Mary Poppins by P. L. Travers, 1934.

This book is a classic piece of children’s literature! This is the first book in a series of about the adventures of the Banks children with their magical nanny, Mary Poppins.

Mr. and Mrs. Banks of Cherry-Tree Lane have four children: Jane, Michael, and the infant twins, John and Barbara. When the story begins, the children’s nanny has just suddenly left her job with no real explanation. Mrs. Banks is beside herself, wondering what to do about this household upheaval, and Mr. Banks offers the practical suggestion that she should advertise for a new nanny in the newspaper. Mrs. Banks decides that’s a good idea, but a strange wind from the East brings an unexpected answer to this domestic problem.

When Mary Poppins arrives at the Banks’ house to take the position of nanny, it seems like she was blown there by the wind. When the children ask her, she says that’s indeed what happened, but she offers no other explanation. Mrs. Banks discusses the position of nanny with her, but it turns out that it’s more like Mary Poppins is interviewing her and evaluating the children to see if they’ll do. Mary Poppins refuses to provide references when Mrs. Banks asks for them (I would find that worrying), saying that people don’t do that anymore because it’s too old-fashioned. Mrs. Banks actually buys that explanation and doesn’t want to seem old-fashioned, so she stops asking. Mary Poppins basically grants herself the position of nanny as if she were doing the Banks’ family a favor. Maybe she is.

Jane and Michael can tell right away that Mary Poppins is no ordinary nanny. When she begins unpacking her belongings, it seems at first that her carpet bag is empty, but she soon starts pulling many different things out of it, including some things that should be too big to be in the bag at all. Then, she gives the children some “medicine” (she doesn’t say what kind of medicine it is or what it’s supposed to do) that magically tastes like everyone’s favorite flavor.

From there, the story is episodic. Each chapter is like its own short story.

On her day off, Mary Poppins meets up with the Match Man called Bert, who also paints chalk pictures, and when he doesn’t have enough money to take her to tea, they jump into one of his chalk paintings and have a lovely tea there. The children aren’t present for that adventure, but they do go to tea at Mary’s uncle’s house.

Mary’s uncle, Mr. Wigg, is a jolly man … maybe a little too jolly. It’s his birthday, which has filled him full of high spirits, and he literally can’t keep his feet on the ground. When they arrive, he’s hovering in the air. He says that it’s because he’s filled up with Laughing Gas because he finds so many things funny. It’s happened to him before, and he can’t get down to earth again until he thinks of something very serious. The whole situation is so funny that Jane and Michael begin to laugh and find themselves floating in the air, too. Even though Mary isn’t amused and doesn’t laugh, she makes herself float in the air also and bring up the tea table so they can all have their tea in midair. The merriment only ends when Mary Poppins finally tells the children that it’s time to go home, which is very serious indeed.

Mary Poppins understands what animals are saying, helping to sort out matters for a pampered and over-protected little dog who desperately wants a friend to come live with him. Then, when the children see a cow walking down their street, Mary Poppins says that cow is a personal friend of her mother’s and is looking for a falling star. On Mary Poppins’s birthday, she and the children attend a bizarre party in the zoo where the animals are their hosts.

There is an episode in the book which has some uncomfortable racial portrayals. It takes place when Mary Poppins shows the children how a magical compass can take them to different places around the world, and they meet people who are basically caricatures of different racial groups. (This episode has resulted in the book being banned by some libraries. P. L. Travers received complaints about it in her lifetime, and she revised the scene in later printings of the book, which is why you’ll see books labeled as “Revised Edition.” I have more to say about this scene, but I’ll save it for my reaction.)

Mary Poppins and the children visit a bizarre shop where the owner’s fingers are candy and grow back after she breaks them off and gives them to the children. (That’s actually pretty freaky.) The children save the gold paper stars from the gingerbread they buy at the shop, and later, they see Mary Poppins and the shop owner and her daughters putting the stars up in the sky.

There is a story about the babies, John and Barbara, and how they understand things that the adults and older children don’t, like what animals, the wind, and sunshine are saying. They are sad to learn that they will forget these things as they grow up.

Toward the end of the book, Mary Poppins takes the children Christmas shopping, and they meet Maia, one of the Pleiades (here she is considered to be a star as well as a mythological figure, and she looks like a young, scantily-clad girl), who has come to Earth to do her Christmas shopping as well.

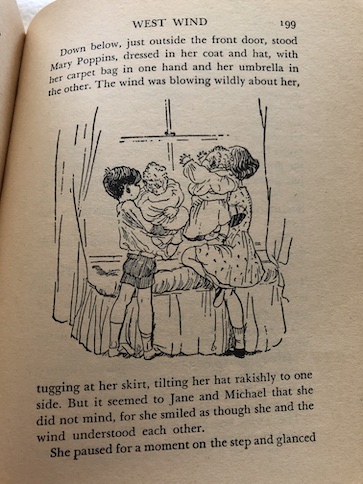

In the end, Mary Poppins leaves the Banks family suddenly when the wind changes directions, flying off into the sky on the wind with her umbrella. She does not say goodbye, and the children are very upset. Mrs. Banks is angry with Mary Poppins for her sudden departure on a night when she was counting on her to be there to take care of the children. The children try to defend her, though, and say that they really want her back, even though she’s often cross with them. However, she does leave behind presents for the children that hint that she may come back someday.

The book is available to borrow and read for free online through Internet Archive (multiple copies).

My Reaction

In some ways, the Mary Poppins in the original books isn’t quite as pleasant as Julie Andrews in the Disney movie version. The Mary Poppins in the book is vain and stuck up. She can be intimidating in her manner, refuses to answer questions, and even gets rude and snippy with the children. She was a little like that in the movie, but in the book, she’s even more so. After any strange or magical thing happens and the children want to talk about it, Mary Poppins gets angry at them and denies that any such thing happened at all. I found that rather annoying because it’s kind of like gaslighting, denying things happened when they really did happen. I think we’re meant to assume that’s because the adults aren’t allowed to find out that magical things have happened because they might put a stop to it or because Mary Poppins realizes that the children can only enjoy this kind of magic for a brief phase of their lives and that they’ll have to grow up in the more mundane world, just like the little twins can’t help but lose their ability to talk to animals. It’s a little sad, but I think it’s meant to provide some kind of rational explanation about how magic can exist in the world but yet go unnoticed by most people.

There is a Timeline documentary that discusses the life of P. L. Travers and how she felt about the Disney movie version of Mary Poppins. Although many people came to know and love the character through the Disney movie, and it made the books much more popular, P. L. Travers thought that the animated portions were silly and the characters weren’t represented as she wrote them.

I’d like to talk more about the racially-problematic episodes with the magic compass. A compass that can take people to different areas of the world just for asking is a good idea, but the people they meet in the places they go are all uncomfortable caricatures of different races. The one part that I’m not really sure about is how seriously these were meant. When I was trying to decide what to say about this, I considered the idea that aspects of this part of the story may have been meant as a parody of things from other children’s books and popular culture at the time. I have seen even older vintage children’s books that poke fun at concepts from earlier stories, so it occurred to me that this book might be making fun of concepts about people from around the world that young children of the time might have from things they’ve read in other books. There is a kind of humor throughout the book that involves puns and plays on certain ideas, like the way her uncle insists that he floats when he’s in a humorous mood because he’s buoyed up by “Laughing Gas”, which is not what real “Laughing Gas” is. It’s like what a child might picture as “Laughing Gas”, if they didn’t already know what that term means. It’s possible that part of this scene might be parodying other children’s fantasy books about magical travel, but it’s still very uncomfortable to read the original version of this scene, if you don’t have one of the revised editions of the book.

On the other hand, I suspect that the author isn’t really that thoughtful or self-aware by the way the adult characters speak throughout the book series. At the end of the book, when Michael is upset at Mary Poppins suddenly leaving and he throws a fit and argues with her, his mother tells him not to act like a “Red Indian.” I’m not entirely clear on what that comment was supposed to mean in that context, but Mrs. Banks uses it as if she does, so it seems that there is some implied insult there, maybe equating Michael’s behavior to being “savage” or “uncivilized” or something of that nature. Even Mary Poppins herself uses racial language throughout the series, using words like “hottentot” or “blackamoor” to criticize the children when they misbehave. It makes me think that the author was accustomed to that kind of talk herself. If Mary Poppins can get snooty as a character, I think I have the right to express my disapproval of her behavior as well.

While I like the basic character of a magical nanny who takes children on magical adventures, I don’t like either those comments or the compass scenes because the obvious caricatures are uncomfortable, and I don’t think they make good story material for children. I would recommend saving that version for adults who are interested in reading or studying nostalgic literature and use the revised versions for children, who would probably just prefer to have a story they can enjoy for fun without needing a lesson on racial attitudes of the past to understand it. If they’re curious, they can always have a look at the original later, when they’re old enough to understand it better and put it perspective. In the revised compass scenes in later books, some printings still have people but some of the offensive words removed, and in later printings, the children meet different types of animals instead of people.