays attention to the boys at the school, and her mother says that girls can look after themselves while boys can’t. It’s like her mother looks at the girls like some people look at pet cats when they just let them roam and hunt for their own food. I don’t even approve of people neglecting their cats, like they don’t even have pets so much as a nodding acquaintance with feral animals. Even in the present day, when our “ghost” lies in a hospital bed after a murder attempt, their mother doesn’t come to see her because she’s too busy helping the boys at the school to pack their trunks. The father is openly hostile to his daughters, and the mother doesn’t seem to have any feeling or concern for them at all.

The concept of the book was interesting, but it’s not one that I would care to read again because I found it dark and frustrating, although it does end well. Things do improve for the girls in the past after their father discovers their weird rituals and sends them off to their grandmother’s house, angrily declaring that he never wants to see any of them again. The father’s rejection of them is actually a blessing. At their grandmother’s house, they get regular food and the attention that they desperately need. The mother partly redeems herself at the end of the book by coming to see her daughter after all, saying that she felt obligated to get the boys all packed but now that’s done, so she is free to stay with her daughter until she’s fully recovered. The girl does recover, and she begins reconciling herself to her past traumas, both the supernatural ones and the ones resulting from her parents’ neglect and her tumultuous relationship with her sisters.

One thing that the “ghost” accomplishes is that she gets a look at her past and herself as they really are, viewing herself and everything that happened from a neutral position as the “ghost.” Seeing herself from the position of a third person, she discovers that she doesn’t like the things she’s done or the person she’s been during these last several years. That’s why she has felt so disconnected from herself and her memories and why she couldn’t even recognize herself or the things she did in the past. The “ghost” is so upset with herself and ashamed of her life choices that she wonders if she’s really worth saving from Monigan. Fortunately, her sisters truly love her and know that she’s worth saving. Their bad choices and poor behavior to each other have been largely the result of their parents’ neglect, a trauma they all share and understand. Although the ghost doesn’t remember everything at first, the other sisters know that, after they went to live with their grandmother and received the attention and care they really needed, they all improved and their relationships with each other improved. They’ve been trying to move on from their past ever since, and they need to settle the matter about Monigan once and for all to truly be free to go forward in their lives. One of the sisters knows exactly what kind of sacrifice will finally appease Monigan and save her sister’s life.

Monigan wants something perfect as a sacrifice, but our “ghost” isn’t a perfect person. Nobody is perfect, and our “ghost” has become truly aware of her flaws and the nature of her troubled past through her out-of-body experiences. However, things can be perfect in someone’s imagination, and one of the sisters has a more powerful imagination than the others. Someone has a dream that is perfect, at least in her mind. When she gives Monigan that dream, she not only frees her sister from Monigan but herself from something that her future self has realized that she doesn’t really want. Both she and her sister have been clinging to things that were harmful to both of them, making them into the kind of people neither of them really wanted to be. It was their insecurity from their parents’ neglect that made them cling to things that they thought would make them special and distinct. Once they are free from these harmful influences, not only does Monigan stop trying to take their lives, but they are truly free for the first time to become something better. Monigan does claim one life at the end of the story, but in that case, it’s only justice.