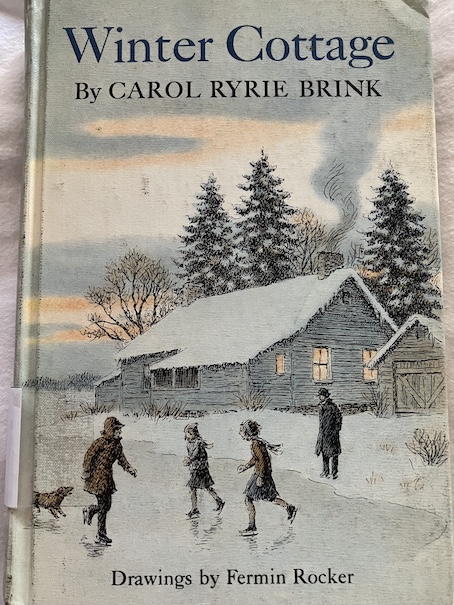

Winter Cottage by Carol Ryrie Brink, 1939, 1968.

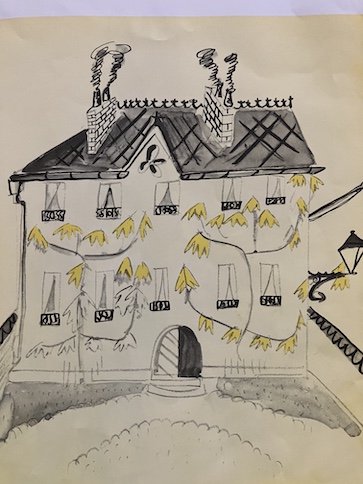

The Vincents own a summer cottage in Wisconsin. It was once an old farmhouse, so it is well-insulated and can be heated during the winter, but the Vincents only use it for about 2 or 3 months in the summer. The rest of the time it is empty and used by animals, like mice and woodchucks. However, that’s about to change.

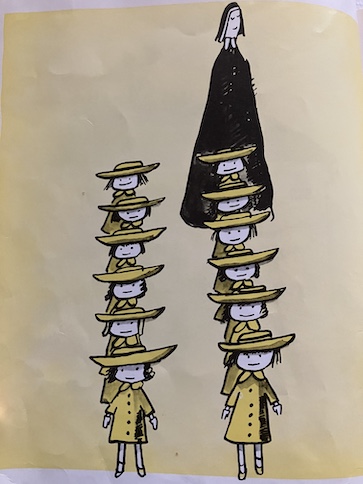

The year is 1930, the Great Depression has started, and many people are out of work and desperate to provide for their families. One such family, a father with his two daughters, happens to be passing near the Vincents’ empty summer house in the middle of October, when the Vincents have already long left the house, when their car suddenly breaks down. They were originally on their way to an aunt’s house to stay with her, but with their car broken down, they’re unable to continue their journey. Mr. Sparkes is a pleasant and easy-going man but impractical and a failed plumber. His eldest daughter, Minty, tends to deal with the practical aspects of things. Minty’s younger sister, Eglantine, called Eggs as a nickname, is the first to notice the empty summerhouse and suggests that, if they could get in, they could make some food. Needing a place to stay for the night and finding a window unlocked, they decide that they’ll go ahead and stay in the house. Although Minty has some reservations about staying in a house that belongs to someone else without their permission, she doesn’t have any better options, and she soon gets caught up in the excitement of exploring this unfamiliar house.

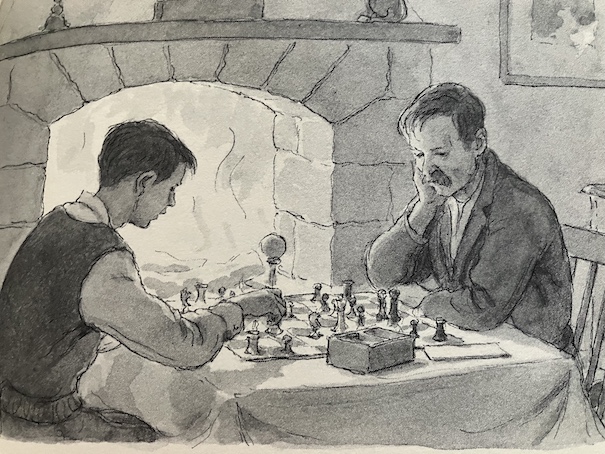

Mr. Sparkes feels like a failure because he’s been in and out of work, and typical jobs just don’t seem to suit him. Their Aunt Amy, the sister of the girls’ deceased mother, thinks that Mr. Sparkes is a failure and a silly, impractical man because he’s always quoting poetry, and his main talent seems to be making his special pancakes. There is some truth to what Aunt Amy says, and Mr. Sparkes acknowledges it. It seems like his only real talent is for making incredible pancakes, although his daughters reassure him that they love him and don’t see him as a failure. They were traveling to stay with Aunt Amy because they have no one else to stay with, but it’s clear from Aunt Amy’s letter that she isn’t looking forward to their arrival, and she also would not welcome their dog, Buster. Eggs says that she wishes they could just stay in this lovely cottage all winter, and Minty wishes the same thing, although she knows it isn’t really right for them to stay in this house without the owners’ permission. Mr. Sparkes likes the cottage, too, because it has a wonderful collection of books, including books of poetry.

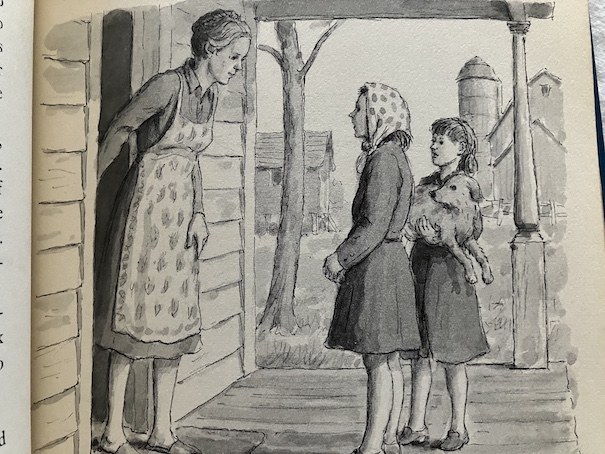

The next day, Mr. Sparkes tries to fix the car, but he’s a terrible mechanic. He takes the engine apart and doesn’t know how to put it back together. The girls go to a neighboring farmhouse and ask if anybody there knows anything about cars. Mrs. Gustafson sends her son Pete with the girls to look at the car, and he manages to put the engine back together again, but he isn’t skilled enough to figure out how to fix the original problem. He says that they had better call a mechanic in town to tend to it and that it would likely cost them about $10. The girls are worried because they know that’s about how much money they have left, and if they spend it all fixing the car, they won’t have enough left to buy more supplies and travel all the way to where Aunt Amy lives.

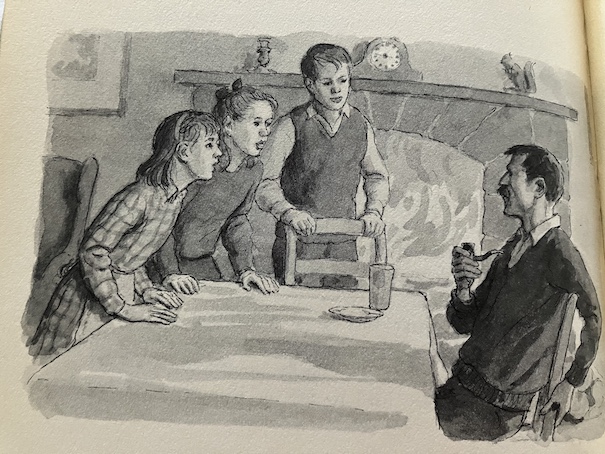

When they explain the situation to their father, Mr. Sparkes says that he thinks they should just stay in the cottage for the winter. Minty says that isn’t right because the house doesn’t belong to them, but their father says that it isn’t doing the owner any good to leave it empty all winter. To make it right, he suggests that they could rent it, so the owner would profit from their stay. The girls ask where he would get the money to rent the house, and their father says he doesn’t know, but he’ll have all winter to think of something. When they leave the cottage in the spring, he plans to leave the money in the cottage with a note, explaining why they stayed there. The girls are relieved that they don’t have to go to Aunt Amy’s house, but Minty is concerned that, by spring, her younger sister and impractical father will have forgotten all about the rent money for the cottage, and she makes up her mind that she will think of a way to get the money herself.

Eggs comes up with a possible way to make some money when she shows her father a contest magazine that she found at the last place where they camped. There are various contests in the magazine that offer prizes, like prizes for solving puzzles or adding the last line to a limerick. Mr. Sparkes is intrigued by the contests, and he says that they can pass the winter by trying them. He’s particularly interested in the contest to write a poem to advertise butter because he loves poetry and the prize is $1,000, which is an enormous sum to them.

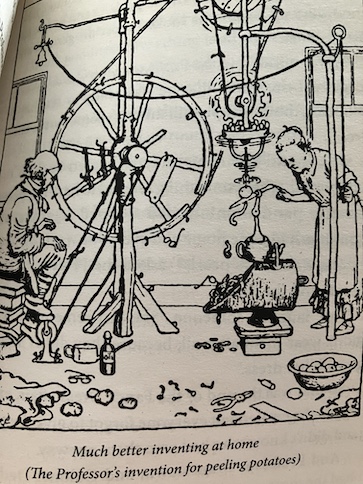

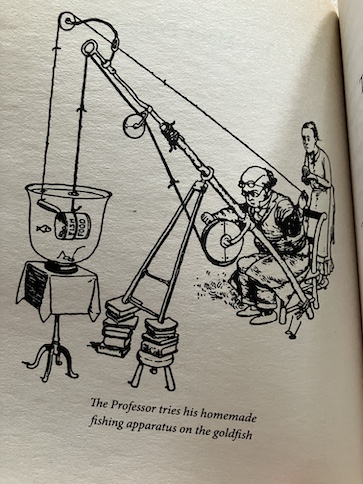

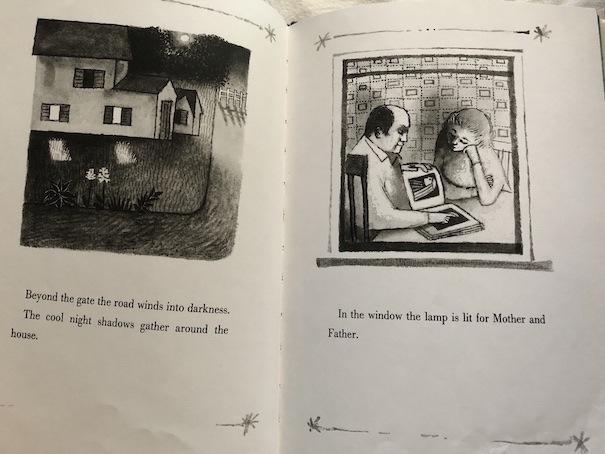

Life in the cottage is idyllic. They have some groceries with them to get themselves started, and their father enjoys fishing in the nearby lake for more food. The girls find nuts and cranberries, and their father cuts wood for the stove in the cottage. Minty takes charge of the house, making sure that they keep it neat for the Vincents. The girls learn that the Vincents are the ones who own the house and that they have a daughter called Marcia when they find some of Marcia’s belongings. Sometimes, Minty and Eggs think of Marcia as a friend, and Minty sort of idealizes her in her imagination. Minty likes to imagine the comfortable life she thinks Marcia lives, wherever her family lives in the winter, and she is determined that they won’t let her down by not taking care of the cottage or finding a way to pay the rent.

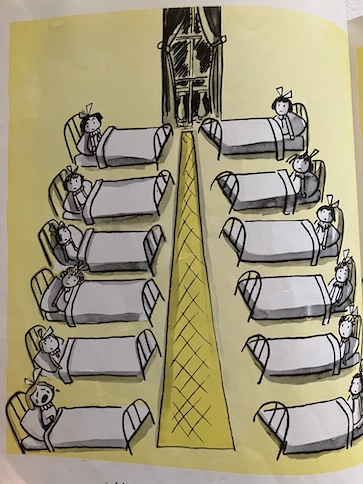

Then, Mr. Sparkes gets sick, and the girls are frightened because they don’t have much medicine and don’t know what to do. They try to get help from Mrs. Gustafson, but she’s away from home. As Minty is leaving the Gustafson farm, she happens to meet a boy who’s been hunting partridges, and in her desperation, she begs him for help. At first, he is surly and suspicious with her, but when he begins to understand the situation, he agrees to come have a look at her father. The boy, whose name is Joe Boles, is carrying a professional-looking medical kit and seems to know what he’s doing as he attends to Mr. Sparkes. The girls are grateful for his help, and they invite him to spend the night in a spare room in the cottage.

It turns out that Joe is also down on his luck. His father was a doctor, and the medical kit Joe carries used to belong to him. He gets his basic knowledge of medicine from his father and from his grandmother’s home remedies. Joe also wants to be a doctor, but he’s alone now and doesn’t know how he’s going to manage to get the medical training he really wants. Although he’s initially reluctant to explain how he came to be alone, he explains that his father was killed in a car accident. His mother is still alive, but she remarried to a man Joe can’t stand. Eventually, Joe just couldn’t take living with him anymore, so he ran away from home. Joe tells the family that he’s been camping in the woods. Running away from home may not have been the best decision Joe could have made, but he’s determined not to go back, and the family can’t criticize him too much because they’re also sort of running away and hiding out right now.

Joe seems to know what to do to help prepare the cottage for winter, and Mr. Sparkes says that they could use his help around the place. However, Mr. Sparkes admits to Joe that he can’t do much more for Joe than just give him a place to say for the winter, and a borrowed place at that. Joe says that’s fine, and he would like to stay with them for the winter, and he would be willing to pay for his room and board with his labor. The Sparkes family is thrilled to have Joe stay with them and help them. The only point that Mr. Sparkes insists on is that Joe write a letter to his mother to tell her that he’s safe so she won’t worry about him. He says that Joe doesn’t have to be specific about where he’s staying right now, but he knows that Joe’s mother will feel better, knowing that he has somewhere to stay for the winter.

With Joe, Minty and her sister explore the area more and visit the nearby Indian (Native American) reservation. Eggs is a little nervous about the Indians (the term the book uses) at first, worrying about scalping, but Joe tells her not to worry and that the locals are just curious about them. Joe worries less about people recognizing him as a runaway in the reservation village than in the town nearby because it’s a little more remote, although they do accidentally meet the local sheriff in the reservation store, who recognizes Minty from an earlier shopping trip to town. Joe does his best to stay inconspicuous.

While they’re in the reservation store, they learn that the reason why the sheriff is there is that the storekeeper’s son is in trouble. The son, who is a young man in his 20s, got drunk, broke into somebody’s house, ate some of their food, and fell asleep in their bed. The young man’s father argues with the sheriff that the son didn’t actually steal anything from the house, but the sheriff says that what he did was trespassing and that it’s illegal to break into someone’s house, stay there, and use their things without permission. He says that, for that charge, the son will have to spend a week in jail. This incident is troubling to Minty because she knows that she and her family also don’t have permission to use the house where they’re staying, and they’ve been there longer than this young man was in the house where he trespassed. When the sheriff points out that the weather is getting bad and offers to take the kids home, Minty panics at the idea of him finding out where they’re staying and tells him that they plan to spend the night at the reservation.

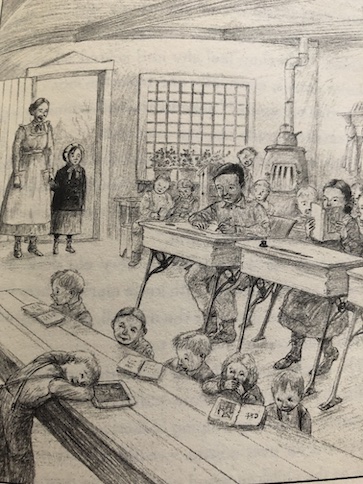

Of course, the kids don’t really have a place to stay on the reservation, and the weather is bad for camping. They are rescued by the village priest, who says that Joe can stay with him, and the girls can stay with Sister Agnes, one of the nuns who runs the mission school on the reservation. (“Indian schools” like this have a rather scandalous reputation these days for reasons I can explain below.) Minty says that they don’t have any money to pay for a place to stay, but Sister Agnes says that doesn’t matter because “God is your host.” In other words, they’re offering the children a place to stay out of kindness and Christian charity and don’t expect payment. There are some Native American children who also board at the school, some because their houses are too far away for them to travel back and forth between home and the school daily and a couple of children who are orphans and live at the school full time.

There is a scene where some of the Indians are playing drums and dancing, but not the ones living at the school. One of the nuns says that the dancers are “heathen Indians” and that “our Christian Indians don’t dance,” although Minty can tell that the Indian students at the school are feeling the rhythm of the song and enjoying it. Joe takes Minty and Eggs to see the dancers, and they find it fascinating. I didn’t like the “heathen” talk (although I think it’s probably in keeping with the historical setting of the story), but I did appreciate an observation that Minty makes, “Indeed it seemed to be a not entirely un-Christian gathering, for here and there among the gaudy beads was the gleam of a cross on the neck of some forgetful dancer.” That observation contradicts the idea that the dancers aren’t Christians because at least some of them seem to be. That and Minty’s observation that the girls at the school were interested in the dancing and drumming but were being careful not to show it hints at more complex feelings and social dynamics in this village. The people who run the school have some strong opinions about how proper Christians should act, but the Native Americans are still maintaining some traditional practices, and some people are walking a fine line in what they practice and believe.

One of the Indian girls at the dance invites Eggs to join in, and she does. Minty finds that amusing, and Joe tells her to let Eggs have fun because she’s enjoying herself. Sister Agnes asks them later if they enjoyed the dance, and Eggs says she did. Eggs later says that it seems like they don’t have much to do on the reservation, with no “picture shows” (movies) to see and not many toys, so she thinks that the dancing is part of their entertainment. Sister Agnes says, “They are heathen, but God will forgive them.” Minty isn’t too concerned about whether or not the dance might be “heathen” or sinful, but what Sister Agnes says makes her think about what God must think of her family for living in someone else’s house. She hadn’t given it much thought before, but she knows God must know what they’re doing, even if nobody else does, so she prays that He will forgive them, too, and thanks Him for being their host. Before they leave the reservation the next day, a girl Eggs befriended gives them a basket of wild rice, and Eggs give the girl her doll in trade.

When the kids return to the Vincents’ cottage, Mrs. Gustafson is there, visiting with Mr. Sparkes. Mrs. Gustafson seems to accept the idea that they’re renting the house from the Vincent family, although Minty is nervous when she mentions that she writes to them sometimes. Mrs. Gustafson also warns them to beware of strangers because, sometimes, gangster and criminals hide out in the isolated cottages in the area when things get too hot for them in Chicago. Joe has heard stories about that, too.

When the family starts getting replies to their contest entries, the results are disappointing. Many of the contests have catches because they expect entrants to buy things or subscribe to things. There is another contest that they hear about on the radio from a flour company, offering a large cash prize for the best breakfast recipe. Minty thinks that sounds better than any of the other contest options because of her father’s wonderful secret pancake recipe, although her father has become disillusioned with contests. They don’t have much time left to enter that contest, and Mr. Sparkes is reluctant to share the secret recipe. The kids end up spying on Mr. Sparkes to learn his recipe so they can enter the contest on his behalf.

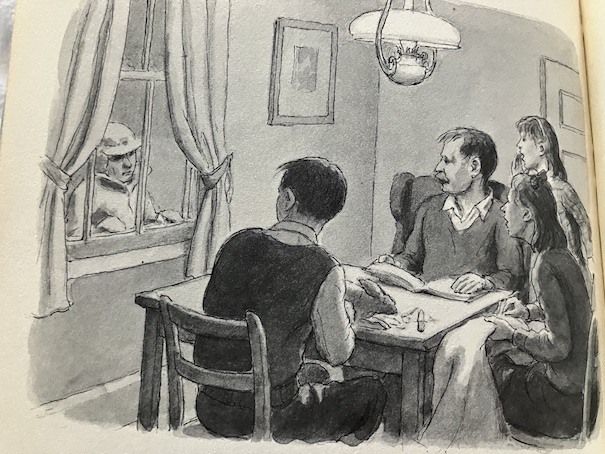

Then, one night, they see a man lurking outside the cottage in a blizzard. Minty warns her father not to let the man in, remembering Mrs. Gustafson’s warnings about criminals hiding out in the area and how they shouldn’t open the door for strangers. However, Mr. Sparkes worries about anyone who might be lost in the blizzard, and he has the children invite the man in. The man has a young girl with him, who is half-frozen and dressed as a boy, for some reason. When Minty realizes that the child is a girl and not a boy, the girl asks her not to tell anyone right away. Minty can tell that there’s something strange about this father and daughter pair, and it makes her uneasy. Then, Minty hears a report on the radio about a stolen car and a reward for information leading to the thieves. Is it possible that this man and his daughter are the ones who stole the car? Minty might consider turning them in for the reward money that her family badly needs, but with the blizzard, they’re now trapped in this cottage with this strange man and the girl. The girl, who goes by the name Topper, is fun and good at planning entertainment, but can she or her father really be trusted?

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive.

My Reaction

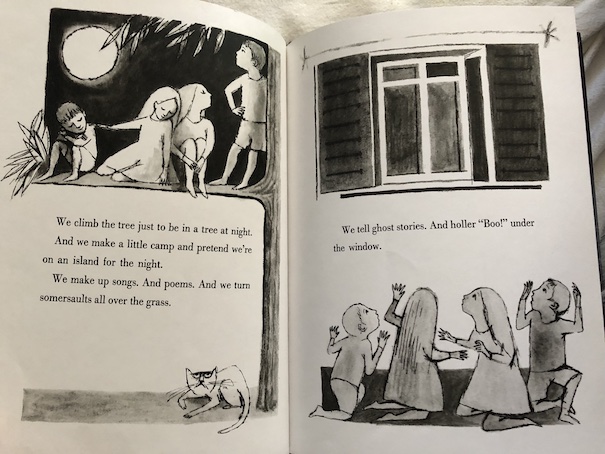

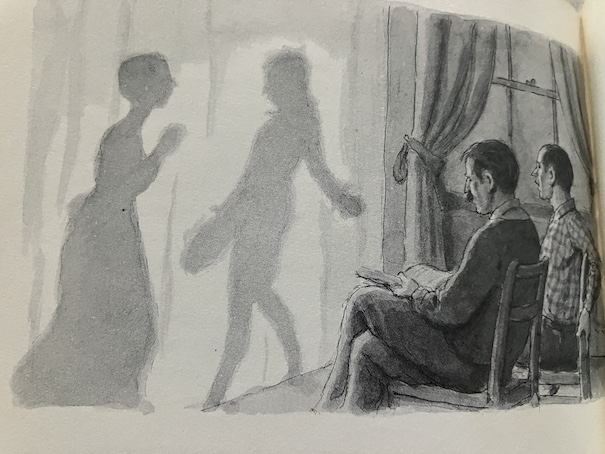

This book isn’t a Christmas story, although the title and some of the themes would have set it up well to be a Christmas story. It fits well with cottagecore themes, with the family, down on their luck, staying the winter in a cozy cottage and getting by as well as they can, enjoying simple pleasures. There’s a line in the story that I particularly liked, toward the end of the book, when the children put on a shadow play for their fathers:

“What a lot of fun you could have, Minty discovered, if you made unimportant things seem important and went about them with enthusiasm!”

I think that sentiment embodies the spirit of cottagecore. To really enjoy some of the simple pleasures of life, you do have to put yourself into the mindset that you’re going to enjoy them to the fullest! I read a book about Victorian parlor games that said something similar. A lot of old-fashioned entertainment and games are quite silly when you analyze them, but if you just throw yourself into them whole-heartedly, they can be great fun!

The family in the story is down on their luck and has their troubles, but their stay in the winter cottage is still an adventure, and they enjoy it. Their consciences do trouble them throughout the story because they’re aware that they’ve been using the cottage without permission of the owners. Minty in particular considers the morality of their actions and has a desire to make things right with the owners of the cottage. Fortunately, the story ends happily for the family, with their lives changed for the better. The people who own the cottage find out about them staying there, but they forgive them, and Minty finds a way to repay them for letting them stay.

Native Americans

The part of the story that I think is most likely to cause controversy for modern readers is the part where the children visit the reservation and the mission school. “Indian schools” have a sinister reputation in modern times because of their harsh treatment of their students and deliberate attempts to eliminate Native American culture. In the book, the nuns at the school make it clear that they don’t approve of traditional Native American practices, like the dance the children watch, because they don’t consider them to be Christian. They call such practices “heathen.” Their focus on discouraging their students from participating in traditional cultural practices is based on religious differences and a desire to convert people strictly to Christianity. However, I appreciated that Minty and the other children see both sides of the story and that Minty observes that some of the Native American dancers are wearing crosses, showing that the actual beliefs among the Native Americans are more nuanced than the nuns’ attitudes suggest.

This part of the story has some use of the word “squaw“, which is problematic because it has vulgar and derogatory connotations. The exact definition of the word varies in different Native American languages, but because it is considered vulgar and derogatory, modern people avoid it. At the time this story was first published, in the mid-20th century, many white people had the idea that “squaw” was sort of a generic word for women among Native Americans and didn’t realize the more vulgar side of the word, which is why it appears in some old children’s books, like this one. The word isn’t meant to be intentionally insulting here, although modern readers should understand that this word isn’t polite or appropriate. Apart from that, I appreciated how the main characters, especially Minty, see some of the prejudiced ways people, especially the nuns at the school, look at the Native Americans and their traditions and their realization that there are sides to their culture and practices that the adults have overlooked.