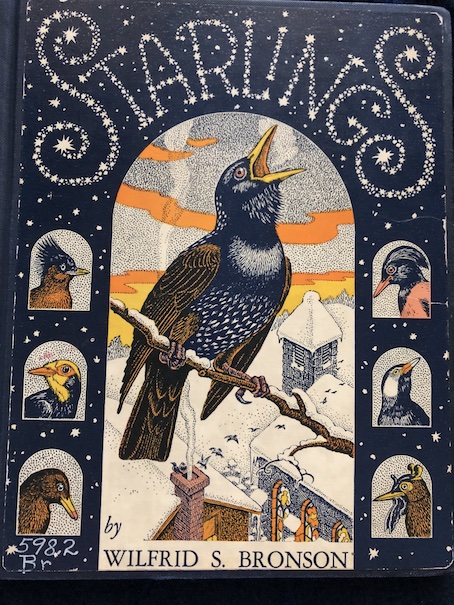

Starlings by Wilfred S. Bronson, 1948.

The title of the book tells you what it’s about; this is a children’s picture book about starlings. That sounds pretty straight-forward and even a little dull, but there is more to learn about starlings than I imagined, and the author of this book has an imaginative way of explaining information. I love books that cover odd topics in detail, and I enjoyed the whimsical quality of this book. The pictures are detailed black-and-white drawings, some with captions like comics. Most of them explain the anatomy of the birds or their habits, but they have some unique ways of expressing educational information.

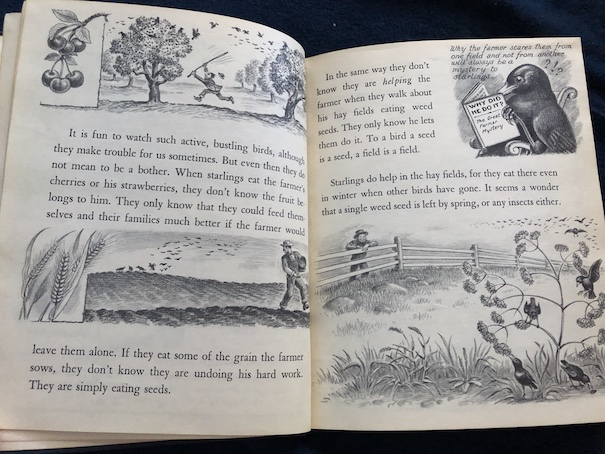

The book begins by describing the singing of starlings and then explains how farmers view starlings. Starlings can be a pest to farmers when they eat their fruit or the seeds the farmers are trying to plant, but they can also be helpful when they eat weed seeds and prevent weeds from coming up in the farmers’ fields. Of course, the birds don’t know when they’re helping or hindering because, as far as they’re concerned, they’re just there to eat any food that happens to be available at the moment. I like the little picture of the bird reading a mystery book, trying to figure out why farmers don’t mind when they eat some seeds and try to scare them away from others. That’s an example of the whimsy I was talking about.

The book continues describing what starlings eat and places where they like to roost, and it explains how they affect people living in cities (mainly, messing up their cars). There were times when people in cities considered them such a nuisance that they would shoot them, and some poor people hunted them for food. Actually, the entire reason why we have starlings in the US is that people over-hunted other types of birds (there is a disturbing picture of hunters with piles of dead birds at one point in the book), and birds are an important part of the ecosystem. Even though they can annoy farmers when they eat seeds and fruit, they also eat bugs that are pests to crops.

I was really struck by the passage that explained how starlings were first brought to the United States and why they were brought here:

“Some people think that starlings have no right to food or nesting-places because they are not ‘American birds.’ Yet all the starlings you see were born in America. So were their parents and grandparents and great-great-grandparents and all their relatives clear back to 1890. In that year their ancestors were caught in Europe and brought in cages to America. So many American birds had been killed at that time by our own ancestors that our crops were growing wormier and wormier each year, while insect pests grew worse and worse. So starlings were imported to help us fight the insects. They were freed in Central Park in New York City and left to look out for themselves.”

This explanation uses simplified language for children, and it also oddly evokes imagery of human beings. We don’t normally refer to animals as “foreigners” because animals don’t speak different human languages or have allegiances to foreign governments like people from other countries do. When we talk about new species that have been introduced to an environment where they did not originally belong and quickly spread out and multiple, we usually call them “invasive species.” In that case, the ecological concern is that the new invasive species will disrupt the balance of the natural environment and crowd out native species, but the author is trying to point out that the situation with the starlings was different. The starlings were introduced to the environment in the US on purpose, not by accident, and it was done specifically because they were meant to a solution to a problem. The environment had already been disrupted by humans who had moved into areas where they had not lived previously and where they killed too many of the native species themselves without regard to what that would do to the natural environment and their own farming. The introduction of the starlings was meant to restore a balance that had been lost. However, the people who had originally caused the problem didn’t see it that way, seeing the starlings as pests because they were “foreign.” While birds in general may occasionally be a nuisance because they don’t understand human priorities, they still perform useful functions for human beings as they go about their lives, just being the birds they are – eating annoying weed seeds and bugs and scavenging food from what humans throw out.

“People who think that starlings should be starvelings because they are ‘foreigners’ should remember that these American-born birds save much of what they themselves throw away and are still helping us to fight insects as they did in 1890.”

I understand what the author is trying to explain about balance in the ecological system, but I was struck by the human imagery that the passage evokes: “Foreigners” who came to New York City, not unlike immigrants fresh off the boat from Ellis Island during the 19th century, set free to make their way in a strange environment among people who often regarded them as worthless pests, disliking them while still using the useful services they provided. The comparison still fascinates me. At first, I wasn’t sure that the author meant to make that broader comparison here. I thought he probably used that language just to simply the ecological concepts for children’s understanding, but the author does make another comparison a little further on:

“So let’s be fair. If American-born starlings are foreigners, then so are all people in America except the Indians (Native Americans). So are many kinds of birds, animals, and plants. Our ancestors brought them here from other countries. But if all these creatures, and ourselves, are American now, then so are the starlings. Yes indeed!”

So get off your high horse, starling-haters.

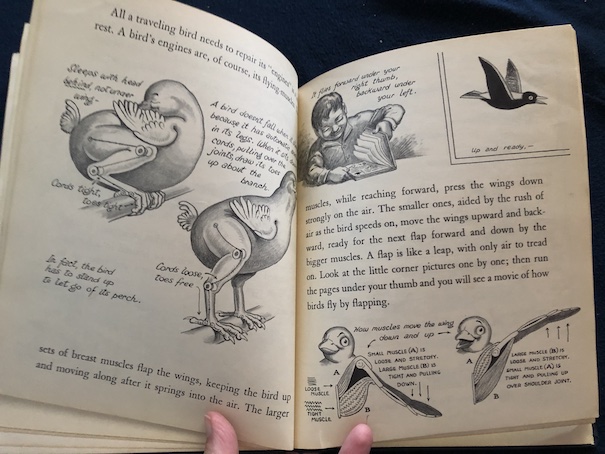

At several points in the book, the author compares birds to airplanes, explaining their muscles and flying mechanisms like machinery. I liked the page where the author compares different planes and helicopters to types of birds (cruisers being like gliding eagles and albatrosses, fast-turning speed planes like starlings and swallows, and hovering helicopters like humming birds). The parts that describe how birds cling to branches as they sleep and how their wings move look accurate and helpful. The part about how a bird creates eggs is hilarious. The text about the formation of the egg inside the bird isn’t bad. It completely skips over the subject of the fertilization of eggs (understandably), and the picture show the bird as a kind of egg-making factory with little men assembling the parts of the egg in stages instead of showing a bird’s reproductive anatomy.

In the upper right corners of this section of the book, there are little squares with a flying bird because part of the book is meant to be uses as a flip book to see a bird flying. The page shown above with the boy flipping through the book shows how to use the flip book portion.

There is a section of the book that explains how baby birds develop in the egg and eventually hatch.

There is also a section in the book that shows how adult starlings will prepare a nest for their eggs and how they raise their babies.

As I was reading the book, I wondered who the author, Wilfred S. Bronson, was. Bronson was an artist specializing in natural history, and he wrote and illustrated other books for children about animals and natural history. In the years before he wrote this particular book, he served in the US Army during World War I and painted murals for the Works Progress Administration (WPA) during the Great Depression. He also participated in expeditions to gather specimens and create illustrations of wildlife for botanical gardens and museums.

I haven’t found a copy of this particular book to read online, but it was republished in 2008 and is still available from Amazon.