The Christmas Tree Mystery by Wylly Folk St. John, 1969.

A couple of days before Christmas, twelve-year-old Beth comes running to her 10-year-old sister Maggie, saying that she’s in trouble and needs her help. Beth doesn’t know whether Maggie can help at all, but she thinks she’s done something wrong and needs somebody to listen to her. Someone stole the family’s Christmas tree ornaments the day before, and Beth saw someone running out of their backyard right after the theft. She was sure that the person she saw was Pete Abel, and that’s what she told everyone. However, the girls’ older stepbrother, Trace, says that it couldn’t have been Pete. Beth thinks that it would be awful if she’s leapt to the wrong conclusion and wrongly accused Pete of theft, but then again, she can’t be sure that Trace is right, either. Trace says that Pete was somewhere else at the time, but he doesn’t want to say where because, for some reason, that might also get Pete in trouble. Beth doesn’t know whether to believe him or not.

The kids are part of a blended family that has only been together for less than a year, so the children are still getting used to each other and their new stepparents. Beth likes their new little stepsister, Pip, but teenage Trace is harder to get used to. Trace is frequently angry, and much of his anger comes from his mother’s death. Beth knows sort of how Trace feels because her father died three years ago. She knows what it’s like to miss a parent, and try to keep their memory alive. Even though Beth doesn’t think of her stepfather, Champ, as being her father, she tries to be fair toward him and accept that he’s doing his best to take care of them. Sometimes, she wishes she could talk about it all with Trace, but Trace has made it clear that he doesn’t want to talk. Trace doesn’t like to talk about his mother and gets angry when anyone else even mentions her.

Beth thinks that Pete was the thief because the boy she saw running away was wearing a jacket like the one Pete has and has the same color hair. However, she didn’t actually see his face, and Maggie points out that other kids have similar jackets. Also, they found an old handkerchief of the house with the initial ‘Z’, and that wouldn’t belong to Pete. Beth has to admit that she may have been mistaken about who she saw. However, she can’t think of anybody whose name begins with ‘Z’, either. She worries that if she was wrong to say it was Pete that she saw she may have broken one of the Ten Commandments because she was bearing false witness. All that Beth can think of to make things right is apologize to Pete for being too quick to accuse him and try to find the thief herself, but she needs Maggie’s help to do that.

Why anybody would steal Christmas ornaments right off a tree is also a mystery. Some of the ornaments that belonged to Champ had some value and could possibly be sold for money, but most did not. The thing that Beth misses the most is the little angel that she had made for the top of the tree years ago. Its only value is sentimental, and Beth worries that a thief might just throw it away if he didn’t think it was worth anything. Also, if Trace is so sure that Pete is innocent, why can’t he explain where Pete really was when the theft occurred? Trace is sneaking around and seems to have secrets of his own. Then, after the family gets some new ornaments and decorates the tree again, the ornament thief strikes again! The new set of ornaments disappears, but strangely, the thief brings back Beth’s angel and puts it on top of the tree. If it had just been a poor kid, desperate for some Christmas decorations, they should have been satisfied with the first set. Is anybody so desperate for ornaments that they would take two sets, or is it just someone who doesn’t want this family to have any? And why did the thief return the angel?

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive (multiple copies).

My Reaction and Spoilers

The idea of somebody stealing Christmas ornaments sounds like a whimsical mystery for the holiday, but even though I’ve read books by this author before, I forgot that Wylly Folk St. John can bring in some of the darker sides of life. Much of this story centers around getting ready for Christmas, but there are some truly serious issues in the story. This is a book that would be better for older children. For someone looking for someone for younger children or a lighter mystery for Christmas, something from the Three Cousins Detective Club series would be better. (See my list of Christmas Books for other ideas.) It’s an interesting story, and I enjoyed the book, but I wouldn’t call the mood light.

The ways this new blended family learns to get along with each other and Trace learns to cope with his grief at the loss of his mother are major themes in the book. The parents try to be conscientious of the children’s feelings, making joint decisions and rules for the children as “The Establishment” of the house so none of the children feel like a stepparent is discriminating against them. The reason why the stepfather is called Champ is because he’s a chess champion, and Beth knows that her mother gave him that nickname so the girls wouldn’t feel awkward, wondering whether to call him by his name or refer to him as their dad. Beth is grateful for the nickname because, although she likes and appreciates Champ as a person, she does feel awkward about calling anybody else “dad” while she still remembers her deceased father. Trace calls his stepmother Aunt Mary for similar reasons, and Beth understands that. What she doesn’t understand is why Trace insists on wearing the old clothes that were the last ones his mother bought for him, even though they no longer fit him. Aunt Mary has bought him some nice new clothes that would fit him better, but he won’t wear them, and he even insists on washing his clothes himself, without her help. Beth asks her mother about that, but she says it doesn’t bother her because, if Trace is willing to help with the laundry, that’s less for her to do. Beth says that they ought to just donate all of Trace’s old clothes so someone else who can actually wear them can have them, but her mother doesn’t want to be too quick to do that because she doesn’t want to upset Trace. I can understand that because Trace is still growing, and it won’t be much longer before he won’t be able to wear those old clothes anymore anyway. The day that he can’t pull one of those old shirts over his head or put on old pants without splitting them will be the day he’ll be ready to get rid of them. Time moves on, and eventually, Trace won’t be able to help himself from moving on with it, and I think Aunt Mary understands that.

Part of the secret about Trace and his grief is that his mother isn’t actually dead, although he keeps telling people that she is. The truth is that his parents are divorced and his mother left the state and has gone to live in Oklahoma with her relatives. At first, Beth’s mother doesn’t even know that Trace has been telling the girls that his mother died, but when Beth tells her mother that’s what Trace said, her mother tells her the truth. She doesn’t want to explain the full circumstances behind why Champ divorced Phyllis and why she left, but she says that she can understand why Trace might find it easier to tell himself and others that she’s dead instead of accepting the truth. There is an implication that Phyllis did something that Beth’s mother describes as something Trace would see as “disgraceful” (I had guessed that probably meant that she had an extramarital affair, but that’s not it) that lead to the divorce. So, Trace is actually feeling torn between losing his mother and learning to live without her and his anger at her for what she did. He both loves and hates his mother, and that’s why he finds it easier to think of her as dead and gone and refuse to talk about her any further than deal with these painful, conflicting emotions. Beth’s mother also indicates that Phyllis was emotionally unstable, saying that the atmosphere in the household wasn’t healthy for Trace and his little sister because Phyllis “kept them all stirred up emotionally all the time”, and that’s why she didn’t get custody of the children and isn’t allowed to see them now. It turns out that there was a lot more to it than that, and that figures into the solution to the mystery.

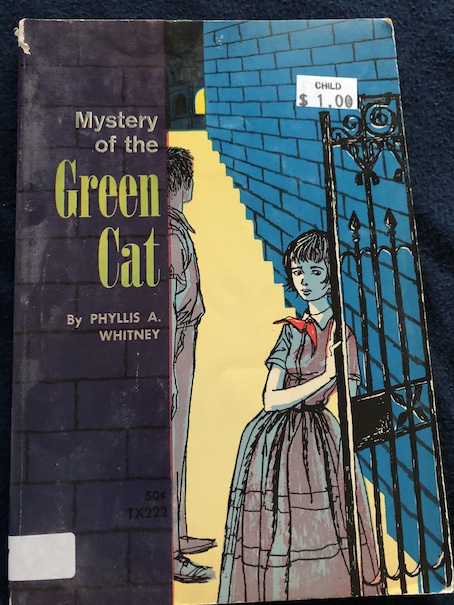

When I was reviewing an earlier book from the 1950s by a different author about children coping with grief and a new blended family, Mystery of the Green Cat, I talked about how books from the 1950s and earlier tended to focus on the deaths of parents when explaining why children lived in households with stepparents and step-siblings and how books from the 1960s and later started to focus more on the issue of divorce. This book kind of combines aspects of both of those types of stories. Beth understands the grief of a parent dying, and Trace has to come to terms with his parents’ divorce, which is a different kind of loss, although it’s still a loss. As I explained in my review of that earlier book, in some ways, divorce can be even more difficult for children to understand than death. Both are traumatic, but divorce involves not just loss but also abandonment (a parents who dies can’t help it that they’re no longer there, but it feels like a parent who is still living somehow could, that it’s their choice to leave their children and live apart from them, which leads to feelings of rejection) and the complicated reasons why people get divorced, including infidelity and emotional abuse. In this case, it also involves drug abuse.

I was partly right about the solution to the mystery. I guessed pretty quickly who the real thief was, but there’s something else I didn’t understand right away because I didn’t know until later in the book that Trace’s mother was still alive. Before the end of the book, Trace and Beth and everyone else has to confront the full reality of Phyllis’s problems. They get some surprising help from Pete, who has been keeping an eye on things and has more knowledge of the dark sides of life than the other children do. (Whether his father ever had a problem similar to Phyllis’s is unknown, but it seems that at least some of the people his father used to work with did, so it might be another explanation for Pete’s family’s situation.) Because Pete has seen people in a similar situation before and knows what to do. I had to agree with what Beth said that much of this trouble could have been avoided if Champ had been more direct with Trace before about his mother’s condition, but Beth’s mother says that sometimes children don’t believe things until they see them themselves. Champ was apparently trying to protect his children from Phyllis before, but because Trace had never seen his mother at her worst, he didn’t understand what was really happening with her. There is frightening part at the end where the children have to deal with a dangerous situation, but it all works out. Trace comes to accept the reality of his mother’s condition and that things will never be the same again, but he comes to appreciate the stepsisters who came to his rescue and brought help when he needed it.

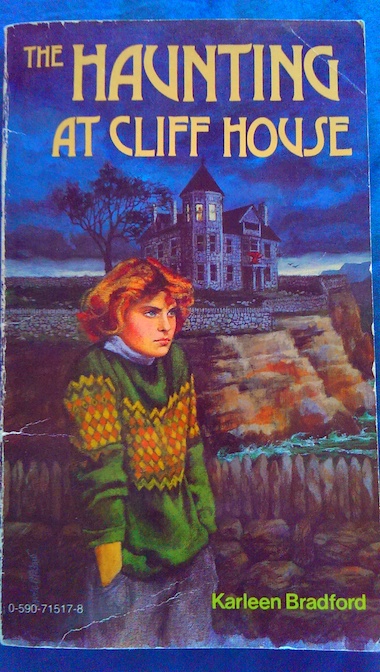

The Haunting at Cliff House by Karleen Bradford, 1985.

The Haunting at Cliff House by Karleen Bradford, 1985. The Headless Cupid by Zilpha Keatley Snyder, 1971.

The Headless Cupid by Zilpha Keatley Snyder, 1971. With their family suddenly much larger, David’s father bought a new house for them to live in. Actually, it’s a very old house just outside of a small town. People call it the Westerly house after the former owners. Not long after the family moves in, they find out that people used to say that the Westerly house was haunted. Mr. and Mrs. Westerly used to travel around the world with their two daughters because Mr. Westerly worked for the government, but after they settled down to a quieter life in this small town in the late 1800s, strange things started happening in their house. Rocks would fly around the house, seemingly thrown by invisible hands, and someone (or something) cut the head off the carved cupid on the fancy staircase banister. The head was never found. These incidents were reported in the local paper, and people believed that the Westerly family was haunted by a

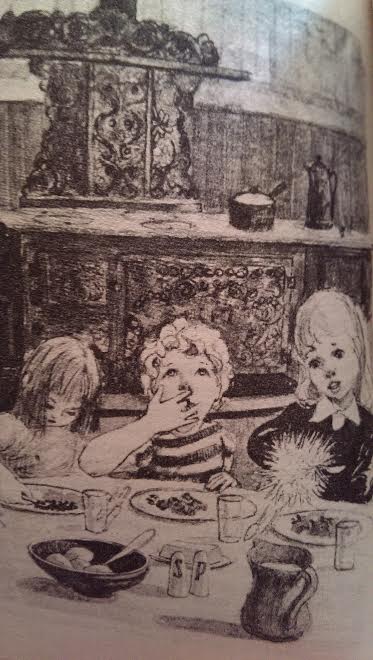

With their family suddenly much larger, David’s father bought a new house for them to live in. Actually, it’s a very old house just outside of a small town. People call it the Westerly house after the former owners. Not long after the family moves in, they find out that people used to say that the Westerly house was haunted. Mr. and Mrs. Westerly used to travel around the world with their two daughters because Mr. Westerly worked for the government, but after they settled down to a quieter life in this small town in the late 1800s, strange things started happening in their house. Rocks would fly around the house, seemingly thrown by invisible hands, and someone (or something) cut the head off the carved cupid on the fancy staircase banister. The head was never found. These incidents were reported in the local paper, and people believed that the Westerly family was haunted by a  Amanda is fascinated by stories of the poltergeist. A friend of hers where she used to live (one her mother didn’t approve of) was teaching her about the occult and how to do magic spells. When David tells Amanda that he thought that his mother was psychic, Amanda is surprised, and she offers to teach David and the other kids about magic over the summer. David eagerly accepts the offer because he finds the subject fascinating and because it’s the only thing that Amanda really seems interested in. The other kids are also fascinated at the idea, even the littlest ones, which takes Amanda by surprise. She had expected them to be scared.

Amanda is fascinated by stories of the poltergeist. A friend of hers where she used to live (one her mother didn’t approve of) was teaching her about the occult and how to do magic spells. When David tells Amanda that he thought that his mother was psychic, Amanda is surprised, and she offers to teach David and the other kids about magic over the summer. David eagerly accepts the offer because he finds the subject fascinating and because it’s the only thing that Amanda really seems interested in. The other kids are also fascinated at the idea, even the littlest ones, which takes Amanda by surprise. She had expected them to be scared. Just as with the Westerly family years ago, rocks are thrown around the house or found just laying around. Things are broken in the middle of the night. Have Amanda’s rituals somehow awoken the poltergeist once more? David has his doubts, suspecting that it’s part of Amanda’s playacting, but she is accounted for when some of these strange things happen. The younger kids are still more fascinated than frightened by these strange happenings, but their stepmother finds them particularly unnerving.

Just as with the Westerly family years ago, rocks are thrown around the house or found just laying around. Things are broken in the middle of the night. Have Amanda’s rituals somehow awoken the poltergeist once more? David has his doubts, suspecting that it’s part of Amanda’s playacting, but she is accounted for when some of these strange things happen. The younger kids are still more fascinated than frightened by these strange happenings, but their stepmother finds them particularly unnerving. There are some elements of the happenings, particularly the reappearance of the cupid’s head, that are never fully explained, although David ends up knowing more than Amanda by the end. Some aspects of the situation are hinted at. There may be a real supernatural event at the end of the story. Blair appears to have inherited psychic abilities from his mother, and there is a distinct possibility that the Westerly sisters who once lived in the house were just as unhappy with their parents for the changes in their lives as Amanda was with her mother. Although the “poltergeist” as it first appears doesn’t exist, it may be that the “poltergeist” of the past remembers what it was like to be young and unhappy and that she wanted to make amends for past wrongs and to help another troubled young girl to make peace with her life and family. But, if you don’t like that explanation, there is a more conventional, non-supernatural explanation that David considers, which equally possible. Personally, I think it’s a combination of the two, but it’s not completely clear. I think the author left it open-ended like that to make readers wonder and to preserve the air of mystery after the other mysteries have been cleared up.

There are some elements of the happenings, particularly the reappearance of the cupid’s head, that are never fully explained, although David ends up knowing more than Amanda by the end. Some aspects of the situation are hinted at. There may be a real supernatural event at the end of the story. Blair appears to have inherited psychic abilities from his mother, and there is a distinct possibility that the Westerly sisters who once lived in the house were just as unhappy with their parents for the changes in their lives as Amanda was with her mother. Although the “poltergeist” as it first appears doesn’t exist, it may be that the “poltergeist” of the past remembers what it was like to be young and unhappy and that she wanted to make amends for past wrongs and to help another troubled young girl to make peace with her life and family. But, if you don’t like that explanation, there is a more conventional, non-supernatural explanation that David considers, which equally possible. Personally, I think it’s a combination of the two, but it’s not completely clear. I think the author left it open-ended like that to make readers wonder and to preserve the air of mystery after the other mysteries have been cleared up. Sarah Morton’s Day: A Day in the Life of a Pilgrim Girl by Kate Waters, 1989.

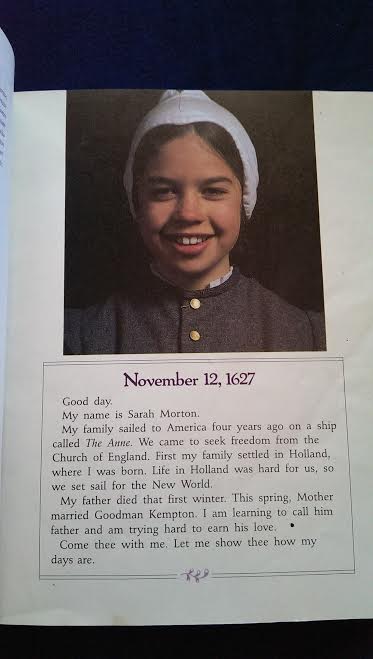

Sarah Morton’s Day: A Day in the Life of a Pilgrim Girl by Kate Waters, 1989. Although much of Sarah Morton’s day is taken up with chores, she also discusses her relationship with her mother and her new stepfather. The death of a parent was something that pilgrim children often experienced. After her father’s death, Sarah’s mother remarried, and Sarah is concerned about whether her new father likes her.

Although much of Sarah Morton’s day is taken up with chores, she also discusses her relationship with her mother and her new stepfather. The death of a parent was something that pilgrim children often experienced. After her father’s death, Sarah’s mother remarried, and Sarah is concerned about whether her new father likes her.