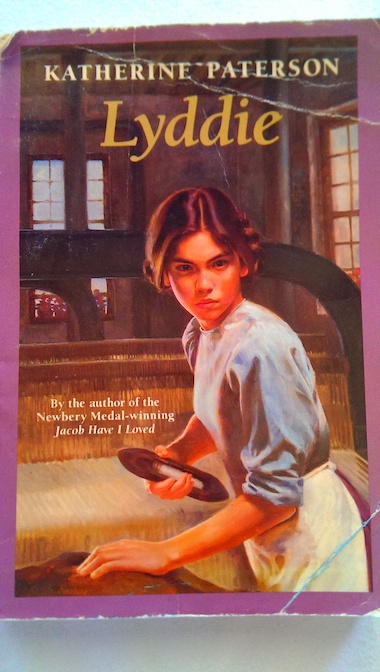

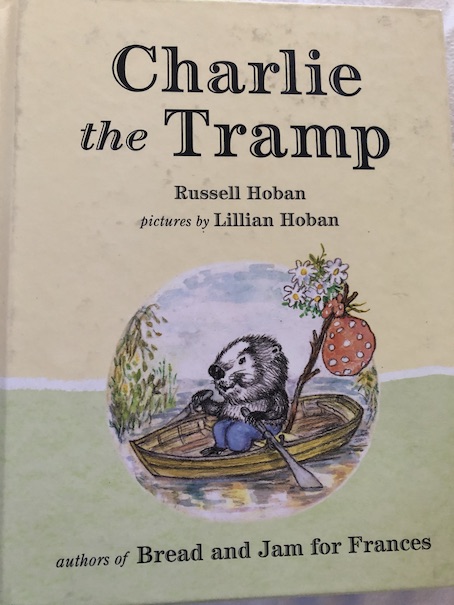

Charlie the Tramp by Russell Hoban, illustrated by Lillian Hoban, 1966.

Disclosure: I am using a newer edition of the book, published by Plough Publishing House. Plough sent a copy to me for review purposes, but the opinions in the review are my own.

One day, when Charlie Beaver’s grandfather comes to visit, his grandfather asks him what he wants to be when he grows up. The grandfather assumes that he knows the answer to the question because everyone in the family is a beaver, and beavers naturally do beaver work. (Beaver is apparently both species and profession in books where beavers talk and wear clothes.) However, Charlie stuns his family when he declares that he wants to be a tramp.

Few families would be happy to hear a child say that he wants to be a tramp. Charlie’s grandfather says that he’s never heard a child want to be tramp, and his mother says that she doesn’t think he means it. However, Charlie thinks that being a tramp would be good because he wouldn’t have to learn how to chop trees or build dams or other routine jobs. Charlie thinks that tramps have a lot of fun and just work now and then at little jobs when they need something to eat. Charlie thinks that the little jobs would be much more fun than the ones his father really wants him to do. Charlie’s grandfather says that kids these days just don’t want to work hard.

However, Charlie’s parents decide that if he wants to be a tramp, they’ll let him try it out. Charlie makes himself a little bundle with some food, and his parents let him sleep outside, telling him to come back for breakfast. Both the father and grandfather quietly admit that they both wanted to be a tramp when they were his age, so it’s not just kids these days.

Charlie has some fun, roaming the countryside, sleeping under the stars, and enjoying his freedom. In the morning, he comes home and does some chores to earn his breakfast, lunch, and dinner. In between, he goes out to roam the countryside again.

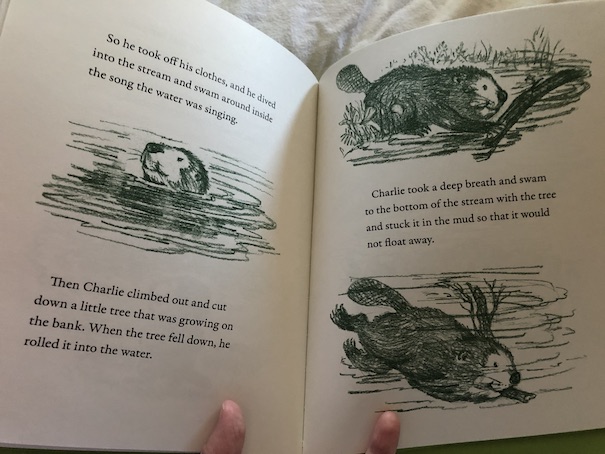

Charlie begins to notice that something keeps waking him up in the night, an odd sound that he can’t identify at first. Eventually, he realizes that it’s the sound of a nearby stream. For some reason, the trickling sound of the stream seems nice but makes him feel restless. It inspires him to swim in the stream and begin building his own dam, working through the night.

When Charlie sleeps through breakfast, his family comes looking for him and admires the good job that Charlie did on his dam and the pond that he has created. When they ask him about why he was making a dam when he was trying to be a tramp, Charlie says that he likes doing both and can do either sometimes. His family is satisfied that Charlie is a good worker, and his grandfather says, “That’s how it is nowadays. You never know when a tramp will turn out to be a beaver.”

It isn’t that Charlie expects to go through life without doing work because he insisted on working to earn his meals even when he was being a tramp. It was more that Charlie wanted the freedom to decide when he wanted to work and what kind of work he was going to do. However, he is a beaver and has a beaver’s instincts. In the end, he sees the appeal of doing a beaver’s work, building dams, enjoying it because he made the dam himself in the way he wanted to make it. I think it shows that when a person has the knowledge and ability to do something and the interest in doing it, they will eventually use their skills, perhaps in surprising ways. I remember reading some advice to writers that said that people write because “they can’t not do it,” and that’s true of many aspirations in life. Sometimes, when people know what they really want to do with their lives, they can’t resist doing it, and sometimes, people realize what their aspirations are when they find something that they can’t resist doing. Charlie is a beaver because it’s a part of who he is, and he can’t not do it. As he grows up, he will continue growing into that role, just as human children eventually grow up to be the people they are going to be.

This book is available to borrow for free online through Internet Archive, but it’s also back in print and available for purchase through Plough. If you borrow the book and like it, consider buying a copy of your own!