In Spite of All Terror by Hester Burton, 1968.

This story takes place during World War II and focuses on a child evacuee from London. The title of the book comes from a quote from Winston Churchill:

“Victory at all costs, victory in spite of all terror … for without victory there is no survival.”

Winston Churchill, May 13, 1940

It’s September 1939, and Liz Hawtin is an orphan living with her aunt, uncle, and cousins in London. Her mother died when she was a baby, and her father was killed when he was hit by a car a few years earlier. Liz’s overbearing aunt is making her life miserable and has been since she moved in with her relatives. It takes Liz some time to realize why her aunt doesn’t like her, but it has to do with social class, political philosophy, one-upmanship, and her aunt’s sense of fairness and entitlement – what sort of people are “deserving” and what sort of people aren’t.

The main problem is that Liz’s father was into socialism before he died. In fact, he used to give public talks about it, and Liz would watch them as a child, although she admits in hindsight that she doesn’t entirely agree with everything her father believed. One value that she and her father definitely shared was the belief that education is important. Liz’s entire family is working class, including her father, and none of them have ever had more than just very basic education. Her father was a very bright man, but like other members of their family, he had to leave school early and get a job because their family was poor. However, he urged Liz to study and get the best education she could because he realized that higher education is the way to move up in the world and get better jobs and a better position in life.

Liz’s current situation when the book begins is irritating to her aunt because Liz has both the academic potential to attend a better school than the ones her own children have attended and because Liz’s father had the foresight to take out an insurance policy on his life that has provided Liz with enough money to attend this better school and to buy good school clothes and the extra equipment and books that this better school requires. Every time Liz has needed something for school, her aunt gripes about how much it costs and what a waste of time and money it is. Liz gets her aunt’s permanent wrath by telling her straight out that the insurance money belongs to her and not her aunt and that it was meant for her education. This enrages her aunt because she had labeled her father as the foolish, idealistic socialist who was undeserving, so the idea that, because of him, Liz has both academic aptitude and the money to support her education seems supremely unfair to her. On some level, she probably realizes that Liz’s more advanced education will probably help her to be more prosperous than the rest of the family, and she hates it and is jealous. She takes every opportunity to criticize Liz and to tell her that her time spent reading and studying is wasteful. She encourages her children who, like other members of their family, all have to leave school early to get menial jobs, to give Liz a hard time. The only members of the household who like Liz are her gentle cousin Rose and her uncle, but it’s difficult for them to stand up for Liz and help her because the aunt bullies both of them as well.

At the beginning of the story, Liz is fifteen years old, and she is faced with a difficult decision. She is getting close to graduating from her grammar school. She badly wants to finish, but she knows that the insurance money is running out. Soon, she will be faced with the difficult decision of whether to leave the school without graduating and get a job, which is bound to be the menial work that her cousins are doing. Her aunt has always resented her and is eager to get rid of her, so she wants Liz to get work and start supporting herself as quickly as possible.

When World War II breaks out, Liz’s life is changed forever, and Liz realizes that, ironically, the changes are going to be for her benefit. Because Liz is still a student, she will be part of the government’s program to evacuate children from London to protect them from bombings. None of her cousins will be evacuated, even though they’re not much different in age from Liz, because they are no longer students, but Liz will be sent to the countryside with the rest of the students at her school. The government will also provide money for her support and education during the period of the evacuation, so Liz realizes that she will be able to finish her education after all. Rose and Liz’s uncle are sad at her leaving, but her aunt makes it clear that she is pleased that Liz will be leaving very soon and that she doesn’t want Liz to come back after the evacuation period is over. Once Liz is finished with her education and no longer part of the government program, Liz will be on her own in the world. It’s both a little scary but also liberating for Liz. She doesn’t know where she will be staying during the evacuation, but at this time in her life, it’s really better for her to leave her aunt’s house, finish her education, and establish an independent life.

Before she leaves, she says goodbye to her grandmother in London. She worries what will happen to her grandmother, her uncle, and Rose when she’s gone. Her grandmother isn’t worried for her own sake because she’s lived through war before, and nothing ever seems to happen to her. Besides, she knows where the shelters are for safety, and she’s sure that she can take care of herself. Liz knows that, once she is gone, her aunt won’t be able to pick on her all the time, and things are bound to get worse for her uncle and Rose, but there’s nothing she can do about that.

When she arrives at school, she and the other students are told that they are being sent to a small village called Chiddingford in Oxfordshire. It’s such a small town that it doesn’t even appear on the map in their school atlas. There, they will be staying in the homes of people living in the village. The headmistress reminds them all that this will not be an easy experience for them. Many children are being evacuated along with them, and all of them will experience homesickness and difficulties adjusting to the place where they will stay. She urges all of them to be kind to each other and considerate of their hosts in Chiddingford. The girls in Liz’s form (grade) are also going to be paired up with girls in the lowest form because these younger girls are new to the school and don’t even really know each other yet. The headmistress thinks that the experience will be easier on them if they have an older girl as a buddy, like an older sister. Liz pairs up with a shy girl named Veronica, who is wearing a school uniform that is way too big for her. Her parents were trying to save money by buying her a uniform that she could grow into. It makes Veronica a laughingstock among the other students, but Liz sympathizes with her, knowing what it’s like to worry about money and to feel different from everyone else.

The students are excited by their trip into the countryside. The village of Chiddingford is already expecting them, although they had originally been told that they would be hosting a boys’ school instead of a girls’ school. Lady Brereton’s daughter-in-law asked her to pick out a boy from the arriving students who would be a good companion for her sons. However, since there are no boys on offer after all, and she knows little about girls, having only a son and three grandsons, Lady Brereton decides that she’ll pick out a girl from the evacuees in the same way she would pick out a dog, which is something she does understand. She chooses Liz because Liz has an alert expression and stands with her head up and a look of spirit and resilience.

Liz finds the move to the countryside disorienting, although she likes the peacefulness of it. Her reception at the Brereton house is disappointing because Mrs. Brereton had her heart set on getting a boy. She has three sons and is single-mindedly devoted to them. A girl simply wouldn’t do as a companion for her boys. In fact, she thinks that having a teenage girl in their house might well lead her teenage sons astray. However, people are commanded by the government to take in evacuees, and Mrs. Brereton can’t just give Liz back or trade her for someone else just because she’d rather have a boy. It’s awkward for both of them because Liz knows that Mrs. Brereton really doesn’t want her and that she tried to get rid of her.

Mr. Brereton is an historian, and he once worked at a college near Liz’s old neighborhood. He describes the history of the area and the type of housing there to his sons. The Breretons are a genteel, highly-educated family. They’re also the sort of intellectuals Liz’s father used to disparage, the ones who came to the college in their area and observed their lower-class living like scientists watching an ant colony and would leave, thinking that they understood their lives, when they had only ever seen them from the outside.

The youngest of the Brereton boys, Miles, makes fun of Liz when he finds out that her school doesn’t teach Latin because he says that she’ll never be able to go on to university. It stings because Liz is more educated than the rest of her family and is proud of it. She angrily retorts that she doesn’t want to go on studying forever because she wants to do something that will help win the war. Unknowingly, she’s prodding a sore point in the Brereton family because the eldest boy, Simon, wants to enlist, but his family would rather that he continue his education at Cambridge and become a doctor. Simon does want to be a doctor, but he also feels called to aid the war effort. He feels torn because his family is telling him that he should let others take care of the war while he goes to school and learns something that will make a difference later, but he feels guilty for staying out of it. His grandfather, Sir Rollo, who was a brigadier general, says that 19-year-old Simon is a man now and must make up his own mind about what he wants and what he’s going to do. Liz wishes that she hadn’t said anything about helping the war effort because she didn’t know that it was a sore point for this family, and she certainly wouldn’t want to influence Simon to do something that was dangerous or wrong for him. He seems too gentle and intellectual to really be a soldier.

When her teacher, Miss Garnett, comes to check on her, and see how she’s doing in the Brereton house, Liz says that she doesn’t think she fits in with this family. Miss Garnett advises her to give it time. Liz realizes that the Breretons are a tempestuous family, and it’s not really her fault for setting them off. They get set off by other things and people, too. Liz’s family back in London wasn’t the nicest, and they had their fights and spurts of meanness, but Liz feels like the Breretons are more unpredictable. She doesn’t know their history, quarrels, and sore spots, so she has no way of knowing what will set them off next.

Liz feels a little better after talking to the other girls from her school, comparing their host families. As she describes the Breretons to her friends, their absurdities jump out at her, making the whole situation seem more humorous instead of tragic. Mrs. Brereton doesn’t want her, which is hurtful, but she’s stuck with her anyway, which is funny. Young Miles keeps teasing her about not knowing Latin by shouting random Latin words at her, which don’t even make sense when translated. Miles is learning Latin vocabulary and can conjugate verbs, but he doesn’t really speak it as a language. Mr. Brereton, the professor, reads in the bathroom, which is the girls say is pretty normal, but what he reads are heavy historical texts, and he keeps a notebook and pencil in there, too, so he can take notes. The other girls laugh at the silly habits of the Breretons and tell Liz about their own host family. Three of them are sharing a room over a local shop, and the family that keeps the shop are certainly not intellectual. They have no books at all in their house, and they seem to be slow thinkers, who have only “one thought about every two hours.” Liz, whose source of pride back in London was being more educated than the rest of her family and most of the people in her working-class neighborhood, realizes that the Breretons’ higher intellectualism has been making her feel inadequate, like just a silly school girl. However, she and her friends are really more in the middle, doing better than some people, if not as well as others, and that’s not a bad way to be. Their learning isn’t over yet, either.

There are also some consolations to life with the Breretons. The live in an old, converted mill, and Liz has her own room next to the wheel house. Mrs. Brereton thinks of it as a rough room, very simply furnished and really more suited to a boy than a girl, but Liz likes it and is grateful that she doesn’t have to share a room with anyone else. When she doesn’t want to talk to the Breretons, she can go to her room to be alone and read, burying herself in Pride and Prejudice and other books she enjoys. When Miss Garnett sees Liz’s room, she also thinks it seems fun, and the water sounds from the millstream and waterwheel remind her of being on a ship.

There is one other member of the family that Liz hasn’t met yet, the Breretons’ middle son, Ben. Ben is 17 years old, and from the way his family talks about him in his absence, he’s something of a disappointment to his parents. Although he is two years older than Liz, they are about the same level at school, which is hard for his rigorously intellectual family to accept. He also has a tendency to get into various scrapes. None of them are truly shocking, mostly ridiculous teenage escapades. Liz knows that she’s seen much worse in her old neighborhood in London, but Ben’s family disparages his foolish and embarrassing behavior.

The reason why he isn’t there when Liz first arrives is that he’s taking a bicycle tour of Wales. His family starts to worry about him because he doesn’t return when he was supposed to. Then, they get a call that explains his latest escapade. In a wave of patriotism because of the starting war, he tried to enlist in the RAF, even though he was underage. At the recruiting office, he tried to avoid telling the recruiters much about himself, so they wouldn’t know that he was really too young, but he forgot that he wrote his name and address on the outside of his kit bag. The recruiters contact his parents and send him home. It’s the sort of well-meaning but thoughtless mistake that Ben often makes. His parents again disparage his thoughtlessness, and Miles makes fun of him, but Simon angrily tells them all off. He says that he understands Ben’s feelings of wanting to make a difference. Even if what he tried to do was clumsy and not well-thought-out, it was still noble. The grandfather of the family says that he and their grandmother certainly won’t make fun of him when he returns home. Liz gets the feeling like Ben might be more her kind of person than the other Breretons.

Liz and Ben get along well with each other when they meet. Liz learns that the room where she is staying used to be Ben’s art studio. Liz feels badly that she’s taken his space, but he tells her that it can’t be helped. He tells her that he wants to be an artist, although his parents disapprove. His mother doesn’t think that it’s possible to make a living off of art, and his father doesn’t think his paintings are any good. Because his father is an historian and an intellectual, he thinks of art in terms of fine art. He had another professor he knows, an art expert, take a look at Ben’s work, and he didn’t think much of it, so Mr. Brereton concluded that his son had no art potential. Ben’s family whitewashed over all the artwork he did on the walls of his studio before Liz arrived. Liz thinks this is terribly unfair because there are many different styles and tastes in art. Just because Ben’s father and one art critic didn’t like Ben’s art doesn’t mean that he doesn’t have talent. Ben is still determined to be an artist in spite of what his parents say. He and his brother Simon are very close and understand each other because neither of them quite fit their parents’ expectations and have different priorities from their parents. Liz understands how both of them feel because her family also never understood her or supported what was important to her. She comes to view both Ben and Simon as brothers and enjoys spending time with them. Ben takes her out on the river in the family’s punt, and during the winter, he teaches her how to ice skate.

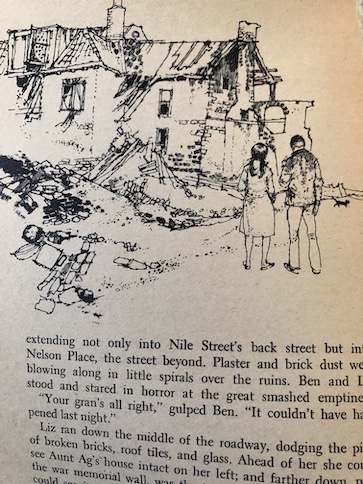

The book continues through the next year and a half, through the developments of the war and the lives and education of Liz and the Brereton boys. Although Mrs. Brereton didn’t initially want Liz, the Breretons become fond of her as she shares in their lives, and they come to understand one another. Each of them finds a way to make a difference in the middle of war, and through the hardships they face together and their shared lives, they become a family. When Liz gets a letter from her grandmother that lets her know that Rose is “in trouble” in London, she and Ben make a daring trip into the bombed city to rescue her cousin. The book ends at the beginning of 1941, just after the New Year, with the war still going on, but by that time, each of the young people in the story has found a direction in life and hope for the future.

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive (multiple copies). Because of the themes and some of the language in the story, I would recommend this book for teens and young adults. There are descriptions of bombings, war deaths, a teenage pregnancy (Rose, not Liz), and some mild swearing in several places. The violent parts aren’t as graphic as some descriptions I’ve seen in other books, but there is definite violence and death, so it’s not really a book for young children.

My Reaction and Spoilers

The Atmosphere

This story could fit well with both the Cottagecore aesethic and Light Academia. In the countryside, Liz is living in an unusual, atmospheric house, a converted mill, and the descriptions of her room sound enchanting! In some ways, the beginning of the book reminds me a little of Anne of Green Gables: an unwanted orphan who is taken in by a countryside family that originally wanted a boy, and a girl who loves books and is determined to pursue an education and make something of herself. Liz is a true book lover, and the story mentions the books that she reads and loves, like Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen, Jamaica Inn by Daphne du Maurier, and Beau Geste by P. C. Wren. Liz doesn’t just read because she is required to read for her classes but because she really enjoys books. She also comes to understand things from books she reads, like the war around her and the feelings of some of the Breretons from reading Shakespeare’s Henry V. The insights that people gain from reading are part of the reason why literature is regarded as one of the disciplines of the humanities, the areas of study that provide insight into human nature and human potential. Liz combines the insight and knowledge she gains from reading and what she perceives around her to better understand the world and other people. In some ways, she fits a little better with the intellectual Brereton family than she thinks she will at first.

Later in the book, after Liz has seen more of the war directly, she wonders if there’s really a point to continuing her education or if she should just try to get a job in a factory and do her part. Studying things like poetry and Shakespeare in class just feel pointless and irrelevant in the face of the larger, life-and-death events happening around her. She could relate to the themes in Henry V, but Romeo and Juliet begins sounding pretty silly to her. Her teacher persuades her to continue her education, telling her that the more educated she is, the better she will be as a worker and an asset to her country. At first, Liz doesn’t see how, and her teacher explains that she is learning mathematics, which are used for the construction and calibration of weapons. She is also learning biology, which would be useful if she becomes a nurse or has to care for someone who is wounded. As for things like poetry and literature, anything she studies will teach her humility and give her mental maturity and greater understanding of other people – the goals of the humanities. We don’t know about all of her long-term career goals by the end of the book, but along the way, Liz continues her education, takes on part-time jobs, and finds ways to help the war effort and the people she loves.

Evacuees, Social Class, and Socialism

The experiences of the evacuees in the story are very realistic. It’s important to note that child evacuations went in waves throughout the war, and Liz and her friends are part of the very first wave of Operation Pied Piper. When the war started, people expected that bombings would start almost immediately, which was why they tried to hurry as many children out of London as fast as they could. However, the book covers the real events and attitudes of the early war years, including the fact that the bombings didn’t begin as quickly as expected. When the bombings didn’t start right away, people started to think that the fear of bombings was an overreaction, and many families brought their children back to London from the countryside. Some called this phase of the war the “Phoney War” because people on the home front didn’t feel like there was a war really happening yet, and even on the front lines, there was relative quiet because the large scale operations hadn’t started yet. Liz feels more alone in Chiddingford when some of her friends from school return to London and leave her behind in the country. Liz knows that there’s no point in going back to London herself because her aunt won’t want her, and remaining with the evacuation program will allow her to finish her education. Of course, readers know that the Blitz is coming before the characters in the book do, and the people who returned to London will probably end up regretting it.

In real life, some of the children who returned to London prematurely were killed in the coming bombings, and others were sent away again in the next wave of evacuations. In the case of the kids in the story, Liz’s friends Annette and Naomi return to London, thinking that the risks of bombings were overrated. After the bombings start in the Battle of Britain, Liz’s grandmother writes to Liz and says that Naomi has been sent away again, this time to Wales, which was a destination for many evacuees. We never hear what happens to Annette.

The book did a good job of showing how evacuees and their host families experienced some awkwardness with each other because of their different lifestyles and social classes. Not only is Liz not from an intellectual family like the Breretons, but she also comes to realize that she lacks some of the table manners and social graces of people of their class. The book also explains how Liz and her friends speak differently from the Breretons. Liz and her friends are described as being “bilingual in two kinds of English.” When they’re with family and friends, they speak cockney English, but at school, they speak a more “posh” version of English. However, even their more “posh” English isn’t as high class as the way the Breretons speak because they are a family of people who have been to boarding schools and have higher levels of education. You can hear what a cockney accent sounds like, how it works, and the social significance it has from these videos:

- 1976: COCKNEY accents from the BCC Archive (about 11 min.) – The people talking would have been alive during WWII, some of them probably around Liz’s age at the time. Some of them talk about the differences between the way they talk and how younger generations speak.

- A LONDONER Explains How to Speak COCKNEY (about 13 min.)

- The Story of COCKNEY the (London) Accent and its People (about 35 min.) – Explains more about the social history and cultural identity of Cockney people. This includes some of the historical information that Mr. Brereton, history professor, could recite, although Liz knows that doesn’t mean that he fully understands the realities of day-to-day life in the East End. Toward the end of the video, at about 27 min., there is a clip from a 1930s film as an example of how the accent used to sound because accents change over time.

The Breretons are using “received pronunciation” (RP), which is called “received” because people in England don’t tend to speak that way until they are taught to do it in the higher-class schools. It comes directly from having an education, particularly a higher education, so people who speak that way are immediately announcing their social class and education level with the way they speak. You can hear it and get an explanation of how it works from these videos:

- Make Do and Mend (about 3 min.) – A 1940s educational film about making and mending clothes, to save on material for the war effort. Received pronunciation (RP) is also sometimes called “BBC pronunciation” because this is the accent that radio announcers would use. The announcers in this short film, one male and one female, are using 1940s RP.

- 1967: John REITH explains the “BBC ACCENT” (about 10 min.) – From the BBC Archive, about why the BBC particularly wanted its announcers to speak RP. John Reith was the Director-General of the BBC, beginning in the 1920s and ending in the late 1930s. During WWII, he became Minister of Information, and from there, moved to various other governmental roles. This interview was his very last appearance on television. It took place when he become Lord High Commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. The interviewer asks him about the reason why, during his BBC years, he wanted his broadcasters to speak with an RP accent. Basically, the logic behind RP was to put more emphasis on education and ability to communicate clearly rather than the speaker’s regional origin. Particularly in radio, where listeners only have the voice to rely on and no visuals to clarify anything, it was important to have an accent that would be as clear as possible to the general population, where there would be no confusing regional pronunciations and slang. In the video, John Reith specifically says that they didn’t want there to be any accents that would seem comical or irritating to the listeners by seeming overeducated, undereducated, or too regional. They also debate the social implications of this and the effect of television, which was relatively new technology to them in the 1960s. Both of the men in the video are speaking a kind of RP, although they’re not completely the same as each other. John Reith admits that his speech still has regional influences because he’s from Scotland.

- The RP English Accent (about 9 min.) – About who speaks RP, how it sounds, and the social implications. It also mentions how there are people, like the presenter, who speak a kind of RP but still with regional influence, which is similar to the way Liz and her friends are learning to speak in their school. It also discusses how WWII changed the way this accent was perceived and who would speak it because of social changes.

- RP (Received pronunciation) vs POSH ENGLISH (about 23 min.) – Explains the origins and evolution of RP and the differences between standard received pronunciation (RP) and the more high-class or “posh” version that the upper classes would speak and how regional accents influence even RP. It also explains that, although this accent was known for being used by radio broadcasters, during WWII, radio broadcasters started using more regional accents to make it clear that they were authentic British people because Germans broadcasting propaganda were speaking English with an RP accent. This is one of the factors influencing changes in professional and social views about different types of British accents.

Why does all of this stuff about accents matter? It comes back to social class and education, both of which influence people’s prospects in life. A person’s accent, particularly during the mid-20th century and earlier times, reveals their background and the type of level of education they have. (Less so in the 21st century, after the influences of mass media – tv and the Internet – which enable people to hear more accents than they encounter in person in daily life, changes to the education system, and changing cultural attitudes.) Schools of the time knew that and would make sure that their students could speak in a way that would make them sound as educated at possible. A person who sounded as educated as they said they were would sound more skilled and competent to potential employers, enabling them to get “white collar” jobs, involving more clerical or specialized skills rather than manual labor, and rise up in the middle class. People who only had the the minimal level of education, like Liz’s relatives, wouldn’t have this influence on their speech, and that could be a barrier to finding better jobs, keeping them at a lower, working class level.

Liz and her friends have been learning some RP in school, which is why they can speak more “posh” than the general cockney spoken around them in daily life, but the Breretons speak a higher level of RP because of their boarding school backgrounds and college educations, so even Liz’s more educated version of English isn’t up to their level of RP. Liz and her friends are learning to speak at a middle class level because they’re being prepared for possible white collar jobs and middle-class living. The students’ cockney families speak like the working classes because that’s what they are, and they’re less likely to move up in the world because listeners can tell that they don’t speak in an educated way. The Breretons speak like academics because that’s what they are, that’s what they’ve trained to be, they’ve had higher-class education, and they’re relatively upper-class or upper-middle class. Although the girls’ families think that the girls are learning to speak “posh”, and they are when compared to their relatives, the Breretons can still hear their background in their speech and know they’re not from the same class. This ability to almost diagnose someone’s background and education from a person’s accent influences the way people in the story and society of the time would think of each other right from their first meeting. Because they can tell some significant factors of a person’s background immediately, there was a tendency to jump to conclusions about a persons’ life, habits, and capabilities. Part of this story is about how they assumed too much before getting to know the details of other people’s lives and personalities, and that’s a factor that influenced social attitudes before and after the war. As the videos that I’ve referenced explain, the modern, 21st century versions of the dialects and accents in this story wouldn’t be quite the same as the ones the characters would have spoken in the 1930s/1940s because language evolves over time, but the videos will give you a sense of how the characters hear each other.

When Liz tells Lady Brereton that her father was a Communist, Lady Brereton is intrigued and fascinated but not overly shocked or disparaging. Liz is happy that Lady Brereton appreciates that he was a good and loving father and that Liz badly misses him even if his political views were unorthodox. Today, Britain is more of a democratic socialist nation than the United States, and the social programs of WWII, like the child evacuations, are part of the reason. Britain was a country that was very focused on social class, and before the war, the social classes seldom mixed. However, the war was a nationwide effort. People of all social classes were expected to do their part and work together, and programs like the child evacuations brought people of different social classes together in ways they had never been before. The result was that people of different social classes learned more about the ways other people lived, and because the evacuation system saved many lives and led to improvements in living conditions for some children from poor areas of the city, people in Britain became more interested in social programs to help the poor and create a more stable society. This isn’t the only reason for such social programs, but it was a contributing factor.

In the book, when Liz looks back on her father’s political views, she realizes that she shares some feelings with him but wouldn’t agree on everything he used to say, and that’s because of her own experiences. The social programs of the war helped her to continue her education and find a more stable life than the one she had with her aunt, but she also knows that she can’t rely on that type of support for everything and starts to look for ways that she can earn money herself and live an independent life. Her experience with and approach to social programs seems like a broader, more blended view. She has had experience with different social classes and different systems and can see the benefits and downsides of different ways of living.

For more information about the conditions and experiences of child evacuees, I recommend the following videos:

Evacuees of the Second World War: Stories of children sent away from home

From Imperial War Museums, a series of interviews with former child evacuees with background information. 10 minutes long.

This series of interviews with former child evacuees is much longer than the other one, about 40 minutes long. Part of this one brings up the subject of racial minority children who were evacuated. Children of different racial backgrounds or ones who looked like they might be could be discriminated against by people who were reluctant to host them because of the way they looked, but there were also some nice families who were willing to host them.

An hour-long documentary about evacuees’ experiences, good and bad, with interviews with individual evacuees as older adults. It includes the experiences of evacuees who were sent overseas and not just to the countryside. It also covers the effects that the experience had on their education and how they found it difficult to relate to certain types of lessons, like poetry lessons, because the themes were so far from their wartime lives. It also explains what happened to them after the war was over and the long-term effects that their experiences had on t hem.

What Living In London Was Like During The Blitz

Explains what conditions were like for those who remained in London during the war and what the evacuees were escaping. Timeline Documentary. About 50 minutes.

For other children’s books about WWII and child evacuees, I have a list of WWII books with additional resources. For books about child evacuees, I especially recommend Carrie’s War (1973) and All The Children Were Sent Away (1976).

Education and Children

A detail that I particularly liked about this book was the explanation of the the 1940s British school system at the beginning of the book. I’ve seen other explanations of the British school system online (like this one from Anglophenia on YouTube), but the explanation in this book does help because the main character’s education and future prospects are a major part of the story.

The attitudes about class and education surprisingly still resonate today. The type of education a child receives is often determined by the economic level of their parents and the type of life that the adults expect that the child will lead. All of the parents in the story have their own notions about what the young people should be doing with their lives, but the young people know that the world is changing, especially because of the onset of war. The things they want to do and the things they will have to do no longer match their elders’ expectations.

Liz knows that getting a good education is vital to her future, where she will have to make a living by herself, even though her aunt tries to shame her for being grand about her education and tries to make her feel like she should just go out and get a job like her kids did. The Breretons are just the opposite, seeing higher education as the only path to a secure future, while their sons realize that there are more immediate problems shaping their world and posing real threats to all of their lives. Each of the young people come to realize that there are decisions that they each need to make for themselves to take charge of their lives and handle what life has given them, even if the adults don’t understand.

Overall levels of education in society have risen in the decades since World War II. Technically, where I live, children are only legally required to attend school through 8th grade, but in actual practice, almost everyone gets at least a high school education because even the lowest levels of jobs in our society expect a high school level of education or an employee who is working toward one. There is very little that anyone can do with only an 8th grade education in the 21st century, and almost everything that provides a living wage requires either a college degree or some kind of vocational training beyond high school. There are almost no jobs that will take a person with a minimal level of education and no prior experience.

In 1940s England, there were more opportunities for people with little education to get jobs, which is how Liz’s cousins get jobs even though they leave school at about age 14, but even then, there aren’t many opportunities for jobs that pay well and little opportunity for advancement. Rose later has problems when she gets pregnant as an unmarried teenager, and her cruel mother throws her out of the house, into the bombed streets of London with no way to make her living. Liz and the Breretons help her, but they worry about her future prospects. She has little education and has worked in a shoe store, but she doesn’t know much else and has no other experience. Without an education or other means of support, there isn’t much else she can do. She doesn’t even have very many domestic skills and can’t sew or knit. The end of the book implies that Rose will learn to manage because she decides that she is determined to keep her baby and find a way to support them both, learning whatever she has to learn along the way, and Liz’s teacher, Miss Garnett, will also help her.

Liz loves her cousin enough to take some risks to reach her during the bombings of London and bring her to Chiddingford, but she comes to realize that she has underrated her cousin for being less educated and a bit foolish in her life choices. On the one hand, she is irritated with Rose for her foolish love affair with a man who doesn’t really seem to care about her and marries someone else instead. She and Ben face some real dangers going to London to find her and get her out of the terrible situation she’s in, so a foolish choice on her part does create some risks and hardships for others. However, she finds out that Rose understands some things about life and human relationships that Liz is just now beginning to understand. The reason why she had that love affair was that she felt emotionally neglected by her hard-hearted mother and desperately lonely after Liz left for the countryside. Her choice of lover turned out to be a bad decision, but she was so starved for companionship and affection that she was vulnerable. Part of the reason why Rose is now determined to keep her baby and not place it out for adoption is because she saw the awful way her mother treated Liz as an orphaned child and how badly Liz was starved for affection. Rose’s mother was cruel to her as well, but much more cruel to Liz because Liz wasn’t her own child. Rose wants her own child to know what it is to be genuinely loved and wanted, in spite of the hardships and stigma of being a single, unmarried parent in the 1940s. Liz is touched that Rose truly understands that important emotional need just to feel loved and wanted by someone, something Rose’s mother never seemed to understand or care about. Rose might turn out to be a better parent than her own mother.

The feeling of not being wanted and only reluctantly accepted was one that real-life evacuees experienced, and I thought that was well-represented in the book. When Liz first meets Mrs. Brereton, she reminds her of her aunt. She puts her own children first and is so absorbed with what she thinks are in her family’s best interests that she sees Liz as an inconvenience and possible threat instead of the vulnerable girl she really is. However, where Liz’s aunt never warmed up to her after they lived together for years, Mrs. Brereton does become fond of Liz and starts to think of her as part of the family. With her elder sons going off to war, she admits that it’s a comfort to her to have Liz there. Liz shares in the family’s ups and downs through the war and really becomes one of them. Her attitude contrasts with Liz’s aunt, who is self-absorbed and ready to abandon any of the children in the family, including her own, when they become too much of an inconvenience to her. Mrs. Brereton is different. There are times when she is disappointed or worried by decisions her sons make, but they’re still her sons. Once she starts thinking of Liz as one of the family, she extends the same loyal affection to her. She worries about Liz when she disappears for a time instead of being relieved that she’s gone, and she even takes in her cousin when Liz brings her from London.

It’s hard to say how much of the differences because Liz’s aunt and Mrs. Brereton are due to their relative social positions and how much are because they have different personalities. I’m inclined to think that it’s a combination of both. I can see that Liz’s aunt may feel more precarious in life because she’s a poor, working class woman and feels less able to provide for an extra person or someone in a situation that might require some sacrifices, like her orphaned niece or pregnant daughter. However, Liz’s gran, who is part of the same social class, thinks that Rose’s mother has behaved horribly, both for mistreating Liz for years and for sending her pregnant and penniless young daughter out into the streets while the city is being actively bombed, so it seems that not everyone in that social group would have the same reactions to these situations, and some might be willing to make more sacrifices to help someone in desperate circumstances.

There are themes all through the story about the human need for affection and relationships with other people. Partly, the ability to build relationships with others is recognizing the need for them and being open to building relationships. Mrs. Brereton isn’t really open to building a relationship with Liz at first, and Liz and the Breretons don’t really understand one another, but relationships are also built through shared experiences. Not all of the experiences that the characters in the story share are positive ones, but facing difficult situations together can also be a bonding experience. Mrs. Brereton bonds with Liz and Rose because, even though it’s difficult for her at first, she comes to recognize how Liz supports her family in difficult circumstances, and she’s willing and able to help them through difficult circumstances in return, as a family. Liz’s aunt loses her relationship with both girls because she never develops that appreciation for them or willingness to share in their lives and troubles.

War

The war is always around the characters, and the story is shaped by it. I thought the author did a good job of representing the early events of WWII and how characters would have reacted to them as they actually happened. Each of the young people in particular wants to actively participate in the events that are shaping their world, even though Mr. and Mrs. Brereton would prefer to keep their sons out of it.

The grandfather of the Brereton family understands how the young people feel, having once been a soldier himself. Ben and his grandfather are very much alike, noble-minded and eager to participate. Liz joins Ben and Sir Rollo when they take Sir Rollo’s boat to participate in the Dunkirk Evacuation as one of the “Little Ships.” They know that British soldiers need help returning to England, and they hope to rescue Simon, who has joined the army, and others like him. They end up leaving Liz behind at Ramsgate because they decide that it would be too dangerous to take her the rest of the way with them. Sir Rollo is in bad health and probably shouldn’t be undertaking such a long-shot mission, but family love and his desire to once again be in the thick of things, making a difference, override any thoughts for safety. In the end, he helps save many people, and because of his prior experience in war, he is able to teach Ben how to avoid the floating mines and sandbars in their way.

However, he doesn’t survive the mission himself. He is killed by enemy fire, but Lady Brereton reveals that he knew he was ill and dying anyway. One of the pen-and-ink pictures in the book is actually of Sir Rollo after he got shot, and I was a little surprised that the book would show a blood-stained dead body in that way. It’s not overly graphic, even in the illustration, and because it’s a black-and-white drawing, it’s a less alarming than seeing someone with a red blood stain. Still, I think sensitive readers should be aware that it’s there. The book doesn’t sugarcoat the nature of war at all.

Lady Brereton knew her husband very well and loved his noble qualities. Although he didn’t tell her ahead of time what he and Ben were planning to do, she suspected that he was going to attempt something of that sort. He was a veteran of the First World War, and he wanted his last act to be something heroic, to feel like he made a difference again before he died. Ben is injured during the mission, but he and his grandfather still manage to save many soldiers. It’s Ben’s first view of war directly, and although it was a terrifying experience, it doesn’t change his mind about wanting to join the RAF. His parents finally agree to let him enlist after he finishes his school exams that summer.

At the time the book ends, none of the young people are killed in the war. We don’t know what’s going to happen to all of them by the time the war is over because the story ends in early 1941, but their experiences have made them all realize what’s important to them and given them the determination to do their part in the war effort. The overall situation by the time the book ends is that Britain is feeling like it’s largely fighting the war alone because France has fallen to Germany and is now occupied, and while Britain is getting some supplies from the US, the US would not fully enter the war until the attack of Pearl Harbor in December 1941. For a more detailed explanation of the war situation in Britain in 1940, I recommend the Timeline documentary 1940: When Britain Stood Alone In WW2 on YouTube. Understanding the general course of events in context adds depth to the story.

Toward the end of the book, there seems to be a romance developing between Liz and Ben. Personally, I like to imagine that Liz and Ben might marry after the war. I’d like to imagine, too, that Rose might end up marrying Simon and have a comfortable life as a doctor’s wife after the war. That’s left to the imagination, though.

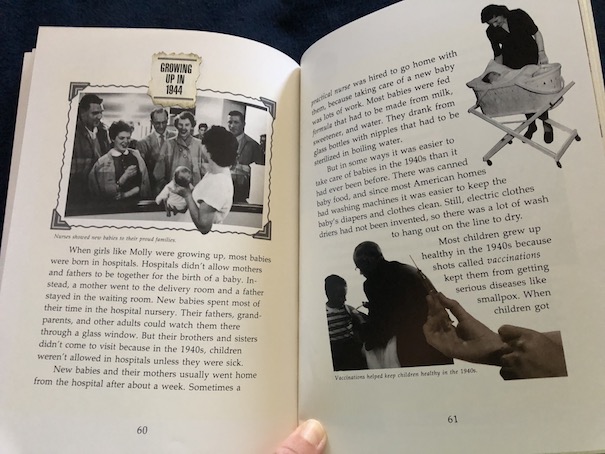

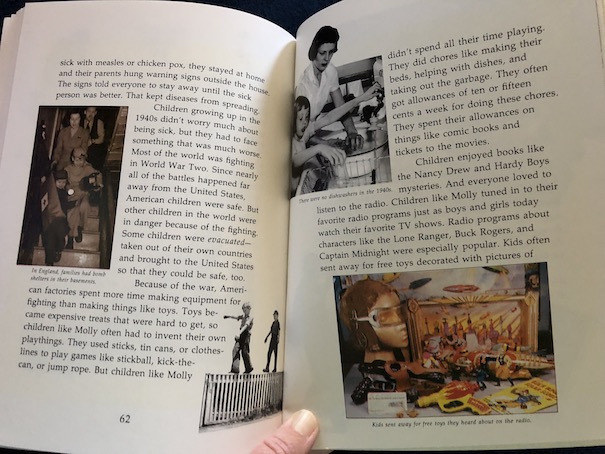

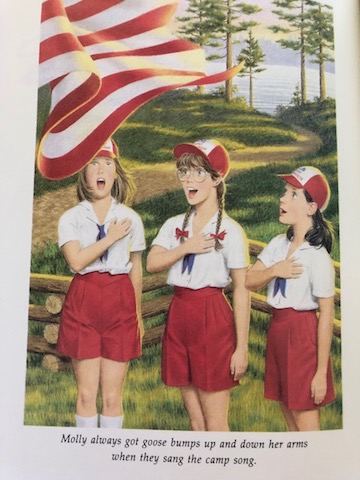

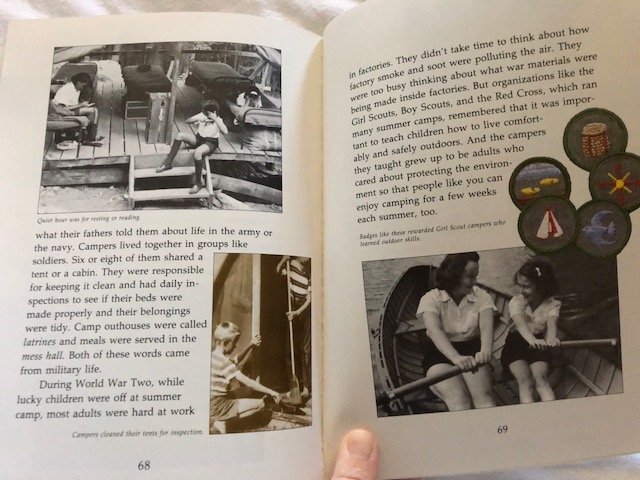

Molly and her friends, Linda and Susan, are attending Camp Gowonagin over the summer. They love summer camp because there are so many fun things to do, like nature hikes, archery, arts and crafts, and campfire sing alongs. The only thing Molly doesn’t like is swimming underwater, although she’s embarrassed to admit it. Susan has trouble with canoeing because she doesn’t know how to keep her canoe moving straight. Other than that, all three girls have fun at camp and as their time at camp is coming to an end, they think about how much they’ll miss it.

Molly and her friends, Linda and Susan, are attending Camp Gowonagin over the summer. They love summer camp because there are so many fun things to do, like nature hikes, archery, arts and crafts, and campfire sing alongs. The only thing Molly doesn’t like is swimming underwater, although she’s embarrassed to admit it. Susan has trouble with canoeing because she doesn’t know how to keep her canoe moving straight. Other than that, all three girls have fun at camp and as their time at camp is coming to an end, they think about how much they’ll miss it. Molly and Susan end up on the Blue Team, while Linda is assigned to the Red Team. Molly and Susan aren’t really looking forward to the Color War because their team captain will be Dorinda, a bossy, competitive girl who likes to act like she’s the general of an army and this camp game is a real war. Molly is uneasy about what Dorinda will order them to do, afraid that it might involve the thing she dreads most, swimming underwater. The only comfort Molly takes is what her father told her before he went away to war, that being scared is okay because it gives a person a chance to be brave.

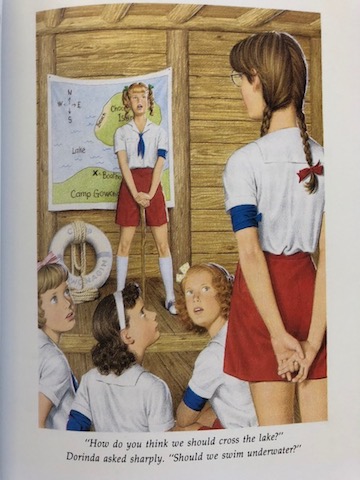

Molly and Susan end up on the Blue Team, while Linda is assigned to the Red Team. Molly and Susan aren’t really looking forward to the Color War because their team captain will be Dorinda, a bossy, competitive girl who likes to act like she’s the general of an army and this camp game is a real war. Molly is uneasy about what Dorinda will order them to do, afraid that it might involve the thing she dreads most, swimming underwater. The only comfort Molly takes is what her father told her before he went away to war, that being scared is okay because it gives a person a chance to be brave. Of course, Dorinda’s plan doesn’t work out as she thought. The Red Team’s scout spots them right away and takes most of the Blue Team prisoner. Only Molly and Susan are left free because Susan accidentally overturned their canoe on the way to the island. After they manage to get back into their canoe and bail it out, they try to approach the beach, but Linda spots them and signals to the rest of the Red Team. Molly and Susan have no choice but to return to camp to avoid capture.

Of course, Dorinda’s plan doesn’t work out as she thought. The Red Team’s scout spots them right away and takes most of the Blue Team prisoner. Only Molly and Susan are left free because Susan accidentally overturned their canoe on the way to the island. After they manage to get back into their canoe and bail it out, they try to approach the beach, but Linda spots them and signals to the rest of the Red Team. Molly and Susan have no choice but to return to camp to avoid capture. Molly and Susan (and the rest of the Blue Team, once they’re free) manage to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat, but they worry that perhaps their friendship with Linda is ruined because of the trick they play on her. Fortunately, Linda decides to take it in the spirit of the game and shows sympathy for the girls when it turns out that their victory plan ends with the entire Blue Team getting poison ivy.

Molly and Susan (and the rest of the Blue Team, once they’re free) manage to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat, but they worry that perhaps their friendship with Linda is ruined because of the trick they play on her. Fortunately, Linda decides to take it in the spirit of the game and shows sympathy for the girls when it turns out that their victory plan ends with the entire Blue Team getting poison ivy.

Molly McIntire misses her father, who is a doctor stationed in England during World War II. Things haven’t been the same in her family since he left. Treats are more rare because of the sugar rationing, and she now has to eat yucky vegetables from her family’s victory garden all the time, under the watchful eyes of the family’s housekeeper. Her mother, while generally understanding, is frequently occupied with her work with the Red Cross. Molly’s older sister, Jill, tries to act grown-up, and Molly thinks that her brothers are pests, especially Ricky, who is fond of teasing. However, when Molly and her friends tease Ricky about his crush on a friend of Jill’s, it touches off a war of practical jokes in their house.

Molly McIntire misses her father, who is a doctor stationed in England during World War II. Things haven’t been the same in her family since he left. Treats are more rare because of the sugar rationing, and she now has to eat yucky vegetables from her family’s victory garden all the time, under the watchful eyes of the family’s housekeeper. Her mother, while generally understanding, is frequently occupied with her work with the Red Cross. Molly’s older sister, Jill, tries to act grown-up, and Molly thinks that her brothers are pests, especially Ricky, who is fond of teasing. However, when Molly and her friends tease Ricky about his crush on a friend of Jill’s, it touches off a war of practical jokes in their house. Halloween is coming, and she wants to come up with great costume ideas for herself and her two best friends, Linda and Susan. Her first thought is that she’d like to be Cinderella, but her friends are understandably reluctant to be the “ugly” stepsisters, and Molly has to admit that she wouldn’t really like that role, either. Also, Molly doesn’t have a fancy dress, and her mother is too busy to make one and also doesn’t think that they should waste rationed cloth on costumes. Instead, she suggests that the girls make grass skirts out of paper and go as hula dancers. The girls like the idea, but Halloween doesn’t go as planned.

Halloween is coming, and she wants to come up with great costume ideas for herself and her two best friends, Linda and Susan. Her first thought is that she’d like to be Cinderella, but her friends are understandably reluctant to be the “ugly” stepsisters, and Molly has to admit that she wouldn’t really like that role, either. Also, Molly doesn’t have a fancy dress, and her mother is too busy to make one and also doesn’t think that they should waste rationed cloth on costumes. Instead, she suggests that the girls make grass skirts out of paper and go as hula dancers. The girls like the idea, but Halloween doesn’t go as planned. Because he laughed at the girls, saying that he could see their underwear after he sprayed them with water and ruined their skirts, the girls decide to play a trick that will give Ricky his just desserts. The next time that Jill’s friend comes to visit, the girls arrange to have Jill and her friend standing underneath Ricky’s bedroom window when they start throwing all of his underwear out the window, right in front of Ricky. Ricky screams at the girls that “this is war!” just as their mother arrives home.

Because he laughed at the girls, saying that he could see their underwear after he sprayed them with water and ruined their skirts, the girls decide to play a trick that will give Ricky his just desserts. The next time that Jill’s friend comes to visit, the girls arrange to have Jill and her friend standing underneath Ricky’s bedroom window when they start throwing all of his underwear out the window, right in front of Ricky. Ricky screams at the girls that “this is war!” just as their mother arrives home.

This is part of the

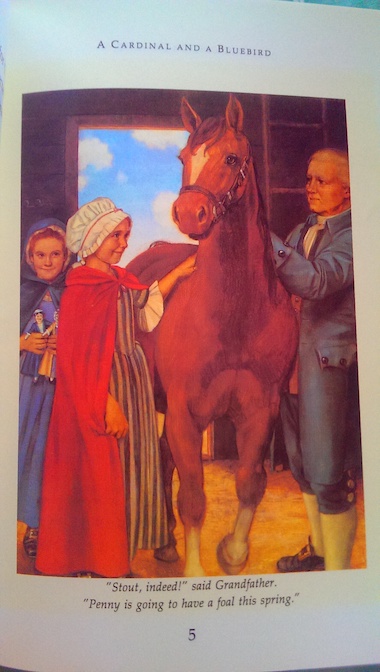

This is part of the  Unfortunately, Elizabeth’s father also soon ends up in prison. Tensions between Patriots and Loyalists are high. The former governor has fled Williamsburg, and Patriots are arresting Loyalists. That Mr. Cole is a Loyalist has been well-known for some time. Felicity fears for Elizabeth and wonders what will happen to their friendship.

Unfortunately, Elizabeth’s father also soon ends up in prison. Tensions between Patriots and Loyalists are high. The former governor has fled Williamsburg, and Patriots are arresting Loyalists. That Mr. Cole is a Loyalist has been well-known for some time. Felicity fears for Elizabeth and wonders what will happen to their friendship. With the war everyone has dreaded finally becoming reality, there are still more changes yet to come. Elizabeth’s father must leave Williamsburg, Felicity’s father decides how he will support the war effort, and Felicity begins to play more of a role in the running of her father’s shop, as she had wished to do before.

With the war everyone has dreaded finally becoming reality, there are still more changes yet to come. Elizabeth’s father must leave Williamsburg, Felicity’s father decides how he will support the war effort, and Felicity begins to play more of a role in the running of her father’s shop, as she had wished to do before.