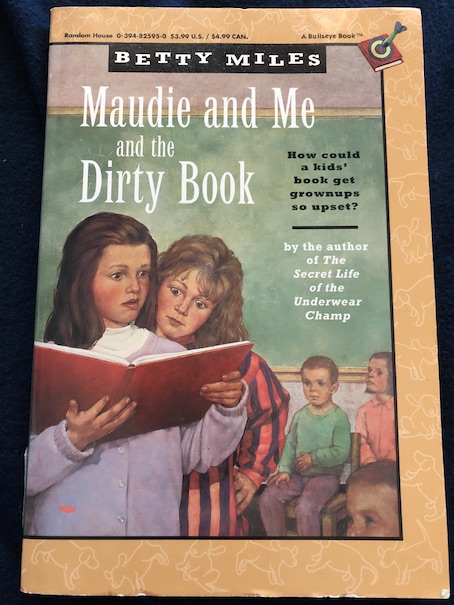

Maudie and Me and the Dirty Book by Betty Miles, 1980.

There’s a lot to discuss here, so I’m going to break up this whole entire review into themed sections and because this is going to be pretty long, I’m giving the link to the copies of the book on Internet Archive here.

Introducing Kate

Kate thinks of herself as a perfectly ordinary middle school girl. She’s certainly trying her hardest to be normal and cool and hang out with the “right” people. (In that compulsive way some people have when they’re just really trying way too hard because they feel like they’re supposed to. I’ll be honest, I found Kate to be a very trying character for about the first half of the book, and I have things to say about that in my reaction.) She’s very deliberately “normal” and her biggest worry is figuring out who the “right” people are to be friends with that it takes her completely by surprise that volunteering to take part in an English class project lands her right in the middle of a community scandal.

It’s Kate’s first year of middle school, and so far, Kate likes English class and her teacher, Ms. Plotkin. English was always her favorite subject, and Ms. Plotkin is one of those people who can make any subject or project sound exciting. Ms. Plotkin has a friend who is a first grade teacher at a local elementary school called Concord, and the two teachers think it would be a good interschool project to have middle school kids volunteer to read to the younger students to get them excited about reading and books. Kate volunteers right away because she loves reading and little kids. She’s been thinking that she’d like to earn some money by babysitting, so this reading project would be good experience that she might be able to use to get babysitting jobs.

Kate hopes that her best friends from elementary school, Jackie and Rosemary, will also volunteer for the project so they can do it together, but they don’t. The only other kid in class who volunteers is Maudie. Maudie has already been unofficially labeled as one of the uncool kids that all the cool kids avoid because they’re just not like the other, cool kids. There’s nothing seriously wrong with Maudie, but she’s a bit fat and Kate thinks of her as a kind of “dope” because she isn’t trying to act cool or normal like Kate and her friends do and generally isn’t trying to be like them. Kate even actively participates in all of the jokes and mean comments about Maudie that the other kids make behind her back because these shared “jokes” and slurs about Maudie are part of their bonding process with each other and define their in-group as being not-Maudie type people. (Oh, yes, I definitely have issues with Kate that I will rant about later.) That’s why Kate is horrified at first that she might have to actually work with and talk to Maudie if they’re the only ones doing this project together. Maudie is kind of fat, doesn’t quite dress like the other kids in small ways, and just kind of gives off an uncool vibe that’s sure to get Kate labeled as “uncool” if she has to hang out with her for this project. If that happens, she might become (gasp!) a not-popular person because the “right” people will avoid her. (Oh, noes! However will you manage?)

Being Nasty and Condescending to Maudie

Maudie tells Kate that she volunteered for the project partly because she really likes working with kids, like Kate does, and she was hoping that she and Kate might be friends since they like the same sort of things. Maudie comments that she doesn’t like the atmosphere of this middle school because of people’s attitudes and obsessions with hanging out with the “right” people and being part of cliques. These are mature, sincere comments that shows insight into someone else’s character, and Maudie is correct that Kate is part of an exclusionary clique with Jackie and Rosemary. Maudie’s comments are actually a rather unsubtle hint at Kate that she’s being a bit of a snob and that she could be a nicer person if she could think outside of her snobby clique. Maudie is fully aware of what Kate and her friends are saying about her, and this is an invitation to Kate to change and be a friend, but Kate doesn’t get it at first. She’s too worried about seeming too friendly with uncool Maudie and what other kids will think of it, particularly Jackie and Rosemary.

Kate even thinks that she feels sorry for Maudie, wondering what it’s like to be her and mistaking her sincere offer of friendship for a desperate need to make a friend. Maudie’s actually just being a normal level of friendly in this conversation, but Kate’s assumptions about uncool people have given her a false view of reality. When Kate tries to imagine what it’s like to be Maudie, she’s not actually imagining herself as the real Maudie because she doesn’t really know Maudie at all and wasn’t really listening to Maudie when she was talking because she spent that time thinking about how not to say too much to her or be too friendly. Even though Kate kind of acknowledges that there’s nothing really wrong with Maudie, she still thinks of Maudie as a problem because of the social implications of seeming to like a person the “right” people don’t like, not realizing that the meanness she’s helping to enable is the real problem. (There’s nothing really wrong with Maudie, and I see a lot wrong with Kate and her friends because of their attitudes and the way they think about things. I’d also like to point out that Kate is not filled with sympathy at this point; she’s been nothing but self-pitying because of what she thinks is going to happen to her popularity at school for being seen with the wrong person. She’s projecting that self-pity onto Maudie who is, by herself, just expressing honest sincerity.)

At first, Kate tries to think if there’s a way that she can back out of the project, but in the first glint of honesty about her, she admits that she actually wants to do the project for the sake of the project itself. I always like people who have a particular hobby, cause, or interest that they like for its own sake because that’s a sign of a real personality or character. Standing up for a special interest and doing it anyway, even if nobody else is, also shows a strength of that character that’s worthy of respect. This is the one trait that made me willing to stick out the book with Kate, even though I seriously didn’t like her, because it showed the promise of character development.

Kate also finds additional willingness to continue with the project when Jackie passes her a note telling her to get out of the project so she won’t be “stuck with fat Maudie.” Even though Kate realizes that she was thinking the exact same thing and might have even said so out loud among her friends, it actually looks really bad and mean written out on paper in black-and-white. Kate thinks that writing it down makes it worse, not realizing that there’s really no difference at all, and it’s the thinking behind it that needs to change. Also, she finds it irritating that Jackie seems to think that she can tell her what to do. (I think that’s a legitimate complaint.) After they get out of class, Jackie even snubs Kate to hang out with other kids, and Kate knows that she’s lying to her about the reasons why.

Kate’s mother is actually glad when she hears that Kate will be doing the project with Maudie. Kate’s mother says that she doesn’t like it that Kate is so clingy with her old elementary school friends and that she’d like to see her branch out and meet some new people. (She doesn’t say why she wants Kate to do that, but at this point in the story, I’d already figured out why.)

When it’s time for Kate and Maudie to go to their volunteer project, a girl in class whispers a mean joke about Maudie to Kate, and Kate giggles. Then, Kate sees Jackie whisper something to the other girl and the two of them giggle. Kate suddenly wonders if Jackie is making mean jokes about her, and suddenly, it doesn’t seem as funny anymore.

(Oh, good grief! Is this the first time in her life she ever thought of this? You know, people who gossip and make fun of others (surprise!) spend their time gossiping and making fun of others. It’s what they do, and yes, they do it to different people, depending on who they’re talking to at the moment and who isn’t around to know. If someone gossips meanly about someone else to you, then yes, you can be confident that they’re gossiping meanly about you and making fun of you with someone else when they think you’re not listening. It’s their mode of communication and how they bond with people, and they have no idea why you’d have a problem with them doing to you that because you laughed with them before about someone else, so you must be okay with it and have no reason to get mad. I get impatient with people who don’t think about these things, and if Kate had the imagination to really put herself in someone else real shoes before, she should have thought of this long ago. She should know the kind of person Jackie is from years of experience with her, and she should have figured out that she wouldn’t like other people to say things about her that she’s been saying about Maudie. I feel like Anne Shirley from Anne of Green Gables, saying that if she had any real imagination, Kate could have put herself in someone else’s place and figured out what other people might be feeling, but she doesn’t do that because she’s too self-absorbed and doesn’t get it until someone does it directly to her within her hearing. Kate has plenty of self-pity but no sympathy, at least not at this point.)

The first chapters of this book were pretty painful for me because I had to put up with the kind of people I really hate, including the one telling the story, but fortunately, it does get more interesting from this point on. As they walk over to the elementary school, Kate and Maudie have a fun moment where they throw snowballs at a stop sign, and Kate forgets to be “cool” and snobby. At the elementary school, Kate has fun meeting the cute little first graders, and the first grade teacher reads Make Way for Ducklings to the class. Maudie also introduces Kate to the elementary school librarian because this is Maudie’s old elementary school, and she knows the faculty. The girls talk about Maudie’s time at Concord, and Maudie admits that she kind of misses it because it just seemed so much more friendly than Revere Middle School. Kate feels a little sorry for Maudie because she mentions that her best friend has moved away, and she asks if she’d like to go to the library together to pick out some books. Maudie accepts and says that she can hang out at her house afterward, if she wants, and Kate gets worried again that Maudie is starting to think that they’re actually friends or something. (Once again, oh, noes. However will you manage, Kate? You might accidentally give off vibes that you might be a likeable person or something, and how ever will you be popular if too many people in that vast sea of “wrong” people outside of your tiny clique like you?)

Kate and her friend Rosemary talk about the project a little, and Rosemary asks her what it’s like working with Maudie. Kate says that Maudie isn’t bad when you get to know her, and she is pretty good with the younger kids. Rosemary says that she’s been thinking that the comments people keep making about Maudie are really mean and she doesn’t deserve them because there’s nothing really wrong with her. Kate agrees.

Kate feels a bit bad about going to the library with Maudie because Jackie and the others are going skating, and Jackie is acting like she doesn’t even care that she isn’t going to be there. (It occurred to me that Jackie might actually care that Kate’s doing something with someone else and is trying to play it cool, but it’s dumb because that attitude just drives people away anyway. Either that, or she’s realized that Kate is somebody else to make fun of or gossip about with other girls, and that’s easier to do when she’s not there to defend herself.) Kate not only feels a little bad that she’s missing out on something with her friends, but she comes to realize that she’d rather go to Maudie’s house after the library after all because Maudie at least acts like she wants her around and Jackie doesn’t. Jackie seems to dodging her and trying to get rid of her to hang out with others. Also, it seems like all the other girls are obsessed with the new boy at school, Steve. Kate knows Steve slightly because his parents bought their house through her parents, who are realtors. (Ah, perhaps that’s why Jackie is acting weird! Instead of seeing Kate as her old friend, she’s starting to suspect her of being a rival for a cool guy at school.) However, Kate doesn’t really know Steve very well, and she finds the other girls’ fawning attitudes toward him embarrassing.

At the library, Kate and Maudie talk about their favorite kids’ books and try to pick out some books that will really please the first graders. Kate remembers that one of the first graders had told her that he was excited about getting a puppy, so she decides that she’d like to get a book about puppies. The librarian, who is actually a distant cousin of Kate’s, suggests a book called The Birthday Dog. It’s about a boy who wants a puppy for his birthday. The dog who lives next door is going to have puppies, but the puppies won’t be born in time for his birthday, and he’s disappointed at not getting a puppy for his birthday. Then, he gets a birthday card that says that he can have one of the dog’s puppies after they’re born. The boy and his father even get to see the first puppy being born and how the puppy grows until he’s big enough to leave his mother. The librarian says it’s a good book because the pictures are clear and realistic. The girls decide that they’ll use this book because of the puppy theme and because the boy in the story is about the same age as the first graders. This is where the censorship issue comes into the story. (More on this below, much more.)

Note: The Birthday Dog is not a real book, at least not as far as I can tell. Some of the children’s books mentioned in this book are real books, but some of them aren’t. I think it’s better for the purposes of the story if this picture book is not real because real books often have emotional baggage attached to them, possibly because of feelings of fond nostalgia because people liked them when they were young, resentment because of something the books said or the manner in which teachers or parents forced the books on them, or things people have heard other people say about books, even if the listeners haven’t actually seen the books themselves. For the purposes of this story, which is about examining people’s reactions to controversy, it’s better to approach this particular book with a clean slate, seeing it for what it’s described as being in the story and people’s reactions to it for what they are, removed from any personal emotional baggage. Assume from this point on that the book is exactly as the characters who read it describe it as being, nothing more and nothing less and that all reactions to the situation are exactly as described, nothing more and nothing less.

Kate does go to Maudie’s house, and she starts to learn that she and Maudie have some things in common and that even their mothers act very much the same way. Maudie’s mother has also been pressing her to make some new friends. Kate discovers that Maudie also enjoys old Marx Brothers movies and Maudie has a talent for impersonation. (Finally! A thing that you like, Kate! Early in the story, she was mainly about what she didn’t like and her preoccupation with being liked by the right people. Cool people in stories (and frequently in real life) never seem to genuinely, unironically like anything, especially things that are honest, goofy fun. It’s especially heartening to me that she likes something that not all of her friends like, so Kate is actually showing more signs of independent thoughts and feelings and interests beyond generic coolness and popularity-building. I’m emphasizing this because this was the point in the story to me that Kate started seeming like she might be a real person with an actual personality. Up to this point, she seemed like a two-dimensional wanna-be popular mean kid snob with no self-awareness.) By the end of the day, Kate actually begins looking at Maudie like a real friend and doesn’t seem to mind the idea. (Which means that Kate will finally stop getting on my nerves with her snobby, unaware mean girl act, and I can stop belaboring that point.)

A Delicate Discussion and an Indelicate Response

Note: This is the part of the story where we get into issues of censorship and controversy in children’s literature. I think the earlier social machinations, cliques, and using negativity and putting other people down for the sake of personal promotion also ties in with this theme, which is why I went into detail about that before getting into this part of the book, but I’m going to discuss why it’s important later. One thing to keep in mind is that it isn’t unpopular Maudie who selects and reads the controversial book; it’s Kate, the one who’s been trying desperately hard to fit in with the “right” people and be popular and “normal.” Kate is about to be the one who will be ferociously judged by both other kids and adults for doing something controversial. For now, let’s get into the book controversy.

The next time the girls go to the elementary school, they show their books to Ms. Plotkin before they leave, and she approves of their choices. (This is key for the censorship issue. Keep in mind that the girls didn’t choose their books by themselves. They had recommendations from a librarian and the approval of their teacher for their specific selections.) Maudie reads her book, Little Bear, to the class first, and then Kate reads The Birthday Dog. The part where the puppy is born describes the mother dog’s stomach rippling, how she pushed the puppy out, and how she bit at the thin sac that covered the puppy when it was first born. Kate is reassured that the kids seem to like the story, but then the first grade teacher allows the students to ask Kate questions about the book, and Kate isn’t prepared for what the kids ask.

When one of kids ask how the puppy got inside its mommy, Kate looks at Ms. Dwyer, the first grade teacher, and Ms. Dwyer just nods at Kate to answer, not giving her any help or advice about what to say to a first grader about this.

(I just have to step in again at this point and say, if it were me as the adult present for this scene, I’d have noticed Kate’s discomfort, recognized this as a sensitive topic, and stepped in and said, “I’ll take this one, Kate,” and then said something that answers the question in the simplest, most literal terms without getting too deep or detailed. In this case, I might have said something about how that’s simply the way that babies begin to grow. It’s normal for babies to grow inside their mothers before their born because they are very small and weak at first and need some time for their bodies to develop before they can do even simple things like move around, eat, and breathe air on their own. Some animals lay eggs, like chickens, and the babies grow inside them and hatch out of them when they’re ready, and some animals have the babies grow inside their own bodies, like dogs, until they’re ready to come out. The mother’s body helps to protect them and give them what they need so they can grow. People are like that, too, and that’s why pregnant women look big around the middle before their babies are born, because the baby is growing inside them. But, it’s not a good idea to make a big deal about the way people look because you don’t want to make them feel bad or too self-conscious about their appearance (and I hope you know that I mean you too, Kate). Just be extra nice to pregnant people because it’s hard work carrying a growing baby around. If you want extra details, I recommend that you ask your parents because they’ve had kids before, and I haven’t, so they could describe how that feels better than I could.)

Kate stumbles about a bit, searching for a way of describing it, saying something about the father dog, but stopping because she isn’t sure what she should say or if she’s saying too much. But, some of the first graders begin blurting out bits and pieces of what they know, and some of them know more than Kate expected. One of the kids says that the father dog puts a seed into the mom. Kate says that’s correct and that’s called “mating.” Soon, little first graders are using words like “vagina” and “penis.” It’s important that the first graders are the ones who introduce these words into the conversation themselves, not Kate or the teacher or the book. Little kids like to receive recognition for things they know or things they have, so some of the kids are more than happy to show off what they know and to publicly declare which of those two they have. The first grade teacher just says that what they’re saying about the mother and father dog mating are correct and that’s how puppies start. Kate has a moment of panic when she’s afraid that the kids will start thinking about human babies and how she doesn’t want to go into detail on this subject, and she’s relieved when the kids return to the subject of dogs and start talking about their pet dogs’ names. Again, kids like to receive recognition for things they have and to compare things they have with others. When it’s pet dogs, it’s not as embarrassing.

When it’s time for Kate and Maudie to leave, Ms. Dwyer says that Kate handled the situation well, saying, “Kids this age can be embarrassingly frank! But I don’t want them to think there’s anything wrong with their natural curiosity. I’m glad you could answer them so matter-of-factly.” The girls bond over this odd, embarrassing incident, and they think that Kate seems to have handled it okay. Kate even reads the book to her elderly Aunt Lucy at her nursing home and some of the other elderly people there, and they like it, too. Then, the girls and their teacher start getting parental complaints.

The complaining parents in the story don’t handle the situation with grace and understanding, and they make things worse. Rather than defusing the situation and diverting focus from an issue that they didn’t want to discuss in the first place, they blow it up to the point where nobody in the community can ignore it. They phone the principal of the elementary school and the principal of the middle school. They go down to the library and demand to see copies of The Birthday Dog. Soon, everybody in the area hears some version of what happened in the first grade classroom, and just like in a game of Telephone, the events become mangled and confused. This is what I mean about misconception and misrepresentation and how people use these to further an agenda. Be prepared for more of this.

When the girls return to school after the weekend, Ms. Plotkin tells the girls that they need to have a talk with their principal. In the principal’s office, they tell the girls that some parents have complained about The Birthday Dog and the discussion that took place afterward. Ms. Plotkin and Ms. Dwyer take responsibility for allowing Kate to read the book and discuss it with the younger kids, and Ms. Dwyer says that she thinks Kate handled the discussion well. The girls feel like this situation is unfair. They didn’t really do anything wrong, and there are other people involved who also didn’t really do anything wrong. They don’t want the principal to blame their teacher for what happened. Kate feels responsible for having chosen the book in the first place, and Maudie even defends her, saying it was a good book and Kate didn’t do or say anything wrong. Kate appreciates her support because nobody had a problem with the book that Maudie read, and she didn’t have to stick up for her. The librarian helped Kate to choose it. Kate picked it based on her recommendation, so she’s involved, too.

The principal tells Kate that he wants to see the book in question, and he asks Kate to recount the entire discussion in the first grade class. It’s an uncomfortable conversation because Kate is a young girl and the principal is a grown man who is not related to her in any way, and Kate doesn’t like the idea of being forced to discuss anything related to sex with him, even if it’s an innocent recounting of a mildly embarrassing conversation. (If some parents don’t like being put on the spot discussing the issue with their own children, just have a little imagination and understand that this is even more uncomfortable for Kate, who is not related to the principal or anyone else involved with the exception of the librarian, and she is also subject to their authority because she’s a student and a minor. This is what their reactionary complaints have led to, and there’s worse to come.) Kate is accurate in her description, and the principal warns Ms. Plotkin about the importance of choosing appropriate materials for students because of parental anxiety about sensitive issues. Even though the principal acknowledges that the book seems pretty innocent from their description, the anxious, complaining parents can cause a lot of trouble for the schools, so they’re going to suspend the interschool reading program for the present.

Misconception, Misrepresentation, and the Fallout

This is where Kate begins to experience the varying reactions that people have to the incident, and the ways in which people approach the situation and Kate herself say things about their characters and their relationship with Kate. Kate begins to discover who her real friends are and has to face the wrath of people who are more concerned with their own agendas than they are with her or even the little first graders.

Of course, word spreads around the middle school that Kate and Maudie were called to the principal’s office, and rumors spread about the reasons why. Some of the students have heard bits and pieces of the story, and they’ve become exaggerated, just like the mean girl comments that people were making about Maudie in the beginning. Josh, Kate’s older brother, seeks her out at lunch and demands to know what people are talking about when they say that she was reading a dirty book to first graders and got called to the principal’s office about it.

Kate defends herself, saying that the book wasn’t dirty. She hates it that people are calling the book dirty because they’re making her seem like she’s a dirty person for reading it. Kate is afraid that people are looking at her like she’s a monster, even though she didn’t do anything wrong, and that they’re all going to hate and avoid her now because people are saying things about her behind her back and everyone will think that there’s something wrong with her when there isn’t. (Oh, gee, why does that sound familiar? This is where the story about censorship starts to tie back into the social maneuvering and nasty gossip from before. Kate started out being one of the active participants in this type of behavior, along with what she considered the “right” people, and now, she’s seeing what it’s like being on the receiving end of that same behavior from the same “right” people.) After hearing Kate’s description of what happened, Josh advises Kate not to panic and not to let anybody get to her or to try to explain the situation to anyone because it’s nobody else’s business. Their parents will support Kate and defend her to the complaining parents.

Rosemary also gives Kate a kind response, asking if she’s okay and telling her that not to feel bad if people are trying to make her feel bad for no reason. Kate does confide in her about the situation, and Kate, Rosemary, and Maudie also share a laugh at the ridiculousness of the situation because it was kind of funny to see the little first graders saying all of that stuff, completely unaware that it was potentially embarrassing, and even the principal looked embarrassed when Kate honestly recounted what the first graders said. Rosemary invites Maudie to join her and Kate in having lunch with Jackie and Christine. Jackie pesters Kate for details about what happened, but Kate decides that she doesn’t want to discuss it with them, and Jackie acts jealous when Steve says hi to Kate. Jackie and Christine leave the other three girls, confirming that an imagined rivalry over Steve is part of the reason why they’re acting like jerks.

Kate even thinks, “I didn’t know why Maudie would want to sit with us, if Jackie and Chris were going to act so snotty. I suddenly wondered why I should always sit at the same table. At least every time. I realized that no one was making me. I could sit anywhere I wanted. Maudie and Rosemary would probably go with me.” This is exactly what I was thinking and glad that Kate had this realization. Rosemary is a real friend who is worth retaining, but Jackie is drifting away, and it’s just as well for the other girls to let her go and develop a budding friendship with Maudie.

Kate’s parents are supportive of her, but they also worry that a fight over censorship could tear their community apart. Kate’s mom said that the elementary school principal would be required to take any complaint by parents seriously, but Kate points out that, by choosing to take this complaint seriously to spare the feelings of the adults seems to legitimize the complaint, like a tacit acknowledgement that something inappropriate happened even when it didn’t and that Kate did something wrong, even when she didn’t. In trying to spare the feelings of the uninformed and panicky parents, Kate feels like the adults seem prepared to throw her under the bus and slander her all over town. The middle school principal’s obvious lack of support for Ms. Plotkin also seems to be throwing her under the bus. It’s also already too late to worry about a fight starting, because it’s already begun and battle lines are being drawn.

I’d also like to point out that, to an extent, the battle lines were already drawn before Kate ever joined the reading program and read the book. The way that people react to issues stems from the issues in their own lives, their emotional baggage (you can’t live to adulthood without having at least some because real life experiences do that), and the goals that people want to accomplish. Kate was just unaware that these adults cliques and issue-based factions already existed, which is why she didn’t see this situation coming and accidentally put herself into the middle of it as their latest, hot-button target issue. It seriously bothered me because some of the adults in the story are bonding with their respective factions over the negative things they’re saying about young Kate, not unlike how Kate and her friends were originally bonding over saying nasty and derogatory things about Maudie.

The Millers, a difficult family who have been routinely complaining to Kate’s parents about a house they bought from them, frequently demanding that they solve problems that the Millers caused themselves, phone yet again to complain to them about Kate because the child of a neighbor of theirs was in the class where Kate read the book. (Note: It was not their child in the class, it was a neighbor’s, and we are not told how the neighbor feels about it. The neighbor likely does not know that Mr. Miller is even making this telephone call.) Mr. Miller thinks that Kate’s dad owes him an explanation for something he didn’t witness and no member of his family was involved in and that he just kind of vaguely heard about. This issue has nothing to do with the Millers and is none of their business, but from the descriptions of their behavior, the Millers have personal issues and a desire to make others accountable for things while not being accountable for things they do themselves. This is part of how people’s personal issues dictate where they stand on public ones and how they demonstrate what they’re thinking and feeling. It wouldn’t matter to the Millers what Kate said or did because they’re just the type to want to stick something to someone, anyone, for any reason they can find. It doesn’t have to make sense because the Millers are unreasonable people, so they do unreasonable things. That’s what makes them unreasonable people. Maybe it does make a kind of sense when you think about it.

Right after that, a parent of one of the students in Ms. Dwyer’s class calls to express her support for Kate and offer her a babysitting job, like Kate originally she wanted. In every conflict, there are going to be supporters as well as haters, and it’s not all bad to be part of a controversy when you’ve got the right supporters. The same choice or set of circumstances will get different reactions from different people, and Kate is learning that there’s no such thing as being popular with everyone. No matter what she does in her life, she will draw some people to her who understand and accept her while others will be pushed away, and it’s just a question of who she wants to bond with and how. In this parent who understands the situation and approves of how Kate has been handling it, Kate has finally found a “right” person to be friendly with who is using helpfulness and positivity instead of meanness and negativity and someone to bond with over shared values.

Ms. Plotkin comes to Kate’s house after a meeting of the teachers and principals involved and the librarian, and she says that they’ve come up with some ideas for defusing community complaints. However, word of the controversy has already spread, and Kate’s entire family is feeling the impact. People are writing angry letters to the editor of the local paper, and one of those people happens to be the father of Josh’s girlfriend, Denise, prompting her to break up with Josh. Kate reads these letters and feels horrible. They imply that she’s immoral or that she’s a dope. Kate thinks, “I wished I could just laugh at them, but I couldn’t. Those dumb letters hurt my feelings. Whoever made up the poem about ‘sticks and stones’ was wrong. Words do hurt you.” I’m glad that she realizes that, but I still would have liked it better if she hadn’t been a snob at the beginning of the book and said the things she said about Maudie before she got to know her. Kate has improved as a character, but I have less sympathy for someone when they’re on the receiving end of something that they carelessly dished out to others.

Denise’s father’s letter actually isn’t too bad, but Kate feels bad that he points out that it’s not right for someone who doesn’t know a child personally to bring up the topic of reproduction before a child is ready to hear about it, and “it is impossible for even the most well-meaning teacher to know when the moment is right for every child in class.” Kate doesn’t want to think that she accidentally pushed a little kid into learning something difficult before they were really ready and shocked them. Still, Kate remembers that Denise’s father wasn’t there and didn’t see the book or hear the discussion and might not understand what really happened. Kate finds out that Denise actually isn’t upset with her family; she’s upset with her parents for being closed-minded and making a fuss. She didn’t break up with Josh because she’s upset with him or with Kate or the rest of their family. It was because she’s worried about what they all might be thinking of her because of her father’s public reaction and criticism of them. She’s embarrassed by the way her father wrote that letter and added to the controversy, although Kate appreciates it for being one of the more thoughtful and less hateful letters.

(It occurs to me at this point that Denise’s father himself might be one of those “well-meaning” adults who maybe don’t know “when the moment is right” to say something because they don’t fully understand the situation or how his decision to say something affects other people. After all, he has directly affected his own daughter, the kid he should know the best, because he hasn’t considered her feelings or her position or talked her about the situation before he made his public reaction. Maybe just being someone’s parent alone isn’t enough to fully understand the child or the child’s life without that necessary communication.)

Steve tells Kate that some parent told his mother that “young children had been exposed to explicit sex materials” and was up in arms about the general reading materials in schools. This woman and some other parents had a private meeting about campaigning for “decent books.” Steve’s mom wasn’t impressed by that because she’d read some of her kids’ books from school and thought they were fine. The woman, Mrs. Bergen, accused Steve and his sister of reading smut behind their mother’s back and said that their mother should make them show her the books they didn’t show her before. Steve says that, when he used to live in California, there was a big controversy because an eighth grade teacher wanted kids to read Anne Frank’s diary, and the parents said all of the same things about that. (In the unabridged diary, there are parts where Anne Frank reflects on the concept of sex, getting her period, and her body parts, which she looked at on herself using a mirror. If a kid makes it to eighth grade (about 13 or 14 years old) without knowing what these things are or being afraid of them, they’ve got bigger problems than their reading material. That’s my opinion. Kids normally talk among themselves about these things, and for a person not to know any this stuff, they would have to be restricted from forming close friendships with other teenagers, denied the opportunities to discuss it honestly with family, and in modern times, restricted internet access where various sexual references abound and information is a mere Google search away. None of that would be healthy for a person who is only 4 or 5 years away from legal adulthood in our society.)

Kate is actually glad that Steve understands the issue and has opinions about it. She thinks that she wouldn’t like a boy who had no opinions. That was actually a major part of my original complaint about Kate. In the beginning, she didn’t seem to have any kind of individual personality or opinions of her own beyond her desire to fit in with the popular mean kids. By this point in the story, I felt that Kate was becoming a much deeper, more thoughtful character than the shallow, thoughtless little snob she seemed to be at first, so I was happy to see her coming to this realization and to agree with her about something.

Conflict Resolution and the Issue of Control

Kate’s feelings finally overwhelm her in English class, after she’s been confronted by many people about the “dirty” book. Mrs. Bergen, a character who has not actually appeared anywhere in the story until this point, has been busily calling other parents and generally stirring things up with an exaggerated story that bears little resemblance to the real incident. Mrs. Bergen is clearly a woman with her own agenda and is taking advantage of the situation to manipulate others into doing what she wants. Kate goes on a rant in class about how unfair the situation is and how she doesn’t want everyone to look at her like she’s a monster or a sex maniac.

The class has a real discussion about the issues of censorship and freedom of speech and what teachers have to consider when they’re choosing “appropriate” material for the kids in their classes. Ms. Plotkin says that there are even some books that she’d rather her students not read until they’re older and have more life experience. (I have a story about that from when I was ten, when a friend “borrowed” a romance novel of her mother’s and told me the most shocking bits, much of which I didn’t really understand at the time. Oddly, that’s not what I ultimately took away from that incident, but since we’re on the topic, I will tell you what I took away from that below.) One boy in class talks about how his parents say that there are things that kids should only learn from their parents, and another boy says what if parents don’t tell the their kids things they really need to know because kids have to learn it somewhere. Jackie comments that she thinks some parents are just too embarrassed about things themselves and so they don’t want their kids to know about them, not because the kids can’t handle it but because the parents can’t. (I thought this was actually a surprisingly perceptive comment from her. Actually, I don’t think that Jackie isn’t perceptive. I just think that she doesn’t always use her social perceptions for good.) Mrs. Plotkin says that’s part of it, but also parents are genuinely concerned for their kids. They worry about a lot of terrible things that kids get exposed to through TV and life in general, and most of it is beyond their control, so they focus on the parts that they can control, like the kids’ reading material.

The kids in the English class say that this whole situation is unfair because none of the complainers were there during the original reading and discussion. Not all of these people even had kids who were involved, most of the complainers haven’t even seen the book in question, and a number of them have only gotten upset because they talked to someone like Mrs. Bergen, who wasn’t there and stirred them up with her exaggerated story. They’re reacting in some over-the-top ways when they don’t really know the real situation and don’t even stop to consider that they don’t know the real situation. Their reaction is having a negative effect on innocent people’s lives, by needlessly damaging innocent reputations, and that’s irresponsible. How people approach a situation and try to control their lives impacts others. While we’re discussing the issue of control, it’s also questionable how much some of these adults are controlling themselves, which is the one thing that everybody truly can control in life, even if they have no control over anything else. While these adults are yelling at people at the supermarket and writing angry letters to the editor, there’s something else that they’re not doing that’s even more important and would be much more responsible: sitting down with their kids to have an honest talk about life and their feelings and getting real feedback from their kids about it all to see how they’re really affected.

Mrs. Bergen finally makes an appearance when she confronts Kate’s mother at the supermarket, trying to get her to join her new group, Parents United for Decency. Kate’s mother tells her off before revealing that her daughter is the one who read the book at the school. Mrs. Bergen and her followers are shocked, and some of the mothers seem suddenly uncomfortable to have to deal with the people they’ve been maligning face-to-face, in a setting where they seem perfectly normal and can see that there is nothing really wrong with them. Mrs. Bergen calls Kate’s mother prejudiced because it’s her daughter who read the book, and Kate’s mother tells her that she’s the prejudiced one. She says that the librarian who recommended the book is her cousin and graduated at the top of her class, and she trusts her professional opinion of the book over their “misinformed ranting” when they haven’t even read it.

The local paper also prints some sympathetic letters about Kate and the book, including one written by her great aunt in the nursing home, saying that Kate read the book to her and her friends, and none of the senior citizens were shocked by it.

The issue ends up being discussed at a special public meeting of the school board, where the board votes about whether or not to allow the interschool reading project to continue. Kate feels awkward when her family sits with Denise’s family at the meeting, after the letter that Denise’s father wrote. However, Josh and Denise have made up, and their fathers are actually old friends who worked together, so the families don’t want to sacrifice that relationship for just this one issue. Personally, I agree with Kate’s awkwardness and feel like, if they were real friends, the two fathers could have just talked to each other privately and directly about what happened before Denise’s father sent one of the public letters that stirred the pot. Not only didn’t Denise’s father talk to his daughter, he didn’t even talk to his old friend about the issue before writing an impersonal public letter, read by the whole community! I don’t know why people don’t think of these things. Kate thinks that people around them at the meeting are looking oddly pleasant and civilized, considering how angry and ranting they were in the letters they wrote and realizes that you can’t always tell who’s a mean person because people don’t always look mean when they act it. “It would be more convenient if mean people looked mean so you could tell.”

When the middle school principal gets up to speak, he describes the reading project in a way that makes it sound dull but harmless. When Mrs. Bergen gets up to speak, she spins a story about how the whole thing was a dastardly, premeditated plot on the part of the teachers, who were scheming to tell impressionable children about sex and undermine their morals. (This book was published in 1980, 40 years ago and two years before I was born, so here, I paused for a moment to consider what Mrs. Bergen would have thought about things that “impressionable” children routinely type into Google, completely unprompted. When inquiring minds want to know something, they seek out sources of information, and kids today know way more about some of that stuff than I had the opportunity to learn, not counting that incident when I was ten. Actually, kids write things on the internet that aren’t exactly clean, either. Who needs books and teachers to corrupt innocent children when they can innocently corrupt each other and themselves? I’ve read fan fiction online.)

Mrs. Bergen’s speech doesn’t go over well, to Kate’s relief, and several other people talk. Then, one of the parents of a girl who was actually in the first grade class gets up and is dreadfully upset that they actually named male and female bodily organs in the class. The woman can’t even bring herself to say these words in mixed company because it’s so embarrassing, something that some of the other adults laugh at in the meeting. Kate senses that her mother is about to get up and speak, but she decides that she’d rather speak for herself. Kate says that she’s not embarrassed or ashamed by these words or by the book she read and that the words in question weren’t even in the book at all, the little kids supplied them themselves in a completely innocent way. Also, Kate thinks that it’s good for kids to learn the real, proper names of their body parts and not get embarrassed or ashamed like some adults, and if anyone wants to criticize the book, they really should read it all the way through, not just the one page with the birth. Kate’s impromptu speech is well-received and even Denise’s parents congratulate her.

The school board votes to allow the interschool project to continue with only one dissenting vote. It’s a victory for Kate, but there is something still bothering her. She knows that, while the dissenters are in the minority, her haters still hate her and are against her, and they’re still around, unpersuaded. They might be back to make trouble later, if they find the opportunity. Also, Kate has developed more of an ability to really see things from other people’s point of view with real depth (something she was unable to do even with Maudie at first). Now, she can think about how it would feel to be on the losing side of this conflict, and even to have a little empathy for Mrs. Bergen. She knows that she wouldn’t like to be in her position. Kate even starts to realize that there are limits to things like a person’s individual rights because, sometimes, those rights can encroach on another person’s rights. Where is the dividing line between having the freedom to say something and the freedom not to hear something? (Where is the dividing line to say what you want about another person and the freedom not to be bullied or have your name slandered? Where is the dividing line between freedom of association and the freedom to walk away from harmful relationships? What do you have a right to control or not control?) There is depth to these issues, and because Kate has matured through her experiences, there is depth to Kate’s thoughts about it. The world and other people are more complex than Kate has ever realized before.

Kate’s father says that all of these issues are complex, and there isn’t always a perfect solution. People just have to do the best they can to work things out as they go. Democracy is just like that.

My Reaction

I edited my review of this book from the way I originally wrote it because I wrote the first review more as stream-of-consciousness, and I decided that it was too awkward and difficult to follow. I left some of my reactions in the middle of the story summary because there were things that made more sense to discuss in the moment rather than trying to do a call-back to them later, but I decided to explain more of my reactions at the end of the summary.

I remember censorship and book banning were topics in children’s literature and tv shows when I was a kid. Generally, the opinion of those books and shows was that too much censorship was a problem, and there was a recurring theme in such stories that the people who were most vehement about banning books were the ones who had never read them and didn’t know much about what the books were really about. This particular book also has that element, but it goes deeper into the various motivations of people who are concerned about the content of children’s books and the varying degrees of concern they have. I thought that it also had some thoughtful insights into social maneuvering and the nature and behavior of cliques (much of which irritated me, even though I think it’s largely accurate, because cliques always irritate me), and some of it also ties into the nature of the public controversy about the book in the story.

Social Maneuvering and the “Right People”

Right up front, I have to explain that this book is about two major issues, but there’s a connection between them. The major issue of the story is censorship, particularly about sensitive topics presented to children. It’s an issue that still resonates today. In the early 21st century, there has been a revival of concern about certain issues in children’s literature, with an intensity and both legal and social consequences for people who tread too close to the edge that have children’s educators and librarians genuinely concerned for both their livelihoods, their own physical safety, and even that they may be sent to prison. However, this story closely examines the social consequences of being a controversial person or one who has been labeled as as someone outside the “right” kind of people. Beginning with the behavior of the girls in the story toward each other, the story examines how groups of people use their reactions to other people to bond with each other or solidify their own public image and promote themselves. What bothers me is that we see that type of social maneuvering echoed in the way the adults behave when the controversy over the book Kate read in class begins. It’s not just kid stuff; it’s people stuff, regardless of age.

This type of using other people for social maneuvering is a big pet peeve of mine. I’m very much against one-upmanship in all of its forms (and I complain about it constantly), so the way the girls in the story were trying to increase their own social cred and bonding with each other by putting down Maudie got on my nerves immediately and stayed on my nerves through the entire story. I personally consider it immature, but as someone who now qualifies as being considered middle-aged, I’m well aware that some adults don’t behave that much different from the way they did when they were young teens. Bowling for Soup made fun of that phenomenon in their song High School Never Ends (song and lyrics on YouTube – it also mentions sex – some adults are still as obsessed with finding out who’s having it with whom and what other people are saying about it as teenagers are):

“And you still don’t have the right look

And you don’t have the right friends

Nothing changes but the faces, the names, and the trends

High school never ends”

I talked about my annoyance with that throughout the story summary as incidents happened. I didn’t like Kate as a character from the beginning because she was an active participant in this without any self-awareness. Kate does improve as a character throughout the story, but it’s only after she’s on the receiving end of something similar to what she and her clique were dishing out. I was glad for the improvement, but it was hard to feel too much sympathy for someone who had previously been on the bandwagon with that.

The major issue hinted at in the title of the book is censorship, but that doesn’t actually come into the story until several chapters in (although the chapters aren’t very long). Before that, from the very beginning of the book, there is another issue about popularity and being part of the in-crowd, particularly that catty form of bullying so often found in schools and all too often afterward in workplaces because some people just never mature emotionally and socially. In particular, I noticed the misconceptions that develop around people because of this type of behavior. The concept of being friends with the “right people” especially bothers me. “Right” for what, specifically? In the beginning, Kate is worried about being popular, but she hasn’t stopped to think about popular with whom. As I pointed out in some of my reactions to the story during the summary, nobody on Earth is popular with absolutely everyone. Life is about making choices, and being in agreement or popular with some people very often means passing up connections with others at the same time.

Kate understands from the beginning that any friendship with Maudie means compromising friendship with her existing friends, who are against Maudie, particularly Jackie. What it takes her a long time to understand is that the same is true of being friends with Jackie. Jackie is mean, manipulative, and controlling, and being friends with her means shutting herself off from relationships with anyone who can’t stand the way that Jackie behaves and the way that Kate behaves in Jackie’s presence. Maudie indicates that’s the case when she has that honest conversation with Kate about how unfriendly people seem at their school, although Kate doesn’t get it at first.

Admittedly, I would never have had this conversation with Kate as a kid in middle school because I was the quiet, introverted type who more often watched others rather than speaking up, and I frequently made decisions without consulting other people about them, especially people I didn’t like. Maudie was trying to talk to Kate to give her a chance to be friends, but in all honesty, I would not have wanted to give Kate a chance as a kid. I wouldn’t have liked what I saw of Kate and her friends, and I would have seen that Kate’s behavior is completely intentional, so I would never have talked to her about anything if I could avoid it. It would have taken a great deal of effort to get along with people like that and, in real life, where there are no guarantees of a redemption arc, like in books and movies, the odds of all that effort paying off would be extremely low. People like that are the way they are because they like being that way, and more importantly, they get some kind of social payoff for it, so I wouldn’t expect them to change that and sacrifice whatever payoff they’re getting or think they’re getting just because someone who wasn’t part of the already-established “right” crowd was nice to them or honest with them. I would have completely written Kate off, and she would probably be too busy snubbing me to even notice that I was avoiding her, so it would probably never matter. She would think that she won by driving uncool me away, and I would be rid of her, so I’d win in the long run. Unless she changed and started being different, but I’d still rather skip associating with her until after that change happened because otherwise, I’d just burn out on her in a hurry.

In dealing with such a person in real life, I know that my existence wasn’t be the reason why she started acting the way she did in the first place, so having her in my life could never be the reason why she’d ever stop being like that, in the absence of another, more negative influence. In a way, the story illustrates my logic in this type of situation. Although she does change during the course of this book, it’s not really because of Maudie’s friendliness by itself. Maudie does present her with an alternate friend and a more positive influence, but what really turns Kate’s character is being treated in the way she has treated Maudie and seeing how awful it is, being gossiped about and treated as abnormal and “wrong” when she didn’t really deserve it. Kate just doesn’t get it in the beginning because nobody has ever treated her like she’s treated Maudie before and doesn’t have the imagination or empathy to figure it out without experience that type of hurt directly herself. What I’m saying is that, in a way, a person like her has to be hurt in that way to understand how it feels because they lack the ability to figure it out all by themselves. Maudie was offering friendship and positivity, but it wasn’t until she started experiencing the pain of the same type of negativity that she was dishing out herself that Kate had the incentive to accept those offers of friendship and more positive influences. If she hadn’t had that type of negative experience, I think it would have taken Kate much longer to make that type of change, or it might never have happened for her at all.

Really, when you begin to think about it, much of this story is about control, both the social aspects and the censorship ones. Kate comes to realize that she has the ability to choose her friends, that she has control over who she spends time with, and that she really would prefer to be with people who are kinder and less controlling of her than Jackie is. It’s Jackie’s attempts to control what Kate does and who Kate sees that begin to turn her away from Jackie, and as I said, I think that’s a valid complaint. The “right” people that Kate wants to be popular with in the beginning seem to be the ones who are in control of who is “in” and who is “out” and who associates with who, until she realizes that she doesn’t like that kind of manipulation and control, and she starts to see that there are other options outside of that negative, manipulative, and controlling group.

This talk about control and manipulation seems a bit dark, darker than the book actually reads, but there are some threads that run all the way through life, and the issues of the classroom do carry on to adulthood and into adult behavior. What kids learn in and out of the classroom shapes what they do and the kind of people they become because kids are all about learning how the world works and how to behave in the world to get what they want. The back of the book specifically talks about popularity and how the main character, for whom popularity is extremely important, has to learn to stand up for what she really believes in even if it’s not popular with everyone. Kate has to accept that she can’t always control how other people see her and how they talk about her, but she still has to learn to control what she stands for, how she expresses herself, what she is willing to do for the sake climbing the social ladder, and where her limits are.

Censorship and Control Issues

The censorship issues in the book are also about control. Some of it is about social control, from the way the adults start forming little groups and cliques around the issue of the controversial book, using their badmouthing of Kate and “dirty” books as a bonding issue among themselves, not unlike the way Kate and her friends initially used their badmouthing of Maudie for bonding purposes among themselves. Some adults appear to be using the issue as a way of controlling others and promoting themselves for attention. However, as the teacher and Jackie point out during the discussion in English class, some parents who are worried about the “dirty” book are coming from a place of fear, and it’s specifically a fear regarding their lack of control. The teacher points out that parents try to control their children’s reading material and media consumption because they’re trying to protect them from serious issues and the related consequences, while Jackie’s emphasis is on parents protecting themselves from uncomfortable thoughts and topics by trying to avoid confronting them with their children. I think all of these aspects of control are present in the situation in the book and in real life, to varying degrees in different people, but I also think that both real people and the characters are trying to control things that they don’t actually have the power to control, at least not completely. I think a better response than trying to control the uncontrollable is to develop an attitude of confidence in handling the unexpected and imperfect. Readers can disagree with this interpretation, if they wish, but that’s the way I read this situation.

There are many things in life that are beyond people’s control, from scary world events discussed on the news to unexpected health problems to the awkward things that six-year-olds blurt out in public about their body parts. Human beings do like to have a measure of control because that’s what helps them minimize disaster in their lives, from minor embarrassments to actual harm. I understand the desire for control and certainty. However, I also believe in limits.

I believe that there are limits on what people can control in their lives, whether it’s controlling circumstances or other people, and I think there should be limits on what people can do to assert control over their lives by controlling other people. Human beings are naturally limited creatures. We never have full knowledge of anything, and there some things in life that you just can’t change, like the fact that human beings have certain body parts, and some girls do look at their private parts with a mirror like Anne Frank did because they’re curious about what’s part of their own bodies, and it’s really the only way to do that. Hey, they’re stuck with those parts, and people with female body parts get periods, whether they like it or not. Simply having a physical human body with all the related bodily functions is just one of the many things that nobody can control. Nobody asks anybody ahead of time if they want their bodies to be the way they are. They just are, and as people grow up, they have to learn about what things are and how to deal with them because that’s how the world is. Their bodies will still have the same parts that work the same way, whether they know the names of them or understand their function or not, and everyone reaches a point where they simply can’t avoid knowing.

Denise’s father said that “it is impossible for even the most well-meaning teacher to know when the moment is right for every child in class,” but his assertion, although “well-meaning” itself, also contains a couple of assumptions that may or may not be true. First, is there really such a thing as one, single “right” moment to confront some of life’s realities? Maybe there’s a “right” time for that, and maybe there isn’t. Maybe there isn’t any such thing as a perfect moment, and maybe life is more of a series of moments and gradual learning opportunities. Some realizations don’t come all at once but in stages and steps, some planned and some not. The discussion in that took place in the class of first grade students could be considered one such step in the lives of the students, although the way it reads sounds like it was more of a revealing of the level of understanding that some of the young students currently had rather than a presentation of new information because much of the talk was volunteered by the students themselves.

Second, Denise’s father seems to be assuming that parents are able to tell when when the “right” moment arrives for their children and will act accordingly when it does, and as an adult with over 40 years of life experience, I know that isn’t true. I’ve known and known of girls who were surprised and terrified by their first period because their parents didn’t think that the “right” moment had arrived until after their little girl started bleeding and absolutely had to be told that they weren’t dying and didn’t need to go to the hospital. (See some of the recountings of first periods on the CVS website for examples. I know a couple of others from friends.) It’s hardly a magical, heart-warming “right” moment when it plays out like that. Not everything has to be done immediately, today, but that doesn’t mean that parents always make things better by waiting as long as they want to talk to kids about situations that are simply going to arise at some point, without prior warning. Time waits for no one. Maybe when the “right” time comes in children’s life, the adults around them will recognize it and act accordingly, with the right amount of preparation, and maybe they won’t recognize it or have difficulty accepting that the time has come, so they’ll lose the moment and the kid will panic or turn to someone else for the answers they need instead. That type of situation is what some of the kids in Kate’s English class discuss. They seem to be aware that they need to have some understanding of certain things eventually, even if their parents never reach the point of being emotionally comfortable with the concept of them having that knowledge or sharing that knowledge with them. What I’m suggesting is that we can’t always choose the “right” moment to deal with uncomfortable or difficult things. Sometimes, moments just come, and we just have to react as gracefully as we can, prepared or not. The reading of the puppy book and the kids’ questions about it are just those kinds of circumstances.

Even if the puppy book hadn’t sparked this particularly discussion among the first graders, it could have arisen just from seeing a pregnant woman somewhere or one of the kids talking about a pregnant relative or pet in class. Not everything in life can be controlled, and I had the feeling like some of the adults were trying too hard to control the uncontrollable. Adults talk about controlling the books kids read because books are relatively easy to try to control because they’re physical objects, neatly contained between two covers and can remain closed and unread, but the life moments that books portray are nowhere near that controllable. Seeing pregnant people or animals, getting a period earlier in life than expected, or hearing someone talk about something are just things that can happen with no prior warning, regardless of what anybody is reading at the time. In a way, I think that having a brief introduction to certain concepts from a book might take some of the shock value out of something that the kids later see, hear, or experience than if those same circumstances arise when they are completely unprepared.

I don’t think that facing the unexpected is the end of the world. Life happens, and when it does, it might not matter precisely how it happened or whether the timing was inconvenient as long as adults are willing to deal with whatever happens when it does, even if it’s awkward and uncomfortable and comes sooner than we think it should. Kate’s father says that all of these issues are complex, and there isn’t always a perfect solution. People just have to do the best they can to work things out as they go. Democracy is just like that, and so is just plain life. Life can be complex and unpredictable, but we still have to live it as best we can as we go.

Although I strongly believe that life isn’t something easily controlled and that the ability to respond gracefully to the unexpected is important, I do also agree that there are some limits on what children should be shown intentionally and that adults should give it some thought ahead of time. I don’t think it’s entirely a matter of maintaining full control over what children see or making it everyone’s responsibility to just accept whatever people give them and just deal with it, but rather a combination of both. It’s a delicate balance, and it’s rarely perfect, but I maintain that it doesn’t necessarily need to be perfect because dealing with imperfection is a valuable life lesson by itself. Rather than worry about those imperfections and being fully prepared for them, I think it’s more positive and productive to show children that the unexpected, awkward, and uncomfortable are manageable. Things can take us by surprise, and we don’t always get to pick our ideal moments, but we can still manage things, even if it’s a bit awkward, so there’s no need to worry about exactly how life is going to go.

My Racy Romance Book Story

Earlier, I mentioned that, when I was 10 years old, a friend took a racy romance book that belonged to her mother, read it, and told me all the most shocking parts. At the time, I knew what sex was, and I understood the nature of what my friend described, although I’ll admit that I didn’t actually know all the words used in the descriptions. That is, I had some knowledge, but the book was definitely not suitable for girls our age or at my level of understanding.

So, what was the effect on me from this incident? Probably not the one that most people would expected. I knew my friend was intentionally trying to be shocking and scandalous, so I said “Ew!” at all the expected places for what she was describing, but the issue that ultimately stuck with me from this experience was more about relationships rather than sex.

It’s a little hard to describe without telling you what the book was about. Let’s just say that the woman wasn’t satisfied with her husband because she was craving something more dangerous. (This is putting it mildly, but that’s the general gist of it. I can’t remember what the title of this book was, so I can’t tell you now or even look it up myself.) So, after being delightfully shocked and scandalized by this forbidden book, I started feeling sorry for the husband in the story.

From the pieces of the story my friend told me, he actually seemed like he was a pretty nice guy, and he was trying to do things he though would please his wife. He didn’t know how she really felt or what she actually wanted, and that struck me as unfair. Although the book was from the point of view of the woman, I found myself, even at age ten, really not liking her because I thought she was self-absorbed and unappreciative of the relationship she had. She seemed to be all about what she wanted and didn’t think she was getting, and I didn’t think she was looking at her husband as a person who also had feelings and was trying to make her happy. After the initial thrill of the shocking bits wore off, my impression of the characters and their relationship stayed with me. They didn’t have a good relationship.

It’s true that you don’t always know how things will affect other people, especially young children, and for that reason, I do think information should be presented gradually and with some caution. The reason why I’m telling this story is to point out that unexpected reactions aren’t always negative ones. My experience with this book was similar to the one I had with the book on witchcraft that I saw when I was around the same age. I learned about something I didn’t want (even though the characters in the book were married and having sex, their relationship didn’t look good, and I thought the woman’s priorities were messed up), and I learned that I can reject ideas that are unhealthy. A person who already does consider other people’s feelings and puts high priority on people’s welfare will continue to have those concerns. If you already have certain priorities or behavioral standards that fit with your personality, they don’t just disappear. Even if something new and shocking temporarily shakes them, they’ll come back. I’ve realized before that I have the ability to reject things I see that I don’t like, whether it’s a book or a relationship with another person that just wouldn’t be healthy.

My friend really shouldn’t have taken that book of her mother’s without permission. Maybe my friend’s mother shouldn’t have been reading that kind of stuff, or maybe the book has a better ending that redeems the characters. (My friend never told me how it ended. She just wanted to shock me with the scandalous parts.) Over 30 years later, I still have reservations about those characters and their relationship.

I wouldn’t recommend kids read books like this. Not all of them are going to have the revelations I had when I considered the characters’ relationship. However, I do think that a couple of positive ways to prime kids for moments like this, when something is unexpected sprung on them (no matter why or by whom) are to make sure that they prioritize people’s welfare and consider the feelings of everyone involved (including but not limited to their own) and that they understand that not everything people tell them is going to be a good idea and that they have the right to reject things that wouldn’t be healthy or helpful for themselves. If you understand that you have both the right and the ability to walk away from anything, you needn’t fear much about what others might unexpectedly offer. I’d also still recommend that parents make it a point to talk to kids about what’s going on in their lives and how they feel about things, so if anything unexpected arises, you can respond to it quickly. I do also highly recommend that parents read some of the books their children are reading and/or ask them about what they’re reading and how they feel about it. If you regularly discuss what the people in your life are doing and how they’re feeling, you don’t have to wonder and worry about it.

I think a dose of honesty is also a good idea. I don’t see anything wrong with parents admitting to their kids that something has come up unexpectedly and that they’re not sure that they’re explaining things in a way the kids will understand, but that they’re making an effort to help them understand what just happened or what people are talking about. (“This isn’t quite the way I was hoping you would start learning about these things, and I’m not sure if you’ll completely understand what I’m about to say, but since the subject has come up, there are a couple of things that I think are important for you to know about this … Now, I’d like you to think a little about what we’ve just talked about, and we’ll talk a little more about it later, after you’ve had time to consider what I’ve just said, and I’ve had time to consider what else I should tell you about that.”) There are some things you can do to prepare for life’s difficult issues and conversations ahead of time, and that helps, but I think it’s also important to acknowledge that no one is every 100% prepared for everything. That might feel a little scary at times, but at the same time, nobody has to be completely prepared for everything for everything in life. We can still manage if we’re willing to be open and honest and accept life as it comes, dealing with things in the moment as best we know how. Knowing that it’s possible to do that makes it a little less scary.